Cult Conversations: Interview with Craig Ian Mann (Part II)

/Could you expound on your own question, rhetorical though it may be: “are we so precious about horror's low-brow status that we must pretend it means nothing?” Do you think that horror is still largely disparaged as low-brow? Who are the “we” that may be “so precious” about such status and what might be the reason for this preciousness?

I think there's ample evidence that horror is disparaged. You only have to look at the media articles that pop up every time a new A24 film is released. While I tend to love A24's horror output, there's always a larger sense that each film is somehow a "better" or new kind of horror movie that puts to bed decades of apparently meaningless slash-and-stalk nonsense – which is, of course, total rubbish. So as to whether there is a larger cultural perception that horror is low-brow: yes, definitely. I think there always has been and always will be to some extent. You'll always find a critic who latches onto the latest indie horror sensation as a turning point and unnecessarily tries to argue for the genre's sudden transition from apparent trash to supposed art.

On the other hand, though, I think we are seeing a wider acceptance of horror. I think part of that is the attention that the academy has been giving to the genre since the 1980s and 1990s. In recent years it has also been due to companies like Arrow, Eureka, Shout Factory, Powerhouse/Indicator and so on. By giving horror films prestige treatment, releasing them in beautifully presented packages with an embarrassment of special features, those companies have aided in establishing the genre as a subject for mainstream critics. And the wider acceptance of horror is starting to show in some pretty clear ways: look at the BFI's Stephen King on Screen season. A retrospective of King adaptations (and a selection of horror movies chosen by King) would have been unthinkable for the NFT ten years ago. So it's great to see a wider celebration of popular cinema – though I'll add that I'm extremely wary of framing these changes as a "legitimisation" of horror, as it has always been a meaningful and versatile genre.

Anyway, to expand on the specific point I was making: I really enjoy industrial studies of horror cinema, and it's obvious that there will be a tendency in those works to pitch horror films as saleable products first and foremost (just as I prioritise historical context – it's a natural outcome of taking a certain approach). However, I think it's unnecessarily oppositional to set up those commercial imperatives in direct counterpoint to any framework that attempts to derive cultural meaning from horror. Just because horror films are – sometimes, though not always – designed for mass consumption, that doesn't mean that they don't carry meaning. I think there is a sense in some industrial studies that we must protect horror from an intelligentsia that would ruin its mass market appeal, and I just don't understand that argument. In short, just as I'm wary of attempts to legitimise horror films, I'm also wary of attempts to delegitimise them: to me it seems odd to suddenly reframe horror films as high art, but it's also problematic to reduce them to economics and shut out thematic concerns. Methodological approaches can and should co-exist and intersect.

There have been many accounts in press discourse recently arguing that horror cinema is undergoing a renaissance, or resurgence, of sorts. Do you agree with claims that we are witnessing a new ‘golden age’ of horror cinema?

Well, I am co-organiser of Fear 2000 (with Sheffield Hallam University colleagues Rose Butler and Shelley O'Brien), which is an annual conference series dedicated to horror media in the twenty-first century – so I certainly think we're in a particularly interesting period for horror films, and there's a lot to say about their continued relevance, popularity and significance.

I'm a particular fan of a group of American filmmakers that either made or are currently making their names producing independent horror movies: Ti West, Glenn McQuaid, Adam Wingard and Simon Barrett, E.L. Katz, Jim Mickle and Nick Damici, Ted Geoghegan, Joe Begos, Mickey Keating, Ana Asensio. These are all writers and directors (and writer-directors) that have some connection to Larry Fessenden, a writer, director, producer and actor who deserves to be more widely studied and who has been involved – in one way or another – in some of the most astonishing horror films made since the turn of the millennium (in fact, several of them have made films produced or co-produced by Glass Eye Pix, Fessenden's production company). So I think American horror is alive and well, and I'm also an avid follower of contemporary British, Canadian and Australasian genre cinema.

