In Search of Indian Comics (Part Four): In Orjit Sen's Studio

/This is the fourth and final installment of a series of posts dealing with the current state of comics and graphic novels in India. It is based on my experiences in Dehli last summer, hosted by Parmesh Shahani from the Godrej India Culture Lab. Cynthia and I parted company with Vartikka and head out to the outer suburbs, where we are going to visit Orijit Sen in his studio. I introduced Sen in passing a few posts back, but let me take a moment to give this man the props he is due. Sen's The River of Stories is often cited as amongst the first important graphic novels to come out of India. It is currently out of print but will be coming back soon, so I am personally looking forward to engaging with it more fully in the near future.

Sen offered an account of its creation in the special issue of Marg on "comics in India." This is some of what he had to say:

"The universe is not made of atoms, it's made of stories. Landscapes tell tales, geographies contain histories, trees express emotions, houses are characters, and rocks can be moody...When in 1991 I started work on River of Stories, my first graphic novel project, I travelled to the Narmada River Valley where my story was to be set. I had no clear notion of what I was going to do there but I knew I wanted to experience the land, meet the people who belonged to it, sit on the banks of the ancient and storied river, and watch it flow....Over several visits, I stayed variously at rest-houses, with Andolan activists in their offices in small market towns, with Adivasi families in their village homes, and sometimes in remote ashrams and schools managed by Gandhian organizations. I attended Baghoria festival fairs, wedding feasts, religious ceremonies and political rallies, journeying on trains, buses, jeeps, bullock carts, bicycles, and on foot. Everywhere I sketched, made notes, took photographs and listened to people's stories. Gradually, the people, the river, the hills, forests, streams, roads, bridges, plantations, hamlets, houses, tools and objects became internalized as part of the visual vocabulary with which I sought to fashion the story of the Narmada Valley and the struggle of its people. I laboured to not just capture slives of life, but to absorb entire chunks of lived experience in the Narmada Valley. I felt this was the only way one could tell the truth about a place and its people."

What emerged was ethnographic in its focus on a people and activist in its attention to their struggle for social justice.

Sen runs the People Tree shops from the front part of the studio, so it is piled high with fabric and clothing in various states of preparation, and there are people sewing away.

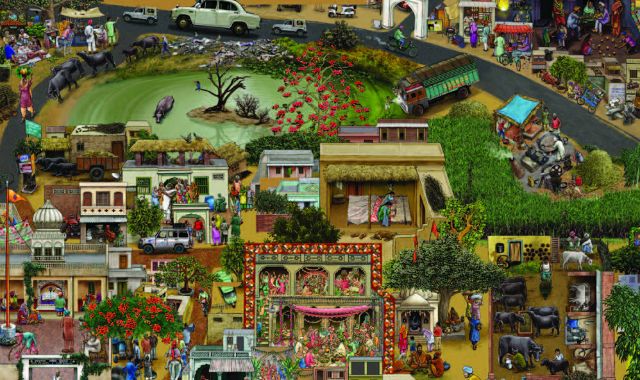

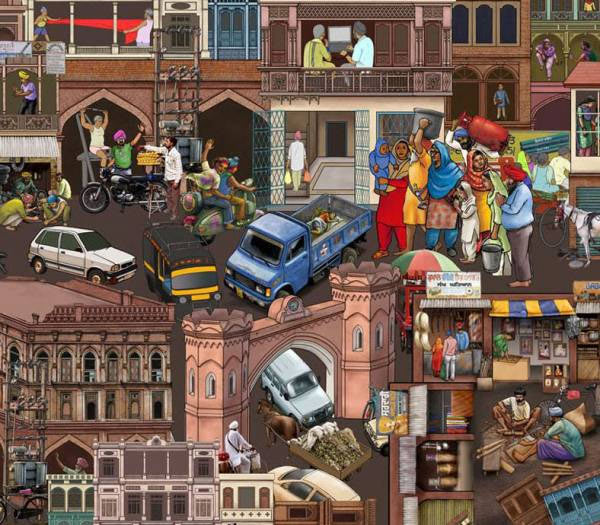

In the back of the shop, he has a team of young artists working on a very interesting project. They are designing a set of murals depicting the history and everyday life practices of the city of Hyderabad on commission for a local art gallery owner. The work is intricately detailed, combining aspects of the miniature painting, street murals, and especially comics. And there are surprising and compelling shifts in perspective which force you to continually reposition yourself in relation to the work.

I was fascinated by what he was producing, since it includes so many details of street life we had observed during our time here, but also manages to move back and forth through time, showing the layers of that city’s history and culture. These images are being developed digitally and will be printed out in huge sheets for the gallery space, but the hope is to use those images to pitch the city to hire his team to paint them onto actual walls and incorporate it into the geography of the city itself. Below are a few images I've found online depicting an earlier and similar mural project Sen oversaw, and they give you a sense of the scale and representational strategies involved with this project.

