Learning in a Participatory Culture: A Conversation About New Media and Education (Part Four)

/This is the final part of my interview with Spanish educational researcher Pilar Lacasa for Cuadernos de Pedagogia, a Spanish language publication, about my research on the New Media Literacies. Here, we discuss learning games, mobile technologies, civic engagement, and my advice to parents and teachers. Our challenge is then building bridges between culture and participatory democracy. Can you explain more?

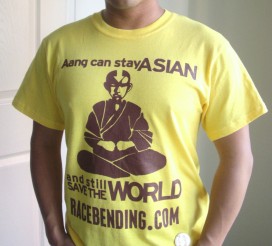

The challenge is how we can help build the bridge between participatory culture and participatory democracy. I am starting to do research on what I see as proto-political behavior: the ways that these hobby or fan or game groups educate and mobilize their members around issues of collective concern. I believe that if we better understand these practices, we will be in a position to foster a new kind of civic education which starts where young people are already gathering but helps them to expand their understanding of their roles as citizens. A striking feature of these new social structures is that they are defined less through shared geography than through shared interests.

They may be better suited to support national or even global models of citizenship than those based on purely local levels of engagement. Yet, we need to be careful about making too many hasty assumptions about this. Jean Burgess tells the story of photographers in Queensland who connected through the photosharing site, Flickr. They began meeting up on weekends to visit local sites and photograph them together. As they began to share these photographs, they connected with former residents of the region who now lived elsewhere who shared older images and stories and remain linked to the local through the platform. As they began to take photographs, they began to look at their community through new eyes, starting to identify local problems and eventually working together to increase public awareness and lobby for solutions. So, a platform which is not particularly local in its organization never the less resulted in local political engagement.

You say that these on-line communities could be a new way for people practice being citizens. Could you explain these ideas a little further?

Robert Putnam's book, Bowling Alone, sees bowling leagues as a cornerstone of American civic life in the 1950s. He suggests that communities gathered regularly at bowling allies to spend time together, increasing the social connections within the community. When they were not bowling, they were engaged in conversations -- some simply gossip, others dealing with local policies and concerns. The strong social ties which emerged in this context helped to strengthen their collective identities as citizens and thus increased voting and public service. Putnam fears that television pushed Americans out of the bowling allies and into their private homes, resulting in much greater social isolation and a breakdown of community life.

So, how do we understand the new social structures which are emerging around online gaming -- the guilds in World of Warcraft, for example. Here, people form strong shared identifications, gather together regularly to play and socialized, develop leadership which can deploy the diverse skills of the guild membership to confront complex challenges and pursue long term and short term goals. Often players say they come back night after night out of a sense of obligation to each other as much as out of a pleasure in the game play. In short, there are many of the foundations here which Putnam argued allowed bowling to seed a robust civic culture in the mid-20th century.

And video games? What can children learn from them?

Will Wright, the designer behind Sim City, the Sims, and Spore, has suggested we think of games as problem sets which students pay to be able to solve. What he means is that a good game poses complex challenges which are just on the threshold of the player's abilities, creates a set of scaffolded experiences through which they acquire the knowledge and skills needed to solve those problems, and offers them a chance to rehearse, make mistakes and learn through them. An even stronger game allows them to manipulate the simulation, shifting variables and learning what the consequences of their changes are. A great game creates a context where they are encouraged to share what they learned and what they produced with other players, enabling peer to peer learning to occur.

As James Paul Gee has suggested, games put into action many of the core principles being discussed by the best work in contemporary learning sciences. And they do so in ways that are highly motivating. Young people have clearly defined goals and compelling roles which motivate them to actively and intensely engage in the learning process. We've all seen kids who will quit early when they hit a problem with their homework and yet beg to stay up later if they hit a challenge in a game.

Could then video games have a place in classrooms?

Schools would do well to see what they can learn from games. Some are arguing that schools should build activities on and around existing commercial games which already have strong learning potentials; others that educators should be developing compelling new games which connect school content with good game design; and others are suggesting that we redesign school activities to include elements of play and game design. All of these models point to the need to incorporate a more playful mode of learning into our educational institutions and to harness the power of games for more formal kinds of education.

Right now, games are teaching young people skills -- problem solving, design, simulation -- but it is up to teachers to couple those experiences to specific domains of knowledge which get valued in the curriculum. My experiences in developing educational games suggest that the first step is trying to rethink why we want kids to learn what they are required to learn -- that is, what it allows them to do in the world. Because information that is latent in a textbook has to be deployed actively in a game, otherwise there is no learning taking place.

