Catherine D´Ignazio and Lauren Klein Interviewed by Renata Frade: The Future of Tech Feminism in the Present with Artificial Intelligence and Storytelling

/“When computers were vast systems of transistors and valves which needed to be coaxed into action, it was women who turned them on. When computers became the miniaturized circuits of silicon chips, it was women who assembled them . . . when computers were virtually real machines, women wrote the software on which they ran. And when computer was a term applied to flesh and blood workers, the bodies which composed them were female.”

― Sadie Plant, Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet

After the release of Data Feminism (2020), Catherine D´Ignazio and Lauren Klein became mandatory and acclaimed voices not only in academia but also for readers around the world. They built a solid theoretical work that brings together aspects that define a future for technological feminism. Based on data science and extensive field work, as well as associated with design, storytelling, and transmedia, the book includes several case studies of communities of women who use technology and intelligent data processing to combat violence. They also valued the work of groups who are considered minorities, such as those from the global south and Indigenous peoples.

This interview with Catherine D´Ignazio and Lauren Klein is an excellent opportunity to understand how their research developed. Knowing these contexts is highly relevant in these times of questioning the path of humanity with artificial intelligence advancements, as well as news and developments since the launch of Data Feminism. Both scholars consider storytelling crucial in their way of looking at the world, even beyond the research they develop.

Renata: When I interviewed Judy Wajcman, I asked her what would technofeminism be nowadays, if she had ever thought about updating the concept or believes it is still valid. She's been researching about artificial intelligence and the sociology of speed with more emphasis in the last years. She answered:

Technofeminism has perhaps morphed into ‘Data Feminism’. I like that term data feminism, as data science and AI are the major technological developments since I first wrote about the relationship between gender, power and technology. To me technofeminism is still a useful approach from which to extend our analysis to think about how gender is being embedded in code and software, as well as in hardware and material machinery. We have a broader sense of what technology means, such as machine learning systems and infrastructure, as well as artifacts.

Data Feminism (2020) was released two years ago but still retains freshness and vigor. It has become a mandatory source in feminist studies, technology, activism, feminist technoscience, etc. Looking back, what were the main goals achieved with the book, anticipated and unexpected? What are the main contributions—to academia and to society—of this publication?

Lauren and Catherine: First off, it’s such an honor to hear that Dr. Wajcman had such kind words to say about Data Feminism. Her work has been such an inspiration to us both! As far as your question about the goals of the book, we wrote the book above all else to show how feminism could contribute to conversations about data science and data justice. All around us we saw how data systems were being used to amplify existing inequalities rather than interrogate them, and how flawed assumptions about data and algorithms—like their being “neutral” or “objective—were leading to biased outcomes. To us it seemed that data science had so much to learn from feminism–that it really needed to learn from feminism–since feminism, and intersectional feminism in particular, has been centrally concerned with issues of inequality and the power imbalances that cause them for so long. We worked hard with our writing and with our examples to make that connection clear, and one achievement of the book which we did not necessarily anticipate is how many other people have seen what we saw, about how feminism has a central role to play in current conversations about how to envision more ethical and equitable data practices.

The other main contribution of our book, we hope, was to show that there was so much amazing work at this intersection already taking place. Folks have been working for a very long time to envision more ethical and equitable data practices, so in many cases it’s just that we need to look a little harder or a little longer for people already doing the work so that we can learn from it and raise it up. We think this lesson applies to folks in the academy as well as to society writ large. We all need to get better at recognizing our work as collective and our future as shared.

Renata: In the book, you wrote that data feminism is:

a way of thinking about data, both their uses and their limits, that is informed by direct experience, by a commitment to action, and by intersectional feminist thought. The starting point for data feminism is something that goes mostly unacknowledged in data science: power is not distributed equally in the world. (…) The work of data feminism is first to tune into how standard practices in data science serve to reinforce these existing inequalities and second to use data science to challenge and change the distribution of power. (…) Underlying data feminism is a belief in and commitment to co-liberation: the idea that oppressive systems of power harm all of us, that they undermine the quality and validity of our work, and that they hinder us from creating true and lasting social impact with data science.

