Geeking Out About The Comics Medium with Unflattening's Nick Sousanis (Part One)

/

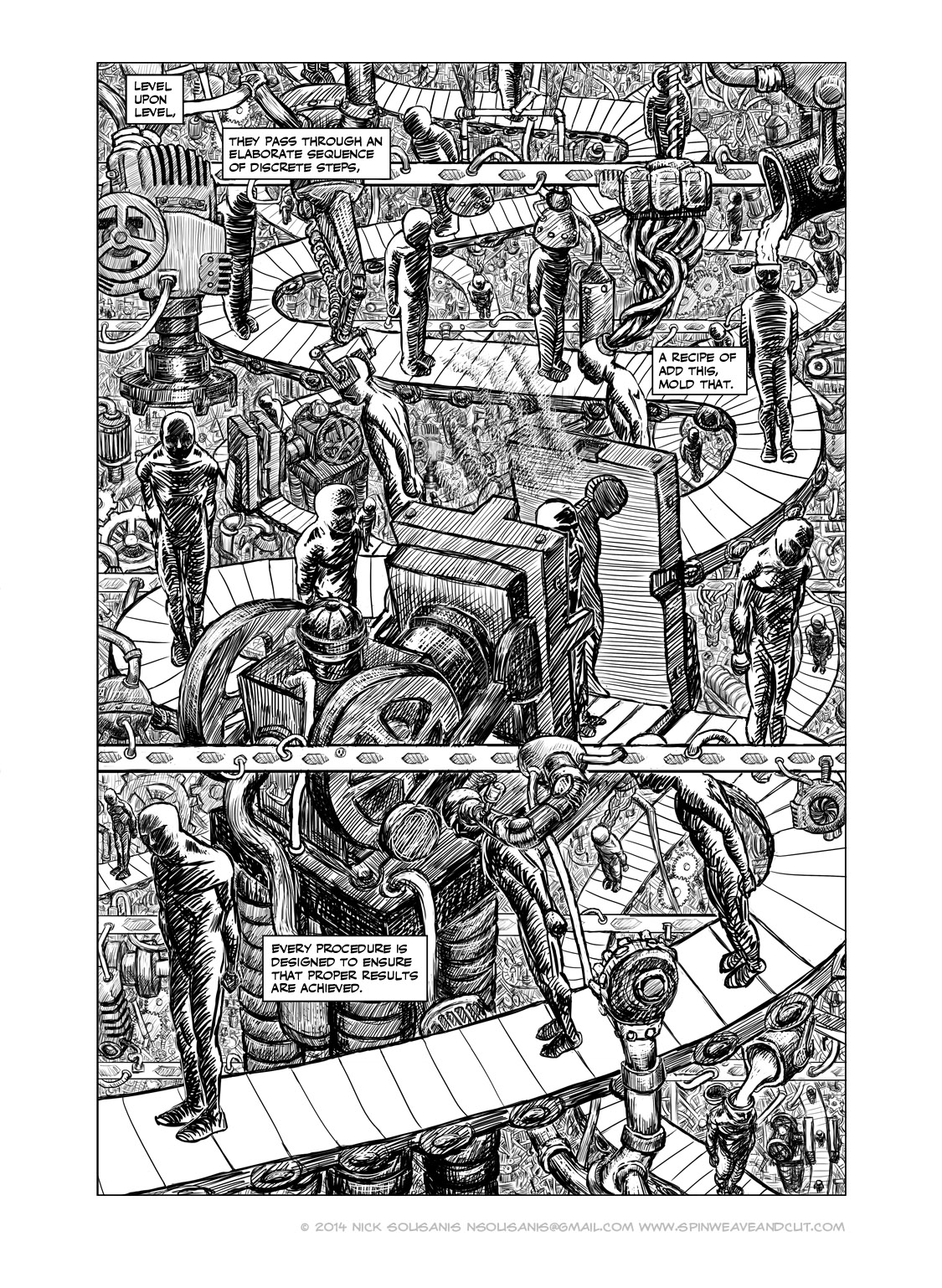

About a year ago, I was asked by the Harvard University Press to be a peer-reviewer for a remarkable book -- Nick Sousanis's Unflattening. I had heard rumors that a PhD candidate had written his dissertation entirely in the comics form and I was intrigued to see what the finished product looked like, perhaps skeptical that it could be good on both levels -- good scholarship and more importantly, good comics. So, I was unprepared by what I was sent -- this was not simply good comics, whatever that might mean, but transformative comics, comics that stretched the medium in all different directions, comics which made us think about comics were in new ways. On one level, it reminded me of my experience first reading Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics, but it also got me thinking about those comics artists whose expressive use of the medium taught us to rethink what comics are implicitly if not explicitly -- Chris Ware, Will Eisner, David Mazzuchelli, David Mack, Richard McGuire, Art Spigelman, etc.

