The Future of Teenagers: My Interview in O Globo

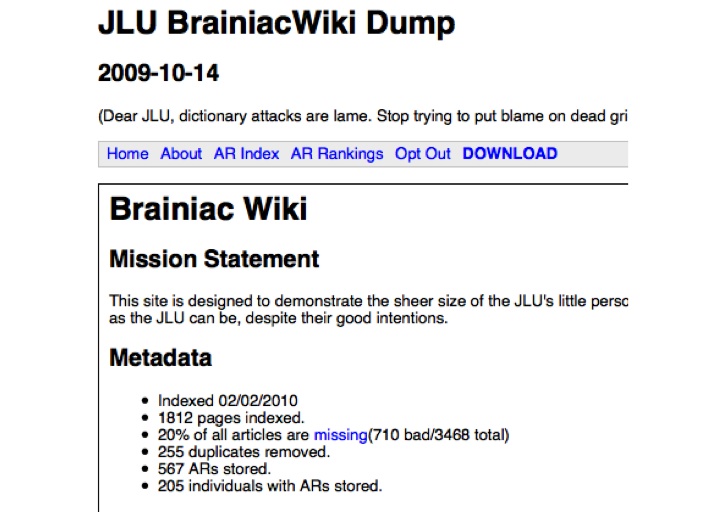

/Here is the interview I did with Bruno Porto of O Globo, a publication targeting youth, during my time in Rio. The newspaper devoted three full pages to this interview which was prominent on its cover and I heard lots of great responses to it as I traveled around the country. I suspect what will be striking to readers in the United States is how much the questions being asked there by parents, teachers, and others about new media are very much those being asked in our own country. For those who prefer to read this in Portuguese, here's the link. What´s the main difference between the teenagers that lived in 2000 and the ones that live nowadays? Do you see them as completely different beings or the prior generation already had cultural elements that are present in the next one?

First, the continuities across generations are much greater than the differences. Young people today listen to different bands and often acquire music through different platforms than teens a decade ago, yet one's taste in music is still a key indicator of one's personal and social identity for teens. Young people play different games on different game platforms yet young people acquire and display mastery through competitive play. Young people use different social networking platforms and communicate with their friends through text-messaging, yet forging a place for oneself within the social system of their schools remains a central goal of adolescence. We can go down the list and most of the new digital practices which seem alien to older people are serving purposes which, if they are being honest, they recognize from their own teen experiences. That said, there are also significant differences, which I know we will get to as this interview goes forward. What does it mean to have immediate contact with your friends as a support system as you move throughout your day, to know that you will remain connected with your friends no matter where you move in the planet, and that you can form intense, intimate social ties with people who you may never meet face to face? Or to know, but not yet fully grasp, that those pictures you shot at a party when you were 16 could resurface at a job interview when you are 25 or end up being used against you in a political campaign when you are 45 because they have persistence online and can be accessed by many unintended audiences? These are some of the questions that contemporary teens face which are different from those confronting previous generations of teens.

Do you think that the leap between the 2010 generation and the 2020 will be as significant as the leap between the 2000 and 2010 generations? Or have the main, structural changes, already happened?