You developed 7 principles for data feminism: “examine power; challenge power; elevate emotion and embodiment; rethink binaries and hierarchies; embrace pluralism; consider context; make labor visible.” Could you please cite communities and initiatives which have managed, in some way, to employ these principles since the book’s launch? What are the communities with practices you consider models of activism, communication, and engagement in this sense (cited in the book or arising from it)?

Lauren and Catherine: There have been a number of interesting communities and programs which have arisen to discuss the book or use the book. There have been at least 17 book clubs (that we know about). Some of them spawned larger initiatives. For example, the Data Feminism Network was started by a group of students in Canada as a book club and then went on to run podcasts, book clubs about other books related to gender & data, mixers and more. The nonprofit Data-Pop Alliance has started a program in Data Feminism where they use the principles to help organizations address SDG #5: to “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”. Another nonprofit, the Civic Software Foundation, founded a program based on principle #6 about context. The technology think tank Pollicy, based in Kampala, Uganda, used data feminism to develop a report about Afrofeminist Data Futures. In the Latin American context, groups like DataGénero and Feminicidio Uruguay are discussing starting a Latin American data feminism network. There have been two standalone conferences about data feminism (one in Spain and one in Denmark).

We have been thrilled to see these book clubs, discussions, reports and programs arise across a range of disciplines, geographies, and age groups. When possible we try to support these groups, connect them to each other, and show up for Q&As.

Renata: Ruha Benjamin (2022) said in her latest book:

Viral Justice grows out of my contention that viruses are not our ultimate foe. In the same way that COVID-19 kills, so too ableism, racism, sexism, classism, and colonialism work to eliminate unwanted people. Ours is a eugenicist society: from the funding of school districts to the triaging of patients, 'privilege' is a euphemism for tyranny. (…) Viral Justice offers a vision of change that requires each of us to individually confront how we participate in unjust systems, even when ´in theory´ we stand for justice. Whether you're the explicit target or not, inequality makes us all sick. (…) But viral justice is not a new academic theory or a novel organizing strategy, nor does it name a newfangled phenomenon. Instead, it is an orientation, a way of looking at, or looking again at (i.e., respecting), all the ways people are working, little by little, day by day, to combat unjust systems and build alternatives to the oppressive status quo . Viral justice orients us differently toward small-scale, often localized, actions. It invites us to witness how an idea or action that sprouts in one place may be adopted, adapted, and diffused elsewhere. But it also counters the assumption that ‘scaling up’ should always be the goal.

In a way, Benjamin invites readers to have courage and enthusiasm not only for fighting for a more egalitarian, fair, diverse and supportive world, but for imagining it and building what we wish for. This brought me to civic imagination (Jenkins et al, 2020):

the capacity to imagine alternatives to current cultural, social, political, or economic conditions; one cannot change the world without imagining what a better world might look like. (…) The civic imagination requires and is realized through the ability to imagine the process of change, to see oneself as a civic agent capable of making change, to feel solidarity with others whose perspectives and experiences are different than one's own, to join a larger collective with shared interests, and to bring imaginative dimensions to real-world spaces and places.

D´Ignazio (2016) applied civic imagination concept in a very original way, a case study on the MIT campus. I would like to know how it would be possible for a person or a community to develop a sense of civic imagination when we are talking about data and numbers, something so markedly quantitative? You mentioned that behind numbers there are stories and narratives. What would be good practices, or case studies that you consider important, which relate storytelling with data in activism?

