EMMYS WATCH 2025 — All Dr. Robby’s Children: The Spectre of Soap Opera on The Pitt

/‘Emmys Watch 2025’ showcases critical responses to the series nominated for Outstanding Drama, Outstanding Comedy, and Outstanding Limited Series at that 77th Primetime Emmy Awards. Contributions to this theme explore critical understandings of some series nominated in these categories.

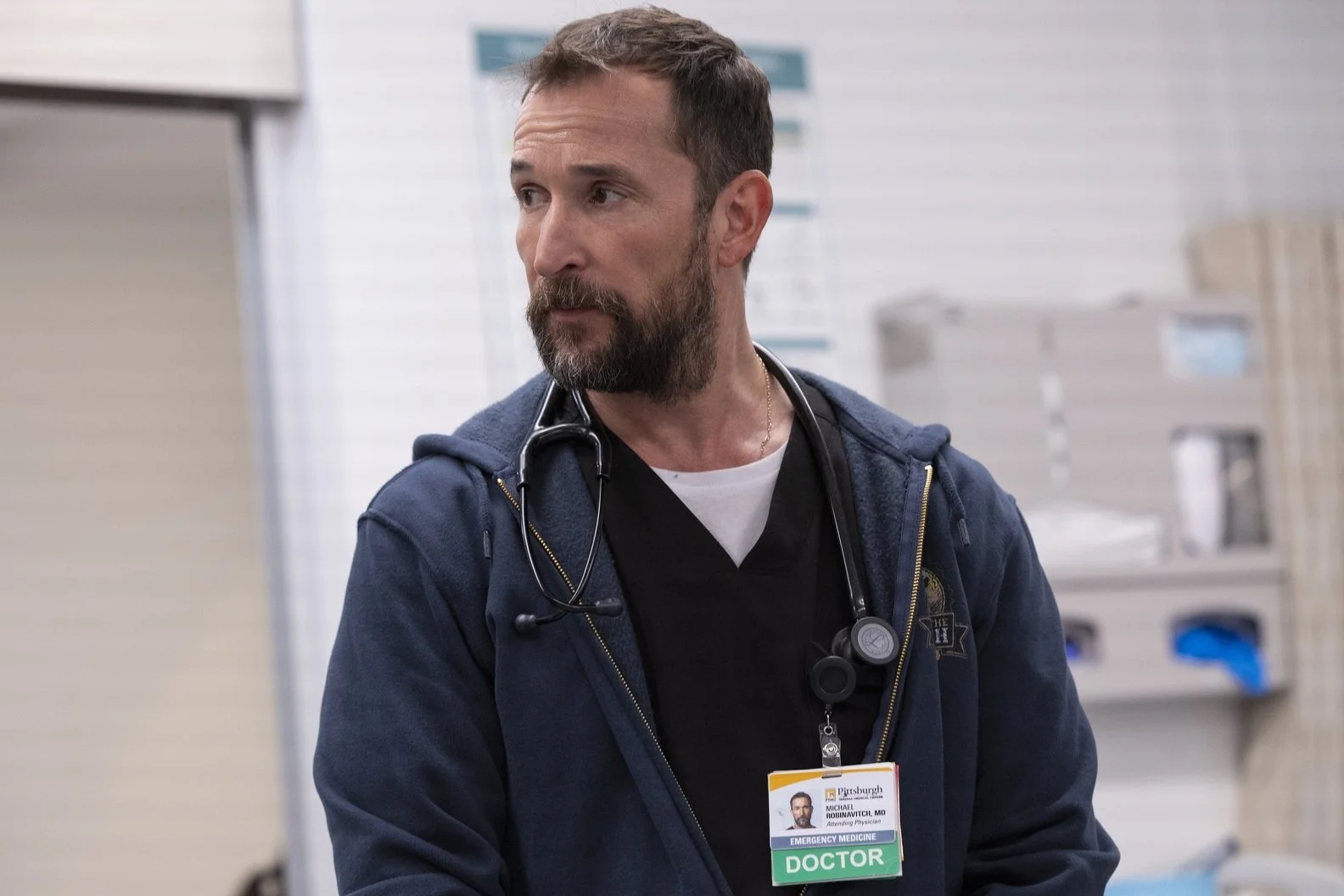

Dr. Michael Robinavitch aka Dr. Robby (Image Credit: HBO Max)