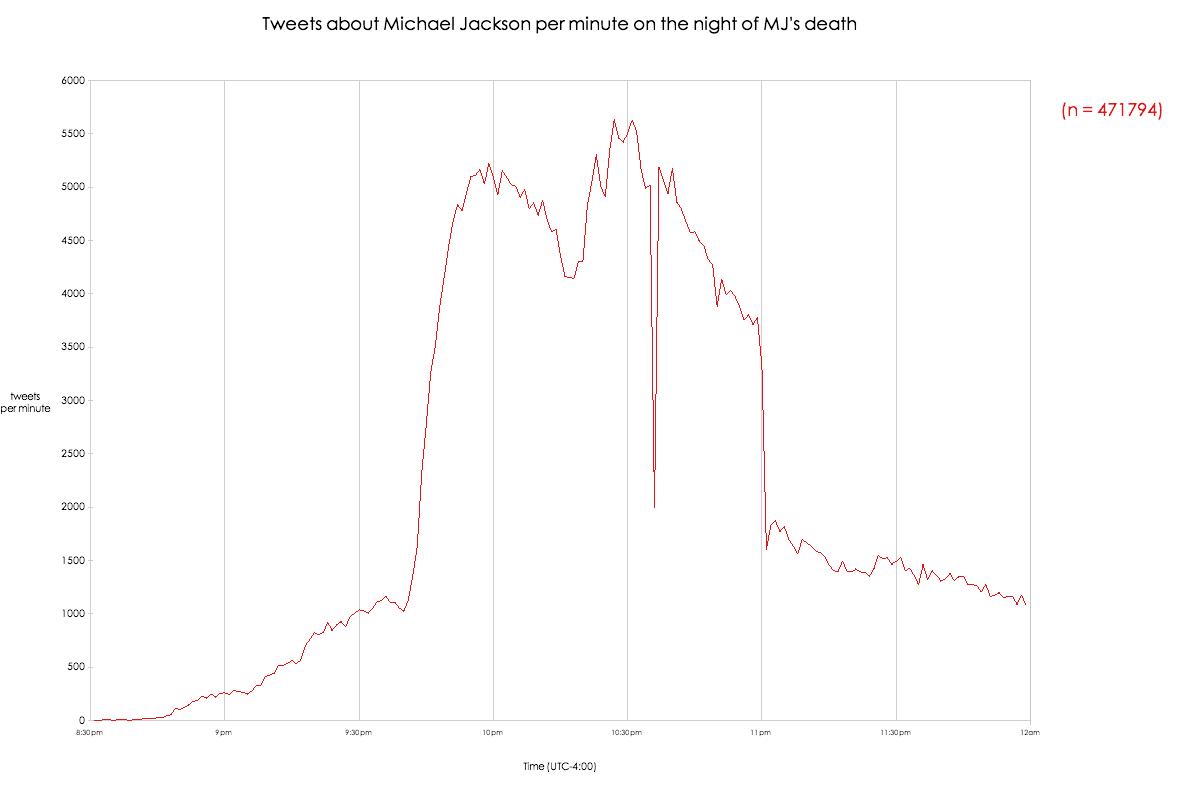

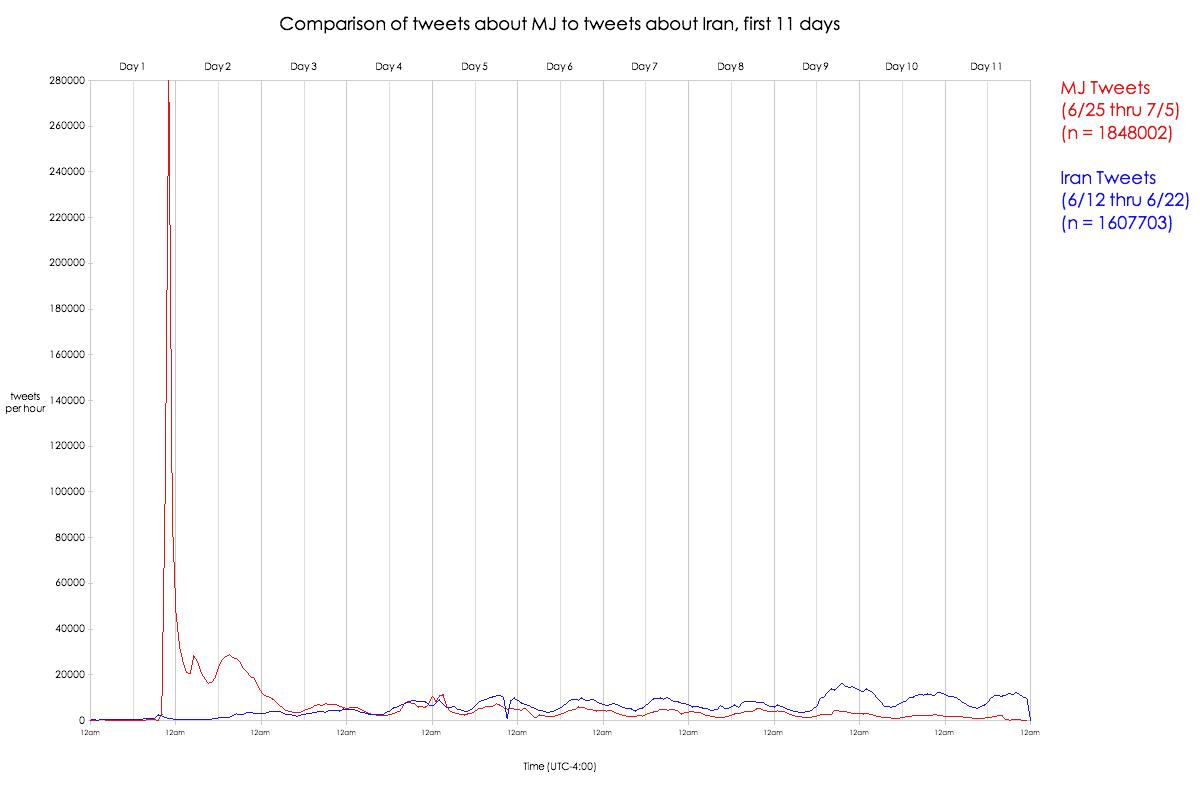

We are in the midst of a profound and prolonged period of media transition which is inspiring changes on every other level -- economic, social, cultural, political, legal... and I don't see the rate of change slowing anytime soon. Youth are often the earliest adapters and adopters of those emerging technologies and cultural practices as they seek out some place they can call their own, some place where their parents and teachers are not going to be nagging at and snooping on them. Young people, thus, embody the change that media is bringing and they are thus likely to be the advanced guard for most cultural practices. (Interestingly, this is not true for Twitter which has spread from the professional classes outward and downward to reach youth rather than the other way around). As this happens, they are going to create differences in style and taste which signal their differences in identity and affiliation. So, yes, I think that youth ten years from now will be significantly different from youth today -- with my above caveat that it will still be the case that the continuities in experience and interests will far out distance the differences.

Which aspect of the DIY/collaborative philosophy, that transformed the youth (and the world), seems more intriguing and relevant for you now?

For the past three decades, I have studied fan cultures as the springboard for grassroots creativity. Fans are people who are inspired by the stories that circulate through the mass media, who take elements of those stories and deploy them as the raw materials for their own creative expression, and who bond together over their shared investments in these rich cultural materials. I don't call this "do-it-yourself" but rather "do-it-ourselves," because of the deeply collaborative nature of these forms of cultural production. They are collaborative both in the sense that they build on existing stories, including those of mass media, within our culture and because they depend on each other to create the infrastructure which supports their creativity. Fan fiction is collaborative from conception -- as fans talk through story ideas as cafe table conversations, as they give each other feedback through Beta-Reading (peer-review) processes, as they read and comment on each other's shared works, and as they build the very platforms through which they circulate their creations. The fan fiction writer exists alongside the cosplayer who creates costumes and embodies characters, the fan musician who creates, records, and circulates songs, the vidder who re-edits and remixes footage, and so forth. All of them form communities which embrace new participants, which