So this is what I ended up writing (and after several more reads, I stand by it):

“An important book, Unflattening is consistently innovative, using abstraction alongside realism, using framing and the (dis)organization of the page to represent different modes of thought. The words and images speak for themselves and succeed on their own terms. I couldn’t stop reading it.”

So, when the book appeared, I reached out to its author and asked Sousanis if he would subject himself to an interview. Again, he has surpassed my expectations. What follows is a four part interview where the two of us really geek out about comics as a medium and about its unfulfilled potentials. He has interesting things to say about specific pages in Unflattening, but beyond that, we take up what comics may do to expand human perceptions and thoughts (yeah, heady, thinky stuff!) and beyond that, about the potentials and limits of multi sensory expression. Fastening your seat belts, dear reader, for a bumpy ride. And as Nick noted, he ended up putting almost as many words on the page here as appears in the book itself. What follows is not just for comics fans, though, but for anyone who is interesting in exploring how media work.

You write, “a changed approach is precisely the goal for the journey ahead: to discover new ways of seeing, to open spaces for possibilities, and to find ‘fresh methods’ for animating and awakening.” To what degree are these goals you are setting for comics as a medium? To what degree are these goals you are setting for academic writing more generally?

As with most things in the book, my intention was two- or more-fold. The choice to work with metaphorical language and imagery let me address something at once specific but leave it open to other interpretations. Here, I definitely wanted to make the claim that changed approaches for academic work and institutional approaches to learning were possible and necessary. That the visual, among other things, had a place in being a part of what thinking looks like and that by embracing such methods, we might arrive at a changed place in how we do our thinking. I do, of course, taking up comics specifically at some point. And so, I think in this way, the work itself is very much setting out to reframe the perception of comics. Even if we had known comics can handle serious stories for a long time now, I wanted to say with this work – comics can handle anything in any domain.

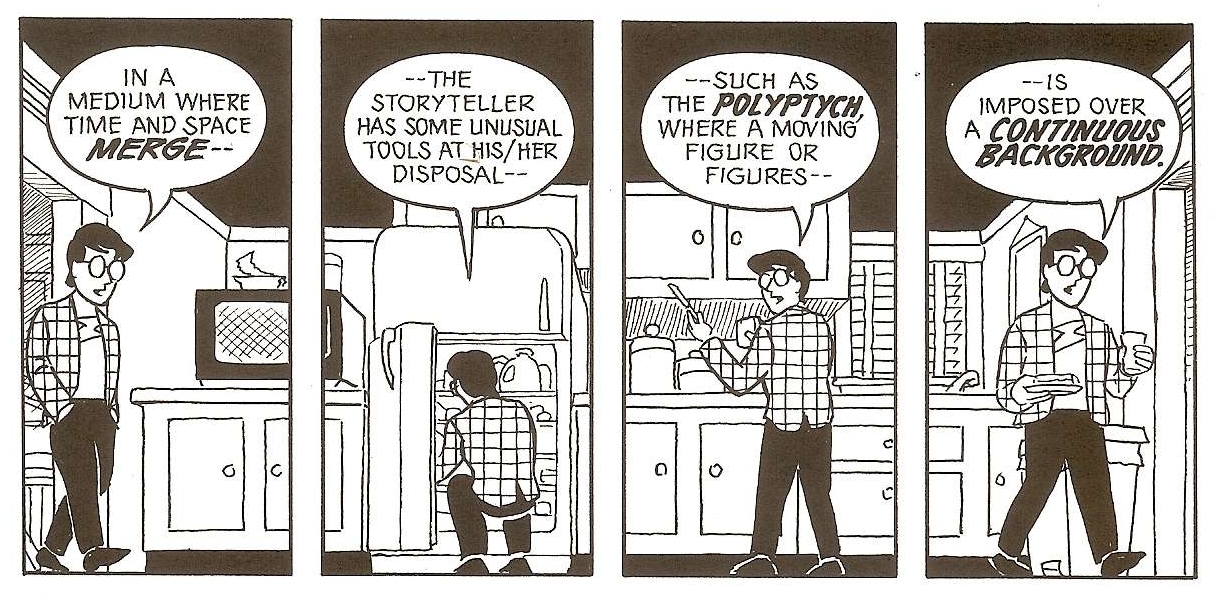

Your opening critique of life lived within confined and preset grids can be as much a critique of many contemporary comics as it is an analogy for the limits of human expression and experience more generally. Clearly, your work has been inspired by Scott McCloud’s call for us to think of comics as a more generalized mode of expression which can convey a variety of ideas and concepts, not simply a limit number of genres and formats. So, in what ways did McCloud’s Understanding Comics pave the way for a project like this one?

