One of the most productive things to come out of the University of Virginia conference was some rapproachment between political economy (which dominates the current media reform movement) and cultural studies (which has been much more closely associated with the participatory culture paradigm). The cliche is that political economy is all structure and no agency and cultural studies is all agency and no structure. We are, as Robert McChesney suggests, at a "critical juncture" because there are structures and constraints which could be locked down, resources that can be lost, and rich potentials which are fragile. In such a time, we need to look at both agency and structure and so we need to end the theoretical conflict in favor of identifying shared goals -- working together when we can, working separately but in parallel where our goals and tactics differ, but wasting little time on squabbles on the borders between fields. I learned more from conference participants about what steps had already been taken within the media reform movement to embrace some of these same principles. What follows might be described as a partial agenda for media reform from the perspective of participatory culture, one which looks at those factors which block the full achievement of my ideals of a more participatory society.

"The Only Thing We Have to Fear is Fear Itself": Right now, much of our public policy is being fueled by fear and anxiety about cultural change. There is a gender dimension to this politics of fear -- we fear our sons (through anxieties about media effects, school shootings, and video game violence) and for our daughters (through anxieties about sexual molestation through social networking sites or sexual exposure through content-sharing sights). Such fears surfaced in response to recent efforts by the Internet Safety Technical Taskforce to shift the terms of the debate about youth's digital access. The group dared to question the "sexual predator" myths which currently shape public policies, only to become the target of aggressive smears by sensationalistic news, cultural warriors, and political leaders, who have found fear-mongering a productive strategy for raising money, capturing eyeballs, and mobilizing voters. As Anne Collier (Netfamilynews) recently suggested, people can not meaningfully participate in these emerging social and cultural structures if they are worried about their physical well being or emotional safety, yet safety concerns should not be deployed to block access and restrict participation. Rather, there is a need for education which stresses ethical responsibility and civic awareness; trained teachers and librarians need to help young people to grasp the potentials and route around the risks of online communication. Before we can make progress on most of the other policy issues here, we need to develop strategies for decreasing the role of ignorance and fear in public debates about new media.

From Digital Divide to Participation Gap: For the past decade, there has been a concerted effort to wire schools and libraries as a means of overcoming the digital divide and insuring that every American child has access to networked computers. This ongoing struggle around technological access has brought about some real changes, but it has also revealed deeply cultural divides. The participation gap refers to these other social, cultural, and educational concerns which block full participation. Ellen Seiter, for example, has explored how inequalities in cultural capital undermine school-based programs for media education. Unequal access to free time outside of school and the workplace make it much harder for some to contribute content or participate in online communities than others. Much as the old "hidden curriculum" determined which young people did better in schools, the new "hidden curriculum" is shaping who feels empowered and entitled to participate.

Remaking Schools: The MacArthur Foundation's Digital Media and Learning Initiative has brought together hundreds of researchers around the country who are seeking to reinvent public institutions (schools, libraries, museums) to reflect this alternative understanding of participatory culture. Mimi Ito, Michael Carter, Peter Lyman, and Barrie Thorne's Digital Youth Initiative has undertaken a large scale ethnographic study of the many different sites (inside and outside schools, inside and outside homes) through which young people connect with the online world and the kinds of informal learning which occurs through their friendship-based and interest-driven networks. Their project maps a "learning ecology" based on participatory culture principles yet many of the most valuable practices -- especially those which involve young people linking through social networks or producing and sharing media -- are blocked by federal and local educational policies. While schools and libraries may represent the best sites for overcoming the participation gap, they are often the most limited in their ability to access some of the key platforms -- from Flickr and YouTube to Ning and Wikipedia-- where these new cultural practices are emerging. As these insights get translated into curriculum and pedagogical practices through schools, we need to avoid narrowing this emphasis onto 21st Century Skills which prepare young people for the workplace rather than the model of expressive citizenship suggested by the MacArthur Foundation's emphasis on New Media Literacies. The reliance on standardized testing is in some cases shutting down the potentials for intervention through education and in other cases restricting our understanding of these new skills to only those which can be tested and measured.