His team includes a Japanese manga artist who is otherwise trying to produce manga with Indian content, a woman who is a children’s book illustrator, and two guys, both of whom are part of the emerging generation of young comic book artists here. One of them mentioned having run the local 24 hours Comics event (this is a practice created by Scott McCloud where lots of artists pledge to produce a comic book in 24 hours). They are spending weeks at a time wandering the streets of Hyderabad taking photographs and drawing sketches – mostly sketches since Sen believes the simplification involved in drawing leaves more useful impressions for comics work.

His team includes a Japanese manga artist who is otherwise trying to produce manga with Indian content, a woman who is a children’s book illustrator, and two guys, both of whom are part of the emerging generation of young comic book artists here. One of them mentioned having run the local 24 hours Comics event (this is a practice created by Scott McCloud where lots of artists pledge to produce a comic book in 24 hours). They are spending weeks at a time wandering the streets of Hyderabad taking photographs and drawing sketches – mostly sketches since Sen believes the simplification involved in drawing leaves more useful impressions for comics work.

We have a great conversation with Sen and Vishwajyoti Ghosh, both tracing the emergence of a graphic novel scene in India. Sen described how he had read and loved comics, but could get no interest in them as an art student, until Art Spigelman published Maus and this suddenly sparked an intense dialogue about graphic storytelling, out of which emerged, a decade later, River of Stories.

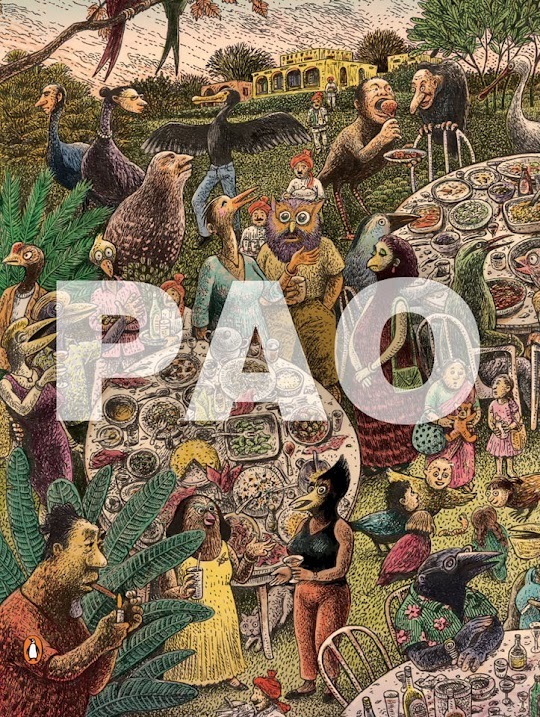

Ghosh was part of the next generation who was inspired by Sen’s work and together, they have edited several important anthologies of comics by contemporary Indian comics producers -- most notably, PAO.

They seem to go around recruiting young talent and trying to connect them with publishers. Sen explains in the book's introduction:

"The Pao Collective is a self-funded and self-propelled group of very disparate individuals who have managed to work together over a very long time and put in a hell of a lot of collective effort to conceive, drink beer, create, drink beer, mentor, share smokes, edit, eat mutton rolls, agree to disagree, drink beer and put together this anthology involving some twenty artists and authors."

Pao's contributors represent the core of the contemporary graphic storytelling movement in India, and the entries represent a range of visual styles, from the highly cartoonish or dream-like, to the photorealistic, from photo-collage to more text-centered works, and from modernism to very traditional folk techniques, all of which convey the possibilities of what sequential art might become in this country.

This piece, contributed by Raj Comics, borrows from the Japanese manga tradition and captures something of the dynamic movement of people and vehicles across India's densely packed urban areas.

The above image comes from Sarnath Banerjee, whose work, Corridor, we discussed last time: it suggests his keen observation of the details of everyday life.

"The Pink," written by Salil Chaturvedi and illustrated by Priya Kuriyan, is a surrealist story about a business man who unexpectedly turns into a flamingo (albeit one who still wears a tie and is still stuck in his established ways of thinking).

"The Afterlife of Ammi's Betelnut Box," Story by Iram Ghufran, Art by Ikroop Sandhu, with additional illustrations by Mitoo Das, gives us a glimpse into the Islamic culture of India.

Lakshumi Indrasimhan and Jacob Weinstein's "Tattoo" focuses on the expressive potential of ink and men's bodies.

