¡Presente!: A Day Without Immigrants and the Politics of Absence

by Emily Rauber Rodriguez

Civic Imagination: The Ironic Use of Speculative Fiction

The idea of a group of people disappearing on a mass scale—the core imaginative concept in making this strike an effective demonstration—is not new within public consciousness. It conjures serious implications of mass expulsion or even genocide, both of which have direct connections to recent history. However, it also handily borrows from the familiar, arguably speculative, narratives of the Christian rapture and its agnostic American cousin, alien abduction, both of which present alternative interpretations of reality. Latin Americans have a connection to all of these disappearance narratives: the genocide of indiosat the hands of the Spanish invaders; a status as an overwhelmingly Christian-majority continent; and a sordid history of political opponents becoming desaparecidos—literally, “disappeared.”

Latinos, however, have been historically absent throughout most of mainstream speculative visual fiction, a choice that’s all the more resonant when considering that the majority of makers of these texts are white Americans. As John Leguizamo joked in his stand-up special, Freak(1998), the fact that there were no Latinos on Star Trek“was proof that they didn't plan on keeping us around” in the future (Merla-Watson and Olguín 2017, 8). Similarly, Curtis Marez notes the lack of Latino farmworkers in Star Wars, but draws attention to the “power of their animating absence” as a sign of a reactionary move back toward the image of the white American farm boy (2016, 135). In both cases, the lack of Latinos could be intentional or unintentional, but either way demonstrates a larger issue whereby their voices and faces aren’t considered a significant part of these speculative futures (or distant pasts). As Cathryn Josefina Merla-Watson and B.V. Olgun wrote, “Being discursively cut outof the future is tantamount to being cut off from the future” (2017, 8). Similarly, repeatedly ignoring Latinos in these fictional visions of the future seems to suggest that Latinos also already being ignored in the present reality.

