Agents of Influence: An Educational Video Game to Fight Misinformation

/Over the past few years, I have been offering advice to Anahita Dalma and a team of USC students (among others) who have been working on a game, Agents of Influence, intended to address current issues around misinformation and disinformation circulation on social networking platforms. The group is launching a Kickstarter campaign as of today to help raise money to push the project to the next level. Having been impressed by their original insights into games-based learning and media literacy, not to mention their professionalism, I want to give them a chance to share some of their work here.

Agents of Influence: An Educational Video Game to Fight Misinformation

Written by: Michael Warker

Over the last year, we all have had to live much of our lives on the internet, whether it be through work, play, or reading the latest updates on these tumultuous times. With the convenience of the internet comes risks, however, as misinformation can easily masquerade as verified fact, and this threat inspired us at Alterea Inc. to think of a way to help.

The solution we came up with is Agents of Influence: a spy-themed, educational video game that uses active inoculation theory to prepare students to recognize and combat digital misinformation. This theory is much like an inoculation for a virus, as it posits that exposing students to manipulative argumentation strategies makes them more resistant to subsequent manipulation attempts. Through Agents of Influence, we are aiming to equip a generation of “digital natives” in middle school with the tools and knowledge they need to combat digital misinformation.

Agents of Influence was created around the belief that video games have the capacity to be extremely useful learning tools. We constantly abided by teaching best practices to make sure our game was fulfilling the goals we wanted. Video games are a fantastic tool, as demonstrated by the idea of mastery orientations, which states that true knowledge comes from a desire for learning and understanding, not from a letter grade. Through the fun of video games, students actually want to learn. Studies have also shown that feedback is most helpful when it is “specific” and “immediate”, which is easy to accomplish through the video game format.

As we researched our game and made connections with teachers, librarians, government officials, and more, we realized that misinformation may be one of the greatest threats facing our generation. During the 2016 election, it was found that the top “fake news” stories outperformed the top real ones on Facebook. Even more troubling, an Ipsos poll showed that 75% of Americans who see fake news view it as “somewhat” or “very” accurate. Since the 2016 election, the world has faced many huge issues that require credible information to combat them, including an ongoing global pandemic. We need tools to fight back against the growing threat of misinformation.

The “truth decay” caused by misinformation has taken hold of the world during the digital age, eroding civil discourse, causing political paralysis, and leading to public uncertainty and disengagement. With so much noise, people are taking the easy route of simply reaffirming their own biases with the information that they consume. The most recent and prevalent of these issues lies in COVID-19 vaccine trust, with many people on both sides of the issue finding information that simply reaffirms their own beliefs, as opposed to engaging in civil conversation with each other.

These are all immense issues, but the solution lies in every individual’s ability and, more importantly, their willingness, to investigate the information that they consume. To encourage our target audience of middle schoolers to become more engaged and critical of what they see online, we knew that we had to make it fun for them. This reason is why we decided to make a video game to teach them about misinformation.

Before thinking about the fun, however, we had to determine what we were trying to teach our middle schoolers. We spoke to multiple experts on media literacy, and we investigated how other organizations such as MediaWise, News Literacy Project, and more are educating people about misinformation. From all of this research, we derived three core learning objectives that have guided our game.

Agents of Influence will teach students how to:

1) Question the trustworthiness of information.

2) Investigate the trustworthiness of information.

3) Use this investigation to inform their decisions and build better information consumption habits.

If students walk away from this game questioning information they consume, and they have the ability and drive to research to verify their information, then we will qualify Agents of Influence as a success. For added benefit, however, we have also included much more educational content.

We’ve designed our game around many educational standards, including Common Core, CASEL SEL, NAMLE, ISTE, Learning for Justice Digital Literacy Framework, Media Smarts, California Model School Library Standards, and NCSS C3 Framework. A process which is common to many of these standards is the IRAC, or the Inquiry, Research, Analysis, and Conclusion model. The IRAC model was formative to both our story structure and our game structure during the creation of Agents of Influence. Once we finished our initial education prep, we tackled the hard part: making it entertaining for middle schoolers.