In Pao's introduction, Sen also discusses there the properties of his medium:

"One could talk about 'engineering' comics in the sense that there is a lot of planning, craft, precision and labor involved. First, the superstructure of the narrative arc needs to be constructed with the raw materials that contain a mix of characters, locations, rationales and perhaps some random ideas and images. I try to make this strong yet flexible -- else the whole thing might collapse after I begin loading all of the other elements onto it. Then there is the building up of the chapters or sequences that determine the ebb and flow of narrative drama. Planning these bits is not unlike the way one would go about scripting a movie or a novel, I imagine. It is in the page planning and layouts that I feel I really begin to engage with the nitty-gritty of the medium. In comics, the turning of the page is the key act in the unraveling of the narrative. Hence, page break-ups and layout, text placements, etc., are aspects to which I pay a lot of attention. The final stage is the detailing of each frame, choosing angles and points of view, color, and light and shade. Though the entire process doesn't usually unfold in such a net way, I rely heavily on a hands-on understanding of this inner engineering of comics to respond to the unique challenges posed by each project."

Thinking of comics as a form of engineering strikes this former MIT faculty member as a very constructive way of thinking through both the production process and the challenges of conveying a narrative across words and images.

As an editor and community organizer, Sen clearly plays a central role in fostering the creative community in Delhi and in advocating on behalf of his medium across larger conversations in the arts world. I saw him struggle with what might be the best way for these artists to break out from their current ghettoization and command the kind of respect and impact enjoyed by their counterparts amongst alternative and independent comics creators in America or Europe. Sen argues that what they need to do is to produce a series of graphic novels, one after another, which can really put their scene on the radar of Indian readers. Right now, there are 1-2 books published per year on average, and so they are not getting the critical attention they require to become more firmly established. We joke about a “season” of comics, something that sustains the conversation across works and builds momentum and publicity over time.

They describe to me some of the comic-cons and comics festivals here in India, that place a strong spotlight on Indian comics. Sen and his collaborators seem very well connected with other international artists, describing, for example, being visited by R. Crumb who came to India to acquire more early 20th century records for his collection, and they seem to go often to international comics events but not yet to San Diego. We have a great time, sipping chai, and talking about our mutual love of comics.

During the conversation, I also learned more about the grassroots comics movement in India. Here, artists work to help students, farmers, local residents, anyone who wants, to translate their insights about the world into visual stories that can be reprinted and shared with a larger community. The emphasis of the grassroots comics movement is to help everyday people find their voice, to foster conversations around local problems and issues, by encouraging your friends, family and neighbors to look upon them in new ways.

The grassroots comics movement started in the 1990s and today, the World Comics Network, based in Delhi, runs training sessions and publishes some of the most promising output in newsprint for subscribers around the world. To date, the network has conducted more than 1,000 plus workshops in Asia, Europe, Africa, and Latin America, involving well over 50,000 participants, all of whom were empowered to draw the world they wanted to see. This video gives some sense of the energy and excitement they bring to this work

Another glimpse into the cultural life of Delhi:

Parmesh, Cynthia, and I are joined by journalist Nikhil Pahwa, who I had met eight or nine years ago when he visited MIT. He has been at the helm of the campaigns here in support of net neutrality, working alongside AIB (the comic troope whose video was widely circulated across India). So far, they have been very successful at mobilizing the public here to write the regulators in support of Net Neutrality. He says that because they were following the debates in the U.S., they got net neutrality into the conversation quickly and they have largely been able to frame the debate with the result that few directly oppose the principle but many corporations are nibbling away at the edges looking for ways that they can charge different users different rates and provide them with more or less bandwidth while seeming to support a broader grassroots access to the media. We have an animated discussion as we drive comparing tactics used in the U.S. and in India to get the public educated about what’s at stake with these issues. He says the sharpest critiques leveled at his group is the idea that the public is supporting these policies without really understanding them or knowing what the alternative arguments are, so they are making real efforts to educate their supporters so they can respond to questions from others.

