How I Spent My Summer Vacation: Hungary and Italy (Again!)

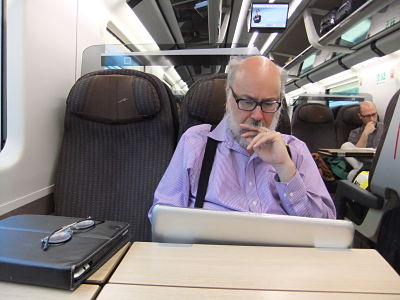

/Budapest, Hungary Cynthia and I had really enjoyed traveling by rail inside many of the countries we visited this trip, so we decided to take the train from the Czech Republic north to Hungary, passing along the way through Slovokia. We alternated between reading and looking out the window as the train click-clacked through farm country, small towns and villages, and lush forests, giving us a much bigger picture of what Eastern Europe looked like once you got outside of the major cities. America has somehow lost its historic relationship with the railroads, but in Europe, people of all classes and backgrounds travel by train, the trains are clean, affordably priced, and comfortable. So, what's not to love.

Around the time we passed into Hungary, something changed though. The temperature outside got hotter and hotter, there was no air conditioning working inside the train, and the windows did not open to allow outside air to circulate. The train was becoming a sweat box and the scaldingly hot temperature (I say scalding because the air was so humid that it felt like we were sitting in boiling water) began to percolate our brains. Needless to say,the experience had cured us of our romance with the rails. By the time the train arrived in Budapest, we were melting into a puddle and in a punch drunk stupor. Then, our host, Ellen Hume, swooped down upon us, with fresh bottles of cold water, with a driver to take our bags and an air conditioned car, like an angel of mercy!

Ellen Hume is probably the most resourceful person I have ever met! She covered the White House for the Wall Street Journal; she ran PBS's Democracy Project, where she became a major advocate for citizen-driven and resource-based journalism; she helped direct Harvard's Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, and she ran a major Boston-based initiative on Ethnic news media. And, for a year and a half, she worked with me as the Research Director for MIT's Center for the Future of Civic Media, a initiative funded by the Knight Foundation, a collaboration between Comparative Media Studies and the MIT Media Lab. Below you see Ellen and I together on the grounds of the Buda Castle.

Budapest, Hungary's capital and largest city, was historically two cities named, predictably, Buda and Pest, which are separated from each other by the Danube River (as you can see fairly well in the photograph below). When we arrived, we dropped our bags off at our hotel, which was near the river on the Pest side, and then walked across the bridge to visit the historic center of Buda.

Our experience of Buda was dominated by the Buda Castle, built in 1265, and long the home of the Hungarian Kings and Emperiors, and the Castle Hill. The architecture of this area, as the image below suggests, is commanding, giving us just a taste of what life might have been like during the hayday of the Austria-Hungarian Empire.

The closer you get to the Castle proper, the more you get a taste of Medieval Hungary . It was too late in the day to get inside the buildings, but we wandered the grounds, enjoying the sight of this falconer in traditional garb and especially the view looking out across the Danube, a vista which gave us a clear sense of why this location was originally chosen to support a fortress.

A distinctive feature of Budapest's architectural tradition are the brightly colored Zsolnay tiles, shown here covering the roof of Matthias Church. The Zsolnay company has manufactured parcelain and ceramic tiles since the early part of the nineteenth century, though it has struggled to hang on during the current economic crisis in Europe.

Budapest became the country's capital in the late 19th century as several local towns were united to create one large urban area. Most of the public buildings were built during this period, and by the early 20th century, Budapest had developed a reputation for being one of the most cosmopolitan areas in Europe. For all of those reasons, the city's look and feel was strongly influenced by a particular inflection of Art Nouveau. These grand old world buildings exist side by side with monstrosities from Stalin- and Khruschev-area Soviet monumentalism, not exactly the most satisfying combination in the world, but a physical reminder of the transformations (political, cultural) which Hungary underwent across the twentieth century.

