A New History of Laughter in China: An Interview with Christopher Rea (Part One)

/Christopher Rea's The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China offers an in-depth consideration of popular humor and popular culture more generally in China from the 1890s to the 1930s. This was a period of tremendous political and cultural change: many traditional forms of authority were challenged, and various forms of westernization and modernization impacted the daily lives of the people. Comedy feeds upon such instability: as the anthropologist Mary Douglas has suggested, jokes provide us a way to say things that are widely recognized or felt but can not be expressed directly. Rea looks closely at a range of different comic genres as he describes the ways that Chinese culture entered "an age of irreverence." I should be clear that I am no expert on Chinese history or culture, but I have studied what was happening to American humor and comedy during this same time period. My dissertation and first book, What Made Pistachio Nuts?: Early Sound Comedy and the Vaudeville Aesthetic, described the ways that the emergence of mass media and waves of immigration helped to shape what made Americans laugh in the first decades of the 20th century. Rea contacted me about his book because he saw some important parallels between the developments in these two different cultures at the dawn of the 20th century, and for this reason, I found myself drawn into this richly detailed, carefully argued, and theoretically nuanced account. I believe that the insights here have the potential to spark larger conversations about the cultural analysis of humor and comedy, so my interview here is designed to pull out parallels and differences between the place of comedy in China and the United States. We are planning to do a public exchange about comedy and cultural change at USC next term, so this is a good dry run for further explorations.

Let’s start with the title. Stereotypes of Chinese culture often include the idea of a deep respect for tradition, for seniors and for ancestors, which all grow out of the Confucian tradition. Yet, you talk across the book about “irreverence.” How and why did China enter an “age of irreverence” and how might we understand what “irreverence” means in a Chinese context?

Respect for tradition and convention was still a strong part of Chinese culture at the turn of the twentieth century, but the top of the social and political hierarchy was breaking down. Qing armies had been defeated by the British in the Opium Wars, routed in the south by Taiping rebels (whom it took them 14 years to eradicate), and, in the 1890s, humiliated by the Japanese. Han Chinese resented the Manchu court, which was increasingly dysfunctional and desperate. Plus, you had a huge supply of frustrated, educated men who had trained for the civil service but had no chance of getting a government job. In the past they might have turned to tutoring for a living, but now many went to work for the expanding periodical press, which gave them a new platform to share erudite jokes, write doggerel verse, parody government proclamations, or trade insults. At the time, to express reverence for authority or for Confucian wisdom was anachronistic. You’d make yourself a figure of fun, cynicism, or even contempt.

The founding of the Republic of China in 1912 brought new hopes, but those soured immediately when the former Qing general Yuan Shikai pushed Sun Yat-sen aside and made himself president. Yuan sounds like “ape” (yuan) in Chinese, and a new crop of cartoonists and satirists had a field day with a strongman aping a statesman (figure below).

“Dreaming of the Central Government.” Yuan Shikai as an ape reaching for a tablet that says “Long Live the Emperor.” Civil Rights Daily (ca. 1912)

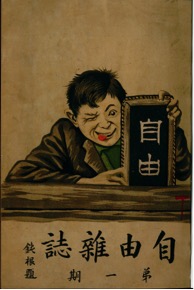

This cover from the first issue of Free Magazine (Sept. 1913), a spinoff of the Shanghai daily Shun Pao’s “Free Talk” column, symbolizes a moment at which the press was celebrating the “freedom” (the word the boy’s holding) to be irreverent.

Cover of Free Magazine (issue 1, Sept. 1913), a spinoff of the “Free Talk” column of the major Shanghai daily Shun Pao

Long story short, the outburst of irreverence was caused by a combination of disastrous national politics, uneven censorship, new mass media platforms, and people motivated to take advantage of these opportunities to change the tone of public discourse.

You talk about the book as a “history of laughter,” by which you seem to mean both a history of genres of popular amusement intended to provoke laughter and a history of the emotion and bodily reflex we call laughter. Can you say more about what it means to develop a history of laughter as opposed, say, to a history of comedy?

Xiaoshi, is a phrase I kept coming across while reading Chinese periodicals from the late 19th and early 20th century. “History of Laughter” is a literal translation of xiaoshi, which could also mean “laughable tale,” “funny story,” or just “funny stuff.” It was print industry shorthand for “Humor Here!” Editors called joke collections, novels, news items, stories, celebrity and political gossip all xiaoshi. They even applied it to a translated 1930s comic strip featuring the silent film comedian Harold Lloyd, who for a while was a bigger star in China than Chaplin. With “History of Laughter” we’re dealing with a genre of affect rather than of form. Part of my reason for using that term is to call attention to this Chinese convention, which predated but got a big boost from a boom in periodical publishing that occurred during the early twentieth century.

My subtitle is “A new history of laughter in China” because modern joke-writers tried to give their products a leg up in the print market by slapping on the term “new” or “modern.” (figure below) Be New was the big modern imperative, though a lot of the jokes that appeared under the New History of Laughter banner were recycled. This is no big surprise—you find the same thing going on in 19th-century Europe and America.

Utterly Brilliant and Delightful Modern Jokes (1935)

But it does mark a cultural shift. Now you had a broad print culture that thrived on emotional payout. Historians of the era have tended to emphasize the prevalence of tears, sympathy, and other forms of catharsis. In China, this is partly because the Communist Party has, since the success of its revolution in 1949, promoted the Republican Period and the late Qing era before it (roughly, 1890s-1949) as an Old Society of pain and suffering. The era is also replete with laughter, much of which I see as expressing a modern attitude of open, even mocking, skepticism.

My main goal is not to answer the question “why do we laugh.” It’s to identify Chinese genres (including some we might call “comedy”) and sensibilities and show how they changed in the modern era. I focus on five Chinese terms that dominated the humor market in the early twentieth century: xiaohua (joke/humorous anecdote), youxi (play), maren (mockery/ridicule), huaji (farce), and youmo (humor). Starting with this basic lexicon, I show why, for example, the humorous curse became such a conspicuous part of 1920s literary culture, when the promise of a cultural renaissance was eroding due to warlord violence. Or why foreign-educated Chinese promoted a tolerant, worldly, empathetic sense of humor—they saw it as a way to purge their countrymen’s deep-seated cynicism. The Age of Irreverence is partly a history of the Chinese language, so I do pay close attention to semantics, but it also goes beyond that to look at the politics of being funny in a modernizing society.

Christopher Rea is an associate professor of Asian studies and director of the Centre for Chinese Research at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. He is author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History of Laughter in China (California, 2015); editor of China’s Literary Cosmopolitans: Qian Zhongshu, Yang Jiang, and the World of Letters (Brill, 2015) and Humans, Beasts, and Ghosts: Stories and Essays by Qian Zhongshu (Columbia, 2011); and coeditor, with Nicolai Volland, of The Business of Culture: Cultural Entrepreneurs in China and Southeast Asia. He is currently translating, with Bruce Rusk, a Ming dynasty story collection called The Book of Swindles.