Endings, Beginnings, Transitions: Star Wars in the Disney Era (Part 3 of 3) by Will Brooker and William Proctor

/Proctor

The finale of The Mandalorian dropped about one week after the release of The Rise of Skywalker: what are your views on the show now it’s finished its first season?

Brooker

The Mandalorian is straightforward, sometimes corny, with a couple of minor plot holes in each episode, but I also find it thrilling, witty and surprisingly moving, with a very strong sense of character development considering that the protagonist almost never removes his helmet. I was struck, in the finale, by how much I was drawn into and won over by the brief dialogue between two Biker Scouts, who are never named, never previously introduced, and who simply sit around on their vehicles killing time, bickering and delaying the moment when they return to base to face the series villain, Moff Gideon.

The dialogue is banal, everyday stuff, but as they shoot the breeze we gain a strong sense of these two guys, who aren’t committed to the Empire but were just doing a dull job in a quiet outpost until the episode’s action started, and their relationship. It’s Waiting For Godot or Rosencrantz and Guildenstern meets the 1997 fan film Troops, and it gives us a rare insight into the life of an average trooper, who usually just provides cannon fodder for the heroes. There’s a lovely, if obvious, visual gag where they both try to shoot a nearby can with their blasters, and assume their guns aren’t working when they repeatedly miss -- it’s a long term fan joke that Stormtroopers are terrible shots -- and because they don’t take their helmets off, the actors convey character and mood through slightly-exaggerated shrugs, head tilts and nods. I was more fascinated by those two bikers than by many of the named minor characters in The Rise of Skywalker, and it really brought home the difference between the two for me. I was bored through much of the most recent Star Wars movie’s two hours and twenty-two minutes, because I just didn’t feel invested or engaged. The Mandalorian shows it’s possible to draw viewers fully into characters and their situation within a short TV episode; within a five minute scene, even.

It’s undeniable that The Mandalorian provides fan service itself, and here I think it’s easier to pin down who it’s appealing to: Yoda, Mos Eisley, IG droids, Biker Scouts, even Mandalorians are all from the Original Trilogy. But the Troop Transporter I mentioned above had previously featured in the animated series Rebels, and the new weapon revealed in the finale’s final moments, the Darksaber, was also previously seen in both Clone Wars and Rebels, with this appearance marking its entry into live-action canon. So The Mandalorian also pays respectful tribute to the previous Star Wars TV shows, as well as to the first trilogy of films. I think it judges its approach almost perfectly, balancing nostalgic name-checks and throwbacks with twists and innovations: exactly what I would have wanted the sequels to do.

Proctor

I’m not certain how I feel about the finale right now. In the main, I remain happily ambivalent. It was fine, better than I expected, and it was quite funny to see and hear the Biker Scouts shooting the breeze in the scene you discussed (and failing to shoot the can is certainly a slice of fan service, as if we’re all in on a private joke about Stormtroopers being terrible shots). I didn’t like Giancarlo Esposito’s character, Moff Gideon—I couldn’t help but think about his role as Gus in Breaking Bad! I like the fact that we finally learned the Mandalorian’s name—Din Djarin—and that the next part of his mission to protect the foundling will be to scour the galaxy to find his home-world. There are some world-building opportunities there. Although I was pleased with the weekly release schedule for the series, I want to go back and rewatch it all in two or three gulps. I have heard that someone online has edited the series into a six-hour movie. That’s an interesting idea.

Interestingly, the budget for The Mandalorian was $100 million, which I thought seemed high for a live-action TV series. Comparatively, Star Trek: Discovery cost $120 million for fifteen episodes, and includes huge space battles, lavish set designs, and higher production values than any Star Trek series before it, although I think the series suffers from the same blight that the Star Wars sequels did—a fantastic spectacle marred by severe canonical breaches, and poor storytelling.

If we take the sequel trilogy combined, the production budget works out at approximately $900 million for seven-and-a-half hours of Star Wars cinema. Now I recognize that blockbuster films in the Star Wars vein need to make much more profit than streaming platforms like Disney+, but I wonder if budgets have to be so extravagant considering that The Mandalorian is relatively low-key, but still manages to be stronger in story-telling than any of the sequels. With Blumhouse Studios currently attracting a higher return-on-investment with their ‘micro-budget’ model than any blockbuster of recent years, it may be high-time for the bigger players to consider what should be more important: story or spectacle (if they can’t seem to do both together). Remember that Blade Runner 2049 was deemed a catastrophic commercial failure because it only made $150 million, even though it was mostly a critical triumph. If TROS doesn’t at least match up with the box office haul of The Last Jedi, which was almost half what Avengers: Endgame managed, I bet it will be considered a failure too. Perhaps the entertainment-industrial complex should consider if the largest budgets are actually converted into bigger profits. Consider Todd Phillips’ Joker, a film made for $60 million yet still managed to exceed the billion dollar watermark. (For my money, Joker is a far superior film than Avengers: Endgame, but if box office receipts are anything to go by, I’m probably in the minority on that one.)

