Pop Junctions: Reflections on Entertainment, Pop Culture, Activism, Media Literacy, Fandom and More.

Reflections on Entertainment, Pop Culture, Activism, Media Literacy, Fandom and More

We might expect a book called The Dialogues to be fairly text-heavy and we certainly have much conversation here, but some of the more surprising moments come on pages which have little or no dialogue. What role does silence play in your exchanges?

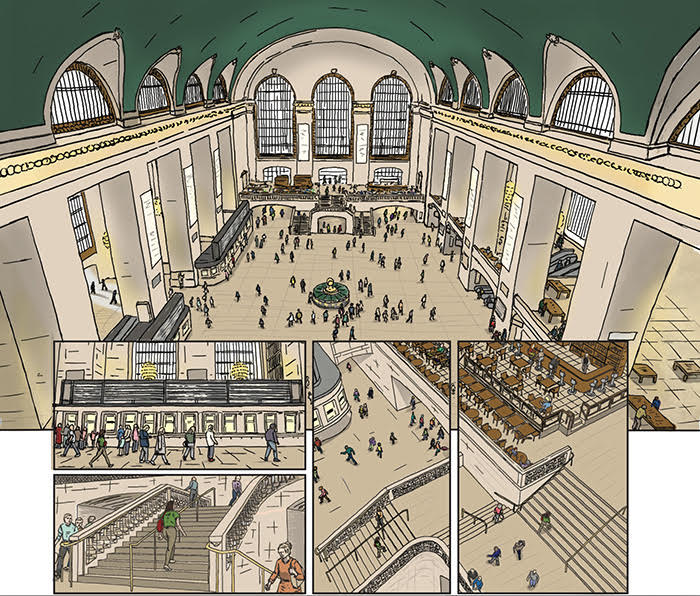

Oh, I love silence in comics! I love the whole business of leaving the reader alone with their thoughts, just providing fragments of a narrative through images that they can embellish in their way. I really wanted this book to breathe, with lots of space for the reader to reflect, or perhaps to prepare for the next set of ideas after finishing the last. I designed every element to facilitate this. This includes pauses in the conversation. Sometimes you need to stop talking and think about the points being made, or just back off from an approach and try another. I wanted to show that aspect of a conversation, for sure. Generally, my publisher (MIT Press) was very generous in allowing me control of every aspect of the design, right down to the cover, even though they were doubtful about one choice. Once a chapter/conversation ends, there’s the notes, and then there’s a double page spread separating chapters that’s a blank page on the left, and then just a simple number (with a window to the next chapter) on the right. A number of editors questioned that blankness, and suggested either skipping it or putting a splash of colour on it. But I resisted. I wanted this as a palette cleanser. A bit of silence before diving into the next chapter. And then in some cases, even after you start the chapter there’s a lot of visuals before you get to the conversation, so you ease in gently, perhaps wondering what concept you’re going to be thinking about next. Actually, since a lot of those opening visuals involve drawing what felt like thousands of windowpanes in skyscrapers, I did find myself cursing my love of architectural detail, telling myself that people are just going to flip through those pages until they find speech bubbles anyway. I briefly considered having a narrator help move the reader through some of it, and maybe act as a connector between stories too, but I did not want to break the silence, and then the narrator risks being seen as me, and there’s the whole voice of authority coming back in. Everyone is so rushed these days but I do hope some people take the time to linger through the silences, and glance at some of the details. I actually went out there into the world and measured the heights of those parking meters! And in some cases completely (after lots of research) constructed the interiors of certain spaces so that I could use them as settings.

I was amused by your opening segment which depicts a conversation between a man and a woman both dressed as superheroes. This seems to be a wink and a nod towards the expectations many have about the kinds of content appropriate for comics. Yet you soon shift towards other comics genres and keep changing ground across the book. In what ways did you play here with audience expectations about comics as a medium?

Yes! You saw that, great! That was exactly the joke. I find myself frustrated, still, that in 2017 people are still mixing up comics with genre. So you see it all through the culture. It is something that affects this very book, since it really belongs with non-fiction science books, but I'm going to have to fight for it to be on those shelves. Instead it's just going to be lumped with comics and graphic novels. It'll be alongside (if if I'm lucky enough to get shelf space at all!) wonderful comics about history or graphic memoirs, etc., and that’s great, but those books should be in the history and memoir sections of the bookstore. But anyway, I could rant about this a lot more. In any case, I thought I would at least amuse myself (if nobody else) by having the book open with everyone in superhero costumes (since that’s what most people are expecting form a comic)… but then you look closer and see that the costumes fit badly, and it becomes clear that it's just regular people in costume at a party. And they are at a museum, and they start talking about science because of the superhero context. I started that story a long time ago in the process, before the ubiquity in people's consciousness of cosplay at conventions and so forth. If I were starting to write it now, I consider just setting it as a conversation in a line at some ComicCon, with costumed people everywhere. Or maybe I wouldn't, since I've learned from bitter experience to try to avoid crowd scenes, along with lots of skyscrapers and their endless rows of windows.

