Cult Conversations: Interview with Ekky Imanjaya (Part I)

/Happy New Year aca-fans and all the best for 2019! Our first installment of the Cult Conversations series of the new year features Ekky Imanjaya, who recently completed—and successfully defended—his PhD thesis on Indonesian exploitation cinema at University of East Anglia (supervised by Mark Jancovich and Rayna Denison). This is a topic that I literally had zero knowledge about, and learned a great deal from Ikky during our conversation, which encouraged me to go off on one of my online hunts for these films (the hunt is part of the fun, right?). I mean, who wouldn’t immediately want to watch films with titles such as White Crocodile Queen, Ferocious Female Freedom Fighters or Lady Terminator? I am sure that cult scholars and fans—and scholar-fans— will find some hidden gems in the following interview and the geographical and historical context of Indonesian exploitation/cult cinema is fascinating, to say the least. I very much look forward to following Ekky’s research in the future.

Lady Terminator! “She mates…then she terminates!

— William Proctor

When did your personal journey into Indonesian exploitation cinema begin? Would you say you were a fan first? Or was it your academic pursuits that led the way?

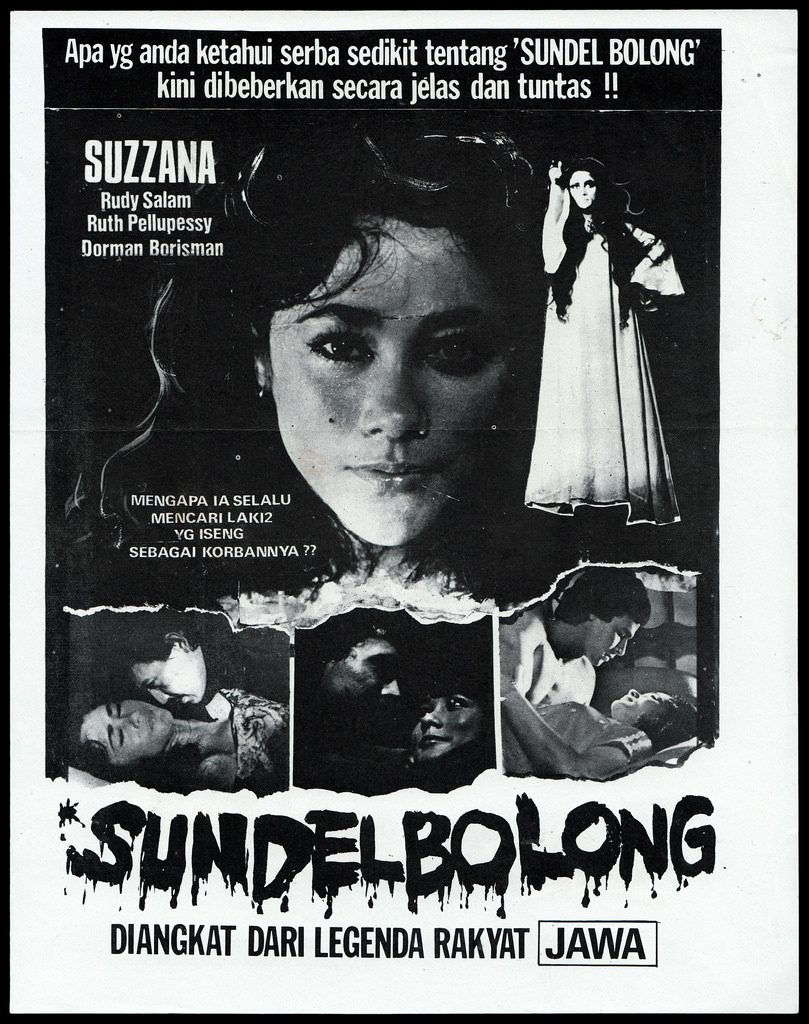

Well, like many of my friends, when I was a kid back in the 1980s I loved watching local exploitation films. Of course, at that time, we were not familiar with the term as we only wanted to watch the action/martial art scenes and legend-fantastic stories. Kids like me watched the movies based on our favourite movie stars (and genres such as mystics or martial arts), instead of directors. So, we loved watching Barry Prima’s films, or Suzzanna’s films (known as ‘the horror queen of Indonesian Cinema’). They are most probably the most favorite of the 1980s cult icons—despite that Indonesian people never label the films or the stars as “cult” and I could not find any scholars or critics using the term “cult cinema” in analysing Indonesian films, until the films got recirculated in the early 2000s. Such films, borrowing terms from Barry Grant and Mathijs and Sexton respectively, back in the 1980s and 1990s were considered as “Mass Cult” and “Cult Blockbusters”.

Barry Prima: Indonesian Actor and Martial Artist

Although I watched these kinds of classic Indonesian trashy films and became a fan when I was a kid, my scholarly interest in these kind of films began in 2007 while I was doing my master study at Universiteit van Amsterdam. Before 2007, when I was a film journalist, those films were (and still are) overlooked and shunned by most film critics, film journalists, and film scholars, except when discussing controversial topics or particular fields of study such as gender studies or analysis of social classes. After 1998, when New Order’s President Suharto stepped down, people were excited to witness and enjoy the works of the New Generation of filmmakers with their innovation and creativity in less state-controlled situations. However, nobody focused on these trashy films.