Catherine: Yes - I have always loved the concept of the civic imagination and I definitely think it can be applied to working with data. Because first of all, not all data are quantitative. For us, data are information that are collected in a systematic way. So this could certainly be numbers, readings from a sensor or income levels by census block, let's say. But this could equally be oral responses to a questionnaire (so qualitative data) or images, drawings or art. Data also do not have to describe only what "is" already in existence. For example the Paper Monuments project by Monument Lab asked residents to draw new proposals for monuments they would like to see in their neighborhood. This is definitely a project where narratives and stories and art were interwoven with data, indeed each paper monument became an entry in the larger dataset. And this is also a project where data can come from the future – i.e. from visions of the future generated by residents and everyday people. Another project that interweaves storytelling, data and civic imagination (and that Lauren and I admire a great deal) is COVID Black, led by Kim Gallon, who’s now at Brown, from Purdue University. COVID Black not only gathers and publishes Black health data, but it also does trainings and produces data stories, visualizations and other public interpretations to combat racial health inequities (and also to push back against the relentless, racialized deficit narratives depicted by the mainstream media). They state "Data is more than facts and statistics. Black health data represents life." Both of these projects produce data, analyze data, and visualize data in the service of larger goals around sparking civic dialogue, challenging stigmatizing narratives, and working towards social justice.

Renata: In Data Feminism and also in D'Ignazio's upcoming book from MIT Press, Counting Feminicide: Data Feminism in Action, communities and collective expressions are fundamental for changes in the status quo against prejudice, racism, and various expressions of violence, especially in the global south axis, in Latin America.

Political and social awareness is a consequence of plural and broad access to information. Today, data consumption is concentrated on Big Tech digital platforms. In addition to issues arising from the HCI, the importance of producing inclusive and participatory design on platforms for collectives, there is a crucial issue that many communities face, precisely because most of them run on volunteer work: the difficulty of executing communication plans, whose activities are concentrated, many times, in special actions such as campaign launches and commemorative dates.

According to Dahlgren & Hill (2023), “media engagement as an energizing internal force that propels citizens to participate in society. (…) Furthermore, we distinguish engagement from participation: we see engagement as a subjective prerequisite for participation – which we in turn treat as observable action, the fulfillment of engagement.”

What would be the elements that could awaken in citizens involved with data feminism or femicide an engagement beyond the occasional participation in causes like this? Do you believe that a transmedia plan could be an assertive path?

Catherine: One place to direct our attention in relation to this question is the work of Helena Suárez Val. She has almost completed her doctoral program, and her dissertation examines engagement and participation in feminicide data that circulate on Twitter. She is asking what kinds of emotional and affective impacts participation on social media has in relation to the issue of feminicide. You'll be able to see her thesis later this year - it is titled "Caring, With Data: An Exploration of the Affective Politicality of Feminicide Data."

And one of the things our research team found in the Data Against Feminicide project is that many of the feminicide data producers – the activist groups who painstakingly register gender-related killings – are not only working to create counts and statistics but are also working to craft narratives and reframe debates around the issue. While most media attention focuses on women's murders as isolated events perpetrated by pathological actors (the "jealous" ex-husband, etc) feminicide activists use aggregated data to support the feminist argument that feminicide is a structural and systemic and preventable form of violence. They use data to move feminicide from a personal or domestic issue to a political or public issue. I called this theme "reframing" and discuss it at length in Chapter 6 of Counting Feminicide, and it especially applies for groups who are coming to this work through data journalism and communications.