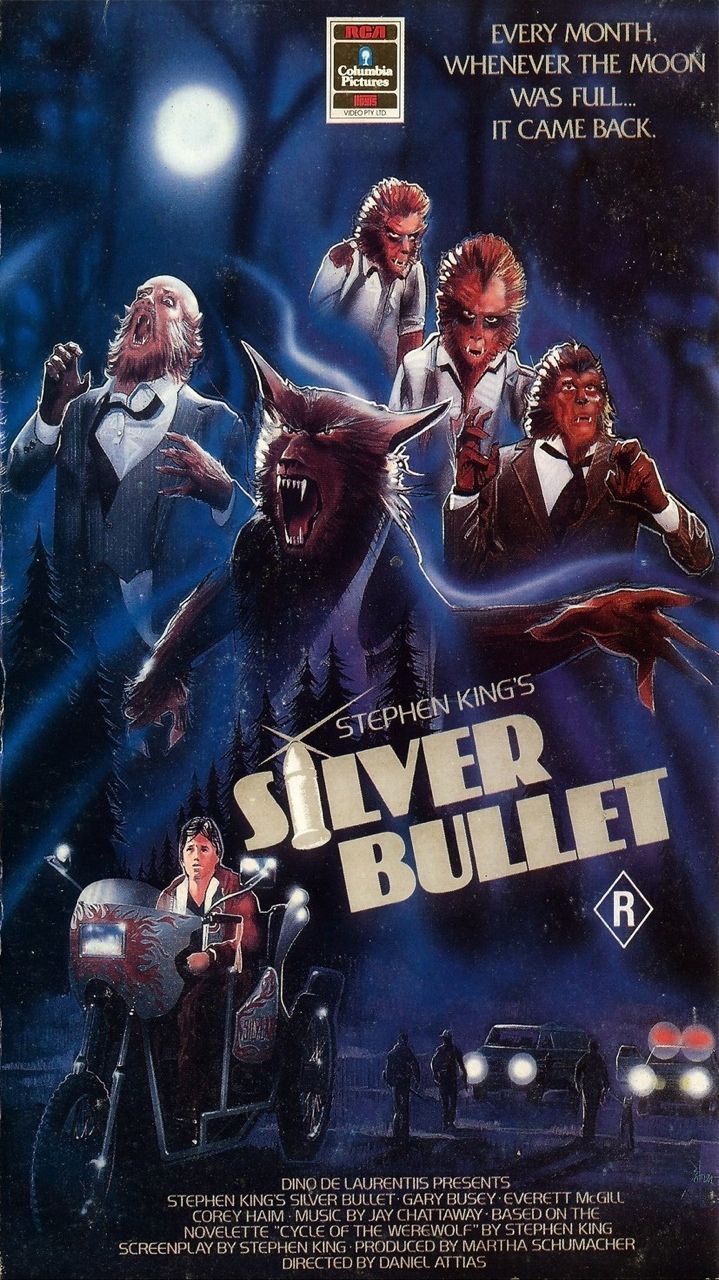

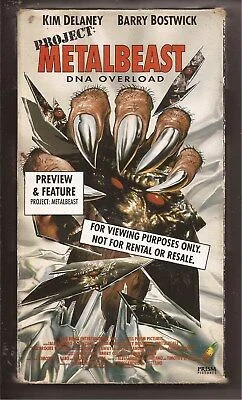

Instances of speculative fiction created by marginalized groups, thus, become even more important objects of study. As Chicana scholar and activist Gloria Anzaldua wrote, imagination “has the capacity to extend us beyond the confines of our skin, situation, and condition so we can choose our responses. It enables us to reimagine our lives, rewrite the self, and create guiding myths for our times” (2002, 5). For marginalized groups—those facing racism, poverty, or other discrimination on a daily basis—the specter of future relief from their current struggles seems particularly compelling. Indeed, Latino speculative fiction often draws on presenting solutions to or escapes from real-life issues. William A. Calvo-Quirosnotes that “the Chican@ speculative imaginary deeply intertwines sociopolitical and historical oppressive experiences and engenders a unique typology of speculative productions that emerge from the margins for the margins” (2017, 40). A Day Without a Mexicanfollows this closely, as its future is situated in the otherwise very realistic setting of Los Angeles. Furthermore, the speculative element exists primarily to call attention to the sociopolitical message of the film, not as a way to show off CGI creatures or create a visual spectacle for the audience.

Indeed, although the film uses wacky humor and fantastical imagery, it constantly reminds viewers of its connections to the real world. Both the short and the feature are shot in mockumentary style, using faux interviews, news reports, and B-roll footage, creating a sense of reality. The filmmakers were directly inspired to make the short after witnessing the passage of Proposition 187 in California in 1994, which would have restricted undocumented people from using state services and depended on drawing conservative voters’ ire against Latin American and Asian immigrants. The proposition received support from Governor Pete Wilson and did win the popular voter referendum, though it was later declared unconstitutional. Still, anti-immigrant sentiments remained stoked. Though neither film directly acknowledges Proposition 187, they do incorporate references to the real-life proceedings, such as the character of an anti-immigrant politician with an undocumented immigrant housekeeper; the same situation undercut the senatorial campaign of Republican nominee Michael Huffington. Both films are also interspersed with textual data that emphasizes their connection with reality; for instance, two teachers complaining at how much their workload has increased without their Latino colleagues are juxtaposed with a text banner proclaiming that “20% of California K-12 teachers are Hispanic.” The film’s marketing also called attention to its direct real-world application: to make use of burgeoning mid-2000s viral media, the producers put up a billboard in Hollywood that read: “On May 14th, there will be no Mexicans in California,” along with the movie website’s URL. The film openly invited its viewers to imagine the speculative scenario of the film occurring in their reality, which, ultimately, is what the protest organizers chose to attempt to reenact.

Fundamentally, both the film (explicitly) and the boycotts (implicitly) depended on an ironic deployment of civic imagination. Gianpaolo Baiocchi, et al. (2014, 55)defined the civic imagination as “the ways in which people individually and collectively envision better political, social, and civic environments.” For some people, this better future might indeed come from the perceived community solidarity engendered by all-white, cultural homogeneity; protecting the ethnic and racial uniformity of their group from perceived outsiders—immigrant, Latino, or otherwise—thus becomes their primary civic drive. In essence then, a Day Without Immigrants presented the ideal future of these white supremacists: a world with no immigrants. This technique may seem counterintuitive in that, in order to critique that view, these outsiders should assist in orchestrating their own disappearance. However, the boycotts themselves also made an appeal to community solidarity—only in their case, they appealed to a sense of diversity and togetherness, rather than racial homogeny. Protestors likely hoped that their absence would not only be noticed, but missedby the larger, non-overtly racist population. The discursive purpose of the boycott, then, was to enact the supremacists’ civic imagination as a temporary reality, and, hopefully, prove that it was unfulfilling and even unrealistic. By presenting this unsatisfactory future, it could push more indecisive people to reject that vision and move towards something else. The Day Without Immigrants’ reliance on ironic civic imagination, however, meant that the protestors did not get a chance to present their positive vision of their future, which could explain the lack of direct or continuous results from this action.

While Elisabeth Soep (2016)notes oversimplification as a potential risk of activist engagement through new media, in this case, the simplicity of the plan was perhaps the main reason for its successful spread. While the flyers made the event visible and easy to share on social media sites, the boycotts’ concept—even if one hadn’t seen the film A Day Without a Mexican—was easy enough to explain in the length of a tweet or brief conversation. This correlates to the film’s original format as a short, concept film—with only a few minutes to capture the audience’s attention, the filmmakers of A Day Without a Mexicanhad to distill their intended message into an uncomplicated story and easy-to-envision fictional world. The short film format also necessarily requires viewers to fill in the gaps with their own experiences. Similarly, a simple protest format like “don’t go to work or school” could be enacted in many different ways, thus allowing people to extract the most meaningful interpretations for themselves in how they chose to participate.