Suzzanna Martha Frederika van Osch (1942—2008)—’the queen of Indonesian horror cinema.’

However, in 2007 I found a DVD titled “Mystics in Bali” distributed by Mondomacabro DVD in Boudisque, Amsterdam. Later that week, I found out that there are many of Indonesian exploitation from the New Order era (particularly 1979 To 1995) that were globally recirculated in the 2000s by transnational distributors and celebrated by global fans. The global fans even have the term “Crazy Indonesia”, and seen as a thread in the AVManiacs forum on September 14, 2007.

Initial questions occurred to me: why are Indonesian films of the 1980s and 1990s being internationally circulated and celebrated abroad 35 years after their original release? Why is there interest in exploitation films and not the official “Indonesian Films” as a representation of official and legitimate culture? Why were there many trashy films produced and circulated nationally and transnationally in the New Order period, the years commonly known for strict censorship and state-control within film industry?

In domestic mass media, it was prominent director and screenwriter Joko Anwar, then film reviewer for The Jakarta Post, who wrote an article titled ‘Badri films a big hit overseas,’ published on 9 December 2001. Joko states that the films (he specifically mentioned Ferocious Female Freedom Fighters (FFFF), Lady Terminator, and The Warrior/Jaka Sembung series) are “…still being talked about and looked for on videos by many bad-movie lovers worldwide and are widely discussed in some midnight movies forums”. He even recommended some exploitation and cult film websites for more details and for online shopping. Joko admitted that those B-movies from, and outside of, Indonesia are one of the reasons why he makes films. He repeatedly praised the films by comparing classical films with recent ones. In 2005, Anwar uploaded the DVD covers of the transnational version of the movies on his ‘Multiply’ blog, which caused many Indonesian fans to want to know more about the exported film and purchase them where possible. Joko Anwar’s activism is significant in engaging many post-New Order local fans with the “Crazy Indonesia” phenomenon, and also can be considered as the bridge for local film enthusiasts to recognize and, later, celebrate the films.

Inspired by Joko Anwar’s Multiply account and my own discovery, I started to undertake research on the topic, and presented a topic as my final assignment for a module titled “Fictional Events and Actual Emotions”, convened by Dr. Tarja Laine in 2008. After presenting the idea at the B for Bad Movies conference in Monash University (Melbourne) in 2009, I finally published the paper called ‘The Other Side of Indonesia: New Order’s Indonesian Exploitation Cinema as Cult Films’ in Colloquy. And, finally, I was invited to be the guest editor of Plaridel: A Philippine Journal of Communication, Media, and Society Special Issue, Vol 11, Issue No. 2, 2014. The topic of my special issue is “The Bad, The Worse, and The Worst: The Significance of Indonesian Cult, Exploitation, and B Movies".