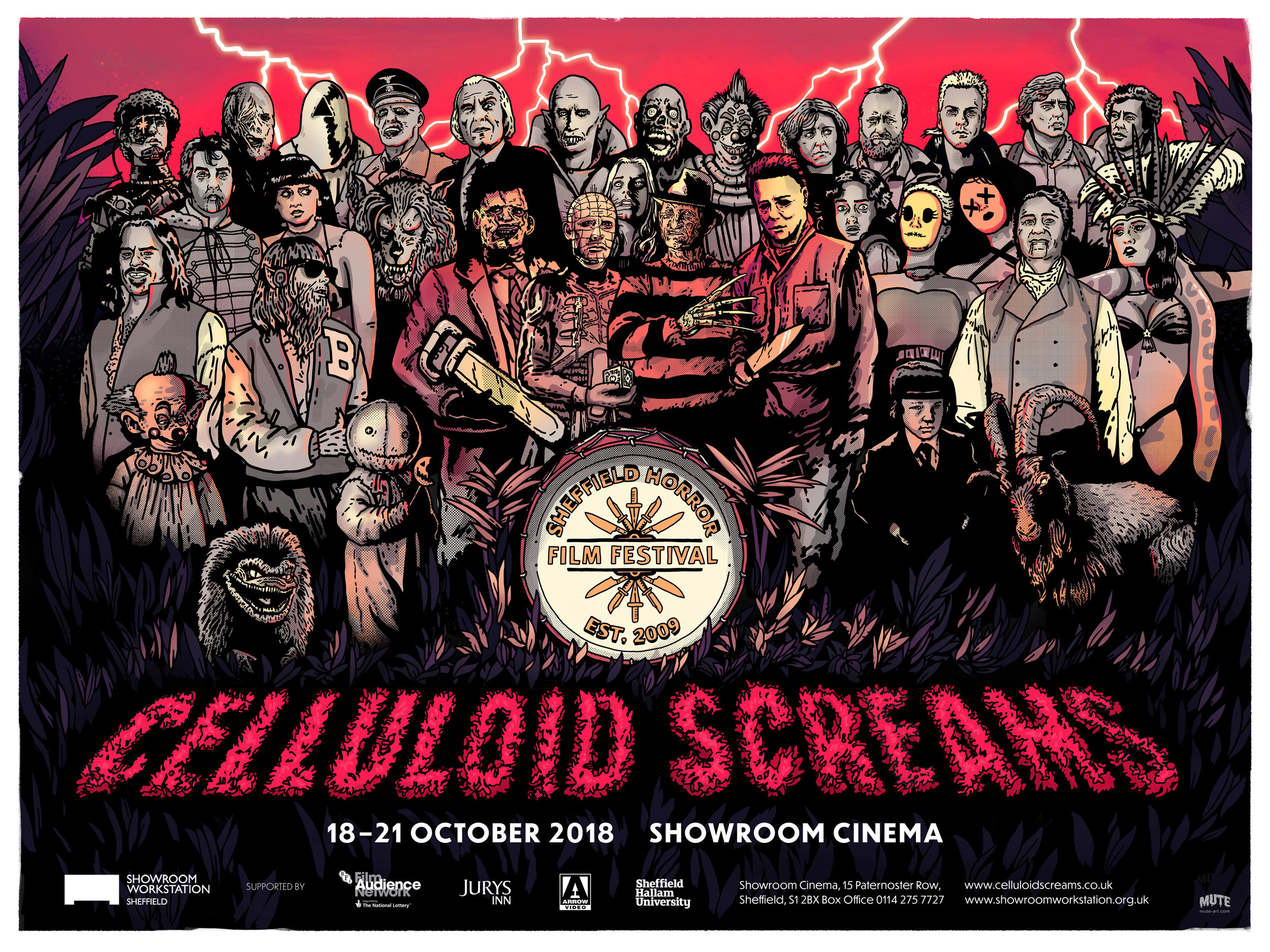

And I would agree – with a couple of extreme caveats – that there is some truth to the idea that we are witnessing a "golden age" of horror, but not for the reasons often cited in the popular press. It isn't a matter of quality for me, which seems to be how this debate is most frequently framed. I think we have seen horror resurge in large part because of new opportunities that make it easier for great movies to find a platform. The increasing inclusion and appreciation of horror films on the festival circuit has come to play a huge part in this over the last few decades, as has the increasing number of dedicated regional genre film festivals – such as Sheffield's Celluloid Screams or Nottingham's Mayhem – and boutique home-video distributors. And we're also starting to see the benefit of streaming services like Netflix, Amazon Prime and Shudder as an alternative distribution and exhibition network.

Horror films are finding an audience like never before through these new avenues, which in turn has enabled companies like Blumhouse and A24 to find success selling horror films through the more traditional theatrical routes. So there's a sense that horror cinema is not necessarily getting "better" as such, but that more people are able to see and engage with it. It is certainly a popular and mainstream genre at the moment in a way it hasn't been since the 1980s.