Do you think video games can help break down barriers between what is learned inside and outside school?

Playing the game is only a small part of gaming culture and in the case of The Sims, Spore, or Little Big Planet, it may be the least significant part of the experience. These games encourage young people to remix and reprogram their contents. Sims players may develop their own avatars, design their own furniture, and exchange it online at the Mall of the Sims. The Sims players may use an ingame camera to collect images for their scrapbooks and then use the images to construct original fictional narratives. They may use the game engine as an animation platform to construct their own movies. In Little Big Planet, they may design and program their own levels and exchange them with other players. In many games, they form communities online to teach each other the skills they need. And in games like the Civilization series, which simulate historical societies, they include teaching about real world history as well as ingame strategies and tactics.

In each case, the game becomes the entry point for a broader range of cultural expressions and in the process, helps to create sites of learning. Young people are learning to program, design, tell stories, or become leaders through their social interactions through and around games. These accomplishments need to be recognized and valued through schools just as schools have historically supported the activities of Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts or after school programs like yearbook, newspaper, drama club, and the like. These activities become a crucial part of how young people define their identities and form social affiliations.

But the principles that work there to support informal learning can also be carried over into more explicitly educational activities. For example, Mitchell Resnick at the MIT Media Lab has developed the Scratch program which uses these same participatory culture principles to enable young people to learn how to program; they've created a platform where young people develop their own projects, share them with each other, borrow and remix codes, building upon and improving each other's work, through principles derived from the Creative Commons and Open Software movements. Young people around the world are using these platforms to acquire digital skills through the classroom, after school programs, and on their own.

I would like to ask you about the context of learning related to the new mobile media, for example a small NDSi or the iPhone. What implications could have this have for education?

In many parts of the world, these new social and cultural practices are developing around mobile media rather than networked computers. Cell phones are dramatically cheaper than laptops, say, and thus we are broadening who gets to engage with the new social networks. Twitter, for example, is designed to allow contributions from both mobile phones and computers, creating a system where information flows fluidly across media platforms.

A short term consequence of these developments is that young people will be able to access the information they need from anywhere and everywhere. These mobile phones will become a new kind of knowledge prosthesis which expands the capacity of their memory, allowing them to mobilize information in new ways on the fly. We call these practices distributed cognition because they involve off-loading parts of our thinking capacity onto a range of appliances and see it as a fundamental literacy.

Of course, we need to be concerned about an over-reliance on such devices if it decreases other kinds of learning, yet we also need to know multiple ways of solving a problem and the ability to off-load some tasks to our tools makes it possible for us to explore other questions at greater depth. Yet we are just starting to explore the implications of location-awareness for education. Eric Klopfer at MIT has developed a tool kit which allows educators to design augmented reality games. Augmented reality games are played in real spaces using digital handheld devices. In some cases, they allow students to access fictional information which is GPS enabled alongside their own observations of the real world.

Through the games developed for these platforms, young people learn to see the world through the eyes of urban planners or environmental scientists; they get to see their local communities as they might have been a hundred years ago. David Williamson Schaffer talks about these practices as "epistemic games," that is, games which help us learn to think like a particular professional group, deploying their real tools and practices to confront authentic problems in the real world.

Young people may not simply play such games; they might also work to develop them, interviewing people in their neighborhoods as they build games around local history or civic problems, translating what they learned in their textbooks into resources which they can deploy on the ground to solve compelling problems.

What aspects do you consider to be essential in teacher education to help kids and young peopleto develop new literacies by using these new media?

Teachers, librarians, and other educators have a vital role to play in this new electronic culture. They will become research coaches who help young people set reasonable goals for themselves, develop strategies for tracking down the information they need, advise them on the ethical challenges they confront as they enter new social and cultural communities, and recommend safe ways of dealing with issues of publicity and privacy which necessarily shape their digital lives.

In order to perform that role, they have to become comfortable with the new technologies and their affiliated practices. It is not enough to know how to use the tool; they have to master the cultural logic and social norms which are emerging around these online communities. This is too much for any teacher to take upon themselves. So, they must each take responsibility for acquiring different skills and understandings and be prepared to draw upon each other as resources for themselves and for their students. In doing so, they will be applying the principles of collective intelligence and social networks to their own practices and thus will be immersing themselves more deeply in these new media literacy skills.