On Thursday nights in the Spring of 2025, I immersed myself in the chaos of an under-resourced emergency room in my new city of residence. Like Dr. Mel King and Dr. Dennis Whitaker, two of the interns who start their first shift in the pilot, I entered Pittsburgh Trauma Medical Center nervous but tentatively optimistic. You see, buzzy, new series on streaming platforms have let me down before. This many years into streaming originals being their own force in the television landscape, I have had my fill of television series that are really “eight-hour movies,” of scant episode orders, and of truly terrible pacing. The Pitt, however, was developed by alums of network television dramas ER (NBC, 1994-2009) and The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006). These people know TV. After mainlining the first few episodes so I could catch up to the weekly release schedule, my cautious optimism transformed into unfettered glee: We were so fucking back!

This essay, however, is not just about my love for a standout new series that will likely walk home with several gold statues come Emmys night. Rather, it’s about television form and narrative and how we collectively speak about one of the medium’s greatest forms of storytelling: the soap opera. Soap operas are characterized by multiple plot lines and a serial narrative that resists formal closure. While the setting of soap operas has changed over the years, they are frequently associated with the domestic sphere and above all with the feminine. As feminist media scholars have argued for decades, it is soap opera’s connection to the feminine that fuels the form’s cultural and critical disparagement and what makes the soap opera emblematic of television as a whole (Modleski 1982; Levine 2020). Television’s most recent cycle of legitimation, marked by cable critical darlings and punchy, single-camera comedies, were praised for being so unlike the medium they were ostensibly rising above (Newman and Levine, 2012). Praise for serialized cable and streaming dramas frequently requires the continual disavowal of the soap opera and its attendant feminized connotations. While watching The Pitt each week, I also regularly visited the series’ active Reddit community eager to engage in a virtual water cooler discussion. In post after post praising the series, viewers celebrated its distance from the soap. I had to ask myself: are we even watching the same show?

Like most medical dramas dating back to St. Elsewhere (NBC, 1982-1988), The Pitt blends episodic and serialized narrative. While some cases resolve within the span of an episode, or even within a single beat, others stretch out or are left seemingly to dangle only to be returned to at exactly the right moment. The lives of the doctors and nurses that work in the overburdened ER—Dr. McKay’s struggles with her ankle monitor and her son’s infantile father or Dr. Javadi’s tense relationship with her mother—also provide serialized threads that texture the characters and invite audience investment. Moreover, in some places The Pitt resists narrative closure altogether. Some of the figures that come into the ER leave, their cases still in limbo. (Will we ever see the victim of trafficking again?!?!) While it blends both forms, narrative threads intertwine and build on each other in a way that privileges seriality.

The Pitt’s structure, some of its aesthetic choices, and its placement on HBO Max can obscure many of its connections to the soap opera. In a tactic borrowed from the primetime network drama 24 (FOX, 2001-2010), each episode of The Pitt corresponds with one hour in the hospital workers’ shift. The season length mapping onto a shift length adheres to entrenched ideas about realism, as does many of the series’ other aesthetic choices, particularly the goriness, lighting, and sound design. In her framing of 24 as a “techno-soap,” Tara McPherson (2007) argues that the series real-time conceit and technophilia are used to distance itself from the serial’s femininity (p. 174). Beyond the “real-time” framework, The Pitt aims for a realistic portrayal of an emergency room through blood and guts, stark, fluorescent lighting, and a distinct lack of music. Greg M. Smith (2017) contends that realism, rather than being a static set of aesthetic principles or a true depiction of reality, is “an effect that occurs when our assumptions about what is ‘realistic’ intersect with the techniques that media makers use to portray their world” (p. 166). Realism, too, distances serialized dramas from the soap opera’s oft-derided excesses. Finally, HBO or Home Box Office made its name by cordoning itself off from the medium it sought to rise above (Jaramillo 2002). Critics have likened The Pitt to its 90s network parents over its prestige HBO predecessors. However, in examining its style and streaming home, it can be easy to dismiss The Pitt’s connections to feminized serials.