What I don't agree with, however, is the widespread idea that any current "golden age" has occurred because horror films are becoming more meaningful, which ties into our discussion around cultural approaches to horror cinema and attempts to legitimise or delegitimise the genre. Horror films have always been meaningful, and the fact that contemporary genre movies have been clearly influenced by the cultural circumstances of their production – e.g. Get Out (2017) – is nothing new. We don't need to invent new terms for certain groups of films – and I'm primarily talking about the particularly contentious "post-horror", but I'll make clear I'm also thinking of terms like "mumblegore", "deathwave" and so on – to elevate them above the pack or differentiate them from the horror of decades past.

I think the idea that a certain crop of contemporary horror films are somehow more thematically interesting or politically engaged than their predecessors and/or contemporaries is pretty problematic. Horror has always been a rich, varied and versatile genre; creating a new label to describe a select cycle that happens to have met with praise just seems be a way to justify and legitimise enjoying a type of film that might otherwise be considered too trashy for the critical mainstream. But we've been here before; as Silence of the Lambs (1991) was apparently a "psychological thriller," so Get Out is a "social thriller." These kinds of labels will come back around again (and sadly it will probably be sooner rather than later).

How would you respond to Alice Haylett Bryan’s argument about horror (quoted in The Guardian)?

“Certain subgenres of horror are undoubtedly getting more extreme, but this is the case across culture as a whole, with computer games and television programmes such as The Walking Dead. We are now living in an age where real acts of violence, and indeed death, have been screened on Facebook and YouTube. Could it not be argued that this desensitizes viewers on a more fundamental and concerning level?”

Well, I suppose there are three parts to this: whether certain facets of the horror film are becoming increasingly extreme, whether they desensitise us to violence, and whether we should find the real-life horrors available to view on the internet far more troubling. As for the first question, I think the trend for extreme imagery in mainstream horror has passed for the most part. The torture porn cycle has come and gone – with a brief revival in Jigsaw (2017), a film that was ironically criticised for not being gory enough – and the New French Extremity movement seems to have naturally played itself out. The most recent French horror film to be actively marketed as being "extreme" was Raw (2016), which became the subject of an awful lot of hype due to reports of overdramatic reactions on the festival circuit, but the film itself is actually relatively tame. I think there are still some very interesting examples of visceral, sanguinary horror cinema out there, but you have to go digging a little deeper now. Baskin (2015) and Housewife (2017), two films by Turkish filmmaker Can Evrenol, are the first examples that come to mind. But I think the trend for pushing the envelope that was at the forefront of horror in the 2000s is largely over now.