This was not your first experience working with superheroes, since you provided technical advice to Agent Carter’s producers. How did you become a technical advisor for this superhero series and what motivated you to participate in this process?

Oh, yes. I worked on Agent Carter, season two. Actually, I've worked on a lot of other superhero things you might recognise, like Agents of Shield, The upcoming Avengers movies and Thor: Ragnarok which is coming out around now. I think I started getting involved in Science advising for movies and TV well over a decade ago because I’d talk about science and film on my blog, and word got around. Also, I got a reputation as a good explainer from my work as a guest expert on various TV documentaries like PBS’s Nova, The History Channel’s The Universe and so forth. People from the industry started getting in touch. Motivation? I really think that it would be a massive mistake to not use the most powerful and pervasive storytelling tools ever invented - TV/Film - in getting people interested in, or at least familiar with, science and scientist characters. And it shouldn’t just be in documentary. Science is (or should be) part of our general culture, so you should see it everywhere. But anyway, the connection to Marvel in particular really began in earnest because a few years ago the Science and Entertainment Exchange (a nonprofit set up by the National Academy of Sciences to help connect scientists to entertainment people) started to suggest my name to some of Marvel’s producers as someone who can help with big physics stuff like space, time, energy, and so forth. Just what gets played with a lot in the Marvel Universe. The collaboration with the Agent Carter people was particularly successful because they called me in very early, before they wrote much. This is unfortunately still unusual - science advisors are wrongly mostly thought of as fact-checkers to be brought in near the end. I was able to help give them a lot of physics ideas (or fanciful ideas inspired by real physics) underpinning for a lot of the universe they were trying to create, and from that comes not just good visuals and buzzwords, but entire story ideas, character ideas, and so forth, that have the science embedded in them. It was a true collaboration that made that season really strong, in my opinion, because you might recall that her agency was the Strategic Science Initiative, so it made sense that the science needed to be up front.

Clifford V. Johnson is a professor in the Physics and Astronomy Department at the University of Southern California. Here's how he describes his research on his home page: "My research (as a member of the Theory Group) focuses on the development of theoretical tools for the description of the basic fabric of Nature. The tools and ideas often have applications in other areas of physics (and mathematics) too - unexpected connections are part of the fun of research! Ultimately I (and the international community of which I am a part) am trying to understand and describe the origin, past, present and future of the Universe. This involves trying to describe its fundamental constituents (and their interactions), as well as the Universe as a dynamical object in its own right. I mainly work on (super)string theory, gravity, gauge theory and M-theory right now, which lead me to think about things like space-time, quantum mechanics, black holes, the big bang, extra dimensions, quarks, gluons, and so forth. See the research page for more, or look on my blog under the "research" category (here). I spend a lot of time talking about science with members of the public in various venues, from public talks and appearances, various intersections with the arts and media (you might catch me on TV and web shows like The Universe, Big History, or Fail Lab), to just chatting with someone on the subway. I love helping artists, filmmakers, writers, and other shapers of our culture include science in their work in some way. Check out my blog for more about those things, and occasional upcoming events. Get in touch if you are interested in having me appear at an event, or if I can help you with the science in your artistic endeavour."

In your Preface, “Space and time and the relationships between things are at the heart of how comics work: Images (sometimes contained in panels, but not necessarily) arranged in sequence encourage the reader to infer a narrative that involves the sense of time passing, of movement, and so forth. In this sense, fundamentally, comics are physics! Put this way, upon reflection it is stunning that this graphic form has not been used more to talk about physics, and to communicate what’s going on in the fascinating world of physics research.” What are some of the ways you are taping this insight in your visual storytelling across the book?

I use it in some fairly obvious ways in some places, like just having characters moving from frame to frame while actually discussing the whole business of movement. In other cases, I get to do much more subtle things with the form. For example, at one point in a conversation two people are discussing ideas from contemporary research about what might happen to space and time inside a black hole. Without going into detail with me just say that space and time can get rather jumbled up inside – maybe even lose their meaning entirely. So one of the ways I show this is by messing with the order in which you conventionally read the comic frames as you are watching the discussion delve into the black hole. I'm deliberately playing there, deliberately inviting confusion in the interior of the black hole in a way intrinsic to the comic form itself.