In 2009, I emailed Professor Mark Jancovich proposing this idea and asking him to become my supervisor for my PhD study. In less than 5 minutes, he said yes. But it took me 4 years to study at UEA (I started in January 2013), since it was difficult to get the funding, particularly with this “unusual” topic.

Your PhD thesis, The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema, is certainly a valuable area of study and one that has not been studied in great depth in Western academia. How would you explain your thesis to someone who is not familiar with cult cinema in the Indonesian context? How does Indonesian exploitation cinema differ from the grindhouse tradition in the US-context in terms of content and theatrical exhibition?

My PhD study focused on two key terms: the Politics of Taste and Global Flow related to the film traffic of the films being analysed, namely, transnational Indonesian films from 1979-1995 recirculated globally in early 2000s and 2010s. My PhD thesis critically argues against mainstream point-of-views, which commonly devalue Indonesian trashy films. Firstly, I challenged the “official history” of Indonesian cinema through the framework of cultural traffic, by including and highlighting the significance of exploitation and B-films, and how the films need to be part of any serious discussion about Indonesian cinema. Secondly, I argue that, from the viewpoint of the global flows of the films, classic Indonesian exploitation films are both the effect and the cause of a conflict of interests of various politics of taste applied by several agencies: the State, cultural elites, local film producers, local film distributors and exhibitors, local audiences, transnational distributors, and global fans.

Regarding, the different between Indonesian cult movies and other cult movies, actually, there are two perspectives: the perspective of Western/global fans and transnational distributors, and local audience and producers/distributors.

From the global perspectives, they consider what I called “classic Indonesian exploitation films” as cult movies. The films were originally produced, distributed, exhibited in Indonesia, as well as exported (or sold in international film markets), produced by Indonesian filmmakers (and joint-production with filmmakers from other countries), particularly between 1979 and 1995. The films were reworked and recirculated by transnational distributors, legally and illegally, in the early 2000s and labelled as “cult movies”. The most popular distributors include Mondo Macabro (I wrote a paper about them, and will be published soon in Plaridel journal), Troma Entertainment, and VideoAsia’s Tale of Voodoo.

Global fans have the term: “Crazy Indonesia“--a term popularized by Jack J when he started a thread with the same title in the AVManiacs forum, 2007. In the first posting of the thread at AVManiacs (14/09/2007), Jack states that he borrowed the title for this thread from another member, Gaenter Muller, who used it for his website, ‘Weird Asia'. Unfortunately, I can’t find a way to trace the website.

The fans wrote reviews or discussed the films in the thread, as well as in their own blogs, such as Cinema Strikes Back, Mondo Digital, 10K Bullets, Ninja Dixon, Critical Condition, Damn That Ojeda!, and Backyard-Asia. Regarding Indonesian films, they focus only on “Crazy Indonesia” films and, at the same time, reject other kinds of Indonesian films.

Borrowing from Karl Heider, I argue that they love particular sub-genres of Indonesian films, namely “Indonesian genres” (Kumpeni, legend, supernatural-horror/mystics) and Americanized exploitation subgenres (Japanese Period genre which is similar with womensploitation, Perjuangan/Struggle period genre or action/war movies, mockbusters, cannibalism or Jungle/Expedition films, and Women-in-Prison). Hence, they are only interested in some specific genres and styles from a specific era of production.