One of the best bits of advice we received upon launching on our grand European adventures was to "look up!" The most spectacular aspects of Europe often are above eye-level -- especially the decorative details along the roofs and top floors of buildings. We were constantly struck by the distinctive national styles that define each of the European countries, despite, what might seem to us by American standards, as very limited distances between them geographically.

Note, for example, the bee-hives on the building above, a key motif in the architecture of Budapest, which historically stood for all the work going on inside.

And, the same would be true of the ceilings inside buildings, such as the one below from the Hungarian Parliament, which is ornately decorated as a showcase to the wealth and power commanded by Imperial Hungary.

Of course, not all of the decorative details are along the skyline. There is also an attention to style which extends to the sidewalks and public plazas of the city, which often become staging grounds for personal and shared rituals.

We turned one corner and found an entire group of ballroom dancers waltzing inside a fountain which was shooting water up all around them. Did we mention yet how blasting hot it was when we were visiting Budapest?

Ellen took us to visit the Grand Market Hall at Nagyvasarcsarnok. Sometimes described as "a symphony in iron," the building was designed by Gustave Eiffel (of the Eiffel Tower fame). I always enjoy visiting farmer's markets and food halls as I travel because they give us such a strong sense of the everyday lives of the people who live in each place we visit. Here, Ellen and I are admiring a shop dedicated to Paprika, in all of its many manifestations. Paprika is the core spice used in Hungarian cooking. I especially enjoyed Paprika in a bowl of authentic Hungarian goulash. My mother used to prepare goulash when I was a child, but it bore very little relationship to this dish, which was a rich, spicy , bright red soup. I have to say how much we enjoyed our meals in Eastern Europe -- both the roasted meats and dumplings we had in Praha and the soups (hot and cold) we tasted in Budapest .

Ellen and her husband, John Shattuck, took us to a a Ruin Bar. These bars have been springing up over the past ten years or so in the old District VII neighborhood (the old Jewish quarter) in the ruins (hence the name) of abandoned buildings, stores, or lots. The area had been largely left to decay in the aftermath of the Second World War, and it has only recently come alive as the hub for the city's hipster nightlife. The ruin bars, many of which operate without a license, allegedly rely on monetary compensations handed directly to local law enforcement, and feel like something out of a post-appocalyptic science fiction film. Somehow, the Mad Max movies or Escape to New York came to mind, but there is also this distinctive Post-Communist feel that is not really captured by the analogy. The walls are covered with graffiti; the furniture looks like it was picked up off the streets, there are Christmas lights and old computers and rusting bathtubs and plastic gewgaws everywhere you look. There may be a band playing in one of the darker corners, and the whole place is teaming with people of all backgrounds and ages. Ellen had promised us that the ruin bar would be one of the highlights of our trip to Europe, and it certainly was.

Here, you see Ellen, John, and I drinking Unicum, the local drink whose family history was memorialized in the film Sunshine, and Cynthia and I (below) surrounded by the graffiti at Szimpla Kert, which was the original and still the largest of the ruin bars. John was the Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights and Labor under Bill Clinton, where he helped to establish the International Tribunals for Rwanda and the Former Yugoslavia, a former U.S. Ambassador to the Czech Republic, the former CEO for the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation, and the current president of Central European University, which hosted my talks in Budapest.

Central European University operates with a heavy endowment from George Soros, and was designed to be an instrument fostering a greater sense of cultural understanding and appreciation of human rights, a meeting place for students from across Europe, and indeed, from around the world. Its students come from more than a hundred countries, and its faculty represent thirty different nations. I spoke in the morning with the students from their summer program (again, featuring probably the most ethnically and nationally diverse audience I encountered on my trip) and in the afternoon, I gave a public lecture (again, the Content talk) at the Open Society Archives, a research facility dedicated to preserving the records of the Communist era.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vW9750DLJ54

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkeIrH3DA8o&feature=relmfu

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0YkR4qgjAvA&feature=relmfu

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Wbg4FcV4pE&feature=relmfu

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eh5l1k7izmQ&feature=relmfu

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ph7EbCNAICI&feature=relmfu

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LvjQpn9vo-c&feature=relmfu

Ellen and John were nice enough to host a lovely salon and dinner in their home, which brought together a mix of intellectuals, artists, writers, and political leaders, which gave us a great taste of the cultural life of Budapest's intelligentsia. I was especially delighted to reconnect with Tibor Dessewffy, the Hungarian Director for the World Internet Project. I had met Tibor when he was a visiting scholar at the USC Annenberg School, and he provided us with some very helpful critical feedback on our Spreadable Media manuscript.