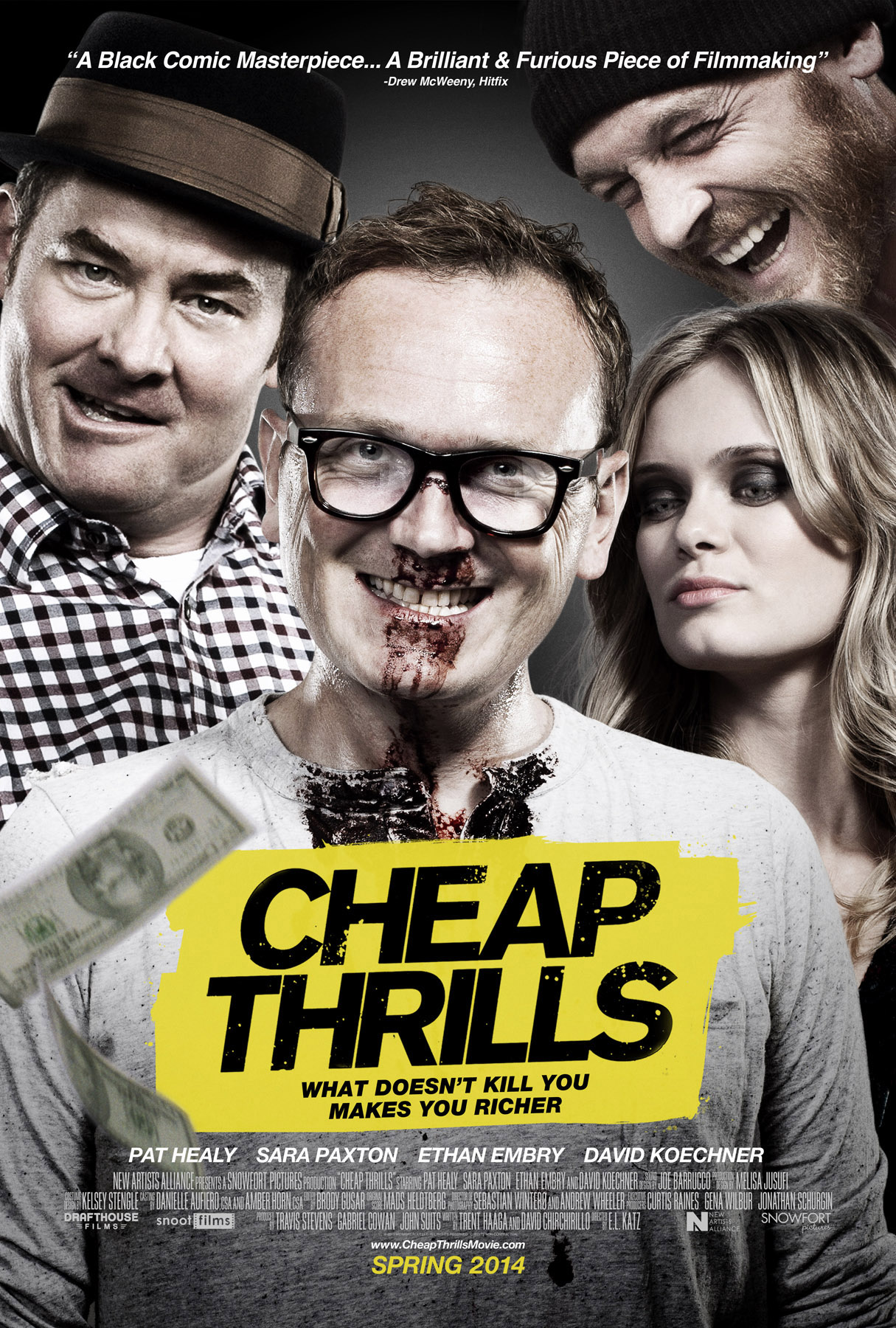

It's probably not surprising to hear that I don't subscribe to the idea that horror desensitises us to violence. As a culturalist, my stance is that horror films can actually provide a form of catharsis and allow us to work through real-world issues. There has been a particular cycle of American horror films since 2007, for example, that has arisen from the cultural moment following the financial crisis and the Great Recession. These films – so I'm talking about movies like The House of the Devil (2009), The Innkeepers (2011), Cheap Thrills (2013), You're Next (2013), Starry Eyes (2014) and Don't Breathe (2016), for example – often concentrate on poor, disenfranchised and flawed protagonists who find themselves in horrifying situations (sometimes by choice and other times not), and don't walk away because they simply can't afford to. So actually I think horror films can be quite cathartic.

And yes, I think real-world violence is far more concerning than fictional violence, but I think that has always been true and isn't confined to the age of the internet (though, it's undeniable that if you want to find images of real death it's far easier to do now that it has ever been before). When the likes of Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Last House on the Left (1972) and Deathdream (1974) were released, the average American could watch someone being blown-up in Vietnam while eating their dinner. So I completely agree with Haylett Bryan, really – there are far more worrying things in the world than horror movies.

Well, Haylett-Bryan is also claiming that viewers have been “desensitized” by extreme horror. What are your views on whether or not horror cinema affects audiences to a degree that they are “desensitized” by on-screen violence and that this might impact everyday lives in relation to real-world violence?

I don't know if that is what Haylett Bryan is saying, exactly (her comments on desensitisation are in direct reference to real-world violence, after all). And I think we also need to think about what "desensitisation" actually means in this context. I suppose, on a fundamental level, the more you are exposed to fictionalised images of violence, the less they are likely to shock you next time you see them.

However, human beings are perfectly capable of distinguishing between fact and fiction, so if we are taking "desensitisation" to mean that horror has the potential to numb us to the many horrors of the real world or even encourage us to commit acts of violence ourselves: absolutely not, and I don't think Haylett Bryan is proposing that either. I don't want to speak for her, but I would imagine that she is simply trying to point out that – now that images of real death have proliferated on the internet and can be readily found and accessed – the media should probably stop agonising over the fact that people continue to watch and enjoy horror films.

What are you working on at the moment and what are your research plans for the future?

Well, I spent Halloween at Birmingham City University presenting on werewolf cinema as part of a research seminar series organised by Xavier Mendik and Charlotte Stevens. Since then I've been chipping away at Phases of the Moon, which is due either late 2019 or early 2020. That will be preceded by a Horror Studies article taken from the book; it focuses on the American werewolf films of the 1970s and should be published in the Spring 2019 issue.

I have a few other articles and book chapters that should see publication in the near future, including a piece for the Journal of Popular Film and Television on the relationship between Jim Mickle and Nick Damici's Mulberry Street (2006) and the post-recession economic horror cycle. I've also been working on some research outside of the horror genre and have just written a chapter for an upcoming collection on cult Westerns edited by Lee Broughton. Plans are also coming together for the next Fear 2000 conference, slowly but surely.