I’m sure my thoughts on both The Mandalorian and the Star Wars films in the Disney-era will continue to shift, but for the moment, I’m quite glad that there will be no more movies for a while. And that saddens me.

To finish, I’d like to conduct an experiment, if I may. While searching my hard-drive, I came across the interview I conducted with you almost immediately following the Lucasfilm acquisition in 2012. So let me take you back in time to meet your former self. It’s quite brief, so I’ll include both questions and answers (for posterity, if nothing else). Professor Brooker meet Dr Brooker!

——————————

Q. As a 'Star Wars' fan, how do you feel about the news? i.e excited? indifferent? cautious but optimistic?

A. I would say a combination of the three. I am only really a fan of classic Star Wars, and I am not even sure if I include ROTJ in that. What Star Wars has become, as a franchise, now leaves me cold and disconnected, so in that respect, I am indifferent -- I don't think there is anything left to ruin or spoil that Lucas hasn't already done, and I don't feel much sense of investment, loyalty or protectiveness about the franchise anymore.

However, as a fan of the OT, what I always really wanted to see, when I was 12, was a continuation of the first trilogy -- not prequels at all. So in that respect, something about this announcement touches my inner 12 year old (in a good way).

At first, my reaction was that this would run the franchise even further into the ground, but now I'm feeling that it couldn't get worse, and could actually be rescued.