Each leg of the trip was shaped by the personality of our hosts as much as by the personality of the cities themselves. Our experience of Praha was primary focused around culture, especially the rich heritage of film and the graphic arts. Our experience of Budapest, in part because we were spending time with people who have enormous expertise on foreign policy, was focused much more on the political history of the region, especially on the struggles to define a national identity in the wake of many decades of foreign dominance (by the Nazis and the Communists) and the current struggles to protect free expression under an increasingly repressive regime. Our sense was that Budapest is a city which still struggles with the legacy of the Cold War in ways that Praha seems to have moved beyond, but what do I know, I was only there for a few days.

We were lucky enough to get a guided tour of some of the political landmarks of the city by Jeff Taylor, an American art history professor at SUNY Purchase who is an expert on international art forgery, and who sometimes takes tourists around the city to give them a counter-history to some of the national monuments. You have to love a tour guide who quotes Edward Said in his opening remarks.

Jeff's guide of the Museum of Terror helped to debunk and deconstruct the official accounts of Hungary's experiences with the Nazis and the Soviets, drawing out what was not explicitly stated, filling in what was intentionally occluded, and otherwise, poking fun at the ways history was being mobilized to support the country's current leadership. In particular, the bulk of the museum dealt with the Soviet era with very limited space given to the Nazi period, and little to no mention made of the ways that the Hungarian government had officially partnered with Hitler in the early days of World War II.

Jeff also showed us some key monuments, both those which survive from the era of Soviet dominance, and those which reflect the fall of Communism, as it has been framed from the Hungarian perspective. Here, for example, you see me clowning around at a statue dedicated to Ronald Reagan. Seeking to explain that it was as much American popular culture and consumer goods as it was American foreign policy which contributed to some of the political shifts that impacted his adopted country, Jeff has launched the Two Ronalds project, playfully paying tribute to American president Ronald Reagan and American fast-food brand icon Ronald McDonald, by having guests take their picture next to this statue, once they have inserted a Big Mac into Reagan's open hand.