generate new forms of creative expressions, which teach each other the skills needed to participate, and who support each other's creations. This kind of participatory culture has existed for more than a hundred years, but the web has made it accessible to a much broader array of participants. Because it can innovate outside the constraints of the market or the art world, it is endless generative and thus a source of ongoing fascination to me.

The transformations that the web caused are already present in almost all the Western world, but parents and teachers are still trying not only to understand it, but to accept it. Why do you think they´re still in denial?

Some parents are in denial; some are in a state of panic. The first sees no change occurring, the second fears the change that is coming. Few are finding the middle ground between the two which allows young people plenty of space to navigate between neglect and constraint. I just heard the story of a young man, who came from a conservative religious family, who was told by his parents that he could not watch Family Guy or other Fox shows on television. The kid watched it on the internet instead without guilt, since his parents hadn't set up any restrictions on what he did on line. As someone who is the parent of a 29 year old son, I can tell you that most of parenting is reactionary. You are uncertain about the right way forward and so you fall back on what your parents did, even if they were dealing with different times and situations. You end up saying everything you thought you would never say to your kids because the script you have in your head bears the early imprint of your parent's philosophy. And you have to make a very conscious effort to change or reverse those impulses. You may change it some of the time, through sheer act of will, but then you will find yourself reverting back on other fronts. Most parents now do not have a script in their heads for thinking about what young people are doing with their iPhones. The young people are encountering situations which seem on the surface totally different from anything they faced growing up. That's why I always stress the continuities first. They may not know what the value is of having lots of friends on Orkut, but they do know that forming friendships is a vital part of adolescent culture. As the next group of parents grows up, they will have a better mental framework for thinking about these issues but unfortunately, their kids still won't believe they have any clue what they are talking about. :-)

During years journalists, teachers and other specialists considered videogames as a media that causes much more damages than benefits. Do you think that that perception changed?