Rethinking Collective Intelligence: As writers like Yochai Benkler, Jane McGongel, Thomas Malone, Axel Bruns, and others have suggested, activities such as writing Wikipedia or solving Alternative Reality Games offer vivid examples of the ways that social networks may pool their resources, share their expertise, and solve problems more complex than any individual could imagine. O'Reilly's "Web 2.0" model, consciously or otherwise, blurs the line between Pierre Levy's notion of "collective intelligence" and James Surowiecki's "Wisdom of Crowds." Levy's model is deliberative, depending on people forming communities to work together towards shared ends, and he sees it as a cornerstone for any future vision of democracy in the digital era; Surowiecki's "Wisdom of Crowds" is aggregative, relying on a model of a market driven by individual consumer choices. Needless to say, the "wisdom of the crowds" model is proving much easier to assimilate into corporate logic since it still relies on the autonomous and isolated consumer rather than a recognition of the collective bargaining potential of networked publics. We need to continue to push for alternative platforms and practices which embrace and explore the potential of collective intelligence so that we better understand what kinds of ethical, pedagogical, and political principles must be in place before we can realize new forms of citizenly engagement.

Promoting Diversity: While expanding who has access to the means of cultural production and distribution has the potential to broaden the range of stories and ideas in circulation, other mechanisms are working to contain the diversity of the online world. As John McMurria has noted, the most visible content of many media-sharing sites tends to come from members of dominant groups, even as minority content continues to circulate within minority communities. Most models for user-moderation of content start from majoritarian principles with no commitment to diversity. Minority participation is intimidated through the hate speech which goes unregulated on the forums surrounding such sites. At the same time, writers like danah boyd and S. Craig Watkins are arguing that social networks act like gated communities, cementing existing social ties rather than broadening them. As people seek out "like minded individuals," social divisions in the real world are being mapped onto cyberspace, reinforcing cultural segregation along class and race lines. John Campbell has explored the ways that online affinity portrals, which claim to serve minority communities, serve the interests of advertisers for data mining and impression management more than they serve any identity politics agenda, further isolating minority participants from being able to speak to a more generalized audience. We might add to this more generalized concerns raised by Trebor Sholz and others about how social networks lock down our membership by making it hard to move our own data or friendship networks from one commercial site to another, suggesting that the segregation of cyberspace may be difficult to overcome.

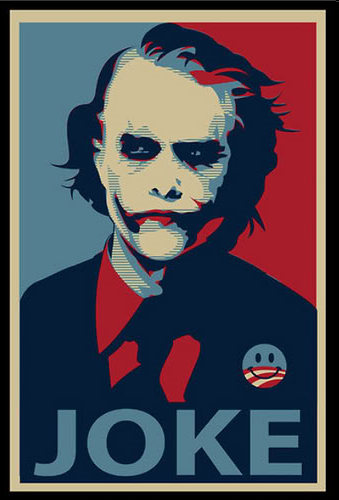

Reasserting Fair Use: As writers like Lawrence Lessig, Siva Vaidhyanathan, Jessica Litman, and others have suggested, struggles over intellectual property may be the most important legal battleground determining the future of participatory culture. While corporations are asserting a "crisis of copyright", seeking to police "digital "piracy," citizen groups are seeking to combat a "crisis of fair use" as the mechanisms of corporate copyright protection erode the ability of citizens to meaningfully quote from their culture. D.J. Spooky's Sound Unbound: Sampling Music and Culture brought together contemporary artists and media makers who saw remix and sample practices as central to their own artistic expression, undercutting the claim that such battles are being fought in the name of author's rights. The Center for Social Media has launched a series of "best practices" documents designed to help remix artists, documentary filmmakers, and media literacy teachers to identify and assert their fair use rights to build on the existing cultural reservoir. Sites like YouTomb are mapping the ways that web 2.0 platforms are responding to these corporate pressures, often by sending out "take down" notices to their contributors, which would stretch well beyond any existing legal understanding of copyright. And now, because these "take downs" are being automatically generated by the company itself, it is increasingly difficult for contributors to overturn them on the basis of fair use arguments. The Organization for Transformative Works has emerged from the fan world as a way of redefining fan practices as falling within the protections of fair use, creating a place where fans can turn when they receive cease and desist orders, while another grassroots organization, Tribute Is Not Theft, has been deploying YouTube itself as a platform to educate fellow contributors about their Fair Use rights and about the value of remix practices.