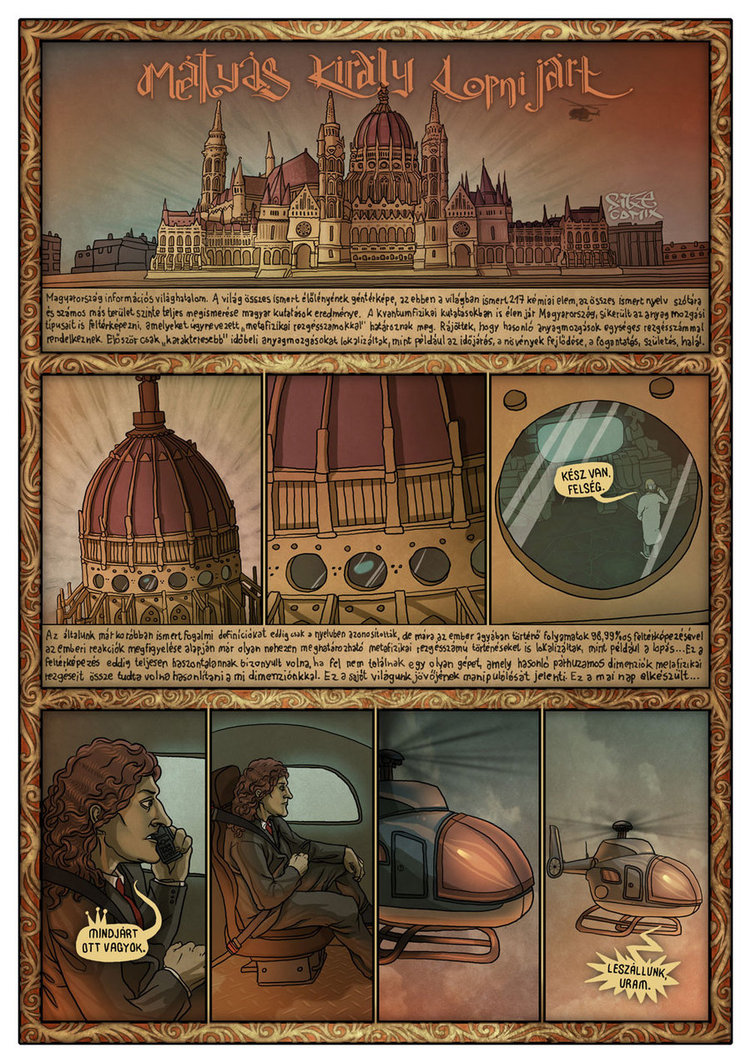

When the good folks at Central European University learned of my strange obsession with understanding the comics cultures of Europe, they tapped their collective networks and got me in touch with Robert Vass, an independent comics artist in Budapest, who took me to his local shop, gave me a guided tour of its contents, and a mini history of comics publishing in Hungary under Communism and its aftermath. I am still absorbing much of what I learned and trying to parse my way through the various comics I purchased, but I have found this Wikipedia entry especially helpful in understanding the local comics scene there. One of my favorite books was Matyas a Kiraly: kepregeny-antologia. Matthias Corvinus was the Renaissance era King of Hungry who has been credited with helping to promote arts, science, and law in his country, and who was later named one of the most important saints in the region. Here, we see his statue outside Matthias Church, which, we saw earlier, was in the Buda Castle region.

During communism, many of the comics published were literary and historical adaptations, which was seen as less "political" than some of the themes that dominated comics elsewhere in Eastern Europe. I am always intrigued how strands in American comics which had largely died out in my country continue to exert influence in other parts of the world, and I've discovered that Hal Foster's Prince Valiant offered a compelling model for many Eastern European comics creators. This collection of contemporary alternative comics drew inspiration from Matthias's story but pushed it in radical new directions, demonstrating that Hungarian comics can be so much more than classics illustrated. Here's a sample page from the collection which I found online. The building depicted here is the Matthias Church.

BOLOGNA, ITALY

My original plan for Bologna was to spend a week sitting in dark theaters and watching beautifully restored prints of great old movies at Il Cinema Ritrovato. Organized by the Cineteca Bologna, this film festival organizes retrospectives intended to deepen our understanding of key figures and chapters in the history of global cinema. For example, among the topics this year, there was an extensive series of films by Lois Weber, perhaps the most important female director of the American silent cinema whose films are deeply shaped by the political and spiritual values of first wave feminism, and by Alma Hitchcock, the wife of Alfred, but also a well known scenario writer in the late silent and early sound British cinema.

The festival also featured a series showing the coming of sound in Japan, which included several films whose soundtrack captured the performances of famous Benshi. In the Japanese tradition, silent films were narrated by live performers, who might recount the story, embody the perspectives of the various characters, direct attention onto key details, or offer their own moral (and sometimes ironic) commentary on the action. These benshi were so popular in their own day that they helped to slow down the coming of sound in Japan, when they resisted the shift to new technologies that might mean their eventual unemployment and the end of their tradition. During this transitional period, some of their performances were recorded, which gives us a chance to better understand their mode of presentation and the diverse ways they shaped spectators' experience of silent Japanese movies.

There was a series of films showing how America and Europe had dealt with the economic crisis of the early 1930s and another showcasing the work of Ivan Pry'ev, who was one of the most popular directors of musicals in the Soviet Union during the Stalinist period (fascinating historical documents which might include celebrations of the heroicism of wives who renounce their husbands for acting against the interests of the State or which might open with vast musical numbers involving farmers singing as they drive their tractors across their fields.)