Q. What would you like to see happen here? i.e storylines, actors, etc?

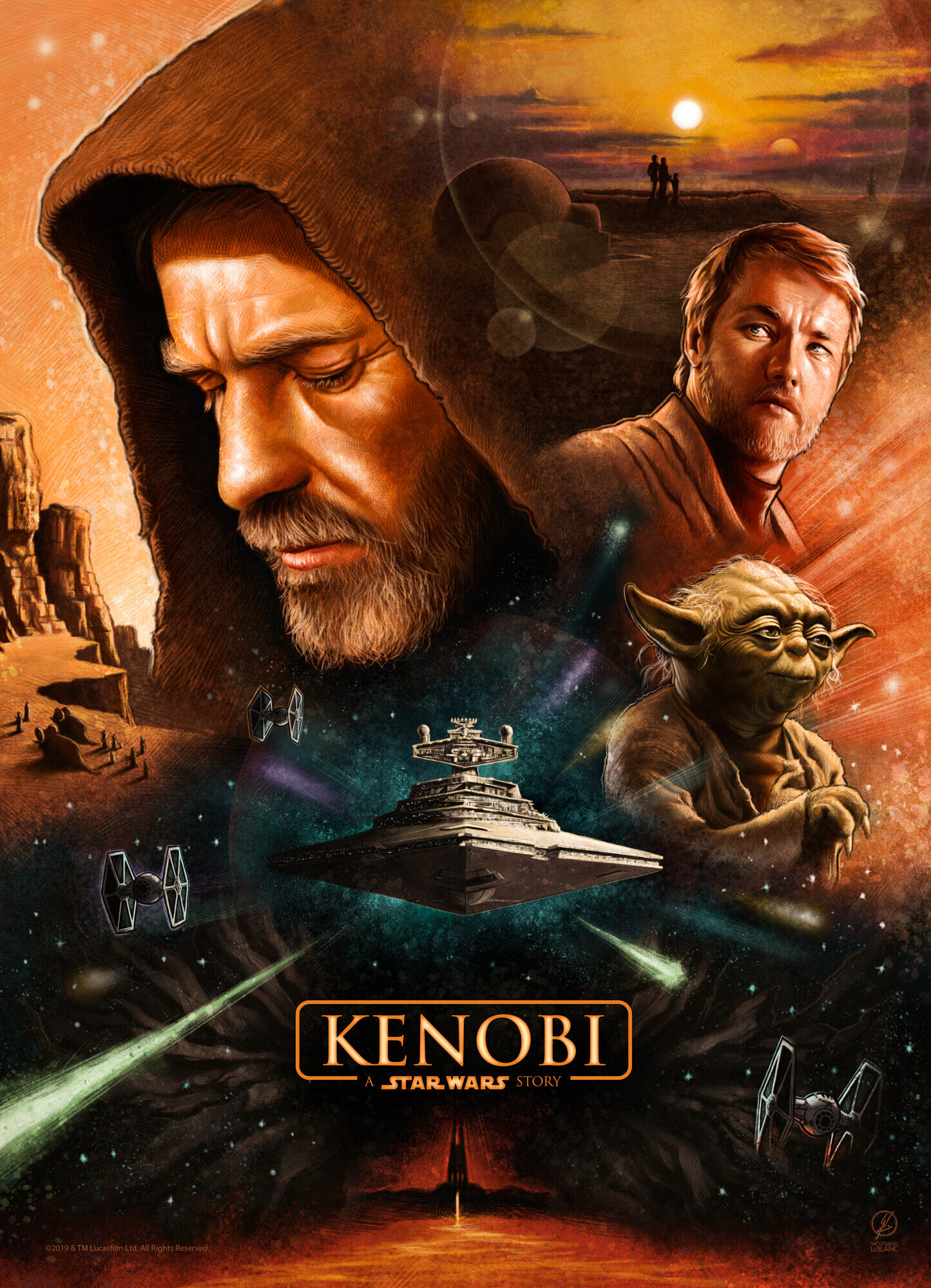

A. Nathan Fillion as Han Solo. I think he was essentially playing ESB-period Han in Firefly and Serenity, and this would be a perfect choice -- far more perfect than Ewan McGregor as Obi- Wan, for instance.

It would have the resonance of Brandon Routh's tribute to Christopher Reeve in Superman Returns, and Zachary Quinto playing Nimoy's 'Spock' in Star Trek.

In terms of storylines, I think there is a great deal of promising territory to be explored. The overthrow of an empire does not happen in the blink of an eye. Many civilisations that were colonised by the Empire would resist the new Republic regime and see them as an unwelcome, invading, colonising force. In a galaxy-wide empire, there would be multiple pockets of Imperial resistance (which would in turn be a form of new rebellion) -- all the stormtroopers and officers wouldn't surrender at once, across the entire galaxy.

Moreover, we know there is a substantial third strand of gangster culture in the SW galaxy -- the Hutts would not simply accept the new republic on Tatooine. Han Solo didn't even believe in the Jedi -- there is a huge network of smugglers, administrators, spice miners and businessmen who don't care about the Jedi/Sith conflict, and aren't going to take kindly to a new regime, however benevolent it feels it is. And with only one Jedi around, it's not as if the new republic has a ready-made police force as it did in the old days.

Q. Who would you like to see involved on a creative level? [i.e, director, writer etc].

A. Joss Whedon. He would actually be my new hope.

Brooker

I imagine I was singling out Joss Whedon in 2012 because of Firefly, which I was clearly very taken with. I think his most recent movie project was the disastrous Justice League, so I don’t think I have quite that much investment in him any more. However, everything else I said seven years ago sounds pretty solid to me. Obviously, the sequels chose a very different direction, using the original cast and setting the action thirty years in the future, whereas I proposed recasting and exploring the galaxy soon after the end of Return of the Jedi. What’s most striking to me is that I describe a scenario where the Empire has broken down into stubborn outposts and resistance groups, fierce in their loyalty to the old order; where most characters have no reason to believe in the Force; where the New Republic has failed to establish itself convincingly, and where we focus on smugglers, miners, criminals and petty officials doing business in the aftermath of galactic conflict. If you replaced my suggestion of the Hutts with the Bounty Hunters’ Guild, I was almost pitching The Mandalorian there.

On a purely personal level, when I think back further to what I dreamed of in 1983 and what I would have told you I wanted from a Star Wars sequel once Return of the Jedi was over, I’m saddened to consider how far removed the actual films are from what I imagined. To an extent that is because of the simple length of time between 1983 and the present day; if Ford, Fisher and Hamill had agreed to shoot a new trilogy in 1987, for instance, we might have had something closer to my ideal. And of course, I’m very different now from the person I was in 1983.

This is not to begrudge anyone else’s enjoyment, but when I consider that gulf between what I wanted, as a teenage Star Wars fan, and what we got, a significant part of me would have rather seen no sequels than the messy trilogy that’s just finished, with its uneven continuity and very mixed critical reception. If we were able to send Episodes VII, VIII and IX back for me to watch in 1983, I think I’d be dismayed by them.