We discovered that the IRAC model forms well into a mystery story structure, so we decided to make our spy-themed game center around an investigation that students will have to lead. Every one of our three core modules will involve a plot from an evil spy group led by the nefarious Harbinger, and the player will have to work together with their spy team, the Agents of Influence, to stop them before it’s too late. These three modules are centered around cyber danger, political disinformation, and pseudoscience, respectively, so even the theming of each story is tied into our core learning objectives.

Creating a compelling narrative was an essential step in the development of this game, as it has been shown that emotional resonance helps students better retain information. We’re creating an experience that will teach students to question information, which is a new skill, not just information to be regurgitated on a test, so having a narrative that helps them remember the significance of their actions both online and in the real world is essential to a successful game In addition to our compelling narrative,we developed four mini-games centered around our other learning objectives.

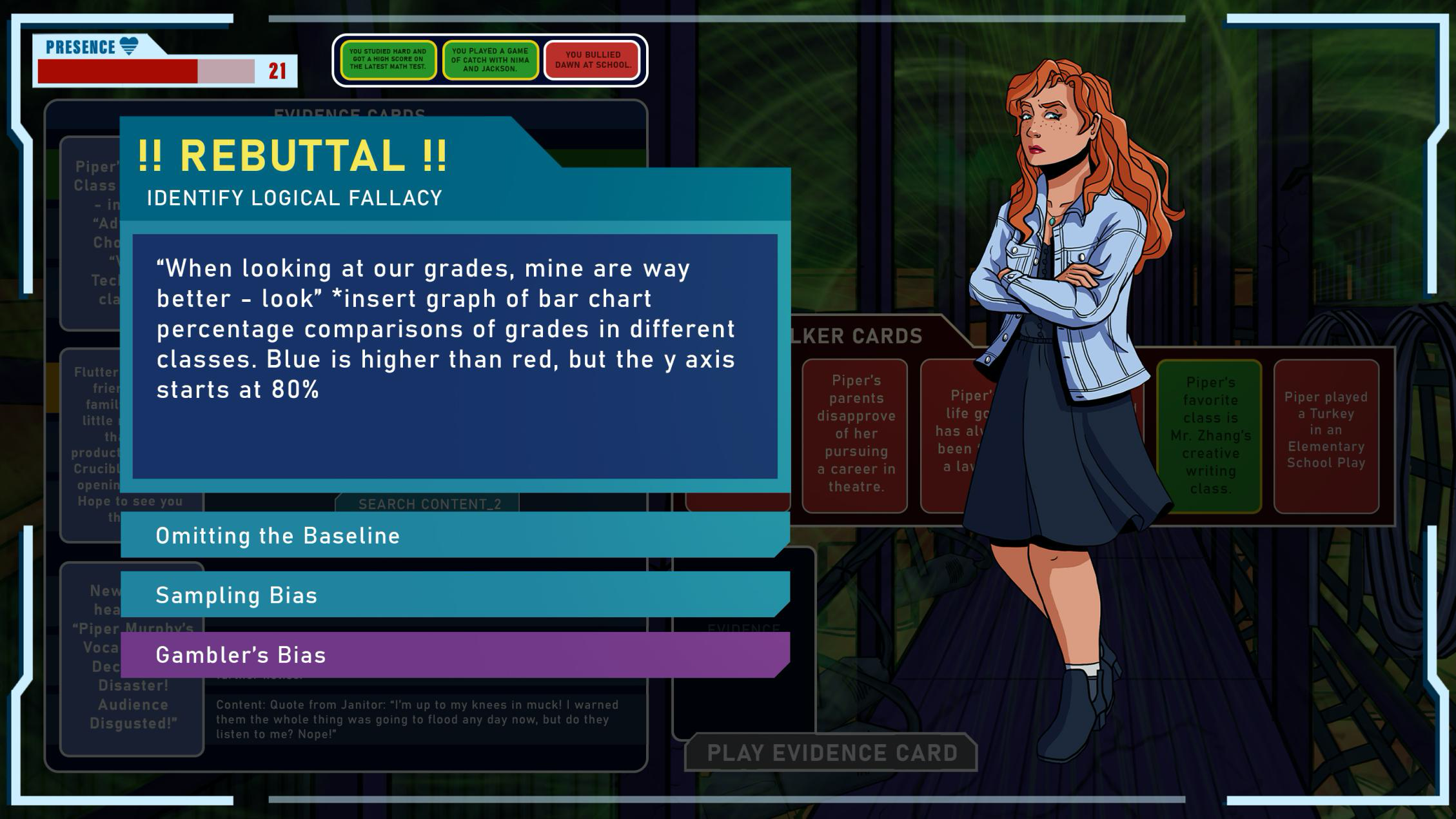

Conversation: Disguised in the narrative context of an interrogation, students must use good conversation practices to talk to a suspect. Every turn, students choose between different dialogue options, putting them in control of how they talk and act. If they’re not careful, however, they could trigger a negative “state,” such as making their suspect defensive or suspicious of them. These negative states are triggered when a student says something aggressive, critical, contemptuous, or alienating to their suspect. In addition, this game also teaches students how to recognize logical fallacies that may arise in arguments so they can better combat these fallacies in their daily lives.