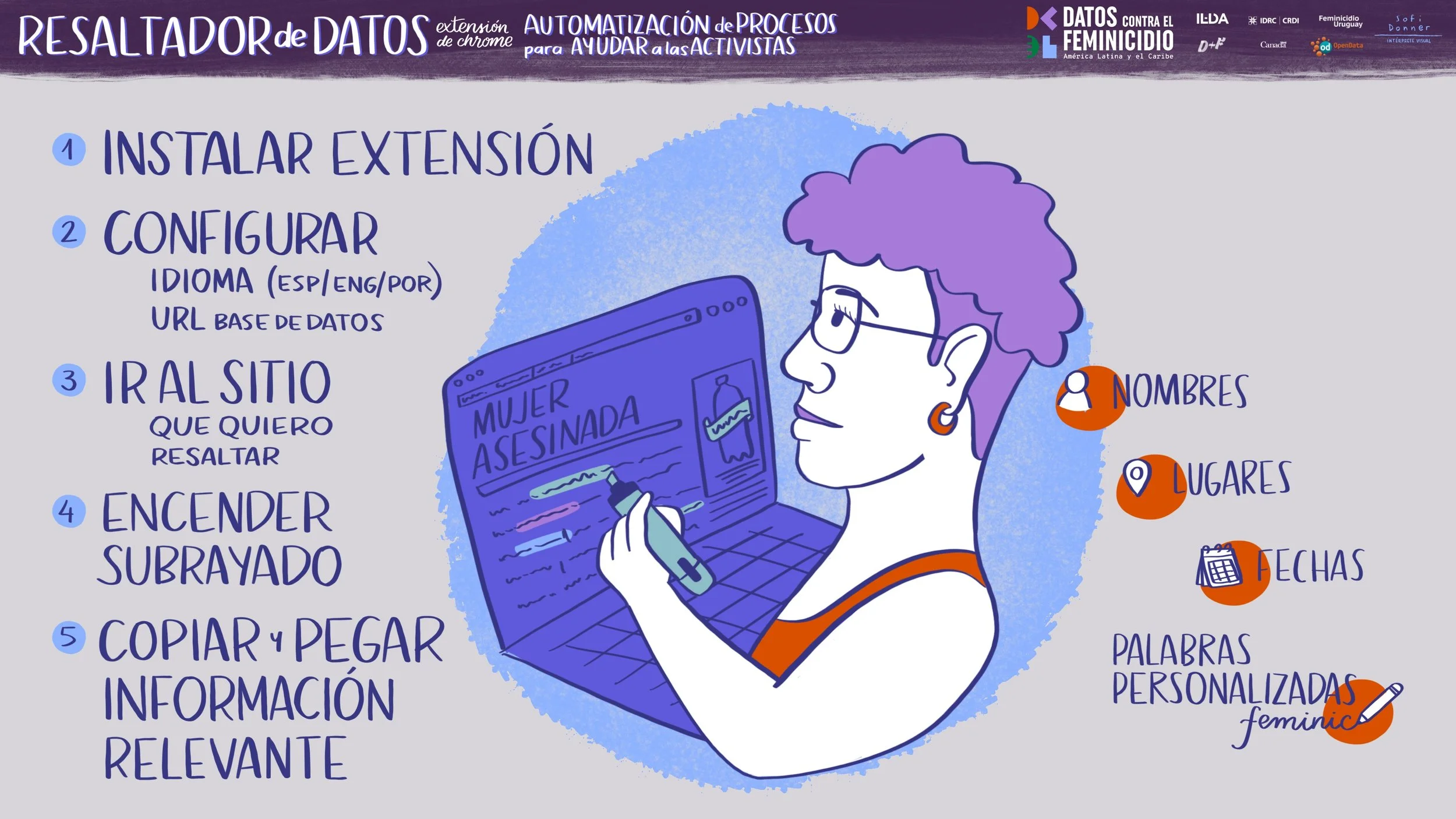

FIGURE 1: Graphic recording by Sofi Donner about tools co-created by the Data + Feminism Lab with data activists to monitor feminicide

I think many data activist groups could benefit from learning about the ideas of transmedia storytelling and transmedia planning. From what I've observed in the Data Against Feminicide project, many groups are already employing transmedia storytelling without explicit knowledge of these theories or ideas. They develop highly creative ways to circulate their data across multiple digital platforms, also in public spaces, and often using compelling and vibrant visuals and narratives to support their numbers and statistics. Much of this work is also about memorialization – about not forgetting the people lost to structural violence and about seeking justice for them and their families.

Renata: Lauren, I see that you also have a new project coming out with MIT Press on the history of data visualization. How does this connect to Data Feminism and the work that you did there”?

