How Sound Can "Unify" Transmedia: Christy Dena on AUTHENTIC IN ALL CAPS

/Today, we are going to continue this week's focus on transmedia with the following guest post by Christy Dena. Dena's PhD dissertation transmedia really put her on the map for those of us who closely follow developments in this space. Dena is a gifted designer/theorist or theorist/designer depending on one's priorities at a given moment: someone who has a deep knowledge of the historic evolutions of theories of multimedia, intermedia, and transmedia, as she aptly demonstrates in the piece below, someone who can move between avant grade experiments and the commercial mainstream in her consideration of examples, and someone who can have a model for a transmedia design document on one page and a discussion of renaissance theories of art on the next. Transmedia has become a place which attracts artists who are also theorists, designers who are also intellectuals, and it has emerged through conversation across all of these spaces. I have come to think of Dena as someone who consistently sharpens my own thinking, since she is unafraid to critique anyone but also knows of what she speaks. You can read her PhD dissertation here.

I recently learned that she is seeking crowd funding for an exciting new project -- AUTHENTIC IN ALL CAPS -- which explores the use of sound -- including something like radio drama -- as the center piece of a transmedia franchise. It is the kind of project that needs to be done as a thought/design experiment that will help us to better understand some of the potentials of transmedia, but it is also the kind of project that it will be difficult to fund through commercial or state sponsorship. The crowd funding scheme is in its final hours and they are painfully close to meeting their goals, so I'm rushing this post out today in hopes some of you will read it, help spread the word about an interesting project, and kick in a little cash to support a worthy cause.

Here's where you can go to help Christy meet her goals.

Everything below here is Christy Dena describing -- in her own words -- the thought process that led to the development of this project. Dramatically, she wrote this on a laptop with dwindling battery juice in a house that had lost its power somewhere in Australia. Or, at least, that's the story.

HOW SOUND CAN "UNIFY" TRANSMEDIA by Christy Dena

I’d like to take the opportunity with this guest post to talk about how my research into transmedia has greatly influenced my creative project AUTHENTIC IN ALL CAPS. Here's what I like about where transmedia is moving now -- we’re seeing both practitioners and researchers take on their own approaches more and more. Not everyone is thinking the same way about transmedia. While in the past this was a sign that no-one had a clue what was going on, it is now a sign that people are making it their own. There are universals that can help newcomers understand the area, but when transmedia is under your skin, once it is a relatively unconscious activity, we start to see personal difference. This is because people are bringing their own influences and experiences to the table. We’re seeing more of themselves in their works rather than the imitative approach that is necessary when learning. So this post is about some of the influences on my transmedia thinking.

One of the criticisms of transmedia that raises it’s head every now and then is the idea that fragmentation is bad, that transmedia does away with wholeness. So during my PhD research, I trekked back to look at the notion of “dramatic unities” -- an approach to theatre that began with Aristotle and was extended later by Italian scholars. Dramatic unities includes unity of action (plot), time, and place:

Aristotle argues that tragedy must have a “unity of plot” (Aristotle 1997 [c330B.C.], 16). What this unity of plot means is that not all “incidents in one man’s life” should be included, for they “cannot be reduced to unity” (ibid.).

Unity of time, on the other hand, was introduced by Cintio Giraldi in 1554 with his Discorso sulle Comedie e sulle Tragedie publication, where he “converted Aristotle’s statement of an historical fact”—that “Tragedy endeavours, as far as possible, to confine itself to a single revolution of the sun” (Aristotle 1997 [c330B.C.], 9)—“into dramatic law’ (Spingarn 1963 [1899], 57).

And then it was Ludovico Castelvetro in his 1570 edition of Poetics, who introduced the theory of unity of place based on the idea of the unity of time (ibid., 61). It was considered proper dramatics, that a whole month of actions should not be represented (performed) in two or three hours. “This principle,” Spingarn explains, “led to the acceptance of the unity of place”: “Limit the time of the action to the time of representation, and it follows that the place of action must be limited to the place of representation” (ibid.).

As Gilbert Highet further explains, the “action of the play must seem probable,” and it “will not seem probable if the scene is constantly being changed” (Highet 1985, 143). In the end, scholarship on dramatic unities was “an attempt to strengthen and discipline the haphazard and amateurish methods of contemporary dramatists—not simply in order to copy the ancients, but in order to make drama more intense, more realistic, and more truly dramatic” (ibid.). So the notion is that a performance will be better if it has a unity of action, time, and place -- and that means focusing on small events that are linked by probability, at a certain time, and place.

Anyone who has worked on a transmedia project -- whether it be an alternate reality game or book, TV, film, and console experience -- knows that it is difficult to have your audience or players engage with all the multiple texts or touch-points you create. I remember Evan Jones observing in the early days that we could expect about 10% of our audience to continue to each touch-point. And so for some, this difficulty is in some way associated with the notion of unity. People cannot experience unity if the media texts are fragmented across time and space (and probably include many plot elements). But I’ve chosen to see this as a design challenge rather than impossibility. How can we have unity across media?