I have a number of plans for future research, including an edited collection to follow up on Phases of the Moon and a few monograph ideas. Nothing definitive yet, but I'd like to pursue a project on science fiction or the Western. There are also a number of individual films I'd like to take as a focus for a single volume. We'll see how things develop.

What five films do you think represent the best that Werewolf cinema has to offer and why?

That is a really tough question, but I'll certainly give it a go.

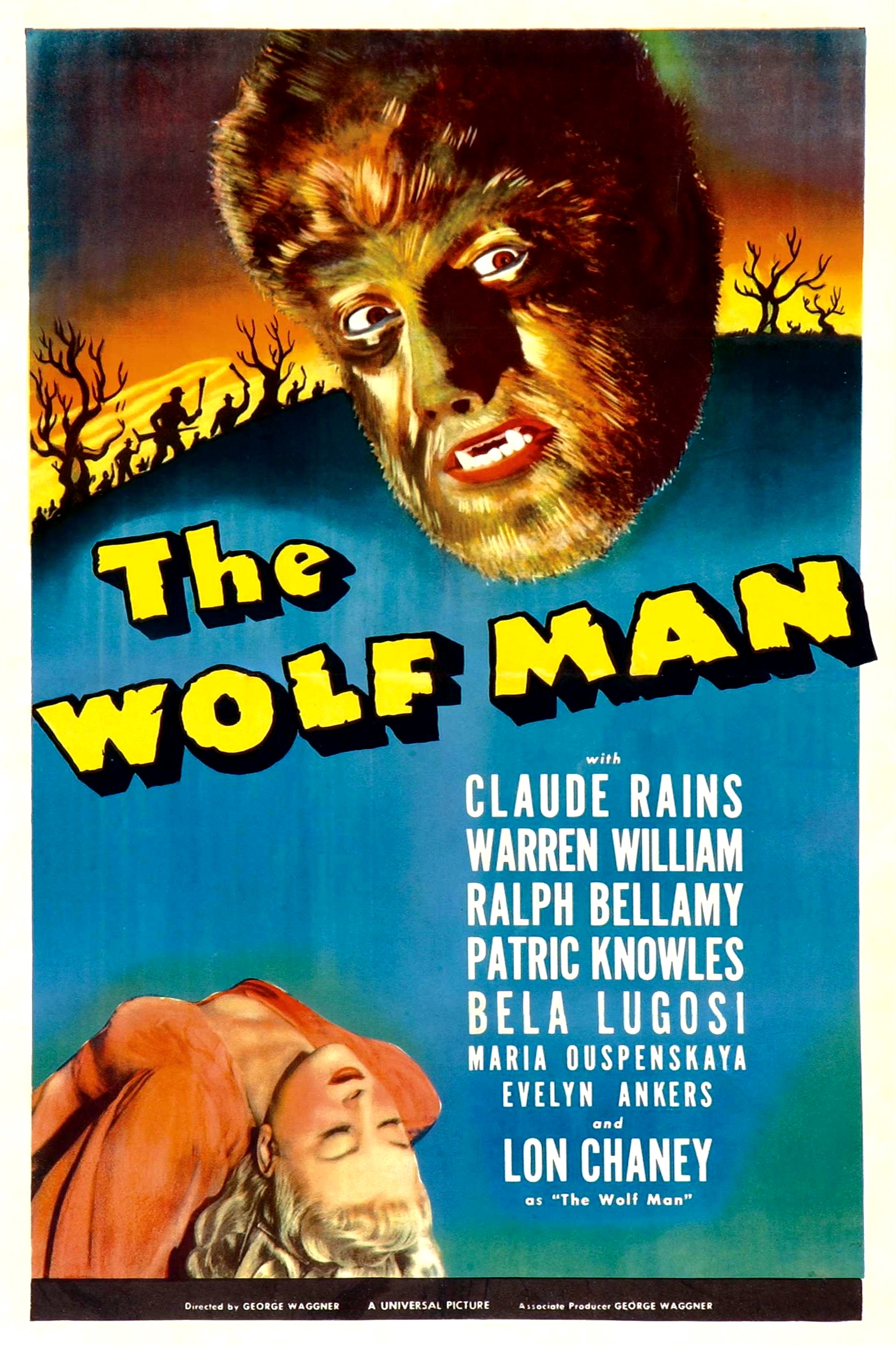

The Wolf Man (1941)