The Day Without Immigrants’ conceptual strategies are especially important to note, given its reliance on absence as a driving, yet easily unnoticed, force. In her introduction to This Bridge We Call Home, Anzaldua defines empowerment as coming “from ideas—our revolution is fought with concepts, not guns, and it is fueled by vision” (2002, 5). In this sense, the Day Without Immigrants is nearly a textbook example of empowerment, as it depended foremost on the spread of an idea. If everybody encountered a few missing people throughout their day and did not connect those absences to the strike, the protest would have imparted no significant meaning. And surely, there must have been many instances during this boycott where an immigrant’s absence was indeed not noticed, or at least not connected to the larger action. The film also begins with most people noticing one or two people missing, then having to piece together the larger significance. The most essential element of this movement, then, was to spread the ideaof the strike, and, indeed, of that vision of the future with no immigrants. The concept foremost gave meaning to the actions, and luckily the concept was mostly strong enough to remain in place even when the protests themselves were, by design, invisible.

Part of the film’s cult appeal was its obvious low-budget aesthetic, aided by the mockumentary style and intentionally shoddy graphics, indicating to viewers that it was an outsider and not part of the Hollywood mainstream. The homemade, networked spread of the Day Without Immigrants protest also demonstrated a bottom-up, grassroots process of participatory politics. Kahne, et al. (2015, 41)have defined as participatory politics as “interactive, peer-based acts through which individuals and groups seek to exert both voice and influence on issues of public concern.” The boycott here was planned by the people and for the people, with no official governmental or organizational backing. While protestors are often suspicious of activist organizations—see recent criticisms of the Women’s March (Valens 2018)—this movement offered an alternative to traditional political participation. Like an indie film, the Day Without Immigrants’ lack of mainstream backing seemed to ensure that its message was the most important element; there was no higher power waiting to gain a profit from the labor of the protestors. Both the film and the movement also spread primarily through word-of-mouth, offering each participant a direct connection into the event, likely by somebody they already knew. This interpersonal connection instantly built a community around each object, allowing people to forge social bonds even beyond the immediate context of the film and the protest.

Finally, it’s interesting to note the reverse format of these Day Without Immigrants protests, which made visible people temporarily invisible: protests that seek to make the invisible temporarily visible. In 2015, for instance, marchers in Madrid gathered via hologram to oppose a law preventing mass protests—technically following the law through their bodily absence, yet also calling attention to its danger through their digital presence (Mullen 2015). Similarly, advocacy group Avaaz recently displayed 7000 pairs of shoes on the Capitol lawn, to represent the number of children who have died by gun violence since the Sandy Hook shooting (Killough 2018). In both cases, the protests call attention to people who cannot be present—due to specific failings of the legal system—by claiming physical space for their absent bodies. These striking, ghostly images also contrast the typical images of a mass of people at other protests, allowing them to stand out in a crowded visual media landscape. In some ways, the immigrant story could translate well into one of these types of protests, perhaps representing those who have been lost. But, though they may not be able to control the consequences, immigrants still have the agency to choose whether to make themselves visible. Through their choice to make themselves absent at the Day Without Immigrants, protestors could make a powerful statement that acknowledged their precarious position, while also declaring that they were not invisible—yet.

Conclusion

By using a simple, well-known speculative fiction concept, the Day Without Immigrants protest was able to spread easily, even without the immediate context of the film, A Day Without a Mexican. Ultimately, the Day Without Immigrants wasn’t entirely successful in terms of policy changes, and truly universal participation among all immigrants in all walks of life likely would have had impossible-to-ignore consequences. However, the reality is that this type of protest action could never reach every immigrant in the country, due to their economic and social precarity. Some undocumented immigrants might also resent having to move into the shadows voluntarily, when that is how they are forced live every day. Similar campaigns have appeared over the past year on a more frequent basis, though—including immigrants rights’ organization Cosecha’s 2017 and 2018 May Day boycotts—indicating that absence is still an evocative mode of protest.

Immigrants are bound together primarily by virtue of their shared “uncitizenship” (by birth) of their country of residence, making their civic participation a perhaps less obvious and more intentional act. As a somewhat organically formed expression of activism—shaped and remixed by its participants as it developed—a Day Without Immigrants serves as a reminder to future movements to truly consider the needs of its members, not only in political goals, but also in preferred modes of participation. Although mass marches may be one way to voice the messages of a community, it is, by far, not the only way.