The local perspectives are different. When I undertook my PhD research, I could not find either scholarly or popular articles using the term “exploitation” or “cult” related to Indonesian movies, until those 1980s and 1990s movies were redistributed globally in early 2000s. Some critics did mention similar terms, such as “trashy movie”, “slapdash movies”, and “poor quality movies” by Salim Said, Heider’s description of “The art of movie advertising” which is quite similar with the tradition of exploitation films in the Western tradition. Rosihan Anwar once also used the term “sexploitation” in 1978. This is not surprising considering that the movies are considered unimportant and against the official definition of “Film Indonesia”, which should represent the “faces” of Indonesia, true culture, and with cultural and educational purposes (or, “Film Kultural Edukatif”).

Hence, in some cases, I had difficulties applying the Western-centric concept and definition of “cult movies” onto the context of Indonesian cinema, particularly those produced in New Order era. I am currently developing an idea for an academic paper regarding “Cult Movies, Indonesian Style”. If we agree that the essence of “cult movies” is concerning lively celebration and the rituals of their militant followers, most local audiences in the past and in the 2010s have different styles. There were no fan rituals, cosplay, comic-con, fanzines and so forth, until a few years ago. The traditions associated with Western cult cinema, such as Midnight Screenings, Midnight Movies, Drive-in cinemas and Double Bills are not common in Indonesia, but they have “Layar Tancap” (traveling cinema shows) tradition in rural and suburb area (my paper on this matter will be published soon in Cine-Excess Journal). And most of the films were produced by major film companies and were released theatrically and on home video format (traveling salesmen usually came door-to-door in the neighborhood offering the Betamax video format) for mainstream audiences, and became popular films with some of them even gaining blockbuster status.

Regarding film references, most of local audiences are not familiar with, for instance, Rocky Horror Picture Show or El-Topo, but they love the Dangdut musicals starring Rhoma Irama, or comedies starring Warkop DKI, or Benyamin Sueb, or propaganda films such as Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI (The Treason of G30S/PKI, an official version of the 1965 event)—which were not circulated in global VHS circuits in the 1980s and are not in the cult DVD circulation of the 2000s.

The terms ‘trashy’, ‘slapdash’ and ‘poor quality movies’ to describe Indonesian exploitation cinema seems to be aligned with discourses in the Western context. How do you feel about these films being labelled in such way as to mark them out as ‘bad’ films? Do fans ‘love to hate’ these films? Or are they described as ‘so bad that they are good’? Given that fans, as you say, reject certain films and include others, is Indonesian exploitation cinema a form of what Jeffrey Sconce terms ‘paracinema’? There certainly appears to be similarities with the cultural distinctions and binaries constructed around exploitation and cult in the Western content. Even the term ‘trashy’ constructs cultural distinctions between exploitation and mainstream, as in the Western context.

This questions can be answered from two perspectives: the Indonesian perspective in New Order era, and the more recent global fans. Let me begin with the first one.

As I mentioned before, there is no term for “cult movies” or “exploitation movies” (as discussed in Western countries). The terms ‘trashy’, ‘slapdash’ and ‘poor quality movies’ came from a few important figures of the cultural elite back in 1980s and 1990s. At that time, domestic exploitation films were mushroomed and became mainstream and some of them became box office films. Although New Order government applied sharp censorship and strict regulations towards the film industry, they still had interests in this kind of films. Naturally, they have terms such as “National Cinema” that can represents “the true Indonesian culture” or in attempt to “seek Indonesian faces on screen”, and should be Film Kultural Edukatif (films with cultural and educational purposes), known as the “qualitative approach”, but still they had the “quantity/audience approach”. For example, the Minister of Information Mashuri Saleh issued the Ministerial Decree no. 47/1976, which states that film exporters are obligated to produce five films (later, reduced to three) for the right to import films (Said 1991, 88). This quickie quota policy was in response to the decline of film production in 1977 (from 77 in the year before to 41, as written by Said in 1991). As a result, the quantity of films increased significantly. For example, the 1978 Indonesian Film Festival received the largest number of entries in the New Order era. On the other hand, many of these films are criticized for not been good quality. Salim Said underlines that the films are “not just slapdash films but films with an overemphasis on elements such as sex and violence”, and this phenomenon led to “the rise of trashy movies” (Said 1991, 89-90). That was where the terms came from.