While I have seen and read far fewer instances of the creative team behind the show insisting that their series is above the soap or even television itself, this discourse is especially prevalent in discussions by fans in the series’ Reddit community. In a post expressing excitement after discovering the show and catching up, one Redditor stated that they thought to themselves “‘huh, solid medical drama with little no [sic] over the top soap opera bullshit?”. Further, in asking the community for other recommendations of medical shows without “soap opera bullshit” they warned commenters about daring to recommend Grey’s Anatomy (ABC, 2005-). This is a persistent thread. In another post, in which someone inquired why viewers seemed so anti-romance, the most-upvoted comment responds: “Because nobody falls in love in 12 hours. It would be melodramatic like bad level, like a soap opera.” Of course, this reply conveniently forgets that only a handful of interns are arriving for the first time alongside the viewer; most of these characters have known each other for years. Further, the show does include elements of romance (Dr. Robby and Dr. Collins are exes; Dr. Javadi tries to ask out the attractive nurse Mateo right in front of a patient who watches the scene unfold, riveted as if watching an episode of one of his series). Despite viewers expressing disdain for soap opera, The Pitt is one.

Dr. Robby and Dr. Abbott switch places as they are pushed to their breaking points at the start and close of the season. Male melodrama at its finest. (Image Credits: HBO Max)

The whole first season is a single shift; however, we do not start on just any day. In true soap opera fashion, Dr. Robby comes to work on the anniversary of his mentor’s death. Throughout the shift, Dr. Robby has several traumatic flashbacks, and his insistence on working through it leads to an emotional breakdown the writers diligently build towards. In another example, Dr. Collins is assigned to a teen girl who travelled across state lines to get the abortion pill in the same shift in which she has a miscarriage. The young girl and her aunt, who is pretending to be her mother, are attempting to terminate the pregnancy in secret. When the real mother comes to the hospital and discovers what is going on, her and her sister have a massive public fight. This is one of the many examples in which soap operatic domestic conflict anchors The Pitt despite its non-domestic setting. At the biggest scale, the season’s final episodes deal with the aftermath of a mass shooting at an outdoor concert at The University of Pittsburgh where Dr. Robby’s surrogate son Jake and his girlfriend are in attendance. Earlier beats build to these arcs, and the viewer watches as the events reverberate through the characters as they try to make it through the day. These emotional threads and heightened sense of drama are core to the series’ identity. In Reddit discussions about the identity of the shooter, viewers suggested that a range of options couldn't be possible because the show was not a soap opera. Indeed, many people said this about diametrically opposed outcomes. It seems then that soap opera came to mean anything a specific viewer thought they were above. Discussion surrounding The Pitt illustrates how “soap opera” functions as a pejorative.

Soap opera should not be an insult. In fact, I contend that The Pitt works so well because of its connection to soap opera. The television soap opera is a unique storytelling form in which narrative threads can build and build and where the viewer becomes invested in not just action but reaction, the way plot points reverberate out through the narrative and the characters and their relationships. The Pitt smartly takes that legacy and runs with it. While watching the first season, Thursday nights were once again imbued with meaning and created the space for a shared sense of community as television watchers, a feeling I had been missing since Shonda Rhimes ran Thursday nights on ABC in the 2010s. (Ironic considering how many strays her longest-running series caught when folks negatively compared it to The Pitt on social media). The Emmys invite the opportunity to grapple with the politics of taste and distinction. The soap opera is embedded throughout the contemporary television landscape. Even as many daytime serials face a grim future in networks’ scheduling, the narrative strategies and conventions of the soap opera are still on shift.

References

Jaramillo, D. (2002). The family racket: AOL, Time Warner, HBO, The Sopranos, and the construction of a quality brand. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 26(1), 59-75.

Levine, E. (2020). Her stories: Daytime soap opera and US television history. Duke University Press

McPherson, T. (2007). Techno-soap: 24, masculinity, and hybrid form. In S. Peacock (Ed.), Reading 24: TV against the clock (pp. 173-190). Palgrave Macmillan.

Modleski, T. (1982), Loving with a vengeance: Mass-produced fantasies for women. Routledge.

Newman, M. Z. & Levine, E. (2012) Legitimating television: Media convergence and cultural status. Routledge.

Smith, G. M. (2017). Realism. In L. Ouellette & J. Gray (Eds.), Keywords for media studies (pp. 166-168). New York University Press.

Biography

Jacqueline Johnson is a Teaching Assistant Professor in the Film & Media Studies Program and the Department of English at The University of Pittsburgh. Her work has been published in Communication, Culture, and Critique and The New Review of Film and Television Studies, and she is currently working on turning her dissertation on Black women and the contemporary romance genre into a monograph. When she is not teaching or writing, you can find her patiently explaining to anyone who will listen that Beyoncé is actually underrated.