References

Anzaldua, Gloria. 2002. “(Un)natural Bridges, (Un)safe Spaces.” In This Bridge We Call Home: Radical Visions for Transformation, edited by Gloria Anzaldua and AnaLouise Keating, 1–5. New York: Routledge.

Baiocchi, Gianpaolo, Elizabeth A. Bennett, Alissa Cordner, Peter Taylor Klein, and Stephanie Savell. 2014. “The Civic Imagination.” In The Civic Imagination: Making a Difference in American Political Liife, 52–76. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publications.

Calvo-Quitos, William A. 2017. “The Emancipatory Power of the Imaginary: Defining Chican@ Speculative Productions.” In Altermundos : Latin@ Speculative Literature, Film, and Popular Culture, edited by Cathryn Josefina Merla-Watson and B. V. Olguín. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press.

Chishti, Muzaffar, Sarah Pierce, and Jessica Bolter. 2017. “The Obama Record on Deportations: Deporter in Chief or Not? | Migrationpolicy.org.” Migration Policy. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/obama-record-deportations-deporter-chief-or-not.

Costanza-Chock, Sasha. 2014. Out of the Shadows, Into the Streets: Transmedia Organizing and the Immigrant Rights Movement. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2016. “2016 Hate Crime Statistics.” https://ucr.fbi.gov/hate-crime/2016.

Gamber-Thompson, Liana, and Arely M. Zimmerman. 2016. “DREAMing Citizenship: Undocumented Youth, Coming Out, and Pathways to Participation.” In By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism, edited by Henry Jenkins, Sangita Shresthova, Liana Gamber-Thompson, Neta Kligler-Vilenchik, and Arely M. Zimmerman. New York: NYU Press.

Heredia, Luisa Laura. 2016. “More than DREAMs.” NACLA Report on the Americas48 (1): 59–67.

Kahne, Joseph, Ellen Middaugh, and Danielle Allen. 2015. “Youth, New Media, and the Rise of Participatory Politics.” In From Voice to Influence: Understanding Citizenship in a Digital Age, edited by Danielle Allen and Jennifer S. Light, 35–55. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Killough, Ashley. 2018. “Activists Place Thousands of Shoes on Capitol Lawn in Gun Death Memorial.” CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2018/03/13/politics/shoe-memorial-congress-gun-violence/index.html.

La Torre III, Pedro De. 2014. “Out of the Shadows: DREAMer Identity in the Immigrant Youth Movement - ProQuest.” Latino Studies12 (3): 449–67.

Lucas, Ryan. 2017. “Hate Crimes Up In 2016, FBI Statistics Show : NPR.” NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/11/13/563737883/hate-crimes-up-in-2016-fbi-statistics-show.

Marez, Curtis. 2016. Farm Worker Futurism.University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1c2crhk.

Merla-Watson, Cathryn Josefina, and B. V. Olguín. 2017. “Reassessing the Past, Present, and Future of the Chican@ and Latin@ Speculative Arts.” In Altermundos : Latin@ Speculative Literature, Film, and Popular Culture, edited by Cathryn Josefina Merla-Watson and B.V. Olguin, 492. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press. http://www.washington.edu/uwpress/search/books/MERALT.html.

Molina, Natalia. 2013. How Race Is Made in America : Immigration, Citizenship, and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts. Oakland: University of California Press.

Mullen, Jethro. 2015. “Spanish Activists Hold Hologram Protest in Madrid.” CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2015/04/12/europe/spain-hologram-protest/index.html.

Robbins, Liz, and Anniie Correal. 2017. “On a ‘Day Without Immigrants,’ Workers Show Their Presence by Staying Home - The New York Times.” The New York Times, February 16.

Soep, Elisabeth. 2016. “Youth Agency in Public Spheres: Emerging Tactics, Literacies, and Risks.” In Civic Media: Technology, Design, Practice, edited by Eric Gordon and Paul Mihailidis, 393–420. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stein, Perry. 2017. “Restaurants, Schools Close in ‘Day Without Immigrants’ Protest - The Washington Post.” Washington Post, February 16.

Valens, Ana. 2018. “The Women’s March Is Under Fire for Tweeting Barbara Bush ‘Rest in Power.’” The Daily Dot. https://www.dailydot.com/irl/barbara-bush-womens-march-feminists-twitter/.

Zong, Jie, and Jeanne Batalova. 2017. “Frequently Requested Statistics on Immigrants and Immigration in the United States | Migrationpolicy.org.” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states.

Zoppo, Avalon. 2017. “Employees Across U.S. Fired After Joining ‘Day Without Immigrants’ Protest.” NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/employees-across-u-s-fired-after-joining-day-without-immigrants-n722991.

Zuckerman, Ethan. 2013. “Cute Cats to the Rescue? Participatory Media and Political Expression.” In Youth, New Media and Political Participation, edited by Danielle Allen and Jennifer Light. Cambridge: MIT Press.