Lauren: Yes, I am finishing up a project with my own research group called Data By Design: An Interactive History of Data Visualization. It tells the story of the emergence of modern data visualization in a way that shows how questions of ethics and justice have been present in the field since its start. One of the things that we tried hard to convey in Data Feminism is how all of these technologies–data science, data journalism, data activism–they all have long histories, and those histories influence the tools we have to use in the present as well as how we think to design new ones. These histories are not always good ones. In a US context, for example, the history of data is inseparable from the histories of slavery, colonialism, and capitalism. This does not mean that we should not use data or data science, but it does mean that we need to know about those histories so that we can be on alert for the ways that they might inadvertently influence the work we do in the present. The same thing is true for data visualization, so I’m trying to tell that story in a way that makes it clear and compelling and necessary for visualization designers today.

FIGURE 2: A news article and visualization examining where Christopher Columbus is commemorated in the heritage landscape along with where his presence is being contested. By Youjin Shin, Nick Kirkpatrick, Catherine D’Ignazio and Wonyoung So for the Washington Post.

Another aspect of that project that is connected to the work that Catherine and I did in Data Feminism is how it looks to women, to Indigenous folks, to Black folks, to folks on the margins, for historical examples of work using data and data visualization to challenge unequal power structures. Interestingly, many of these historical figures understood their work as multimodal and functioning not too dissimilarly from how Dr. Jenkins describes transmedia storytelling. You could think of W.E.B. Du Bois, or someone who I spend a lot of time talking about, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody–they understood their data visualizations as only part of the story, and were very explicit about how their images created meaning only when considered alongside writing and lived experience. There’s probably something in there about how the experience of being reduced to a datapoint, which is very common among marginalized folks, teaches you that the full story can only be gained by communicating across (and at times against) different media forms.

FIGURE 3: A screenshot of the homepage-in-progress for Data by Design: An Interactive History of Data Visualization. Project team: Lauren Klein, Tanvi Sharma, Jay Varner, Nicholas Yang, Dan Jutan, Jianing Fu, Anna Mola, Zhou Fang, Shiyao Li, Margy Adams, and Yag Li.

Renata: How do you see the present and future of feminism? I know it's a very broad question, but what is the perspective between losses and gains today and in the coming years in academia, society, and companies?

Lauren and Catherine: This question has become timely in more ways than we could have ever known. With the Dobbs decision and all of these anti-trans bills coming up through the states, we have suffered major losses, so as a society we need feminism now more than ever. And that clear need for feminism is a gain. With that said, we need to be very very careful to ensure that the feminism of the future is an inclusive one, that a renewed attention to child-bearing bodies doesn’t come at the expense of trans exclusion. We all deserve autonomy over our bodies, and some work we as feminists can do is to help everyone–in society as well as in academia and industry–see how reproductive justice and trans justice are both struggles for autonomy, and those struggles are interconnected.

Lauren: One other hope for the feminism of the future is that it will become more transnational, and in particular, that the (perceived) dominance of US feminist movements–at least from our perspective here in the US–might become a little shaken up. We have so much to learn from Latin American feminist movements in places like Argentina, for example, which were ultimately successful in re-establishing abortion rights. Theirs was a struggle that began out of an anti-feminicide movement, grew to encompass reproductive rights, and per my comment above now includes issues relating to transgender justice. These activists recognized that their values and goals were aligned with each other, and that they would be more powerful if they allied themselves with each other. The broad lesson of solidarity is one that’s always helpful to re-hear.

Renata: In Data Feminism, Catherine presented it as follows:

I am a hacker mama. I spent fifteen years as a freelance software developer and experimental artist, now professor, working on projects ranging from serendipitous news-recommendation systems to countercartography to civic data literacy to making breast pumps not suck. I'm here writing this book because, for one, the hype around big data and AI is deafeningly male and white and technoheroic and the time is now to reframe that world with a feminist lens. The second reason I'm here is that my recent experience running a large, equity-focused hackathon taught me just how much people like me—basically, well-meaning liberal white people—are part of the problem in struggling for social justice.

And Lauren:

I often describe myself as a professional nerd. I worked in software development before going to grad school to study English, with a particular focus on early American literature and culture. (Early means very early—like, the eighteenth century.) As a professor at an engineering school, I now work on research projects that translate this history into contemporary contexts. For instance, I'm writing a book about the history of data visualization, employing machine-learning techniques to analyze abolitionist newspapers, and designing a haptic recreation of a hundred-year-old visualization scheme that looks like a quilt. Through projects like these, I show how the rise of the concept of “data” (which, as it turns out, really took off in the eighteenth century) is closely connected to the rise of our current concepts of gender and race.