Yes, somewhat. The good news is that the group of people entering the teaching profession over the past five or so years probably grew up playing Super Mario Brothers and so they have a much more normative understanding of what games can be used for. The bad news is that research shows that of ten different professional classes, teachers are the least likely to still be playing games today. Teachers are consumate creatures of the book and if anything, they are becoming more defensive about these new media as they fear that print culture may be displaced by digital. So, you have some teachers who do get the value of games as recreational and teaching tools, that want to see better games developed which they can deploy through their teaching, that may respect and value the kinds of teamwork and leadership skills being fostered on World of Warcraft, who may understand the simulations of history and government offered by Civilization or Sim City, We are seeing libraries embracing gaming as a community building activity for their patrons. And among educational researchers, games for learning constitute a high growth area of research. On the other hand, you see schools locking out most forms of participatory culture, closing out not only games but also Facebook, YouTube, and Wikipedia. You are less likely to see teachers who believe that playing Grand Theft Auto is going to turn their students into school shooters, but you are more likely to see teachers who believe video games are simply distractions from real learning, rather than recognizing how at least some games can be vehicles for the learning process. I will be happy when our government officials stop telling kids to turn off their XBoxes and do their homework, and start telling them to turn on their XBoxes and do their homework, but that's going to be a long time coming.

Survivor, The Matrix and American Idol are some of the franchises you used as example in Convergence Culture. Any other relevant examples appeared recently?

Franchises still dominate our media production. If I were writing the book today, I might have chapters focusing on Lost, Heroes, Glee, Avatar, and District 9, each of which represent a somewhat different way of thinking about the media's relationship to its consumers. Indeed, each of these franchises plays a role in my next book, which I hope to be writing later this summer, on spreadable media. So, let's take Lost. On the one hand, Lost represents one of the biggest hits on contemporary commercial television. When the Lost finale airs later this week, it is going to attract a massive audience. It is event television on a global scale. People will gather in large theaters all over the United States to watch it. They were flood Twitter and the other social networking sites with their responses. On the other hand, Lost represents all of the properties we would have associated with niche television a decade ago. It is a complex and demanding program. It draws a hard core, socially active, culturally generative audience. It challenges the collective knowledge and thinking of large scale social networks of people who pool their knowledge, compare notes, and try to figure out the mysteries of the island. And as they do so, they follow Lost through podcasts, websites, wiki projects, alternate reality games, and countless other platforms. Lost is television outside the box -- television in a transmedia environment. Each of the other examples I cite represent the further move of television into a transmedia and participatory world. With Glee, we might pay attention to it as a vehicle for selling music -- in that sense very much like Rock Band and Guitar Hero -- and we might talk about it as inspiring lots of amateur performances -- check out all the amateur performances of the songs from Glee which spring up on YouTube within hours of the airing of a new episode. With Avatar, I am of course interested in 3D but also in the ways that activists around the world have embraced the identity of the Na'Vi and their struggle against the cloud people as a language through which to talk about their own local struggles to protect their environments and their way of life. With District 9, I am interested in the ways that a small scale movie gains the level of public interest this film did through strategies which rely heavily on the most engaged and socially networked segments of their audience. And the list continues.

Ten years ago, in Brazil and many other countries, kids found it hard to feel attracted by their schools. Now, with their connection with technology and the internet, it´s ten times worse. Do you think that most countries are facing this problem properly?

I teach a class at USC on the New Media Literacies. One of the assignments is to have my graduate students interview a teenage student or a teacher they know. My students come from all over the world and since they tend to interview people in their own families, I see projects on people who live in many different countries. Almost without exception, every young person they interviewed had a more intellectually rich life outside of school than inside. The things they cared about, they things that provoked their curiosity and passions, were often things which had no place in the current configurations of schooling. The ways they learned best often involved tools and platforms which were blocked in the classroom. And they felt like what was turning them on intellectually was largely unknown by the adults in their lives. The teachers also expressed frustration about how much new technology they needed to absorb or about how hard it was to change the presumptions of school administrators that such tools were distractions from the core business of learning. This is bad enough as a global problem if we think about schools shutting down the brains of our most networked young people, but we might feel that they still get extra educational opportunities and cultural experiences outside the school hours. But then consider all of those young people who only get access to these technologies at school, for whom the teacher or librarian may be the only adult they know who has any understanding of the technical, social, cultural, and ethical challenges and opportunities they represent. If we shut these practices out of our schools, we will have denied those young people the support they need to meaningfully engage as citizens, workers, learners, and expressive individuals in a world where these technologies are going to be taken for granted. Young people are not better off being told to learn about technology on the street corner the way my generation learned about sex. Our schools need to develop a coherent, informed, creative approach to technology which incorporates the best tools and practices into their pedagogical approaches.

How do you think that the new generation is absorving so much information? Do you think they absorb less - after all, the information is at reach all the time - or less?