Critiquing Free Labor: Tziana Terranova was among the first academic critics to call attention to the "free labor" model which remains implicit in O'Reilly's discussion of "Web 2.0." As one joke puts it, "we produce all the content, they make all the money." Talk of an "architecture of participation" masks over the often conflicting interests of grassroots media producers and the commercial platforms they increasingly rely upon for the distribution of their works. The lack of revenue sharing, for example, has been charged with further undercutting the economic base for independent media production, with outsourcing creative labor at the expense of jobs for industry professionals, and commodifying yet not protecting long-standing grassroots practices of cultural production which were historically based on gift economy models. Some are responding with the development of alternative platforms for distribution based on other kinds of political or economic models, whether those which Witness is developing for distributing videos produced by human rights activists or those being developed by the Organization for Transformative Works to protect the rights of fan media makers. Initially, it has been a struggle even to get a recognition that the creation of "user-generated content" should be understood as a form of creative labor as opposed to simply a new form of consumption or an alternative kind of play. As such, the debates over "free labor" represent the most visible part of a larger effort of consumers and citizens to reassert some of their rights in the face of web 2.0 companies, including increased scrutiny over terms of service, growing concerns about issues of privacy and surveilance, and expanded understanding of the consequences of ceding control and ownership of personal data more generally.

Designing Civic Media: As the economic crisis deepens, American newspapers are folding, news media are tightening their budgets and reducing their coverage, and journalists are losing their jobs. While some have argued that we are moving from an age of informed citizens to one based on a more monitorial model, all of these discussions of civic engagement rest on having a source of reliable and meaningful information which can form the basis for our deliberations and collective actions. The idea that professional journalists will be replaced by a volunteer army of "citizen journalists" is profoundly misleading, even if citizens may deploy new technologies to serve other informational needs of their society. Talk about "citizen journalists" is like talk of "horseless carriages," an attempt to understand an emerging system by mapping it onto legacy technologies. American University's Center for Social Media, The Norman Lear Center at the University of Southern California, Harvard's Berkman Center, and MIT's Center for Future Civic Media, among others, are exploring alternative systems for the production and distribution of documentary, alternative resources which support community building and information sharing, and alternative tool sets which allow citizens to transform their society. Huma Yosuf's study of the use of civic media in Pakistan during the recent national emergency suggests that citizens can use these tools to work around censorship, to organize in the face of oppressive regimes, and to alert the outside world about what was happening in their country. Yet, in many cases, these alternative practices still rely on the raw materials provided by professional news coverage and thus we all need to be concerned about the health and independence of the news media.

Thinking Globally: The emergence of new platforms for media sharing and social networking represent alternative models for thinking about the politics of globalization. Throughout the Bush years, when the American super power embraced a unilateral perspective on world affairs, a growing number of American young people were consuming media produced from outside our national borders, often by deploying illegal or semi-legal channels of distribution which connected them directly with fans from other parts of the world. Activists who in the future may be engaged with the politics around poverty, AIDS, environmentalism, energy, or Human Rights, may have first connected around the trade of anime, Bollywood films, telanovelas, or K-Dramas. The practices surrounding the circulation of such materials can be eye-opening as participants discover the protectionist policies and practices which block timely access to international media.

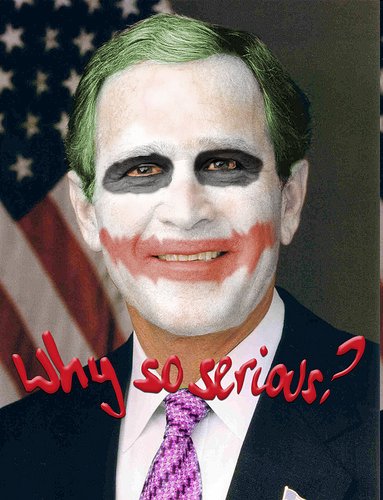

Restructuring Activism: Many of the battles we are describing here are being fought by grassroots organizations framed according to new models of citizenship and activism which emerge from participatory culture. In his recent book, Dream:Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy, Stephen Duncombe makes the case for a new model of social change which is playful and utopian, channels what we know as consumers as well as what we know as citizens, and embraces a more widely accessible language for discussing public policy. We can get a sense of what such a new model of activism might look like by examining movements like the HP Alliance which uses J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter franchise as a shared framework for discussing human rights and social justice issues or the Anonymous movement which deployed imagery from V for Vendetta to mobilize protests against the Church of Scientology. There's much we need to know about what this new kind of political discourse looks like, what its strengths and limits are, and whether it can effect meaningful change. How do we build a bridge between participatory culture and participatory democracy?