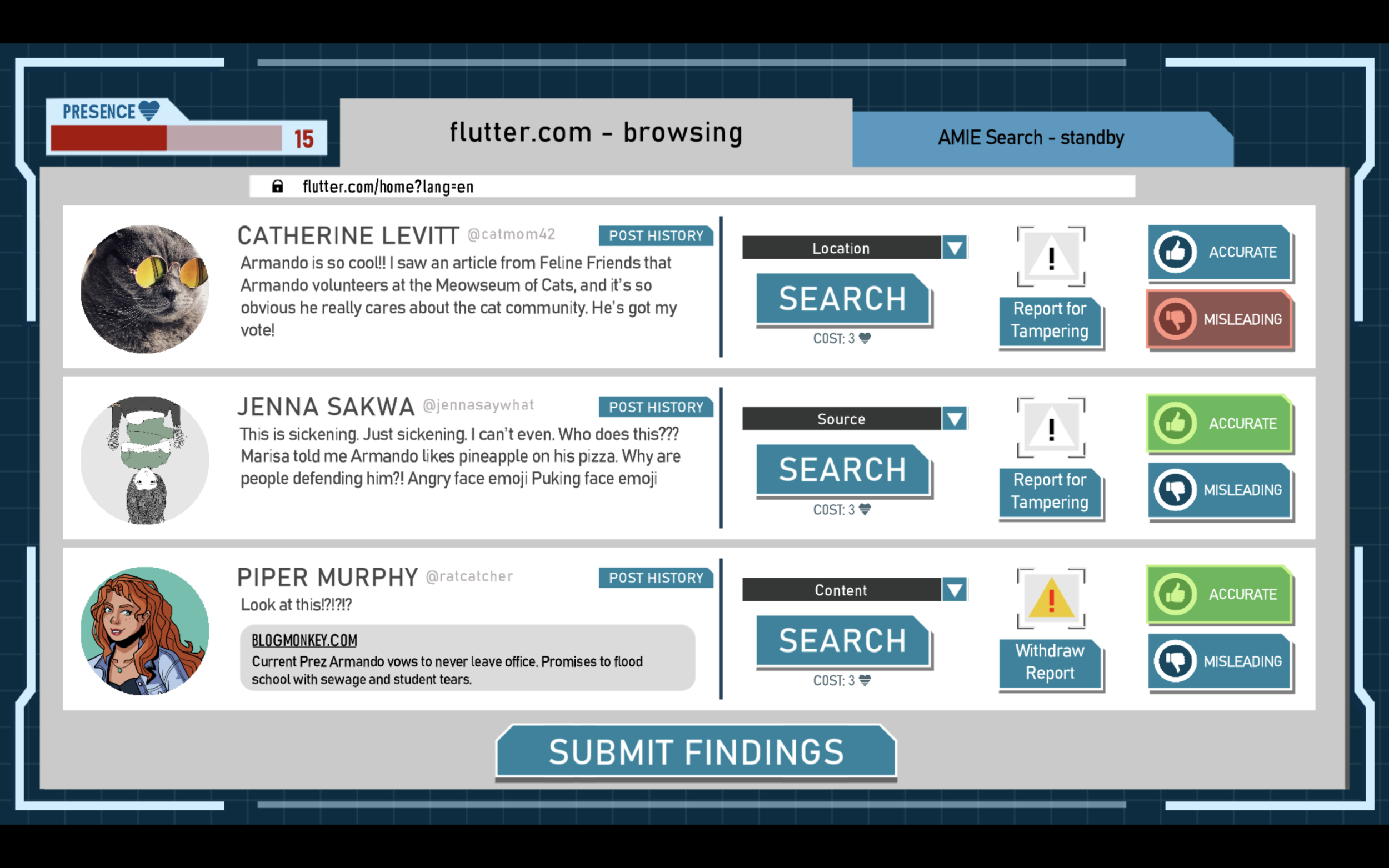

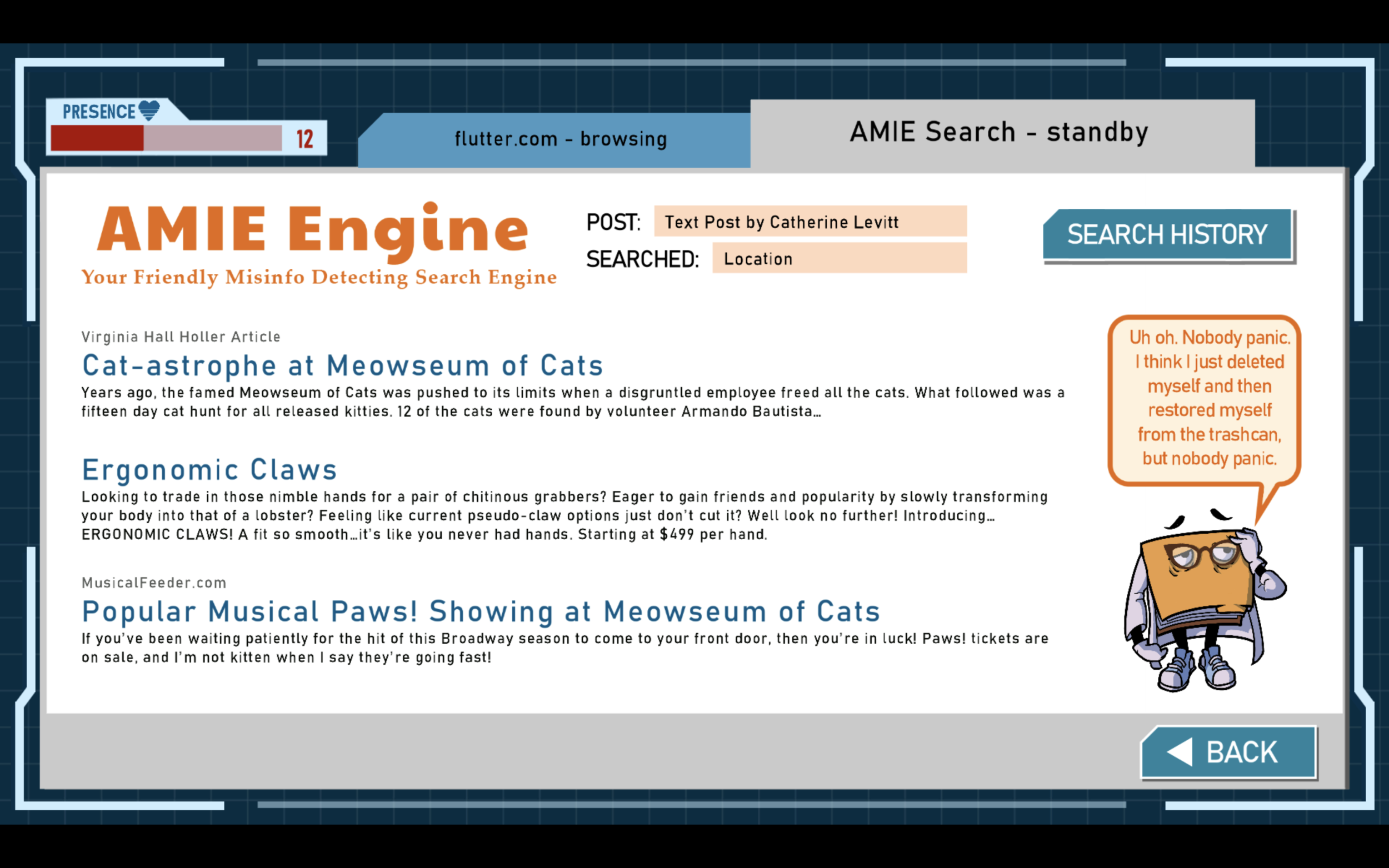

Research: This game takes place in the all too familiar landscape of a social media feed. Setting the game on social media allows for high transferability of skills, as this is where students would most likely encounter misinformation in their own lives. In our research game, students must flag posts as “accurate” or “misleading” by researching the post’s content in a simulated search engine. They’re also taught lateral reading techniques, along with learning about different misinformation types such as satire, false context, imposter content, and fact versus opinion.

Analysis: Your artificial intelligence friend, A.M.I.E. is malfunctioning, and you have to prove to her that you’re a master of misinformation by answering her questions. Visually, we have a maze representation of A.M.I.E.’s circuitry, which students can navigate if they correctly answer analytical questions about an article they read. Students answer true and false questions about the purpose of the article, the bias of the author, logical and data fallacies the article employs, and many other relevant skills useful to critical reading.

Finale: This last game is the emotional and intellectual climax of every module of Agents of Influence. Players must save a fellow student who has had their memories corrupted by misinformation. Through research and critical thinking, the player must remind their classmate who they truly are and save them from the clutches of misinformation.