In other places I have characters talk about the breakdown of space and time entirely, as might happen at the birth of the universe. There, as they talk about this, I completely dissolve the panels containing the characters and the backgrounds. Frankly, I wish that I had realised this connection between subject and form earlier in writing the book. I would have played with it a lot more than I actually do in this book. I almost want to immediately start work on a second volume of dialogues and cast many more contemporary ideas from physics in this form. If I don't do it, I hope others may try.

One of the real strengths of this work is your focus on particularized locations for the exchanges. Many dialogic texts in the past have been abstracted from any specific physical space, but your drawings are rich in architectural and geographic information. Why? What do these locations, such as Los Angeles’ Angels Flight, contribute to our experience of your work?

Thank you for noticing this! Yes. This is all about being able to show - because I chose this graphic form - that science takes place out there in the world. Everywhere there are people present, science, and conversations about science can take place. It's not just with the experts and it's not just to be left in labs and research centres. From pragmatic perspective, I also have the feeling that readers can get drawn into the book by wondering who and where these people are. I hope they might have fun recognising details of places that may be familiar. The richness you so kindly pointed out is also my weakness by the way. I obsess over details in my drawing. Is one of the reasons why it took me seven years to finish this thing. One of the other reasons is that I was teaching myself more or less from scratch how to draw at the required standard, and how to draw for this medium. It will take a lot more time than I had to also learn the kind of distillation and economy that a true master has. Perhaps I will one day.

Larry Gonick's Cartoon History of the Universe has been widely cited as an example of what it might mean to do science through comics. You adopt a very different approach. Can you say more about the pedagogical choices you made in how to present this material?

I have a confession to make. I've never read that book, although I know of its existence, and of course I have a lot of respect for it. I’ve glanced at some pages from it online and so I know enough about it to put in that class of wonderful books out there about science which are essentially illustrated lectures. I did not want to write an illustrated lecture about physics. Obviously, by being a physics professor writing/drawing about physics, I am still trying to illustrate physics ideas, but I want to get away from the tone (which is not to everyone’s taste) of an expert coming out of the ivory tower and giving the public the benefit of their wisdom. I felt that having the reader eavesdrop on dialogues about science gets the ideas across any different way. And that’s even if some of the people in the dialogues are scientist themselves, as is the case. They're not talking directly at you, and I think that makes a difference. I don't know why. That's probably for my colleagues in the psychology department to tell you.

Often, documentary or instructional comics -- Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics comes to mind -- are monologues in which the author represents themselves on the page lecturing us, albeit in a playful way, about the content. Why did you chose to communicate more through character interactions with accompanying notes?

McCloud’s book is wonderful. I spoken a bit about the choice to avoid lecturing and use character interactions already, but let me say a bit more about the notes. The great thing about conversations is that they are imperfect. I know that sounds a bit odd, but I like that imperfection. In representing conversations on the page then, I get to visit lots of topics, because conversations seldom stay exactly on track. And that ends up allowing me to show the connectedness of science ideas. You can go off in one direction or another. Inevitably there for that means that, unlike a carefully prepared lecture, a conversation won't stay on topic and is less likely to go very deeply into one particular topic. Instead there are notes at the end of each chapter where I list books for further reading on some of the topics that popped up on the conversation. So the dialogues end up being an invitation to, or maybe a tasting menu of, various ideas. And then the reader can dive in more deeply by getting some of the many wonderful books that other writers and scientists have written.

Nick Sousanis, creator of Unflattening, has suggested that thinking through comics about his subject matter fundamentally changed his understanding of his topic. Is the same true for you? What did you learn doing physics through comics?

That book is fascinating, by the way. I finally got to reading it this Fall, and I can see that we’d have a lot of ideas to discuss if we met. I hope to meet Nick one day. (I feel bad that I did not cite his work in my book, but it appeared too late, and in any case my notes are mostly pointers to physics texts. I stumbled on it in a bookstore when I was just at the end of finishing the writing and layout of the dialogues, and about to embark on final art. I had to stay away from it, like I did all books at that time so that I could just focus on the coming year of finding time to frantically complete over 200 hundred pages of final art.)

But to your question. I would love to give some spicy story in answer to this question where at the end I point to some scientific paper I published that owes its insights to my investigations of comics. Maybe I will one day. But I cannot right now because it did not happen. Nevertheless, I am quite sure that my research is helped, overall, by my work on this book. Many scientists will tell you that the process of finding good ways to explain even the most basic concepts feeds positively into their research. It encourages clarity of thought. Also, sometimes, tackling a research problem is a dialogue with yourself or with your collaborators. You are reviewing what you've already done, sometimes explaining it back to yourself to glimpse a pattern or a theme. So, trying to explain concepts about relativity or the nature of time to non-experts (as I do in the book) can be useful. Also trying to explain a character’s principled position on some controversial scientific issue, as I do in the book, helps me clarify my own position. I hope that goes some way to answering your question.