The main idea of quantitative/audience policy was to “let the quantity of films grow first, therefore the quality will automatically follow” (as written by senior film critic JB Kristanto in 2004). Interestingly, in Indonesian context, the exploitation films were the mainstream films, whist most of Film Kultural Edukatif had difficulties in getting audiences.

The other perspective is the perspective of global fans and transnational distributors. They like the strangeness, the weirdness, the otherness of the films. As I mentioned above, they have their own term, “Crazy Indonesia”, which is in line with some of Karl Heider’s definition of Indonesia’s sub-genres, such as Kumpeni (local heroes fights Dutch colonial army with supernatural powers), Legend (folklores/fantasy with supernatural and magic powers), Japanese Period (W-I-P), and Jungle/Expedition (Indonesian style of cannibalism) genres. The difference between the “Crazy Indonesia” films and the exploitation films from Western countries relies on the exoticism of these subgenres. In an interview with myself, Pete Tombs, the co-founder of Mondo Macabro, shares the same argument:

“Again, to us in the West, the mythology they explored (South Sea Queen, Sundel Bolong etc.) was new and very “exotic”. There was also something interesting in seeing western exploitation staples, such as the women in prison movie or the monster movie, being filtered through Indonesian eyes. Finally, I suppose for us there was a feeling that things like supernatural horror and black magic were maybe taken a bit more seriously by audiences in Indonesia than they were in the West, for cultural/historical reasons, so the films weren’t so self-conscious or “camp” as UK or US productions” (Imanjaya 2009d, 148)

Can you explain more about the political climate in which these films emerged and re-emerged? Terms such as “New Order” may need explaining for readers unfamiliar with exploitation in the Indonesian context.

The New Order regime era was established in 1966 and ended in 1998. The years 1965-1966 were a big transition point for Indonesia. In the previous decade, there were ideological battles and political polarizations among many parties. The Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia, or PKI), one of the biggest political power in Old Era, was destroyed and Suharto became the President. New Order accused PKI to take over President Sukarno (the previous president) in September 30, 1965, thus the Army under Suharto “destroyed” and banned PKI’ and the members (or people who were accused as members of PKI) were imprisoned or killed. On the other hand, if you watched Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, you can find the “other perspective” of the event.

Learning from the final years of the “Old Order”, an era that was marked by economic and political instability, Suharto’s “New Order” framed all aspects of potential Communist infiltration of cultural output as subversive and put the film and media industries under military control, and thus established a level of oppression and censorship. However, at the same time, Suharto tried to build the nation, including the film industry. On one hand, they tried to dominate every aspect of life under the guise of security, development, and stability . For example, in the film industry, the government applied strict censorship and controlled all aspects of film production from screenwriting to distribution and exhibition. On the other hand, The New Order had several policies designated to rehabilitate the development of the film industry and support the import of foreign films. Ministerial decrees were enacted to improve film development with a focus upon a “quantity approach” or “audience approach”. This kind of decrees paved the way of exploitation films to bloom.

Ekky Imanjaya is a faculty member of Film Program, Bina Nusantara University (Jakarta). He just finished his PhD study in Film Studies at University of East Anglia. The title of his thesis is “The Cultural Traffic of Classic Indonesian Exploitation Cinema”. His scholarly papers are published in some journals, including Cinemaya, Asian Cinema, Plaridel, Jump Cut, and Cinematheque Quarterly. His popular articles were published in some media, including Rolling Stone Indonesia, Catalogue of Taipei International Film Festival, and Südostasien. In 2015, Ekky guest edited a special issue titled "The Bad, The Worse, and The Worst: The Significance of Indonesian Cult, Exploitation, and B Movies" in Plaridel: A Philippine Journal of Communication, Media, and Society.