Cult Conversations: Interview with Ekky Imanjaya (Part II)

/What films stand out as exemplars of the sub-genres you mention, such as Kumpeni and Perjuangan? Can you explain more about these sub-genres in the Indonesian context? Do they draw upon Western traditions (such as the Italian Cannibal boom of the 1970s, for instance? Are there any sub-genres you think are exclusively generated by Indonesian filmmaking?

Actually, I already wrote about the subgenres in my papers in 2009 and 2014. Here, I will elaborate again.

I find Karl Heider’s theories useful to do genre mapping of popular genres, considering that only few scholars wrote seriously and deeply about popular films, let alone exploitation and B-grade movies. Heider suggests various genres and types into which most Indonesian films can fit comfortably (Heider 1991, 39-40). Heider argues that popular genre films are the best examples to do a cultural analysis on since films directed by auteurs or for the purpose of artistic expressions were intentionally detached from their cultural origins.

I argue, based on Heider’s theory, that there are two basic types of classic Indonesian exploitation films. The first one are films that have stories rooted in Indonesian tradition, history, folklores, or storytelling. Commonly, these kinds of films are full of strangeness, exoticism, and otherness, according to the perspectives of Western fans. The Legend genre, Kumpeni genre, and Horror genre belong to the first basic type of the films, all of which contain elements of mysticism and/or traditional folklores.

Suzzana in White Crocodile Queen (1988)

The Legend Genre includes dramatizations of traditional legends or folktales. The main protagonists usually have supernatural powers. This genre includes costume dramas, historical legends, or legendary history. For Example: Snake Queen and White Crocodile Queen.

Suzzanna as snake queen

The Kumpeni genre are films which tell stories of the conflict between the Dutch and the Indonesians (17th-19th centuries). The term Kumpeni is the local term of compagnie which comes from Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), or the Dutch East India Company (1602-1799). The prototypical plot pits the eponymous hero with supernatural and mystical powers (Jaka Gledek, Jaka Sembung, Pak Sakerah) against the Dutch forces. Jaka Sembung or ‘The Warrior’ series is the best example of this sub-genre.

Horror in the “Crazy Indonesia” context” deals with supernatural powers and supernatural monsters, and have a direct connection with traditional folklores. For example: Queen of Black Magic, Mystics in Bali, and Satan’s Slave.

The second type are the ones that have many similarities with international exploitation films. I argue that there are three genres formulated by Heider with these kinds of characteristics:

Firstly, the Japanese Period Genre. Set in Japanese colonial era (1942-1945), usually about Indonesian women who are kidnapped and harassed by the Japanese army, and later, became a prisoner or saved by a Japanese officer. This genre is very close to ‘womensploitation’ and Women in Prison films. War Victims is a good example of this genre.

Secondly, Perjuangan (struggle) period films, which are about the battles to defend a nation’s independence (Heider 1991, 42-43); these look similar to mainstream American action B-grade films. Both genres are rooted in historical stories of wars in Indonesia. Examples of these films include Daredevil Commandos, Blazing Battle, and Hell Raiders.

And lastly, cannibalism or, as Heider’s puts it, ‘expedition films’. Some scholars and critics call these “Jungle films” (Tombs and Starke 2008, Sen: 1999, Tombs 1997). The plot consists of a group of “civilized” people discovering unknown places and encountering its native inhabitants (Heider 1991, 45), as in Primitif and Jungle Virgin Force. In an interview with Mondo Macabro filmmakers, Gope Samtani the producer clearly mentioned the 1970s Italian Cannibalism as the inspiration to make Primitif.

JUNGLE virgin force (1983)

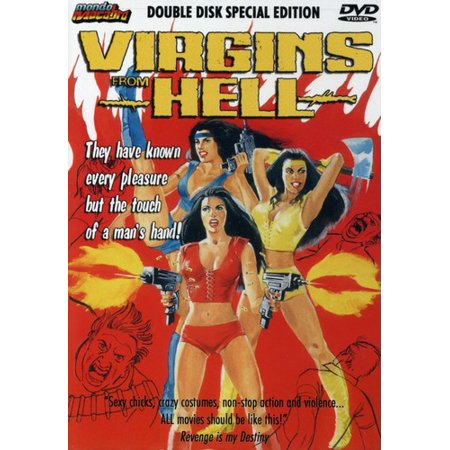

There are also films that simply imitated WIP formula, such as Escape from Hell Hole, and Virgins from Hell.