That is, again, an entirely personal, very narrow and subjective response to the films, and I’m not suggesting that anyone else should agree with me; but I think it’s a valid response from the perspective of someone who was an absolutely devoted fan from 1977-1983, kept the faith during the lean years of EU novels during the 1990s, and in the 2000s, wrote two books about the franchise. Looking back, I think it will be difficult not to judge both the prequel and sequel trilogies as deeply flawed projects, both of which should arguably, with hindsight, never have been undertaken.

Kylo Ren argues in The Last Jedi that Rey should ‘let the past die.’ Increasingly I find myself feeling that we should let the past be, and that despite the merits of the six movies that added to the Skywalker saga, I might have just preferred to imagine what happened before and afterwards.

Proctor

I realise that readers may believe we are the academic equivalent of Statler and Waldorf from The Muppet Show, but I’m reminded of something I read as an undergraduate that I’ve kept close to my heart. In a chapter titled ‘The Culture That Sticks to Your Skin: A Manifesto for a New Cultural Studies’ by Henry Jenkins, Tara McPherson, and Jane Shattuc, the authors write that ‘we confront that popular culture with a profound ambivalence, our pleasures tempered by a volatile mixture of fears, disappointments, and disgust.’ And in Jenkins’ seminal Textual Poachers, he argues that ‘fandom is born out of a mixture of fascination and frustration.’ As Original Trilogy Star Wars fans, I think we’re quite frustrated with the direction the sequel trilogy went in, but remain fascinated by the potential of what the franchise could be, if managed by the right creative people. We are absolutely being subjective, and of course we would use more objective language for academic outputs; but I don’t think we’re saying anything that hasn’t been said by other fans (although quite what the term ‘fan’ means nowadays is more amorphous than it has ever been, I believe—a conversation for another day!).

When the Disney acquisition was first announced, I was quite excited. I’m all for more Star Wars movies, truth be told. I think we both love popular culture, but that love doesn’t come without conditions, and without criticism. Personally, I’m not overjoyed that audiences have enjoyed the Disney Star Wars films as that would surely mean we will get more badly constructed stories—and story must remain the boss, as Stephen King once put it. There’s no stronger feedback than box office receipts, and if TROS manages to, say, overtake The Force Awakens’ commercial dividends, which isn’t looking at all likely at the time of writing, then I fear that Disney will plough on regardless. That being said, the reviews of TROS are mostly negative from what I’ve seen, and many of the issues we’ve raised with the film here have been articulated by others. Perhaps we’d never be pleased in any case. Perhaps we’re expecting too much.

Brooker

Ironically, my hopes and expectations for Star Wars are guided by what I wanted to see, or what I think I wanted to see, back in 1983 when I was a boy -- and they make me sound, some 36 years since Return of the Jedi, like a grumpy old man. But I am happy that there are currently two mainstream, official Star Wars narratives, running at the same time across distinct media platforms, that seem to appeal to different generations and fan groups. If some viewers are thrilled and inspired by The Rise of Skywalker, I think that’s genuinely great. I wouldn’t argue with their interpretation. I’m also very glad that The Mandalorian is providing the kind of Star Wars I enjoy. Perhaps the films can’t please everyone any more, but the fictional galaxy is easily large enough and diverse enough for us to have our own distinct stories. Though I was clearly disappointed by the conclusion to the Skywalker saga, thanks to The Mandalorian I now feel more ‘seen’, more recognised by and engaged with the Star Wars franchise than I have in years.

Will Brooker is Professor of Film and Cultural Studies and Head of the Film and Television Department at Kingston University, London. Professor Brooker’s work primarily studies popular cinema within its cultural context, situating it historically and in relation to surrounding forms such as literature, comic books, video games, television and journalism. In addition to the numerous essays and articles on film and fan culture that he has published, his books include Why Bowie Matters (2019), Forever Stardust: David Bowie across the Universe (2017), Star Wars (2009), Alice’s adventures: Lewis Carroll in popular culture (2004), Using the Force: Creativity, Community and Star Wars Fans (2002), and the edited anthologies The Blade Runner Experience (2004) and The Audience Studies Reader (2003). He is also a leading academic expert on Batman and the author/editor of several books on the topic, including Batman Unmasked (2000) Hunting the Dark Knight (2012), Many More Lives of the Batman (2015).

William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Film and Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He is co-editor on the books, Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth (with Matthew Freeman, for Routledge 2018), and Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion and Reception (with Richard McCulloch, for University of Iowa Press, 2019). William is a leading expert on reboots, and is currently writing a monograph on the topic for Palgrave titled Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia. He has published on a wide-range of topics, including Star Wars, Batman, James Bond, Stephen King, and more.