Cult Conversations: Lovecraftian Myth and Paratextual Ripples in Popular Culture by Keith McDonald

/Keith McDonald

There is a scene in the 2016 film Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (dir. Gareth Edwards) where in order to extract information from Empire defector Bodhi Rock (Riz Ahmed) the mysterious Rebel faction leader Saw Gerrara (Forest Whitaker) introduces him to a blob-like tentacled creature named Bor Gullet. Gerrera explains the creature's power as it wraps its tentacles around the terrified Rook, “Bor Gullet can feel your thoughts. No lie is safe. What have you really brought me, cargo pilot? Bor Gullet will know the truth. The unfortunate side effect is that one tends to lose one’s mind.” This of course nods both visually and thematically to H.P. Lovecraft where human engagement with strange and powerful creatures leads to the splintering of the mind in what is in essence a psychic rape in the most popular film franchise on the planet. This is not surprising in some ways, Lovecraft’s contribution to Weird Tales was his main outlet and the pulp sensibility and genre focus was part of the soup of influences on the Star Wars mythos.

Mark Jones gives a comprehensive overview of Lovecraft’s influence on popular culture in his essay, Tentacles and Teeth: The Lovecraftian Being in Popular Culture, which acts as a starting point for the following discussion. Of course, there is paratextual merchandise using the image of Bor Gullet in the form of a ‘cutsie’ t-shirt on which it wears a cap with the word “Truth” written on it. If one doesn’t already exist, there will surely be a collectible figurine to be traded on the fan convention circuit and it is paratexts (models etc.) that will be the focus of what follows here.

One can only imagine what Lovecraft would make of the recent release of the Pop Vinyl Cthulu figure, but it is easy (and perhaps lazy) to imagine a less than enthusiastic response. There are thousands of Lovecraftian collectables in circulation in comic book outlets, at fan conventions and online. These are not always drenched in irony though, the majority of the models themselves are intricate, at times unnerving, and invocative of the memorable power of Lovecraft’s creations. The most popular of these creatures is Cthulu itself, which fittingly has a myriad of incarnations (including a plush child’s toy). Alongside this, there are coffee mugs, coasters, mobile phone cases, tote bags and jewelry, much of which can be bought through websites such as cthulushop.com where, when opening a new page to browse, you click on a tab which reads ‘Load more madness.’ This sees literary mythos turned into a growing commercial industry. No doubt some Lovecraft purists will baulk at this and see is as an anathema to the intentions of the author. However, this is Barthe’s concept of ‘the death of the author’ blended with monetized appropriation and user-generated content in physical form. The death of one author does not mean the death of the author’s creations and the ongoing curation of the writer’s incantations. This is fitting in a mythos in which a general disdain for the notions of the time in human culture and indeed humanity loom large. The fact that the internet is used as a portal to ‘load more madness’ and retain the longevity of the creations where ancients always return has its place in popular culture too. As Tara Brabazon states, “[p]opular culture is a conduit for popular memory, moving words, ideas ideologies and narratives through time.” (p, 67) Again, the fact that the lexicon of the Cthulu mythos is retained and recognised is fitting here.

Of course it must be acknowledged that these pop-cultural tokens exist in a wider pantheon of paratextual produce in fan culture, be it in relation to toys, models and commemorative materials and that these do not need to be science fictional or Horror inflected in order to create meaning for some and have cache. However, in Religion and Popular Culture: A Hyper-real Testament Adam Possamai makes a case that fictional religious fantasies are commonly represented in pop-cultural paratexts in for instance the Star Wars, Harry Potter and Tolkien franchises (82). He also points out that whereas many of these pop-cultural fictions work and utilize binary oppositions in relation to morality, Lovecraftian mythos stands out in that insanity and defeat is the terrible resolution (82).

In addition there is the broader canon of horror inflected paratexts circulated in this manner for an extremely long time (pop-culturally speaking) to the extent that we take them for granted (Dracula, Frankenstein etc.). In this context the wider popularization of Cthulian icons is relatively new and niche, yet persistent and growing. This is perhaps due to the curation and extension of the Mythos’ imagery by the likes of filmmakers such as Guillermo del Toro, Ridley Scott and writers such as Alan Moore who in various ways insist upon the return of the entities.

Cthulu-inspired guitar

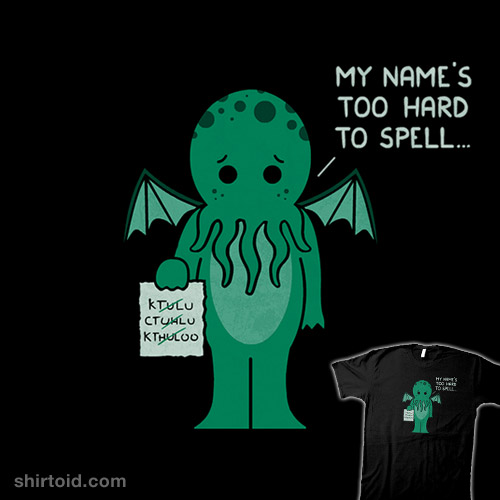

Justin Mullis points out the nature of the Cthulu mythos, with its sense of irreverence to binary structures and its polymorphous incarnations may be fitting for practices of hybridization and fan and enthusiasts ironic take on the iconic. He writes:

“Because of the heterodox themes found throughout Lovecraft's work, his Cthulhu Mythos has become a natural candidate for...subversion. Drawing on notions developed by anthropologists and historians of religion who have dealt with the related social functions of ritual, play, and joking.”