I think it's really hard to underestimate the importance of The Wolf Man for the development of werewolf cinema (and for the modern conception of werewolves in general). It's not the first werewolf film – as far as we know that honour goes to a lost silent short appropriately called The Werewolf (1913) – and it was predated by a couple of extant examples: Wolf Blood (1925) and Werewolf of London. However, it popularised a lot of the tropes we now associate with the monster: transformation linked to the moon, silver as a werewolf repellent, the painful and destressing nature of metamorphosis. All of these elements have their basis in folklore (and Werewolf of London had previously linked a werewolf's transformations with moonlight), but it was Siodmak who canonised them. It was also the popularity of The Wolf Man that led to an entire cycle of werewolf films in the 1940s: The Mad Monster (1942), The Undying Monster (1942), Cry of the Werewolf (1944), She-Wolf of London (1946), as well as RKO's closely related Cat People (1942). And, of course, it spawned three sequels of its own – four if you count Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). So while the first werewolf films predate The Wolf Man by nearly thirty years, it's certainly the most significant of the early examples.

I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957)

While The Wolf Man popularised a lot of the generic tropes we associate with werewolves, I Was a Teenage Werewolf is one of the most thematically influential werewolf films ever made. As the title suggests, this is the film that established the "teenage werewolf" trope and first used werewolfism as a metaphor for adolescent angst and teenage rebellion. These have remained some of the most prolific and consistent themes in werewolf cinema ever since. Without I Was a Teenage Werewolf, there would be no Teen Wolf (1985) and no Ginger Snaps (2000) – and you can still see its influence today in films such as When Animals Dream (2014), Uncaged (2016) and Wildling (2018). So what started life as a low-budget exploitation movie designed to cash-in on a burgeoning teen market has proven to be a major milestone in the development of werewolf cinema. It's just a shame that the only way to see it now is either on VHS or a bootleg DVD. I'm also a big fan of the other American werewolf movie of the 1950s: The Werewolf (1956), which updates the monster for the atomic age. It played as the B-picture with Earth vs. The Flying Saucers (1956), which is a double-bill I have replicated more times than I'd like to admit…

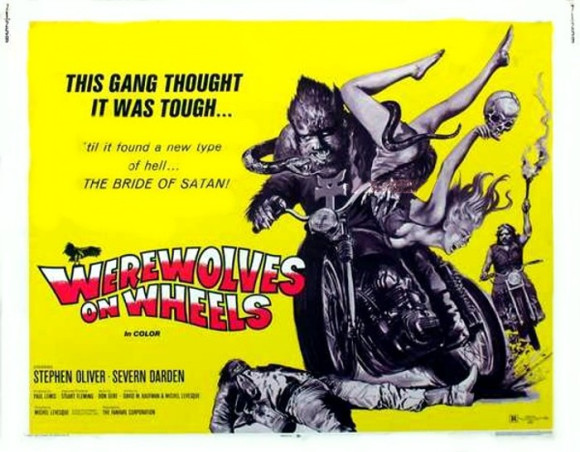

Werewolves on Wheels (1971)

First of all, Werewolves on Wheels has a title that no one in their right mind could refuse. But it's actually a much more serious film than you might think: it feels like a high-speed collision between Easy Rider (1969), Race with the Devil (1975) and a werewolf film – though I have no idea which other werewolf movie I would compare it to. It's definitely unique. It follows an outlaw biker gang that descends on an isolated temple in the middle of the arid United States and finds a group of Satanic monks living inside; by the time they leave the temple, half of the bikers have been placed under a curse that turns them into werewolves when the sun goes down. Aside from being a gloriously entertaining exploitation film, Werewolves on Wheels is the werewolf movie that most closely aligns with the "New Horror" movement as typified by the early works of George A. Romero, Wes Craven, Tobe Hooper, Bob Clark and so on. It has that apocalyptic feel, that sense of dreadful pessimism and that countercultural spirit that characterised so many independent horror films of the late 1960s and early 1970s. It's an utterly fascinating movie and one worth tracking down – it's available on Region 1 DVD, but for the full experience I recommend a late-night viewing of the limited-edition VHS release put out by Manor Video a few years ago.