Clifford V. Johnson is the first theoretical physicist who I have ever interviewed for my blog. Given the sharp divide that our society constructs between the sciences and the humanities, he may well be the last, but he would be the first to see this gap as tragic, a consequence of the current configuration of disciplines. Johnson, as I have discovered, is deeply committed to helping us recognize the role that science plays in everyday life, a project he pursues actively through his involvement as one of the leaders of the Los Angeles Institute for the Humanities (of which I am also a member), as a consultant on various film and television projects, and now, as the author of a graphic novel, The Dialogues, which is being released this week. We were both on a panel about contemporary graphic storytelling Tara McPherson organized for the USC Sydney Harmon Institute for Polymathic Study and we've continued to bat around ideas about the pedagogical potential of comics ever since.

Here's what I wrote when I was asked to provide a blurb for his new book:

"Two superheroes walk into a natural history museum -- what happens after that will have you thinking and talking for a long time to come. Clifford V. Johnson's The Dialogues joins a select few examples of recent texts, such as Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics, Larry Gonick's Cartoon History of the Universe, Nick Sousanis's Unflattening, Bryan Talbot's Alice in Sunderland, or Joe Sacco's Palestine, which use the affordances of graphic storytelling as pedagogical tools for changing the ways we think about the world around us. Johnson displays a solid grasp of the craft of comics, demonstrating how this medium can be used to represent different understandings of the relationship between time and space, questions central to his native field of physics. He takes advantage of the observational qualities of contemporary graphic novels to explore the place of scientific thinking in our everyday lives."

To my many readers who care about sequential art, this is a book which should be added to your collection -- Johnson makes good comics, smart comics, beautiful comics, and comics which are doing important work, all at the same time. What more do you want!

In the interviews that follows, we explore more fully what motivated this particular comics and how approaching comics as a theoretical physicist has helped him to discover some interesting formal aspects of this medium.

The Dialogues seeks to call attention to everyday conversations about science. Why? What are the stakes for you as a scientist in calling attention to the ways everyday people think about and talk about science?

It goes back a long time, actually. Many people have liked the way I explain scientific concepts to non-experts, and several kept asking me when I was going to write that non-expert level book that people who do a lot of public science explaining usually end up writing. I was stumped for a good answer. I did not feel that the world urgently needed another of those books…not from me anyway. There’s nothing wrong with those books, they are wonderful resources - it just did not feel urgent, and so I carried on with my other work, doing research, and connecting to the public through various other media. Then 18 years ago (!) I had an idea. What was missing from the literature are science books that focus on the reader being able to see themselves as part of the conversation. As part of the joyful, delightful dance that science can be. So the core idea was to make the entire book a series of conversations. Conversations of a type that any reader may have had, or can be a part of - any time they choose. This takes away some of the tone of the expert telling you what you’re supposed to think, and emphasises participation more. The engagement with science should not be left to the experts - its open to all kinds of people.

What do you want your readers to learn about science over the course of these exchanges? I am struck by the ways you seek to demystify aspects of the scientific process, including the role of theory, equations, and experimentation.

That participatory aspect is core, for sure. Conversations about science by random people out there in the world really do happen - I hear them a lot on the subway, or in cafes, and so I wanted to highlight those and celebrate them. So the book becomes a bit of an invitation to everyone to join in. But then I can show so many other things that typically just get left out of books about science: The ordinariness of the settings in which such conversations can take place, the variety of types of people involved, and indeed the main tools, like equations and technical diagrams, that editors usually tell you to leave out for fear of scaring away the audience. I also get to emphasise (sometimes in microcosm) the dialogue between theoretical work and the experimental work needed to connect it with reality. In one story, two kids theorize about a cooking process and devise an experiment to test their ideas. The experiment is designed well enough to sharply distinguish between two perfectly good theories. This might not seem to be connected to fancy ideas about multiverses and quantum entanglement and other buzz-words people come to contemporary science books for… but that process is core to science.

Why did comics emerge as the best way to share these conversations with your readers? What has been your relationship with comics as a medium?