To answer this question, the other research area I looked at was “intermedia”. In 1965, Higgins introduced the term intermedia to “offer a means of ingress into works which already existed, the unfamiliarity of whose forms was such that many potential viewers, hearers, or readers were ‘turned off’ by them” (Higgins 2001 [1965], 52). It is a significant notion to discuss because its introduction coalesced a long-standing aesthetic approach, as Jack Ox and Jacques Mandelbrojt explain in their introduction to the special issue on intermedia in Leonardo: “Higgins did not invent these doings—many artists before him had achieved ‘intermediality’—but he named the phenomenon and defined it in a way that created a framework for understanding and categorizing a set or group of like-minded activities” (Ox and Mandelbrojt 2001, 47). Now, as Fluxus artist and theorist Ken Friedman explains, Higgins coined intermedia “to describe the tendency of an increasing number of the most interesting artists to cross the boundaries of recognized media or to fuse the boundaries of art with media that had not previously been considered art forms” (Friedman [1998]). Intermedia works brought together what had been artificially estranged:

Much of the best work being produced today seems to fall between media. This is no accident. The concept of the separation between media arose in the Renaissance. The idea that a painting is made of paint on canvas or that a sculpture should not be painted seems characteristic of the kind of social thought—categorizing and dividing society into nobility with its various subdivisions, untitled gentry, artisans, serfs and landless workers—which we call the feudal conception of the Great Chain of Being. […] We are approaching the dawn of a classless society, to which separation into rigid categories is absolutely irrelevant. (Higgins 2004 [1965])

The creation of works that combine conventionally separate artforms and/or media is a somewhat political as well as aesthetic act:

Thus the happening developed as an intermedium, an uncharted land that lies between collage, music and the theater. It is not governed by rules; each work determines its own medium and form according to its needs. The concept itself is better understood by what it is not, rather than what it is. Approaching it, we are pioneers again, and shall continue to be so as long as there’s plenty of elbow room and no neighbors around for a few miles. (ibid.)

Not all practices that bring together different media and artforms are intermedia though. Higgins distinguishes between mixed media and intermedia according the degree of integration. Opera is an example of mixed media for it has “music, the libretto, and the mise-en-scene” which are “quite separate: at no time is the operagoer in doubt as to whether he is seeing the mise-en-scene, the stage spectacle, hearing the music, etc.” (ibid.). On the other hand, intermedia practices involve a fusion to the degree that elements cannot be separated.

In her essay discussing her father’s theory of intermedia, Hannah Higgins reinforces this notion of fusion with her argument that intermedia “refers to structural homologies, and not additive mixtures, which would be multimedia in the sense of illustrated stories or opera, where the various media types function independently of each other” (Higgins 2002, 61). An example she cites of fusion is the blending of musical and visual techniques in Jackson Mac Low’s A Notated Vocabulary for Eve Rosenthal (1978).

It is important to note too that the distinctions from opera are, among other functions, an attempt to distance intermedia from German opera composer Richard Wagner’s “gesamtkunstwerk” or “total work of art”:

The true Drama is only conceivable as proceeding from a common urgence of every art towards the most direct appeal to a common public. In this Drama, each separate art can only bare its utmost secret to their common public through a mutual parleying with the other arts; for the purpose of each separate branch of art can only be fully attained by the reciprocal agreement and co-operation of all the branches in their common message. (Wagner 2001 [1849], 4–5, original emphasis)

The difference between Wagnerian practices and intermedia has been further articulated by Jürgen Müller (Müller 1996). Since Müller’s writings on this topic are not in English, I refer to Joki van de Poel who, in his dissertation on intermediality, discusses Müller’s argument about the difference between the “multimediality” and “intermediality”:

He makes, like Wagner, a distinction between multimedia and intermedia along the lines of the functioning of media next to each other (Nebeneinander) and with each other (Miteinander). With Nebeneinander he means that the separate media function within a larger production but maintain there own qualities, concepts and structure, whereas in the Miteinander variant the different media function in an integrative way. The media take over each others structure or concepts and are changed in this integrative process. (Poel 2005, 36, original emphasis)