The trajectories of you both are special and inspiring. Therefore, I would like to know:

What advice do you have for academics and people who would like to work in areas similar to yours? Or for a world view, how to start having a more plural, diverse, fair view and to put this into practice? What were your main inspirations in life? What is the importance of storytelling in your life?

Catherine: My main inspirations in life were books and stories. As a shy kid, I would retreat to reading, books, and hanging out with my cat in a tree making up my own stories. I had a powerful role model in my father who is a writer and was also a technologist and early proponent of computers as creative and educational tools. One of the things I feel that I learned from him is that when you love seemingly unrelated things, you can bring them together. He did that in the form of creative educational technology at a time when computers were seen as tools for business and accounting. For me, the disparate things were software development and art and feminism. But it did take time to figure out how to join these interests. For a time, I had three separate careers as an independent artist, a freelance software developer and an adjunct professor. This was completely untenable after having kids and needing a steady paycheck, so I ended up struggling for some years trying to figure out a path forward. I was eventually able to find that path in academia. While definitely not perfect, there is a lot of intellectual and creative freedom you have as an academic. My advice for people is to take care of your own and your family's health and basic needs first – this is like the stable base from which you can be a creative person in the world – and then work on joining your seemingly disparate interests and values into a new path forward in the world. It is possible and the results will be beautiful.

Lauren: I love that! My advice is connected to Catherine’s, which is that it’s OK if your path is not a direct one, and that it’s totally fine (and, honestly, probably better) to permit yourself to follow each twist and turn. (I wish I’d given myself that permission when I was feeling lost). I also think the most interesting and impactful work comes from people who bring their own disparate interests together, and who have a range of experiences in the world. If you’re able (and I recognize that this isn’t an option for everyone) try to spend time in different environments and connect with different kinds of people. A broader and more inclusive world view begins with exposure and understanding.

FIGURE 4: Lauren in the classroom at Emory University. Her co-taught course on Data Justice brings together perspectives from the humanities, the social sciences, and the natural sciences, about the promise and pitfalls of data and AI. Photo by Kay Hinton.

As far as storytelling, that’s a large part of how I see my current work. I research things that matter to me and then use storytelling to try to make them matter to others. I spent a lot of time thinking about narrative and structure and style and, simply put, how to tell a good story. Stories are how we learn about–and learn to care about–lives and experiences that we can’t directly access. I feel so privileged that this is the kind of work I get to do.

Biography

Renata Frade is a tech feminism PhD candidate at the Universidade de Aveiro (DigiMedia/DeCa). Cátedra Oscar Sala/ Instituto de Estudos Avançados/Universidade de São Paulo Artificial Intelligence researcher. Journalist (B.A. in Social Communication from PUC-Rio University) and M.A. in Literature from UERJ. Henry Jenkins´ transmedia alumni and attendee at M.I.T., Rede Globo TV and Nave school events/courses. Speaker, activist, community manager, professor and content producer on women in tech, diversity, inclusion and transmedia since 2010 (such as Gartner international symposium, Girls in Tech Brazil, Mídia Ninja, Digitalks, MobileTime etc). Published in 13 academic and fiction books (poetry and short stories). Renata Frade is interested in Literature, Activism, Feminism, Civic Imagination, Technology, Digital Humanities, Ciberculture, HCI.

Catherine D´Ignazio is an Associate Professor of Urban Science and Planning in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT. She is also Director of the Data + Feminism Lab which uses data and computational methods to work towards gender and racial justice.

Lauren Klein is Winship Distinguished Research Professor and Associate Professor in the Departments of English and Quantitative Theory & Methods at Emory University, where she also directs the Digital Humanities Lab. She previously taught in the School of Literature, Media, and Communication at Georgia Tech.