I said earlier that I had the idea to do dialogues about 18 years ago, but the idea for it to be a comic came years later. There was a visual component in the original idea, yes, but it was mostly to show at the end of each story a bit of what might have got scribbled during the conversation. As though you’d eavesdropped in a cafe, they’d left, and you picked up a scrap of paper they’d written on. Well, years went by and I’d occasionally take the idea off the shelf, tinker with it, and then put it back. But I still did not start on the book. Then around 2006 or so I realised that every time I tinkered the visual component grew. I wanted to show more of the things they’d scribbled… Maybe the order in which the scribbling happened. Then I wanted to show who was having the conversations. Maybe that would engage the reader - we’re social animals, so we tend to be pulled into things that way. Then I thought it would be nice to show that these are happening in everyday circumstances. Cafés, sure, but also trains, buses, museums, on the street, in the home. And then it hit me - the visuals had entirely eaten the prose aspect of the book. What I was working on was a non-fiction graphic novel about science. I realised that there was really nothing out there like it, and then I just had to make it and get it out there into the world. It marked a return to the medium for me. I’d read superhero comics a lot as a kid, and into my early college years, and I was always interested in the art, but not at the level I would become later, for this project. In the early 90s I’d almost fully put them aside for various reasons. I’d dip in from time to time, but did not really become a regular reader again. But around the time the book ideas properly crystallized into a graphic book, I returned to reading the form, discovering that a lot of wonderful expansions into storytelling in a wide range of subjects had happened, and I began to consume many examples. By 2010 I took a sabbatical semester and devoted it to (secretly) studying the form in earnest to learn if I could do it, teaching myself art and other production techniques and so forth from books and lots of trial and error.

Clifford V. Johnson is a professor in the Physics and Astronomy Department at the University of Southern California. Here's how he describes his research on his home page: "My research (as a member of the Theory Group) focuses on the development of theoretical tools for the description of the basic fabric of Nature. The tools and ideas often have applications in other areas of physics (and mathematics) too - unexpected connections are part of the fun of research! Ultimately I (and the international community of which I am a part) am trying to understand and describe the origin, past, present and future of the Universe. This involves trying to describe its fundamental constituents (and their interactions), as well as the Universe as a dynamical object in its own right. I mainly work on (super)string theory, gravity, gauge theory and M-theory right now, which lead me to think about things like space-time, quantum mechanics, black holes, the big bang, extra dimensions, quarks, gluons, and so forth. See the research page for more, or look on my blog under the "research" category (here). I spend a lot of time talking about science with members of the public in various venues, from public talks and appearances, various intersections with the arts and media (you might catch me on TV and web shows like The Universe, Big History, or Fail Lab), to just chatting with someone on the subway. I love helping artists, filmmakers, writers, and other shapers of our culture include science in their work in some way. Check out my blog for more about those things, and occasional upcoming events. Get in touch if you are interested in having me appear at an event, or if I can help you with the science in your artistic endeavour."

How might we think about the social mandate to share in today’s culture in relation to ongoing concerns about the loss of or disrespect for notions of privacy? What relationship do you see between sharing and privacy?

Online sharing would certainly seem to present quite a challenge to privacy: the more we share, the more Facebook et al. know about us. So on the face of it, sharing and privacy stand in opposition to one another. However, there are interesting parallels between them which lead me to see them not necessarily as subsisting in a zero-sum game but rather as giving different expression to a kind of self that took shape during the 20th century.

If I may oversimplify somewhat, the modern right to privacy, as formulated by Warren and Brandeis at the end of the 19th century, emerged in response to modern technologies of representation and reproduction, specifically, the use of photographs in newspapers. The right to privacy has as its object the discrete individual. On one account, privacy is necessary so that the individual may make authentic decisions (for whom to vote, or what to purchase).

Paradoxically, the contemporary injunction to share (as a type of communication) also addresses the discrete individual who expresses her authentic individuality by making it public. In their work on reality TV, Andrejevic and others have shown how self-exposure and its subsequent scrutiny are taken as a guarantor of truth, and I see sharing on social media as an extension of this. Of course, I’m aware that many social media users feel that others are not being authentic in their self-representation, but the rhetoric of sharing on these platforms, and especially Facebook, is all about connecting with others and being your most authentic self. (It has been interesting in this regard to follow Mark Zuckerberg’s comments about apps for anonymous communication, which also claim to offer users the opportunity to be their most authentic self.) Moreover, there are sanctions against not sharing. For instance, refusal to use Facebook can be perceived as deviant; and if we think about interpersonal relationships outside of social media, it seem obvious to me that you will not be able to sustain a romantic relationship without talking about your emotions.

Perhaps the term that points to failure in managing these seemingly competing demands – to share and for privacy – is “oversharing”. This is when we are given too much information, when the boundary between the public and the private – which is always shifting and negotiable – leaves too much in the public sphere. When we accuse someone of oversharing, we are not only saying that we did not want to know that, but that they should not have wanted to tell us in the first place, that they should have had a better sense of their own privacy.

Which term has more moral and emotional weight in our culture -- sharing or piracy?