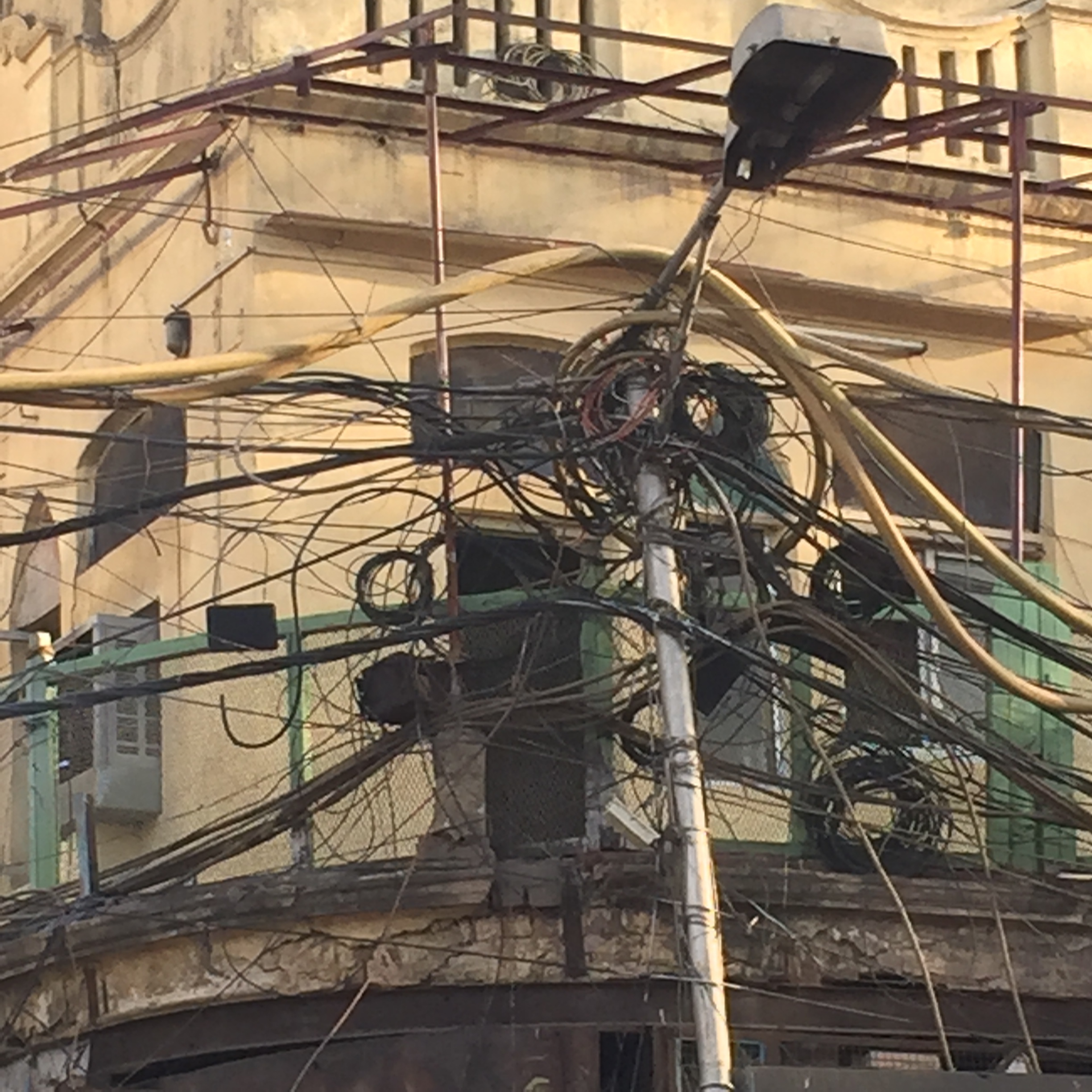

Nikhil is taking us to Old Delhi – the original city which was here before New Delhi was built. If New Delhi is highly ordered, a planned city, Old Delhi is one of the most chaotic and noisy places we’ve been in India (and that’s saying a lot). We hire two human-peddled rickshaws and we are ferried at a rapid pace down the street, weaving in and out of flows of traffic, involving motorcycles and auto-rickshaws, past little shops, piled high with goods or food stuffs. I am impressed by these incredible tangles of electrical wires which hang all over the buildings, basically a jerry-rigged infrastructure, constructed – mostly illegally – on top of crumbling ancient buildings. Nothing here would pass a code inspection in the U.S., that’s for sure.

And then we climb up the stairs, shed our shoes, and enter into the Jama Masjid, what we are told is the largest functioning mosque in contemporary India.

By now, it is late afternoon and the mosque is teaming with activity. There’s a large pool of water in the center, and people are gathered around to wash their feet and socialize. Over head, we see kite battles taking place and every so often, a kite gets severed from its cord (thanks to the success of a rival) and goes drifting off into the sky. We see such a wide array of different kinds of clothing here as Muslims come from all over the country and beyond to worship here. We are not here at prayer time, but we are told on high holy days that the courtyard will be completely full of worshippers bowing towards Mecca. We exit the Mosque and walk around the shop district a bit, but we are running out of time and still have several more stops to make today, so it’s back to the rickshaws and then down the street as fast as our poor guys can peddle, weaving in and out of traffic.

By now, it is late afternoon and the mosque is teaming with activity. There’s a large pool of water in the center, and people are gathered around to wash their feet and socialize. Over head, we see kite battles taking place and every so often, a kite gets severed from its cord (thanks to the success of a rival) and goes drifting off into the sky. We see such a wide array of different kinds of clothing here as Muslims come from all over the country and beyond to worship here. We are not here at prayer time, but we are told on high holy days that the courtyard will be completely full of worshippers bowing towards Mecca. We exit the Mosque and walk around the shop district a bit, but we are running out of time and still have several more stops to make today, so it’s back to the rickshaws and then down the street as fast as our poor guys can peddle, weaving in and out of traffic.