Of course, there are some hybrid films with the characteristics of more than one genre, and can be categorized and fit in some sub-genres of Western exploitation categories. For example, I argue that characteristics of the Mockbuster or Remakesploitation (in Iain Smith’s term) are embedded in Lady Terminator, which is a blend of Legend and Horror, and has “adopted” parts from Terminator mixed with the traditional folklore of The Queen of South Sea; whereas Intruder is a Rambo rip-off.

As with much of Western exploitation, then, the Indonesian tradition seems to borrow and plunder already existing and successful properties from North America, Lady Terminator and Intruder’s Rambu being two of your examples. Would this be a fair assessment? Are there other examples of Indonesian exploitation cinema “remaking” or “adapting” elements of US mainstream filmmaking?

I must go back to the early 1980s when the government founded Prokjatap Prosar (Kelompok Kerja Tetap Promosi dan Pemasaran Film Indonesia di Luar Negeri/ The Permanent Working Committee for the Promotion and Marketing of Indonesia Films Abroad) and brought Rapi Films’ Gope Samtani and Parkit Films’ Raam Punjabi to international film markets in prestigious film festivals such as Cannes, Berlinale, and Milan’s MIFED (Mercato Internationale Del Film Del TV & Del Documentario) (1982-1983). The producers learned how to deal with global film markets, to understand the global demands and tastes, and how to sell their own films to potential buyers. And starting in 1985, after Prokjatap Prosar got dismissed in 1983, they went independently to international film markets, including Milan, Cannes, Berlinale, and Los Angeles.

And, after learning the nature of transnational film markets, they intentionally started to make films that could fit in global market’s taste and demand, and one of the strategies is by doing joint-production as well as using Caucasian actors. Although in 1984 Rapi Film collaborated with Rapid Film GMBH (Munich, Germany) to make No Time to Die (Danger - Keine Zeit zum Sterben / Menentang Maut), the joint-production trend started in 1987 as Rapi Films and Troma Entertainment co-produced Peluru dan Wanita, globally known as Jakarta (Triangle Invasion) directed by Charles Kauffman). The co-production projects between two film companies produced three more films, including the infamous wrestling and redubbing film Ferocious Female Freedom Fighters.

Other film companies followed the co-production mode. Some such films included Bidadari Berambut Emas (Lady Dragon 2, Ackyl Anwari, 1992), Harga Sebuah Kejujuran (globally known as Java Burn/Diamond Run, Deddy Arman & Robert Chapell, 1988), and Jaringan Terlarang (Forceful Impact, Ackyl Anwari 1988), and Dangerous Seductress (Bercinta dengan Maut, Tjut Djalil, 1992). In these films, they tried to duplicate the look and the feel of Western exploitation films.

Not only imitating the style of American exploitation films, they also include foreign actors, both professional (Billy Draco, Mike Abbott, Chyntia Rothrock, among others) and amateur ones (Barbara Constable and Ilona Agathe Bastian were tourists, Peter O’Brian was an English teacher), and directors (such as Guy Norris) in these films. Actually, a year before Jakarta, there was a movie titled Dendam Membara (Final Score, Arizal 1986) starring Chris Mitchum.

So, we can see Indonesian films with Rothrock starring in them in Angel of Fury/Triple Cross (1990) and Tiada Titik Balik (Lady Dragon, 1992).

Beside that, as mentioned earlier, I argue that there are Americanized exploitation subgenres in “Crazy Indonesia” films, similar with the formula and characteristics of womensploitation, mockbusters, cannibalism, and women-in-prison films. I claim that, based on the formula and characteristics, Japanese period films are Indonesian version of women-in-prison films, and War Victims is one of the films. WIP films in Indonesian contexts include Virgins from Hell and Hell Hole.