I haven’t studied the metaphor of piracy per se, though it clearly is a meaningful cultural resource for those more deeply involved in the community (that is, it may not be a term that resonates with everyone downloading the Game of Thrones finale, but it is important to the people who contribute to the file sharing forums I analyzed). The metaphor of piracy is, I think, seen as more subversive among the file-sharers I studied. It’s more edgy than sharing, though one does come across “sharing is caring” slogans and images in members-only file-sharing sites too.

In terms of our broader culture, I think I’ve nailed my colors to the mast pretty strongly here: after all, the book is called The Age of Sharing. I think that the term, sharing, is an extremely powerful term today, both morally and emotionally. Part of the evidence for this is actually provided by people who strenuously oppose its application to practices that they say are “not really sharing”. Sharing, for them, needs to be protected from appropriation by commercial entities (among others).

Your conclusion stresses the unfulfilled promises of the concept of “sharing” in contemporary culture, which is often used to mystify far more traditional kinds of economic relationships. But we could turn this around and say the persistence of the concept of “sharing” across the various contexts you discuss suggests an ongoing desire, amid large chunks of the western world, for an alternative set of economic and social arrangements that does not look like capitalism. Can we deconstruct the abuse of the concept of sharing while keeping alive the radical potential of these shared social values? As you ask, “if the promise is extinguished, what are we to do?” (155)

What are we to do? I wish I had an answer.

Were I asked to present a blueprint for the Good Society, I have no doubt that it would include sharing: my good citizens would share resources; relationships would be built on openness and honesty. But in fact this blueprint says a great deal about my cultural circumstances; perhaps more than the desirability or attainability of this Good Society. There certainly is an ongoing desire in large chunks of the western world for an alternative to capitalism – an important wing of the so-called sharing economy is trying to present such an alternative – but our ability to imagine this alternative is defined, or at least shaped, by our present-day culture. I certainly think this is the case when we imagine a past in which people shared and drew inspiration from that past, and I think this is what Benjamin was intimating with his notion of an ur-past, a mythological past of harmony. With the help of anthropologists, in the book I argue that our conceptualizations of hunter-gatherer societies as grounded in sharing are anachronistic and misplaced. We imagine a better past (and future) from our place in the present. How could we do otherwise?

It is from this perspective that I refrain from talking about the abuse of the concept of sharing. Culturally speaking, the concept and its “abuse” have common roots. I suppose this is another way of saying that we cannot get outside the system. This isn’t to say we should critique the system (whatever we perceive that as being), but it is to suggest that arguing about whether this or that is “really” sharing isn’t going to get us very far. If there is a problem with certain parts of the “sharing economy” it isn’t that it is called “sharing”, it is that people’s labor is being exploited.

Nicholas John is a Lecturer at the Department of Communication and Journalism, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research interests include technology and society, the internet, social media, sharing, and unfriending. He is the author of the award-winning book, The Age of Sharing. This book offers an innovative approach to sharing in social media, specifically by linking it to sharing in other social spheres, namely, consumption and intimate interpersonal relations. The book won the Best Book award from the Israel Communication Association, and the Nancy Baym Book Award from the Association of Internet Researchers. Nicholas is also interested in disconnectivity, which he sees as a neglected aspect of digital culture. In particular, he is fascinated by Facebook unfriending, particularly when it is politically motivated. He sees unfriending as a new political and social gesture that we know very little about. His teaching looks at the complex interrelations between technology and society.

To what degree was sharing part of the early hacker and counter-culture ethos which shaped our understanding of cyberspace? To what degree might it have emerged from the science and technology culture of research institutions such as MIT and Caltech which also placed a value on the open exchange of information?

It was absolutely part of the early hacker culture, and indeed of early computing culture. However, I find claims that the internet, or cyberspace, has always been about sharing to suffer from the same anachronism as claims that prehistorical hunter-gatherer societies were about sharing. This is because I’m interested in the use of the word, and the word did not come to represent the internet until the mid-2000s. The key text on the counter-culture’s role in the cultural signification of the internet is Fred Turner’s From Counterculture to Cyberculture. What I find worthy of note is that nowhere in the book does he talk about sharing as value of the internet; nor, incidentally, does Howard Rheingold in The Virtual Community. Today we understand cyberspace in terms of sharing, but we did not thus understand it even as recently as the early 2000s.

The second part of this question is, in my reading, an empirical question, which one would answer by looking through the archives of those institutions. Did they talk about sharing? Is that how the open exchange of information was discussed? I don’t know, but it could be interesting to look into that.

Why has sharing become the prefered language for talking about what we do when we participate on social media? What other potential frames might we consider for thinking about these activities?