Cthulu itself as a visual presence is itself many tentacled and these can be seen as both drawing upon existing mythologies (Medusa, Hydra etc.) whist inviting myriad versions of such icons. This may sound rather far fetched, but as noted by Mullis, Lovecraft himself actively encouraged others to expand the product of his own writing including writers such as Robert Bloch. In a world of mass participatory culture, it may be strangely fitting that fans get to access these idols in a range of celebratory, ironic and humorous manners in the vein of the ever evolving mythos. Humor may be seen as derisory to the intentions of the author who is so often presented (rightly or wrongly) as impressively humorless, but these humorous takes do involve intelligence and a sense of a communal shorthand as described by Millus:

“For a joke to work, it must first create a subjunctive world in which its narrative makes sense. It is also crucial that the subject matter that constitutes the joke be recognized by those to whom it is being presented. If one does not understand what a joke is about, then it will fail.”

There is of course a precedent here in terms of textual poaching which can be seen in the form of the figurines used in the Call of Cthulu role playing game which dates back to 1981, and as anyone who has ever played desktop gaming will attest to, rituals and paraphernalia are key. RPGs exist to facilitate live fan-fictions and with these come opportunities for enthusiasts to shape narratives and to customize their own paraphernalia by, for instance, painting and customizing their collection. The term collection here is key. The miniatures in this context are collections within collectives and anyone entering a Games Workshop to see players comparing their latest addition will see that this paratextual practice is a large part of the overall immersion in whatever mythos the participants are sharing. Jenkins notes that fandom was networked through many media forms before the advent of the internet and fan communities have simply spread and evolved with changing times. There is of course a nostalgic fetishism in the case of Lovecraftian paratexts, which echoes the boom in fan-culture. This does though point to the fact that collecting and sharing binds collectives but can also become a part of an individual’s sense of self. In Cult Collectors: Nostalgia, Fandom and Collecting Popular Culture, Lincoln Geraghty writes of the ways in which material objects remind collectors of a non-digital past and their allure lies in their tactility. He writes that they are "solid signifiers of the historical significance of previous media texts." (p,2)

In this sense, collectors of memorabilia are collaborative curators of the mythos from which the items themselves arise and this may explain the proliferation in Lovecraftian creations where the ancient is ingrained and will always return. In this context, fans can become engaged with some of the original material (ironically or not) that is being shepherded along by the makers of the paratexts themselves (e,g, Pop Vinyl) and this is in many ways further bolstered by the popularization of the images and wider mythos in curatorial popular narratives as can be seen for instance in the Hellboy franchise. There is perhaps currently no more famous a curator of paratexts than Guillermo del Toro, who has an admitted obsession with genre memorabilia and is both a prolific curator and a champion of Lovecraft’s work and ethos. In 2016 there was a large travelling exhibition showcasing del Toro’s vast archive of artefacts entitled At Home with the Monsters, which of course included many Lovecraftian tokens including a life size model which glares at visitors. Speaking of his collection del Toro states:

Guillermo del Toro’s At Home with the Monsters

You want to have these icons around you and you want to have that relationship with those items because they define a moment when your soul or your spirit was touched. That is the deepest level of collecting. The more superficial level is hoarding: the anal-retentive need to have it all. (p,33)

It is of course important to consider importance of totems and other objects in the Lovecraft mythos. Many objects (keys, statues, jewelry etc.) are imbued with a terrible potency. Consider the following from Call of Cthulu:

“His name was John Raymond Legrasse, and he was by profession an Inspector of Police. With him he bore the subject of his visit, a grotesque, repulsive, and apparently very ancient stone statuette whose origin he was at a loss to determine. It must not be fancied that Inspector Legrasse had the least interest in archaeology. On the contrary, his wish for enlightenment was prompted by purely professional considerations. The statuette, idol, fetish, or whatever it was, had been captured some months before in the wooded swamps south of New Orleans during a raid on a supposed voodoo meeting; and so singular and hideous were the rites connected with it, that the police could not but realise that they had stumbled on a dark cult totally unknown to them…” (p,54)

Considering this, it may be of no surprise that the cultish and fetishistic nature of some elements of horror fandom are drawn towards attaining and maintaining these replicas in many forms, be this with irony or intricacy (or both) in mind. No doubt some will see this practice as diluting the power of the mythos, particularly in terms of the frivolous nature of some of the products. However, I would argue that in continually resurrecting such images as simulated artefacts (even in resin and vinyl) they chime, however discordantly, with the mythos itself, in that they both preserve and pervert it.

Bibliography

Brabazon, T. From Revolution to Revelation: Generation X, Popular Memory and Cultural Studies. Routledge (2005)

del Toro, G. Guillermo del Toro: At Home with the Monsters. Titan Books (2016)

Geraghty, L. Cult Collectors: Nostalgia, Fandom and Collecting Popular Culture. Routledge (2014)

Gray, J, Sandvoss, C. and Harrington, L (eds.) Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. NYU Press (2017).

Lovecraft, H.P. The Classic Horror Stories. Oxford University Press (2013)

Jones, M. ‘Tentacles and Teeth: The Lovecraftian Being in Popular Culture’ (in New Critical Essays on H.P. Lovecraft ed. David Simmons. Palgrave Macmillian (2013)

Millus, J. “Playing Games with the Great Old Ones: Ritual, Play, and Joking within the Cthulhu Mythos Fandom.” Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 26.3 (Fall, 2105) p, 512+

Possamai, A. Religion and Popular Culture: A Hyper-Real Testament. Peter Lang (2005).

Keith McDonald is