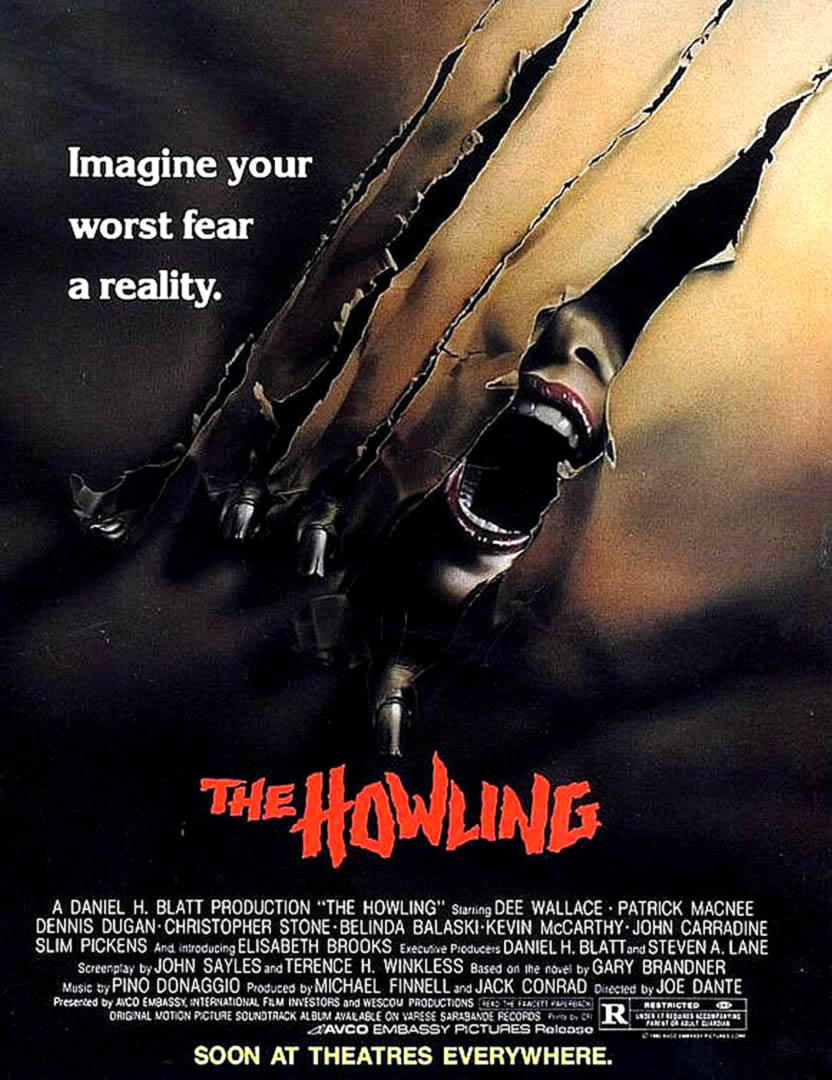

The Howling (1981)

This was an extremely difficult choice because I am also a huge fan of An American Werewolf in London and particularly Silver Bullet, which is the Gremlins or Fright Night (1985) of werewolf movies. But ultimately I think The Howling is probably the best werewolf film ever made. It was the first film to introduce what I call the "new werewolf": the huge, monstrous, lupine creatures that have been a mainstay of werewolf movies ever since. It also pioneered a new kind of transformation scene, abandoning the editing tricks used in previous decades and replacing them with a prolonged, visceral and grotesque sequence in which the film's werewolf antagonist goes through a graphic metamorphosis in front of his terrified victim (and it's all the more impressive for the fact that it was achieved on a pretty limited budget). Thematically, it has an interesting link with the body-horror imagery that was becoming so popular in horror cinema at the time, and – as you would expect from a film written by John Sayles and directed by Joe Dante – it's incredibly clever, self-aware and satirical, with a lot to say about the dark side of American culture in the early 1980s. So I'm a huge fan of The Howling, and it is certainly up there with The Wolf Man in terms of its influence. I will even admit to enjoying some of the sequels.