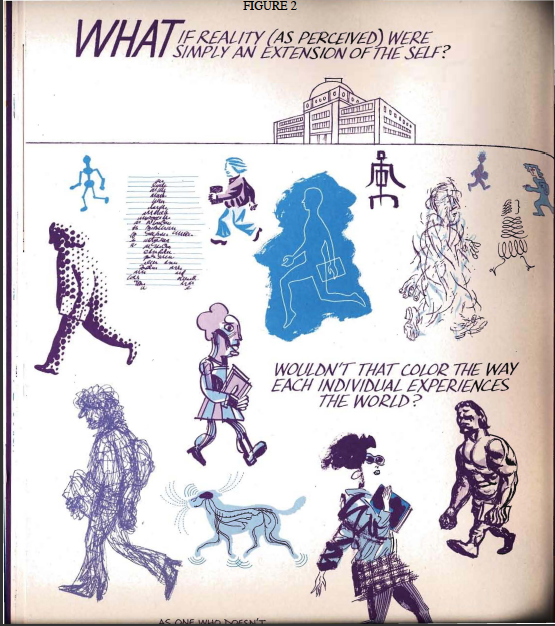

This notion of separation, or more appropriately retention of separation, is actually a key trait of transmedia projects. So what I surmised is that while transmedia projects do share a concern with bringing together media and artforms that are distinct, in transmedia projects each distinct media retains its manifest nature. Fusion does exist in transmedia projects, but it happens at an abstract level. It is characterized by a conceptual synthesis of separate media rather than an assemblage or transformation at the expressive or material level. The peculiar challenge of this approach is to bring together elements that are disparate, incompatible or isolated, in a way that retains their independent nature. This approach does not try to change that which is manifest, but tries to find connections at a level that reconfigures them conceptually. The objects change, but that change happens around the materials, within the minds of those who design and experience them. Unity is perceived, variety is manifest.

For a few years, I concentrated on this idea of abstract unity through the use of content techniques: how can we motivate activity across media with a call-to-action? What role does character and worldbuilding play in this activity? And so on. But then I had a moment when I suddenly realised there was another kind of abstract unity that can happen with media. I had also been researching simultaneous media usage or multitasking. I read novels that came with music CDs to be played at certain chapters; and read studies on what media combinations people find the most complimentary, such as having a documentary on TV when surfing the Internet. And then when I did the Da Vinci Code audio tour of The Louvre it hit me. Audio. Audio is this media element that has an intangible manifestation, it can be used in conjunction with other media and help bind them together.

I’ve since implemented that epiphany into a full-fledged creative project: a web audio adventure called AUTHENTIC IN ALL CAPS. I’m mixing together the apparently dead artform of radio drama, with web navigation and online storytelling. I’m playing with having an ensemble cast that guide players across fictional websites (multiple touch-points) with the use of humour. It is a mix of storytelling, gaming, radio drama, alternate reality gaming, and electronic literature. It is a mix of audio and vision. So we have a content and medial unity without disturbing the distinct nature of each of those websites. It is an experiment, it is exciting to me, and it is working. This is all, I guess, an example of how one can draw on research, critical reflection, theory, and practice all in one to produce something...and that something is for me both a project and an insight into how we can unify in a world of diversity.

Christy’s crowdfunding page for AUTHENTIC IN ALL CAPS: www.pozible.com/project/11529

References:

Aristotle. 1997 [c330B.C.]. Poetics. Mineola: Dover Publications.

Friedman, Ken. ([1998]). Ken Friedman’s contribution to “Fluxlist and Silence Celebrate Dick Higgins. Fluxus. http://www.fluxus.org/higgins/ken.htm (accessed Jan 26, 2008).

Higgins, Dick. 2001 [1965]. Intermedia. Leonardo 34(1): 49–54.

Higgins, Dick. 2004 [1965]. Synesthesia and Intersenses: Intermedia. UbuWeb http://www.ubu.com/papers/higgins_intermedia.html (accessed April 25, 2007).

Higgins, Hannah. 2002. Intermedial Perception or Fluxing Across the Sensory. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 8(4): 59–76.

Highet, Gilbert. 1985. The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman influences on Western Literature. New York, Oxford Univ. Press.

Müller, Jürgen E. 1996. Intermedialität. Formen modener kultureller Kommunikation. Münster: Nordus Publikationen.

Ox, Jack and Jacques Mandelbrojt. 2001. Special Section Introduction: Intersenses/Intermedia: A Theoretical Perspective. Leonardo 34(1): 47–48.

Poel, Joki van de. 2005. Opening up Worlds: Intermediality Reinterpreted. PhD diss., Universiteit Utrecht.

Spingarn, Joel Elias. 1963 [1899]. A History of Literary Criticism in the Renaissance. New York: Harbinger Books.

Wagner, Richard. 2001 [1849]. “Outlines of the Artwork of the Future,” The Artwork of the Future. In Multimedia: from Wagner to Virtual Reality, ed. Randall Packer and Ken Jordan, 3–9. New York: Norton

Christy Dena is a writer-designer who worked on global alternate reality games such as Nokia's Conspiracy for Good, Cisco's The Hunt, and ABC's Bluebird AR. She recently created a phone story for the pervasive gaming event Fresh Air Festival. Her web audio adventure for the iPad, AUTHENTIC IN ALL CAPS, was nominated for "Best Writing in a Game" at the 2012 Freeplay Independent Games Festival and is currently in production. Christy wrote her PhD on transmedia practice, and presents worldwide on transmedia writing, design, and philosophy.