We've been experimenting with an 'unconference' model for developing curriculum which bridge between traditional school content and new media literacy skills as an alternative model for professional development. The unconference starts out fairly chaotically as participants dump onto the web or exchange in person ideas, resources, practices, and activities which they think might be valuable to this subject area. Gradually, you gather together these resources, start to construct categories, and refine the activities. In the process, participants get to know each other and what each member can contribute to the group.

Many families are afraid of new media, and may even prevent their children from using them in the same way as they use a book, or a comic, a novel and so on. What would you say to them?

In many ways, parential concerns about new media are understandable. As parents, we are facing new experiences which were not part of the world of our childhood. We don't know how to protect our children as they enter these spaces and we may not know how to advise them when they encounter problems there. But those basic concerns can easily be turned into fear and even panic as they get manipulated by a sensationalistic press , political demagogues, and culture warriors. As adults, we owe it to our children not to foreclose important opportunities out of ignorance and fear. Instead, we have an obligation to learn more about the emerging cultural practices we've been talking about here. I certainly don't think we want to turn our backs on our children nor do we want to be snooping over their shoulders all the day. We need to be informed allies who can help watch their backs as they enter into situations that none of us understand fully.

We need to be there to celebrate their accomplishments; we need to be there to advise them as they confront ethical challenges; we need to be there as they acquire skills at accessing and deploying information. We need to do this because it is important to our children, their development, and their well-being.

Maybe you can tell a little more by using some example

Here's a few practical examples of things you can do: When my son was three, my wife and I began to help him develop some basic media literacy skills. Some nights, we read him a bedtime story. Other nights, we asked him to tell us a bedtime story. We recorded his stories on the computer; we could print them out and let him illustrate them, then we'd photocopy the whole and send it to his grandparents as a gift. They would read and respond to his stories. Many of his stories dealt with the media he consumed -- games, television, comics, films, toys -- and we would use this storytelling practice to talk through with him his fantasies and fears, sharing our own values about the issues he was exploring.

Telling the stories gave him a sense of being an author -- a key experience as we think about the new participatory culture -- and it paved the way for later creative experiences he would have as he moved on line.

Or imagine an older child -- a teen or preteen -- who is first becoming interested in social networking sites. Perhaps you could ask her advice in setting up your own Facebook page. This would allow you to learn more about how social networks work but also to create a context for talking about how people represent themselves on line. If she's like most teens, she is going to be at least as concerned about being embarrassed by her parent's public presentation as you are going to be about how much information she shares on line and it is through those conversations that you can exchange your values.

Teens still need adult involvement and parential advice as they move into this new world, but they also deserve to have that advice informed by direct experience and careful research into the nature of the world we are preparing them to enter. This is no different in its logic than what previous generations of parents have faced given the pace of technological change across the 20th century, even though the specifics are going to be different from anything your parents confronted in raising you.

In conclusion: How can we transform schools by using new media? Please, give us one or two suggestions for institutions, even governments, that are considering this challange, what would you say?

The first point I'd make is that we have to understand the new media literacies as a paradigm shift which impacts every school subject, not as an additional subject which somehow has to be plugged into the over-crowded school day. The push should be to have every teacher take responsibility for those skills, tools, and practices that are central to the way their disciplines are practiced in the real world rather than locking away the technologies in a special lab or a special class where it gets isolated from the real work of the school. The school needs to work together, as a community, to develop strategies for full integration across the curriculum, and to identify those skills which each member might contribute to the community as a whole.

Schools need to operate much more along principles of collective intelligence and social networking -- to identify and deploy the expertise they have in their community and to reach beyond their community to other sources of experience and knowledge, whether parents, educators at other schools, or others within their larger community. They need to create ways of sharing best practices and failures, offering advice and feedback to each other as they make this challenging transition. They need to be as concerned with how they teach as they are with what they teach.

Where possible, schools need to introduce complex problems which require their students to track down information from multiple channels and to work together to pool knowledge and combine skills . They need to develop opportunities for young people to share what they have produced with the world, getting feedback and recognition from a larger community, and taking greater responsibility for the quality of information they circulate.

Schools need to lower existing barriers which make it difficult to deploy participatory platforms through education, stepping back from software that filters or blocks access to the internet. But in doing so, they also need to work with the students to develop norms of use that respect the particular character of the school community and its goals rather than adopting an "anything goes" attitude.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=00d28f2c-accc-4de6-8ee0-5b768f5a8890)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=32c2f2db-1482-4b34-9502-4e2c841ae0b7)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=91bbb21f-52c0-4293-a57b-4218a799a45b)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=ec053f8e-cbb2-4747-bf27-39128120381b)