Participatory Politics in an Age of Crisis: Melissa Brough and David Nemer (Part II)

/Melissa

I completely agree with you that it is “magical thinking” that social media would bring more social equity. As I discuss in Youth Participation in Precarious Times (forthcoming, Duke) the Web 2.0 (and some digital media scholars’) version of “participatory media” was technologically deterministic, assuming that a platform that could be used for participation would necessarily promote meaningful participation. In other words, it anthropomorphized internet technology by ascribing a social behavior to it. While the unprecedented access, interactivity, networked distribution, and speed of internet, mobile, and Web 2.0 technologies have reduced barriers to communication and participation for many of us, the history of participatory communication -- e.g. community radio; community television; participatory theater; participatory art; etc -- around the world (including in Brazil) problematizes this attribution of participation and equity to social media.

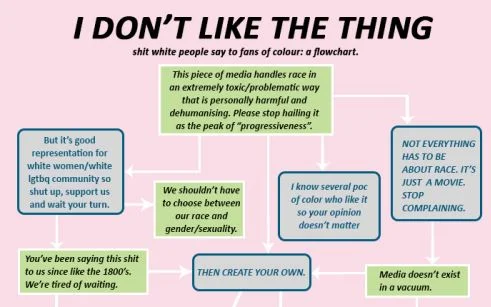

I’m also drawn to your examples and analysis because they illustrate how grey the spaces between hegemony (like social exclusion / racism) and resistance can be -- often, the two are operating simultaneously and may even be intertwined. One person’s act of resistance may be another person’s reaffirmation of a social hegemony, and vice versa. Certainly, participatory politics is not only the playground of progressive social justice advocates.

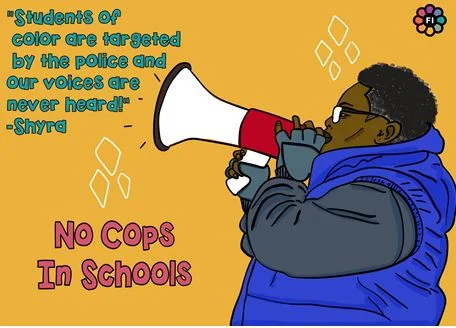

Your examples underscore the need for greater emphasis on cultivating the skill of listening (and ‘moving over,’ to borrow from feminist critique). Western (especially U.S.) culture incessantly places emphasis on ‘voice’ in a way that often over-values the expression of individual voice at the expense of the equally -- if not more -- important need to deeply listen to the experiences of others. Mainstream social media culture has only exacerbated this. It’s primarily about “broadcasting yourself” (YouTube), with very little discussion of listening to other voices. Organizations and projects like Global Voices and Witness offer important exceptions to this.

I wonder, do you think the Brazilian cases of participatory politics have anything to teach those of us in the global North about cultivating cultures of listening?

David

I really appreciate the cases you bring to the discussion, Melissa, as they push us to think outside the Western norms of participatory politics and social media use. You hit the nail on the head when you claim: "what has made media participatory was how they were used and by whom, not the technologies themselves"- and that's exactly what I have noticed in the favelas of Brazil, especially in the case of the Protests of 2013. Even though the marginalized were not able to actively participate in defining the agenda of these protests, they helped these demonstrations grow to something the country has never seen before. The protests were still sounding progressive, a bit inclusive and nonpartisan, where people were demanding from politicians better schools, health care, an end to violence and corruption. I have to confess that I did have some hopes for better days after my first experience following the protests. However, looking at what is currently happening in Brazil, given the election of Bolsonaro, the question that I have been exploring is: how did Brazil go from social demonstrations in 2013 that seemed progressive and nonpartisan, to today, with an impeached left-wing female president to a far-right white man as president? (I think the answer to this question connects very well to your question about what can be learned from participatory politics in Brazil).

In my understanding, many things happened, but one in particular caught my attention: as I was doing follow-up fieldwork in 2014 and 2015 when I observed the rise of extreme groups and leaderships that piggybacked on the enormous sense of change to skew the discourse of these protests. They brought rhetorical claims such as that the political class, or the establishment, didn’t represent them, that the common men were being crushed by political correctness and bureaucracies in order to get the protesters' sympathy. Extreme groups are somewhat known to do that, for example they have piggybacked on the Occupy Movement to promote the idea of the forgotten white common men, and we are currently seeing a very similar phenomenon with the yellow vests protests in France.