There are three main reasons for this. The first sees “sharing” as emerging organically from the field of computing, where it has long been a term in use (as I mentioned earlier in relation to time sharing).

The second is that the term, sharing, covers so much. It refers to both the distributive and communicative aspects of sharing, and it incorporates a wide range of other terms that might be used in describing social media activities, such as “express yourself”, “post”, “connect”, “socialize”.

The third reason is that “sharing” has such positive connotations, encapsulated in the phrase, “sharing is caring”.

Taken together, these reasons point to a term that is both an organic part of the world of computing, and that has been leveraged by social network sites’ PR people. If you look at the front pages of the major SNSs over the first decade of the century (something I have done so that you don’t have to), you can see the word “sharing” becoming more widespread over that time, but particularly between 2005-2007. Facebook played an important role in this. They adopted the concept of “sharing” in 2006, which seems to have pushed other companies to present themselves in that terminology too.

This suggests that the term, sharing, came relatively late to digital culture, which begs the question, what other frames were used prior to that point?

One significant frame was that of “gifting”, but I see “gifting” and “sharing” as quite different. First, I would note that “gifting” and “sharing” are different in that the former was a theoretical concept used by scholars to describe activities they were witnessing (making music files available to others on Napster; creating websites), while sharing became the term used by social network sites to describe participation on them. So actually “gifting” wasn’t the term used by participants, but rather by observers.

Be that as it may, gifting refers to the distribution of goods, even if they are immaterial goods. Sharing refers both to the distribution of goods and to a form of interpersonal communication. Because sharing as a type of communication implies honestly, openness, authenticity, and more, it is far wider than the notion of “gifting”. To say that someone is sharing is to suggest that they are giving something of themselves. More than gifting does, it implies caring, perhaps even altruism.

The phrase, “the sharing economy,” has been applied to everything from Uber to Wikipedia. How can we make meaningful distinctions between the different forms of “sharing” involved here and the ways what gets shared does or does not become part of a larger “economy”?

There have been plenty of attempts to make this distinction. Lessig talks about me-regarding and thee-regarding economies, and about thin and thick sharing economies; Belk talks about sharing in and sharing out, and also about sharing versus pseudo-sharing; in a slightly different context Haythornwaite talks about crowds and communities. There have also been other efforts to shift the terminology, perhaps most notably Hillary Clinton’s promotion of the term “gig economy”.

I think, though, that the horse has bolted, and that the term “sharing economy” is here to stay. More than that, I think that the very word “sharing” may get another layer added to it. When attending a sharing economy meet up in Manhattan, one of the panelists spoke of different models – sharing for free, and sharing for money. None of those in attendance objected to this (perhaps they were being polite), which raises the possibility that “sharing” will also come to mean something like “using an app to rent out possessions”. If this happens, does that mean that there will be no more sharing (the “good” kind) in the world? I don’t think so, but I’ll save my thoughts on this for the final question.

You discuss sharing in the context of a therapeutic discourse, which links it to notions of individual wellness and social health. Yet, could we also see the concept at work in political movements, like the feminist consciousness raising sessions of the 1960s or the giving of testimony in a range of social movements across the 20th century? This political notion of sharing involved recognizing commonalities in social experiences as the basis for framing larger critiques of the current order.

I don’t feel particularly qualified to comment on the feminist movement of the 1960s or the giving of testimony in other contexts. What I can say is that in these contexts it seems that the authentic individual experience is given voice. By hearing others’ voices, one may feel empowered – it’s not just me! – and by giving voice one may also feel empowered – this is who I truly am! These instances, then, seem to belong as much to the therapeutic discourse, which extends far beyond the therapist’s clinic.

I would add here that my investigations into the origins of the therapeutic sense of “sharing” lead back to an evangelical group that was active in the US in the 1920s and ‘30s. Called the Oxford Group (no relation to the university), its key practice was as follows: members would sit together in someone’s parlor or drawing room and take it in turns to publically confess their sins. This practice was called “sharing”. Two alcoholic members of the Oxford Group adapted this practice to allow other alcoholics to talk about their experiences in a non-judgmental setting. This became Alcoholics Anonymous (where participants are famously thanked for sharing), which, to the best of my knowledge, is where the ideas of sharing adopted by countless other groups and organizations – some of them more psychologically oriented, and some of them more political – were institutionalized.

Nicholas John is a Lecturer at the Department of Communication and Journalism, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research interests include technology and society, the internet, social media, sharing, and unfriending. He is the author of the award-winning book, The Age of Sharing. This book offers an innovative approach to sharing in social media, specifically by linking it to sharing in other social spheres, namely, consumption and intimate interpersonal relations. The book won the Best Book award from the Israel Communication Association, and the Nancy Baym Book Award from the Association of Internet Researchers. Nicholas is also interested in disconnectivity, which he sees as a neglected aspect of digital culture. In particular, he is fascinated by Facebook unfriending, particularly when it is politically motivated. He sees unfriending as a new political and social gesture that we know very little about. His teaching looks at the complex interrelations between technology and society.