First, I think there is a shift away from an emphasis on learning information towards learning how to find information. The emerging generation tends to offload much of what they know into technological devices which they use to enhance their thinking. Take away my laptop and you chop off a chunk of my brain. This is not necessarily a bad thing because the information is changing at such a rapid pace. Yet, it only works if we don't fill our heads with misinformation, if we develop skills at evaluating information and recognizing what kinds of information we need to solve particular kinds of problems. Second, they are learning to depend on each other for information they may lack. This is what we call collective intelligence -- a world where nobody knows everything, everybody knows something, and what an individual knows can be shared with the group as needed. Young people are learning to recognize the expertise of their friends and others in their networks and learning to work together to solve complex problems which they would not be able to tackle on their own. So, there are two ways of processing the massive amount of information which the web makes available to us -- deploy tools which sort and filter the information or tapping into collaborative communities which appraise the information together from many different perspectives. The later, for example, describes how I use Twitter. I subscribe to the feeds of the smartest people I know in many different fields and trust them to insure that I at least get exposed to the key developments in those fields each day. Young people are tapping this in a more informal way, which is why young people often know a lot about current events without ever seeming to read a newspaper or watch the news. A lot falls through the cracks this way, which is why we need to foster these skills more, but it is still a pretty shrewd approach to dealing with what previous generations have described as information overload.

As schools, many companies that hire young people are not prepared for all the changes that are happening. How does that affect young people? They will try to adapt or look for new kinds of jobs?

Our young people have much more to give the world than they are being allowed to contribute. No question about it. When we read reports of fans developing online reference works for Lost, say, there's often a dismissive response that says they had too much time on their hands. I don't want to undercut the value of this grassroots production of knowledge and culture on its own terms, but I also want to ask - whose fault is that? Such activity emerges in a world which undervalues the creativity and knowledge, the skills and intelligence, of every day people -- undervalues it in school, undervalues it in the work place. As a result, young people create alternative spaces where they can learn and share what they learn with each other. It can be enormously frustrating to watch the company where you work make bad decisions because it is ill-informed about alternative possibilities, even as you sit there, knowing about new ways forward, and not being solicited to contribute, or sitting there going through mind-numbing repetitive activities while you know a high tech way which would be more effective and efficient. Just as schools need to change to embrace new ways of learning, companies need to change to embrace new ways of working. The most forward thinking companies have relatively flat organizations which allow new ideas to emerge bottom up from any corner of their staffs. They reconfigure teams so that everyone has a chance to lead and people can contribute based on their skill and expertise. As we think about who might be best at working in such an organization, it may well be someone who grew up playing massively multiplayers games, swaping roles, trying new identities, tackling new challenges. Hell, don't just hire an individual gamer. Hire an entire squad or guild, since this team of people already knows how to work together to achieve its goals, already knows what each member can contribute, and already trusts each person to carry their own weight. It isn't just that companies need to embrace new technologies; they also need to recognize and value new cultural processes which come out of young people's experience of growing up in a networked society.

Last week Rio received his first TEDx (a version of the original TED) and the main attraction was a 13 years old boy that knows how to program apps for iPhone and iPod Touch. Many scientists are trying to understand the brains of people like that boy, that could be the next Bill Gates or Steve Jobs. Do you think that makes sense, that they´re treated that way? Or in some years there will be thousands of kids like that one everywhere?

Our focus should not be on prodigies. There have always been child prodigies. There will always be child prodigies. That tells us little about the state of our culture. What we need to pay attention to are the remarkable achievements of perfectly normal girls and boys who are doing things that would have been inconceivable for earlier generations. Their ability to tap into social networks, to deploy new tools and technologies, to process complex information, is astonishing, yet often dismissed by their parents and teachers because it doesn't fit within the grids through which we evaluate their educational performance. It may well be the case that what this young man is doing will become much more widespread in another generation's time, especially as the processes for designing aps are better understood and toolkits more user friendly. In any case, I would want to understand not just how the boy's brain works but also the social support system around the child. What kinds of help has he received from parents, teachers, other adults along his path to this level of accomplishment, since no kid gets to this point alone. In general, we need to understand such developments not as singular cognitive accomplishments but as windows into the kinds of learning ecology which is needed to make it possible for every young person to achieve their full potential.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=109ac4a3-ec52-4124-b22b-1e772f3950af)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=185a3a03-6241-46e9-8e94-94f87355ac95)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6fd8f73b-d54f-4ef7-a896-4ffeb2a19c56)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=5a4fe068-df48-4328-9c24-9e2cc10f3fde)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=32c2f2db-1482-4b34-9502-4e2c841ae0b7)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=7b7b43e7-c1a2-4001-bada-efc82508d276)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=ec053f8e-cbb2-4747-bf27-39128120381b)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=9074b37f-9b36-4617-9945-60ace90a179b)