Feeding the Civic Imagination (Part One): Intercultural Food

/The Civic Imagination Project team spent a lot of time during the pandemic thinking about food (and making food) from our own pods and considering the ways that communities get forged, identities get defined, around what we eat and what food we share with others. Out of those discussions has come a special issue of the cultural studies journal, Lateral, focused on “Feeding the Civic Imagination” still in process and scheduled to release in the months ahead. To celebrate and extend the rich mix of formal academic essays there, we invited some of the would-be contributors to participate in a series of dialogues at the intersection of their research. I am going to share these rich and thoughtful conversations over the next three installments. These conversations were overseen by Do Own “Donna” Kim, who was recently award a doctorate in communication from the University of Southern California and accepted a job at the University of Illinois - Chicago. Sangita Shresthova, my longtime research collaborator, has also taken the lead here. The rest of the editorial team consists of Essence Wilson, Isabel Delano, Khaliah Reed, Becky Pham, Javier Rivera, Steven Proudfoot, Amanda Lee, Molly Frizzell, Paulina Lanz

Elaine Almeida and Lisa Silvestri

SILVESTRI: Hi Elaine! I am excited to talk food, justice, and civic culture with you! Maybe we could start with a little “definition of terms.” I roll my eyes at my own suggestion because it sounds very academic of me to say and perhaps indicates that I'm in the process of reading seminar papers..!

I guess it makes sense to start with what makes this conversation series unique: FOOD! For me, “food” is a medium of sorts. But I realize that it can also be artifact, ritual, and/or practice. How do you understand food?

ALMEIDA: First, I have to say as an avid lover of food, what an honor it is to be able to study and be with it in our scholarship! I’ve come to thoroughly enjoy studying and thinking through food for many reasons— like you said, food can be a site of ritual and practice, and what’s more, food elicits deep ties to memory and our psychic lives. Food invokes memory through its visceral employment of the sensorium, creating neural pathways not just related to taste, but to texture, smell, sight and sound of food. So there’s something to be said about food’s role in building our memories and imaginaries of the world.

But more so, I think through food particularly through the lens of Rachel Slocum’s food justice, where she understands that food is a benign but charged site for construction of race and ethnic relations. Food is a cultural contact zone where we have the opportunity to not just experience another culture through sight and sound, but literally process it through our body—the food stays with us, is, for a moment, us. It is a site where one can really undertake an embodied understanding of the ways a people create, imbibe and nourish themselves through the world around them. It, however, often a site of othering; not ritual or practice, but the literal devourment of our imagined ideas of how others can make us more whole, more full. Instead of using food to understand and imagine others, food, and particularly “ethnic” food in the United States serves as a place where people can imagine more about themselves as cosmopolitan, “adventurous” subjects without ever having to make true connection with the purveyors and creators of their food. This is what Slocum means by food being a benign but charged space. If everytime we taste a meal it elicits a memory of us devouring the other, how do we imagine ethical, people-centered relationships to food, particularly for marginalized groups in America who are visually underrepresented, but are readily represented in the takeaway menus and trendy cafes?

And you know, in my project (jeez sorry to ramble!) I take this question to examine how Thai Americans are represented in food journalism in our contemporary era. Thai food is a popular takeaway option and “fusion” food in the United States, but Thai Americans are a generally small minority group in the United States and are not often represented across various media— including, as I soon found out, even in journalism about Thai food. Articles about Thai recipes and restaurants were centered on how Thai food might attract American readers and never centered Thai Americans. Mark Padoongpat, author of Flavors of Empire: Food and the Making of Thai America, argues “Thai food acted primarily as a site for the construction of Thai Americans as an exotic racialized foriegn other through taste and other human senses besides sight.” And so again, and again, I come back to this idea of how can we imagine people-centered relationships to food that move from devouring to nourishing each other?

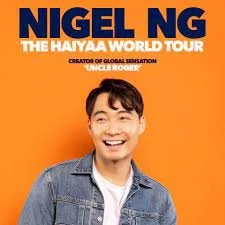

SILVESTRI: I like that- “from devouring to nourishing.” I also hear what you are saying about food being a “cultural contact zone” but also a potentially dangerous site for Othering. It’s that idea of a little knowledge has the potential to produce a lot of (wilful) ignorance. The work you describe reminds me a little of the comic, Nigel Ng and his podcast “Rice to Meet You” where among other things he problematizes (in a funny way) this kind of teflon cosmopolitanism you describe; Where a hunger for exotic/forieng/other is satiated through safe/controlled exposure but nothing actually *sticks* in a meaningful way.

ALMEIDA: No, totally, you exactly understand this difference between devourment and nourishment, this radical ability to create using our relationships and food as a vehicle!

SILVESTRI: I guess the food story I have for you is more about absence; the problem of not having food as a point of contact. If food is a useful point of entry (even if problematic), what about cultures with no shelf space in our pantry? How do they exist in our civic imagination?