Of course, we did not know whether our game would be fun for a middle schooler until we sat down over Zoom with a few of them and heard what they had to say. After playing our research game, a small pool of middle schoolers we tested all said that they would research more. This was after only one version of the game in an early paper prototype. Stacking this exposure along with our other games and our narrative could have a huge potential impact on students. Plus, to top it all off, our testers all had fun and were engaged with the material. One of them even asked if we could make the game for his Nintendo DS so that he could take it on the go.

In addition to these small tests with middle schoolers, we brought in teachers and other experts to playtest our games so that we could learn more from industry professionals about how to enhance Agents of Influence. We also sent out multiple surveys to teachers around the world to learn how to make our game seamlessly accomplish their various classroom needs. Through this research, we learned that designing with ample flexibility was essential, which is why we decided to separate the game into smaller, thirty minute sections that are individually playable. This structure allows for teachers to focus on skills that are most applicable to their classrooms. This feedback, along with the copious other guidance from experts we consulted, has been essential in forming the structure and content of our game.

While our initial tests were small, they have allowed us to prepare our framework for feedback, which will be instrumental in our expanded testing period in the near future. Some of our core questions include asking if players have the motivation to look for multiple perspectives when researching after playing our games. We also want to know if they feel better empowered to fight misinformation online after playing Agents of Influence. So far, our takeaways are solid, but expanded testing will be necessary to verify our information.

To truly see if our game is effective in preparing students for the looming threat of misinformation, we need additional funding. Going forward, we hope to fund our first module, Agents of Influence: Cyber Danger, and we want thousands of students to play it for our in-depth beta period. We have worked hard to ensure this large-scale test will show similarly enthusiastic results as our initial tests.

Agents of Influence was created wholly to fit the needs of our educational objectives. Story, character, and gamified elements all arose from the core need to teach students how to better combat misinformation, and we are very excited to get Agents of Influence in front of even more students and teachers in the future. This game has a long road ahead of it, and if you would like to follow that journey, try our prototype, or learn more about the game, please visit our kickstarter or our website for more information.

Michael Warker is a recent graduate of the University of Southern California where he studied Theatre and Screenwriting. He is writing on behalf of Alterea, Inc., which is a story-telling company focused on immersive story-living that lets participants grow and change through the stories they experience. This article was written in association with Anahita Dalmia and Jasper McEvoy. Visit our website here: https://www.altereainc.com/