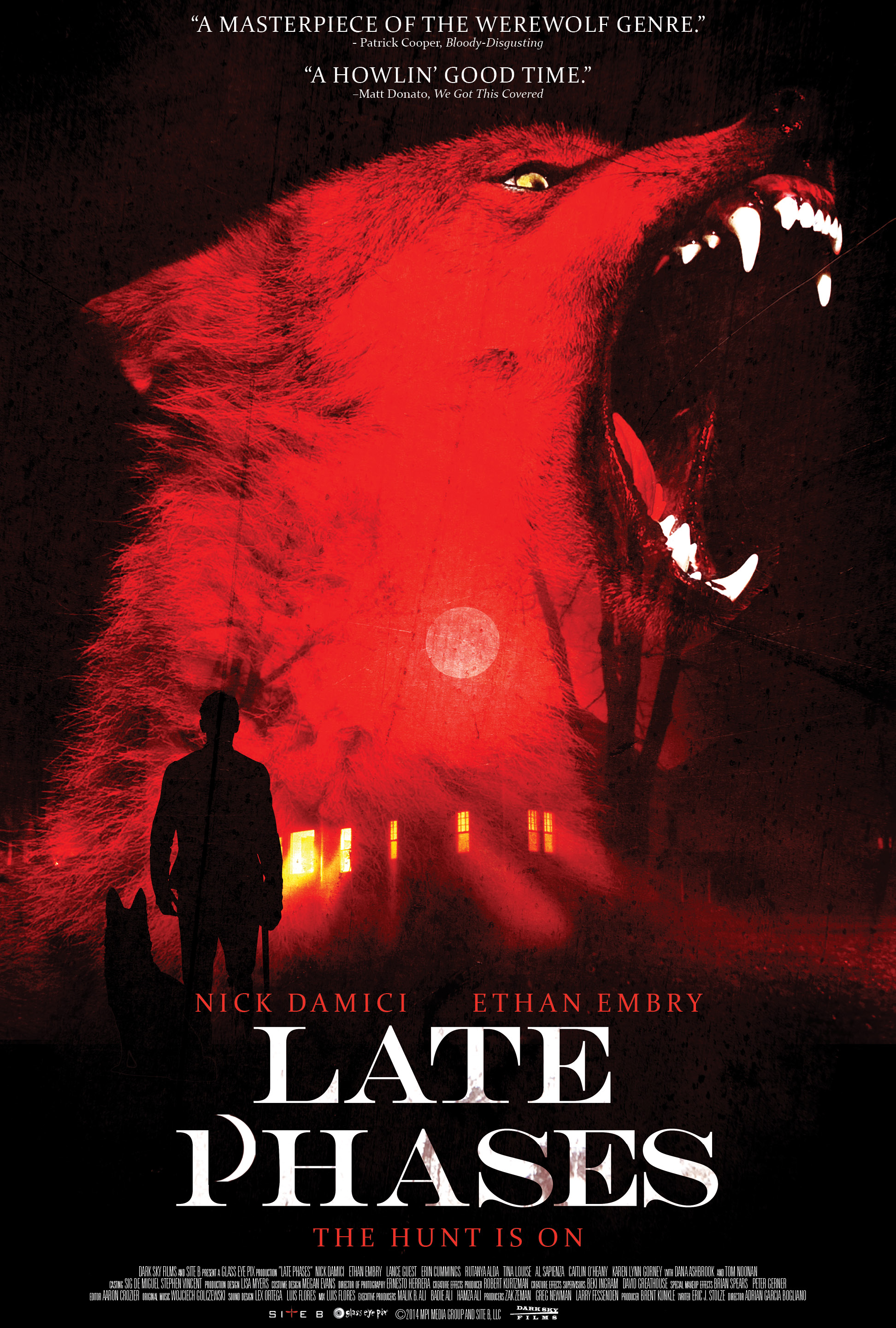

Late Phases (2014)

I think it's important to highlight a recent werewolf film, as there's an unfortunate tendency to write-off everything after the early 2000s – or even after 1981. Late Phases definitely had its supporters though; Bloody Disgusting called it a "masterpiece of the werewolf genre", and I would have no problem agreeing with that. It stars Nick Damici – who is one of my favourite actors – as a blind Vietnam veteran. At the insistence of his son, he moves into a retirement community on the edge of a forest that has become the feeding ground for a werewolf. It has an unorthodox structure, with all of the werewolf scenes in the first and third acts; the middle section follows Damici's character as he tries to discover the monster's identity. So it's essentially the meeting of Rolling Thunder (1977) and Silver Bullet, and it is every bit as good as that sounds. And as a blending of those two movies would suggest, it has some really interesting themes around militarism, religion and social conservatism. I don't want to say too much more because it's a film best seen cold, but I will say that I really like its unique werewolf designs – the creature effects are by Robert Kutzman, so there's some pedigree there. I've also noted above that I'm a big fan of Larry Fessenden, who produces (and appears in a great cameo role as a tombstone salesman).

Craig Ian Mann is an Associate Lecturer in Film and Television Studies at Sheffield Hallam University, where he was awarded his doctorate in 2016. His first monograph, Phases of the Moon: A Cultural History of the Werewolf Film, is forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. He is broadly interested in the cultural significance of popular genre cinema, including horror, science fiction, action and the Western. His work has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Popular Film and Television, Horror Studies and Science Fiction Film and Television as well as several edited collections. He is co-organiser of the Fear 2000 conference series on horror media in the twenty-first century.