The case study I am working with involves a partnership between US Veterans and Afghan farmers. First, a little background: In the 1960s and 1970s, Afghanistan’s export of raisins accounted for 60 percent of the world market. So for a time you might think, “Ah Afghanistan, yes I’ve had their dried fruit.” But after decades of war in that country (first with the Soviet Invasion then with the U.S.), they have been cut off from global trade. Instead rhetorical associations with terrorism dominate American ideas about Afghanistan.

Case study research from 2004 includes an interview with a raisin trader named Mazar who said: “We don’t have any government and they don’t care about the raisin business. The custom and excise authorities are serious about their own benefits and are not serious about trade. They collect duty from us, and that’s all.” The farmer’s remarks speak to an inability to participate in and subsequent exclusion from the global community. To that I would add, without Afghanistan's identity represented through food commodities, it is much easier to ignore, forget, and Other the people of Afghanistan in the civic imaginary.

ALMEIDA: You know, when we talk about civic imagination so many examples are visual and auditory, and I think what both of our stories show is that a robust imagination, one that can really help us articulate alternative paths forward, needs to encompass numerous senses and be a full bodied imagining. Right? Because our stories seem to have opposite problems that are leading to the same absence—Afghan people are represented in mass media but not in intimate cultural spaces such as food and spices, while Thai food and spices are present throughout the US, but Thai people are missing from the public eye. With both, we have an unfinished idea of who either people group authentically are. To imagine ethical, caring relationships for public good, we have to imagine the robustness of life in unmediated ways. Food allows us to physically come in contact with items and artifacts meaningful to different ways of life. And isn’t the crux of this that part of the work of the civic imagination is to debate and work through narratives, hopes and fears, but again, both of our projects are centered on people groups who are both widely understood through only one narrative and lens.

For Thai Americans, the easy “so what” is representation, right? That people should know that Thai Americans are a robust ethnic group in the United States. But more than that, how can imagining Thai Americans and Thai people help us to understand the history and implications of US-Thai relationships—where Thai subjects/objects are always sites for others pleasure (be it the Thai tourism industry, sex industry or even again, Thai food,)— and actively create equitable, ethical relationships? And I wonder for you, what does access to Afghan food products help us to reach or reimagine? (Which wow, not a large question at all!)

SILVESTRI: Ha! That’s great- the bigger the questions, the better the conversation! I like what you said “food allows us to physically come in contact with items and artifacts meaningful to different ways of life.” That’s the heart of it. And the sensory nature of food- you are right- is paramount to its role in imagination. I am sure we all have a taste, smell, or texture that transports us in time and space, even back to our own childhood. But of course that transportation or I should say imagination hinges on familiarity. When the food or spice is unfamiliar- foreign- Other- it is more difficult to imagine.

The rest of the story about Afghanistan picks back up during the U.S. war in that country when a soldier who knew just a little Dari (the local language) worked with an Afghan saffron farmer to get his spice to market. The farmer’s request implied an interest in transporting his spice locally, but three Army Veterans had bigger ideas. Now, Rumi Spice as it is called, sources crocus flowers from local Afghan farms and employs hundreds of women in the cultural tradition of hand-harvesting the flowers’ delicate stigmas (the source of saffron). It’s so cool. And now- from the one farmer’s request–Rumi Spice sells Afghan saffron (and wild black cumin too) in American stores like Whole Foods and those Blue Apron boxes that people become obsessed with during the pandemic! How cool is that? I think the thing that blew me away when I learned this story is not only the imagination, but also the courage and faith it took to do something like this. It’s one thing to imagine but it is another to execute. Imagination, though, has to come first.

ALMEIDA: Yes! And I think what food helps us to add to our civic imagination is methods of imagining and transforming. A lot of the time, our imagination can be pretty ocularcentric—we need to “visualize” or “picture” the things we want. I fall into this trap a lot. And because we’ve started with “visualizing” and “picturing” solutions, we operate in a way to match: we fight for representation, to be seen, we fight for exposure, for visibility. And this is such a limited way to bring about justice. To be clear it is an important way, but not the only way. Because then we get caught upkeeping the artifact of the image we’ve created, and not on the processes of life. Joan Tronto, the care ethicist, reminds us that care is not simply a thing or a collection of things to uphold, but a continual collaborative practice we cultivate in ourselves and others to strengthen democracy.