Paulo Freire (2018) once said that "certain members of the oppressor class join the oppressed in their struggle for liberation, thus moving from one pole of the contradiction to the other. Theirs is a fundamental role, and has been so throughout the history of this struggle." The oppressors or exploiters, in this case the far-right groups, as they join the people in protests, they bring their prejudices and their deformations, which include a lack of confidence in the people’s ability to think, to want, and to know, to take over the leadership of these movements in order to make the demands about what they (far-right groups) think is best for the country, or for themselves.

The interesting thing is that these extremist groups in Brazil, disguised as non-partisan, took advantage of their tech savviness to engagement with new media to recruit and convince new members, and kill any attempt to deconstruct their groups on social media. These groups, such as MBL (Movimento Brasil Livre), started on Facebook, with the spread of sensational short clips and memes. In 2016, with the decline of new users on the platform, they moved their channels of communication to YouTube, and then finally, in 2018, during Brazil’s elections, these groups moved to WhatsApp where they were able to join organically built WhatsApp discussion groups in order to pass on their ideology (see my article in the Guardian).

As we acknowledge these events, I'm left with many questions and very few answers: how do we protect progressive participatory politics and protect them from extreme groups? How can we promote digital literacy and skills for an empowering participatory media and not an oppressive one? Is "participatory" just an illustrative term where in fact we actually need some sort of higher level command to protect the participants from extreme forces? All I know is that, based on my research, the solution will not be found in technology, but in the voices and actions of people who still believe in a more inclusive future. However, to move forward, we have to understand the depths of the desperation that members of extreme groups have tapped into, and given voice to, in their own conceptualization of participatory politics.

Melissa

I’m so glad you brought up the need to “understand the depths of the desperation” experienced across all points on the political spectrum. At the end of the day, participatory politics is just another way in which individuals and groups are expressing their hopes, fears, pain, and desires. Perhaps one small way forward is for all of us to work on being better listeners, and on respecting and holding space for the individual and collective experiences of fear and pain that are currently polarizing societies worldwide, as we work to transform the underlying structural and cultural dynamics causing them. Thank you, David, for this conversation!

David

Absolutely agree, Melissa. Thank you for this enlightening conversation.

___________

Melissa Brough is Assistant Professor of Communication & Technology in the Department of Communication Studies. Her research focuses on the relationships between digital communication, civic/political engagement and social change. Much of her work considers the role of communication technology in the social, cultural, and political lives of youth from historically disenfranchised groups. Her research has been published in Mobile Media and Communication, the International Journal of Communication, and the Johns Hopkins Guide to Digital Media, among others. Her book Youth Participation in Precarious Times: The Power of Polycultural Civics is forthcoming from Duke University Press.

David Nemer is an Assistant Professor of Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His research and teaching interests cover the intersection of Postcolonial Science and Technology Studies (STS), Information Anthropology, ICT for Development (ICT4D), and Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). Nemer is an ethnographer whose fieldworks include the Slums of Vitória, Brazil; Havana, Cuba; and Eastern Kentucky, Appalachia. Nemer is the author of Favela Digital: The other side of technology (Editora GSA, 2013). He holds a Ph.D. in Informatics (track Computing, Culture, and Society) from Indiana University and an M.Sc. in Computer Science from Saarland University. Nemer has written for The Guardian, El País, and The Tribune.

![“DEWmocracy” on Facebook. [Source: https://www.facebook.com/DEWmocratic/]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/592880808419c27d193683ef/1557856097521-C9NJZGLNCEU5T5UX0CND/Capture.JPG)

![Santo Domingo Library Park and metrocable, Medellín, Colombia. [Source: http://www.nomads.usp.br]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/592880808419c27d193683ef/1557856181260-W7H287J93C385S16UY7A/Capture.JPG)

![Members of youth-led hip hop collectives in Comuna 13, Medellín, Colombia. [Source: author]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/592880808419c27d193683ef/1557856249722-FBAFE3OCVPPNCJU1FZMM/Capture.JPG)