My favorite screening series, though, was a retrospective of the works of Raoul Walsh, whose career spans from silent films (such as The Thief of Bagdad and The Big Parade) all the way into the 1950s (represented here by Band of Outsiders, Pursued, and Distant Drums). The festival decided, wisely, not to focus on the Walsh films which are perhaps best known to retro house audiences -- his films of the late 1930s and early 1940s with Humphrey Bogart (They Drive By Night, High Sierra), James Cagney (White Heat, The Roaring Twenties), and Errol Flynn (They Died with Their Boots On, Gentleman Jim), but rather to focus primarily on the transition from silent to sound cinema. As a result, I got to see The Big Trail, for example, an epic western which made effective use of deep focus photography to cram every frame with action and details, and was filmed (and shown) in an early wide screen process, Grandeur, Me and My Gal with a wet-behind-the-ears Spencer Tracy and Sailor's Luck which managed to perfectly merge the screwball and anarchistic comedy traditions. Another highlight from the festival for me was Frank Borzage's Man's Castle, also with Spencer Tracy, a dark and twisted romance set amongst the homeless camping out in Central Park during the early depression. Kristin Thompson wrote a typically thoughtful and detailed account of her experiences at this year's festival.

The film festival has become a favorite academic junket, drawing together many of the world's leading film historians, who enjoy hanging out together, watching obscure yet interesting movies, having long conversations over plates of pasta, and grabbing a quick Gellato on the way back to the hotel, before starting the process all over again the following morning.

Bologna has been gaining in recent years on the other great Italian retrospective festival, Pordenone, which is held each year in October, and which showcases almost exclusively works from the early and silent film periods. Bologna has a more diverse program, including silent and sound films from around the world, and has the virtue of falling during the summer, when American academics can get away for a more extended period. So, this year, I had a chance to catch up with old graduate school instructors (Donald Crafton, Kristin Thompson, Susan Olmer, Richard Abel) and classmates (Charlie Keil, Leslie Midkiff-Debauche, Matthew Bernstein, David Pratt) as well as more recent friends who I see in Los Angeles (Janet Bergstrom, Virginia Wright-Wexman, John Huntington).

While in Bologna, I had a chance to sit down in person with Wu Ming 1 (and for part of the meal, Wu Ming 3b). I had interviewed Wu Ming 1 and his collaborators for my blog some years ago, where he spoke with me about his interests in "multitudinous authorship, crossmedia storytelling, world making, identity games, RPG guerrilla warfare, old/new media collision, copyleft-oriented practices, media hoaxes and so on).” This creative collective has written some top-selling novels, such as Q and 54, but they have also spearheaded the Luther Blissert cultural movement, which has conducted any number of pranks and hoaxes to shake up the media establishment in his country. Wu Ming 1 wrote the introduction for the Italian language edition of Convergence Culture, and we've remained in close contact ever since. We had a great discussion, comparing the ways American and Italian activists have responded to the economic crisis, debating my current interests in fan activism, pondering the reasons why social media has played out differently in America and Europe, sharing Wu Ming's new transmedia projects, and above all, assessing current struggles over intellectual property. We were also joined at this meal by Giovanni Boccia Artieri, an expert on social media, who is on the Faculty of Sociology at the University Carlo Bo of Urbino.