While I hadn’t intended for that talk of boxes to directly reference comics, I appreciate the irony of discussing moving outside of boxes even as I work in a form that tends to be defined by organizing within boxes! J (Though I have in the past made comics that played with the concept of boxes using the literal nature of comics panels to make that point.)

Understanding Comics certainly had and continues to have a significant impact on me, as has McCloud’s inspiration as a champion of the form more generally. I think you’re exactly right, it pointed out that comics could tackle all kinds of subjects and not be limited to narrative genres, and really it showed both how much thought went into making comics and how much thinking could be conveyed through them. That inspired me, and certainly emboldened my own explorations. And Understanding Comics is an obvious thing to point to as precedent when making the argument for my own work – as I hope Unflattening might be for scholar-artists to come.

You’ve said in a number of interviews that you wanted to use Unflattening to help broaden the circuits through which academic ideas travel, so that these conversations were able to reach people who would not otherwise encounter scholarly or philosophical works. What is it about comics which seems to open up those possibilities and based on what you’ve observed so far about your book’s reception, have you found a general reading public ready to think of these levels? Does this link your book to other contemporary projects, such as work to convert ideas about film analysis into videos that circulate on YouTube?

Certainly comics offer the appearance of approachability. Pictures are inviting and the prevailing attitude around comics are that they’re easy. I see this as a means to subvert expectations – you pick up one of my comics assuming it will be simple and light, and yet because of how much information can be conveyed through images, through page composition, and through the interaction between image and text, they can be deceptively complex. While the title “Unflattening” must seem like it came about as a reference to Flatland or Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man, works I do draw on heavily, it actually came to me as a way to describe what comics could do, and how they could fit more density of information than seems possible in a small space and offer an expansive dimension for communicating ideas. It was only as I got deeper into my work that the notion of unflattening merged with the broader philosophical concerns I was after. The inclusion of Flatland at all was almost an afterthought, because I figured given the title I should do something with it, and then it ended up becoming a central metaphor!

In addition to blogging my work as I went, all through my doctoral program, I printed up and gave away excerpts of it to anyone I encountered long enough to have a conversation about what I do. People read it. And they got it. And that has continued. I’m thinking I couldn’t have done the same thing with a more traditionally formatted scholarly article! (The looks I would’ve gotten handing out a typed paper with APA formatting on it…)

But again, that doesn’t mean any of this was simplified. I made a conscious choice early on to not use domain specific terms or what felt like loaded language, and keep the work deeply in the realm of metaphor. This to me was a way to make it more accessible while maintaining depth of content. It was not about dumbing down but providing a means for readers to come up and find their own way into the work. And again, I’ve seen that happen.

And now that the book is out, I’ve had the curious experience of having people tweet me pictures of their children – one as young as six – reading it! That caught me by surprise. I expected it to be read by advanced high school readers and upward (and along with college and graduate courses, it is already being used in high school situations). But I think this speaks to the ways that we can read images – even when the words aren’t yet in our vocabulary.

I have seen my work listed alongside the “dance your dissertation” and other such phenomenon of academia made fun or easy. I like these – anything that communicates the ideas to broader audiences seems positive to me. But it was central to me that the work be the work – not some watered down version of the real thing. If the means of communication are truly up to the task – as I was certain that comics were – then it’s essential to let them stand on their own.

Nick Sousanis received his doctorate at Columbia University, where he wrote and drew his dissertation entirely in comics form. Titled Unflattening, it is now a book from Harvard University Press. He’s presented on his work and the importance of visual thinking in education at such institutions as Stanford, Princeton, UCLA, and Microsoft Research, along with keynote addresses for the Visitors Studies Association’s and the International Visual Literacy Association. He has taught courses on comics as powerful communication tools at Columbia, Parsons, and now at the University of Calgary, where he is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow in Comics Studies.

Nick’s website: www.spinweaveandcut.com