In each of these debates, there is a need for critical theory which asks hard questions of emerging cultural practices. There is also a need for critical utopianism which explores the value of emerging models and proposes alternatives to current practices. There is a need for theory which deals abstractly with these shifts in cultural logic and there's a need for interventions which test the value of that theory through practice. There is a need for academic scholarship which trains the next generation and there's a need for conversations which overcomes the isolation between the various groups which are struggling over these issues. There is a need for people who stand outside the system throwing rocks and there's a need for people who can move into the boardrooms and engage in conversation with those in power. It is too easy to draw false divisions between these various causes, too hard to identify the common ground. I am hoping that this conference will allow for meaningful exchanges around these shared concerns.

Sources

The following might be a basic reading list for those of you wanting to understand more about media policy and participatory culture. Most of these names will be familiar to regular readers of this blog, though a few of them have recently been added to my own reading list and will figure in future posts.

Benkler, Yochai (2006). The Wealth of Networks: How Social Production Transforms Markets and Freedom. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bruns, Axel (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life and Beyond: From Production to Produsage. London: Peter Lang.

boyd, dana (2008). Taken Out of Context: American Teen Sociality in Networked Publics. PhD Dissertation. University of California-Berkeley, School of Information.

Campbell, John Edward (2008). Virtually Home: The Commodification of Community in Cyberspace. Dissertation in Communication at University of Pennsylvania.

Center for Social Media (2008). Code of Best Practices in Fair Use For Media Literacy Education.

Center for Social Media (2008). Code of Best Practices in Fair Use For Online Video.

Center for Social Media (2005). Documentary Filmmakers' Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use.

Clark, Jessica and Pat Aufderheide (2009). Public Media 2.0: Dynamic, Engaged Publics. Washington DC: Center for Social Media.

Collier, Anne (2009). "Social Media Literacy: The New Internet Safety," NetFamilyNews.

Duncombe, Stephen (2007). Dream: Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy. New York: New Press.

Hyde, Lewis (2007). The Gift: Creativity and The Artist in the Modern World. New York: Vintage.

James, Carrie with Katie Davis, Andrea Flores, James M. Francis, Lindsey Pettingill, Margaret Rundle and Howard Gardner, "Young People, Ethics, and the New Digital Media."

Jenkins, Henry (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

Jenkins, Henry,Xiaochang Li, and Ana Domb Krauskopf With Joshua Green (2009). "If It Doesn't Spread, It's Dead." Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

Jenkins, Henry with Ravi Purushatma, Katherine Clinton, Margaret Weigel, and Alice Robison,Confronting the Challenges of a Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century.

Lessig, Lawrence (2005). Free Culture: The Nature and Future of Creativity. New York: Penquin.

Levy, Pierre (1999). Collective Intelligence: Mankind's Emerging World in Cyberspace. New York: Basic.

Litman, Jessica (2006). Digital Copyright. New York: Prometheus.

Lyman, Peter, Mizuko Ito, Barrie Thorne, and Michael Carter, Hanging Out, Messing Around, And Geeking Out: Kids Living and Learning With New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press/MacArthur Foundation, 2009.

Malone, Thomas (2004). The Future of Work: How the New Order of Business Will Shape Your Organization, Your Management Style and Your Life. Cambridge: Harvard Business Review.

McGonigal, Jane (2008). "Why I Love Bees: A Case Study in Collective Intelligence Gaming" in Katie Salens (ed.), The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning.Cambridge: MIT Press/MacArthur Foundation.

McMurria, John (2006 ). "The Youtube Community,"

Miller, Paul (2008). Sound Unbound: Sampling Music and Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

O'Reilly, Tim (2005)."What is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software."

Seiter, Ellen (2008). "Practicing at Home: Computers, Pianos, and Cultural Capital" in Tara McPherson (ed.), Digital Youth, Innovation and the Unexpected. Cambridge:MIT Press/MacArthur Foundation.

Sennett, Richard (2009). The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Scholz, Trebor (2006). "Collaboration and Collective Intelligence." Panel organized as part of the Media in Transition conference at MIT.

Sureicki, James (2005). The Wisdom of Crowds. New York: Anchor.

Terranova, Tizianna (2004). Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age. London: Pluto Press.

Vaidhyanathan, Siva. Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How It Threatens Creativity. New York: New York University Press.

Yusuf, Huma (2009). Old and New Media: Converging During the Pakistan Emergency (March 2007-February 2008, Center for Future Civic Media.

Watkins, S. Craig (Forthcoming). The Young and the Digital. Boston: Beacon Press.