And to circle back to my opening little thought, what food brings to care, imagination, justice is those methods of practice. If we’ll all indulge my craziness for a second, here’s a recipe for Khao mok gai, a Thai saffron chicken dish: https://hot-thai-kitchen.com/kao-mok-gai/

One, super delicious, but two, what do we see happening in this recipe? We understand that there are numerous pieces happening together, but at slightly different times, that will come together in the end to make the dish. The chicken has to marinate for at least two hours, and that is only after you’ve used a mortar and pestle to make the marinade. Meanwhile, for the dipping sauce, you just have to bring the ingredients together and blend, easy-peesy. The rice has to be sauteed on a high heat and then fluff over a low heat. It has to go through the different heats and from the wok to the pot to get to the fluffy tasty place it needs to be. And right, this isn’t the whole recipe, but what we see is that to come together to make this dish, one that brings comfort and nourishment, numerous rates and style of change need to take place all dependent on not only the ingredients, but how each product simmers, or marinates or cooks into our new dish.

And notably, while I use this food example, I want to be super mindful about multicultural examples that have used food—the “melting pot” or the “stew” or “salad bar” of America. While those food examples were useful for promoting a specific style of colorblind multiculturalism in the US, that’s not what I am interested in. This Thai saffron chicken dish is coming out yellow; the rice, chicken and spices are all being transformed before us, not just made visible next to each other.

And cooking takes time. It is something we have to do more or less everyday to sustain our bodies, unless someone else does it for us, and then their labor has helped alleviate mine. There are questions of sourcing and presentation and all of these things are directly applicable to how social change takes place on micro and macro scales. We always talk about how “sweet” things can be, but how can we imagine how savory and spicy justice will be on our tongues? For me, this is the exciting potential of food and why our communication and stories about food are not just trivial fluff pieces, but really cue us in on processes of change.

SILVESTRI: You are so fun to talk to. I love how you engage metaphors to guide your thinking (and I’m thankful for the recipe!). I had the same thought about the problems associated with “melting pot” multiculturalism and a concern that my own talking about the civic imaginary slipped into the white imaginary as I spoke about the importance of exposure (“Exposure to whom?” my better angels asked). And as dissatisfied as I am with mere exposure, I wonder if we could briefly celebrate exposure as a step on the justice continuum. I am thinking of the dreaded “ethnic aisle” in every American supermarket.

As you know, most of my scholarship is about war in some capacity. And war, like it or not, brings a lot of societal change. The typical focus is on how war advances communication technologies, but it’s also worth recognizing what war has done to our supermarkets. When US troops returned from Vietnam, for example, they had a hankering for South Vietnamese food. American supermarkets expanded their “specialty aisles,” which consisted mostly of Italian food products at the time (thanks to WWII), to include other items like rice vermicelli or glass noodles. Now our supermarket “ethnic” aisles consist of a nonsensical smattering of other “foreign” food products. Meanwhile Italian products have made their way out of the “ethnic aisle.” Olive oil can now be found with other cooking oils..

So I guess what I am thinking about as we apply cooking metaphors is to what extent is exposure a flash in the pan form of justice that would do well to stew for a while? I liked your line about care being a “continual collaborative practice” because it made me think about adaptation. My favorite part of cooking is the artfulness of adaptation. I am terrible about following recipes. I never have all the ingredients. I am a vegetarian. I like spicy things. I add. I eliminate. I taste. I adapt. And as I do, the food becomes an expression of who I am. So when I go to the “ethnic aisle” to buy plantain chips I am not looking for something exotic. I am looking for “my chips.” And when they slide across the checkout counter and the cashier says “huh, I’ve never seen these before '' and I say “they’re good with hummus,” I feel like something important is happening. I am tapping into the civic imagination. In that moment, the cashier and I glimpse ourselves as “part of a larger democratic culture.”

Almeida: Your art of adaptation that in the process brings others with you—wow! I love that so much. We’ve talked about so much in this piece— a plethora of big ideas that intersect our lives and our work—and again and again, what I take away from you is this stubborn optimism that engaging the civic imagination with others through food, through stories, that this has the potential to disrupt in ways many take for granted. You make me want to return to my work with new senses!

Lisa Silvestri is Associate Professor of Communication Studies at Gonzaga University. Her writing showcases creative ways people exert agency in even the most stringent circumstances. One of her areas of focus is the way social media links communication to connection, which helps produce and sustain individual and collective identities. Her book Friended at the Front won the 2016 James W. Carey Media Research Award for pioneering cultural approaches to the study of social media. In 2017 she received a major grant from The National Endowment for the Humanities in support of her community-based initiative, Telling War, which helped surface and inspire Veteran voices through a variety of story forms. She has written, lectured for, and had her research featured in several popular outlets including The Washington Post, The New York Times, The South by Southwest Festival, and The 92nd Street Y.

Elaine Almeida is a Mass Communication doctoral student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison with minors in Gender and Women’s Studies and Transdisciplinary Visual Cultures. She is a qualitative scholar interested in how minoritarian storytellers utilize care to transform digital spaces. Previously she attended the University of Texas at Austin for both a B.S. and M.A. in Advertising. She further explores her interests through her role as a freelance digital artist.