Lastly, I must mention the success story of Primitif, Barry Prima’s first movie. In an interview filmed by Pete Tombs and Andrew Starke (titled Fantasy Films from Indonesia), the producer openly admitted that they made Primitif in order to make local “Jungle Film”, just like the trend of Italian’s Cannibalism. This is the first film being sold in international film market--sold in the 1979 Cannes Film Festival through an Italian distributor, SBO. Interestingly, the distributor seemed to hide the fact that Primitif was an Indonesian film. Primitif was also screened in a West German TV station in 1979 and 1980.

And finally, which five films would you choose that represent the ‘best’ that Indonesian exploitation cinema offers and why?

Lady Terminator (Tjut Jalil, 1988).

I think the film is one of the most popular and most discussed films online related to Indonesian movies. It is on the list of 100 Cult Cinema (Mathijs & Mendik, 2011) which includes films such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and El Topo (1970). The film is a perfect example how the filmmakers tried to blend Hollywood’s action film (namely Terminator) and legend genre with famous local folklore and mysticism. In its promotional material, it says :” “Even the jaded patrons of 42nd street were shocked to see how the lustful Lady T dispatched her victims...!".

In Indonesian context, the film caused “moral panic” and was banned after 11 days of public screenings in 1989 because the film was considered as being “too nasty”. The film got post-production overseas and without passing any official censorship, and returned to Indonesia illegally in home video format.

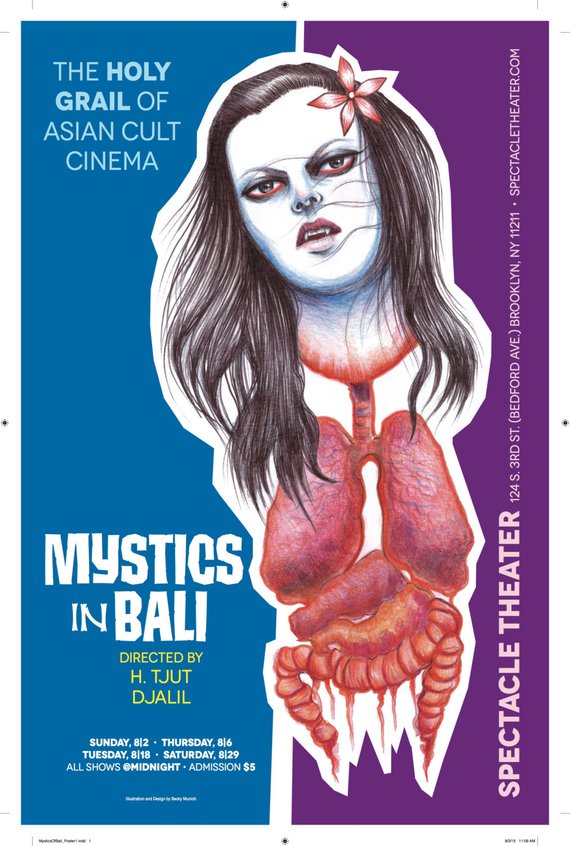

Mystics in Bali (Tjut Djalil, 1981)

In his book, Mondomacabro: Weird and Wonderful Cinema around the World, Pete Tombs named the chapter of Indonesian films by “Mystics in Bali”. Later, Mondo Macabro DVD labels the film as “The Holy Grail of Asian Cult Cinema”.

The film is infamous among global online fans for its exoticism and weirdness of “Far East mysticism”, such as “the flying head eating unborn child” and “the lady who turned into a pig”. the promotional material says: “This is the film that introduced a new kind of monster to the world’s cinema screens. A sensation on its initial release in Asia, Mystics in Bali was deemed too bizarre and shocking to be screened in the West.” One of my colleagues, Jan Budweg, informed me that he found a document in Germany stating that the film was banned in the country for being “too weird”.

The film tells a story about how to become a Leak, “the most powerful black magic in the world”. And, interestingly, when most of local horror films are strongly related to Islamic teachings and Muslim clerics became the “savior”, Leak is a Baliness ghost with the rich culture of Bali’s Hinduism.