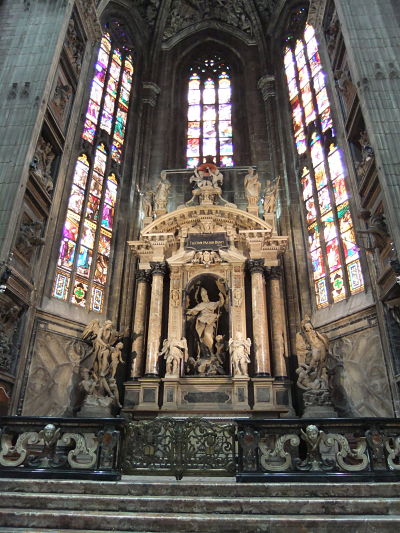

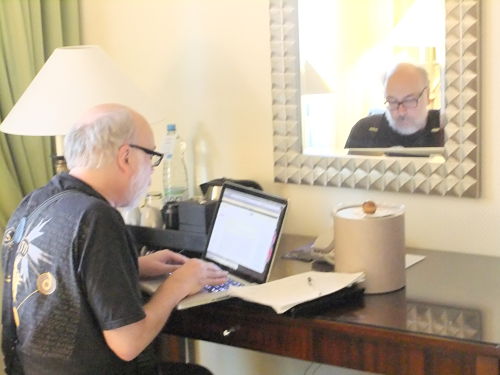

Artieri was instrumental in getting me invited to speak at his university during the festival. Wu Ming 1 attended and has shared these notes and audio files of the presentation. This photograph, taken during the talk, gives a hint at the very very baroque environment in which my remarks were delivered.

Afterwards, I was taken to lunch by Veronica Innocenti, who has written extensively about television seriality, and some of her faculty colleagues. Meanwhile, Cynthia had some of the American film studies crowd for a day trip to nearby Ravenna, a town overflowing with sixth century churches, which include intricate mosaic work.

Here, you see Cynthia with Virginia Wright-Wexman, Susan Olmer, Donald Crafton, and John Huntington, taken by their tour guide on this exposition.

Bologna, itself, is a delightful place to visit, characterized by long arcade-like walkways and narrow winding streets, often full of bikes and motorcycles.

I was much taken by this fountain, near the center of the city, which seems racy even by European standards, whether we are looking at the ways the women are shown fondling their own breasts (part of the mother's milk fixation observed earlier)

Or the proud display of certain elements of the male anatomy.

Somehow, the juxtaposition of the two leaves this fountain a particularly charged space in my memories of European waterworks. I would say that this guy's "having a party in his pants", if he was wearing any.

I mean no great insult to Italian food, which is everything you imagine it to be, and then some. We dove deep into one great plate of pasta after another across our various legs in Italy, and I think my number one take away from the trip is Prosciutto and Melon, which goes down really well in the sweltering heat we had been experiencing since Budapest. But, by this point in the trip, we had been in Europe for going on two months, having one exotic meal after another. And, I found myself more and more being drawn towards American fast food places, like the McDonalds depicted here. McDonalds functions as the unofficial American Club across Europe -- a place you can go where you recognize pretty much everything on the menu and where you know precisely what you are going to get, where you can -- usually -- get ice in your drinks, where people around you are speaking English, and where you can strike up a conversations with anyone at any table and likely get some fresh news from home, assuming your sense of home is North America between the Atlantic and the Pacific.

My graduate mentor, David Bordwell, was scheduled to participate in a panel near the close of the film festival, having a public conversation with Dave Kehr, who currently writes a column on dvd releases for the New York Times, who maintains maintains the blog Reports from the Lost Continent of Cinephilia, and who recently published a book of his film reviews from the Chicago Reader, When Movies Mattered: Reviews from a Transformative Decade. The panel was supposedly about the current state of Cinephilia, though our discussion ranged pretty broadly across historic and contemporary film cultures. As the title of Kehr's works suggest, he thinks that something vital has been lost in contemporary audiences' relationship to cinema, reporting dwindling attendance at retrospective screenings in New York City, and expressing concern that fewer and fewer classic works are making the transition across each new media platform. My own response was, characteristically, a bit more optimistic, so the exchange was a lively one, which I enjoyed very much. It was also fun for me to be speaking some place where I seemed to be better known as the author of What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and The Vaudeville Aesthetic than for Textual Poachers or Convergence Culture, and it was fun to use my extensive knowledge of other forms of media fan culture to tweak some of the pretensions of the art house crowd.

http://vimeo.com/44974590

COMING SOON: THE CRADLE OF CIVILIZATION