Jaka Sembung (The Warrior) (Sisworo Gautama Putra, 1981)

Let me start with my own experience in 2008. After I finished presenting my final paper at Universiteit van Amsterdam, some of the young students approached me and expressed their gratitude for watching the action of Rawarontek or Pancasona charm. “Thank you for introducing me with this Asian superhero. Here, there is no such thing like it, especially when the separated body and head can unite after being chopped off.”.

Jaka Sembung is my favorite local hero. I consider him as local Superhero since he has supernatural* powers and fight against colonialism and protect his people.

And one of the “magic” of the film, as well as other films, is the Special Effect, thanks to El Badrun.

Special Silencers (Arizal, 1979)

Also one of the most discussed “Crazy Indonesia” films in the internet. In AVManiacs, November 2011, the fans consider the film as “.. one of the craziest, goriest, wildest, over-the-top Indo-fantasy-flicks ever” and “…gore, violence, trees growing out of peoples bodies in very gory detail, bad kung-fu, bad romance, Corny dialogue, weirdness, weird magic, fire, torture by smelly shoes, rats, snakes, more gore, Barry Prima, Eva Arnaz…”. Moreover, the film is “…even crazier than the Turkish stuff I've seen.”. No need further explanation, I guess.

Ferocious Female Freedom Fighters (Jopi Burnama, 1982)

This is the first Indonesian films being circulated globally in DVD format as well as the first (and the only?) film being redubbed intentionally (in VHS release: 1997).

DVD release: Oct 14, 2003) for marketing purpose by an international distributor. Lloyd Kaufman’s Troma Team decided to rework the original film by rewriting and rerecording the dialog and music score in order to make it into a “Troma film”. They call this reworking process “Tromatized”. As a result, influenced by Woody Allen’s What’s Up Tiger Lily (1966), the film has totally different story and flavour.

In his 1998 book (co-written with James Gunn), Lloyd wrote “We change a kickboxing Rambo type of hero into an Elvis impersonator. We change the lady in the film from a serious Indonesia heroine into a Jewish-mama-type of person…”. They also add new sound tracks including, as Kaufman puts it in his book, “…numerous instances of farting, bad sportsmanship, and a chronically masturbating little boy who was singularly obsessed with his ejaculate and the size of his mother’s breasts”.

In 2001, Joko Anwar wrote a phenomenon of the discussion of Indonesian B-grade movies in some midnight movies forums, in the Jakarta Post. And he mentions the film: “Troma pushes it to the lowest point of stupidity by redubbing it with very dumb dialog that plays for pure laughs”.

Satan’s Slave (Sisworo Gautama Putra, 1980)

Considered as one of the scariest film by 1980s generation in Indonesia, this film is the first local Zombie film enriched with local tradition and context. The film has no specific motive that commonly exists in domestic horror films, such as “ oppressed female character, mostly being raped, became a ghost and seek revenge”. The powerful female shaman just picked random people who “are far from religious path” to become satan’s slave. So, it could be anyone, it could be us.

The film is the reason Joko Anwar remade Pengabdi Setan (2016) and brought it to the next level and made this B-grade film into an artistic world class horror films and became the first position in 2016 box office films and gaining more than 4 million spectators—the first Indonesian horror film in that position.

Ekky Imanjaya is a faculty member of Film Program, Bina Nusantara University (Jakarta). He just finished his PhD study in Film Studies at University of East Anglia. The title of his thesis is “The cultural traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema”. His scholarly papers were published in some journals, including Cinemaya, Asian Cinema, Plaridel, Jump Cut, and Cinematheque Quarterly. His popular articles were published in some media, including Rolling Stone Indonesia, Catalogue of Taipei International Film Festival, and Südostasien. In 2015, Ekky guest edited a special issue titled "The Bad, The Worse, and The Worst: The Significance of Indonesian Cult, Exploitation, and B Movies" in Plaridel: A Philippine Journal of Communication, Media, and Society.

![final score].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/592880808419c27d193683ef/1547205941837-UU8H53CM4AJ0REP972PI/final+score%5D.jpg)