Today, I want to share with my readers an interview with the author of a smart new book, The Age of Sharing -- well, I wanted to share it with you, but Nicholas John does such a great job in this book of drilling into and complicating my understanding of the very concept of sharing that I am now not certain that's what I want to do after all. I will post it. You may recirculate it. But should we call this sharing?

The central project here is to understand how the meaning of sharing has shifted over time, the ways the term has been dematerialized (no longer about material relations) and made to stand in for all kinds of social interactions, the ways the term has become central to our understanding of the digital age and yet it continues to mean somewhat different things to producers and consumers in an era of social media. I learned a lot in this book about the history of sharing as a concept and a set of practices, and it sets us on a path to a more nuanced deployment of the term as we talk about what it is we are doing with each other in an era of spreadable media content.

I hope this interview captures your interest so that you will pick up a copy of the book for yourself.

You write, “When we -- English-speakers in western societies -- hear talk about sharing today, we understand the concept differently from both our grandparents and their grandparents.” (20) How so? Can you characterize what the term, sharing, meant in each of these periods?

Obviously the answer may depend somewhat on how old the reader is, but what I’m getting at here is that new layers of meaning have been added to the word, sharing, giving it its current set of connotations and meanings. (Of course, today’s constellation of meanings is just as unstable as any set of meanings in the past.) Today, obviously, sharing refers to digital participation. I have called sharing the constitutive activity of social media to highlight how it has become the key word for describing our online participation. It covers the whole range of digital activities: updating statuses, uploading videos, sending messages, posting pictures – all these are called sharing. More than this, though, a crucial aspect of the meaning of sharing today is its sense of fairness and caring, which are tightly linked to sharing as a specific type of talk about our emotions. This association of sharing with rainbow colors and intimacy is new – when my 92-year-old grandmother was a young woman, this sense of sharing would not have been accessible to her. In the 1940s and ‘50s, she would not have come across the idea that “sharing is caring”. Needless to say, none of the digital implications of sharing would have been available to her either.

She would, though, have understood sharing as a kind of talk about emotions. This had been emerging particularly since the 1930s as part of the secularization of romantic relations, especially those between husband and wife.

My grandmother’s grandmother, living around the turn of the previous century, would not have understood sharing to be a type of talk at all. The metaphor of sharing one’s troubles would have been accessible, and obviously one shared one’s troubles by talking about them, but the talk itself was not called sharing. We can understand this best by going further back in time, to the 16th century, when sharing meant dividing – this is the pre-metaphorical sense of sharing. Consider the similarity between the words “sharing” and “shearing”: this is no coincidence; “to share” used to mean (and sometimes still means) “to divide”. In fact, the old English word from which “sharing” evolved, namely, scearu, had two meanings. One referred to the groin, that part of the body where the trunk of the body divides into two legs; the other referred to a monk’s tonsure, where his hair had been sheared off. Sharing one’s troubles, then, meant dividing them in two, and giving a portion to your collocutor, thereby reducing your burden. The metaphor here is still physical. It wasn’t until the 1900s that the word sharing started being used to refer to the talk itself, taking another step away from the rather material, pre-metaphorical sense of the word.

Looking back over how the concept of sharing has changed over the last 100 years or so, I would say that it has added layers of meaning that take it further away from its material sense of sharing as dividing. This has included the institutionalization of sharing as a type of talk, and also the notion of sharing as morally desirable, exemplified, for instance, in the way parents (especially American parents) teach their children to share nicely.

As I read you, part of what has taken place has been the dematerialization of the concept of sharing -- from an early emphasis on cutting into parts or cutting off -- to the contemporary sense where the exchange of information also often involves the exchange of feelings and may play an active role in shaping the social ties between parties. How do you explain these shifts over time?

Yes, the concept of sharing has been dematerialized. This is a useful way of thinking about it. But we should remember that the development of many metaphors is about dematerialization, or perhaps even more specifically, decorporealization, as so many metaphors – including sharing – have their origins in the body.

I think that there are two broad paths to the current meanings of sharing. One is related to shifting conceptualizations of the self throughout the 20th century. Perhaps it might be more accurate to say that it is related to the emergence of the specific idea of the self that we have today. This is a self with a coherent core, that is accessible to us through talk, and conveyable to others through talk. This is the Freudian, therapeutic self. The emergence of this sense of self is concurrent with secularization and urbanization, and what T.J. Jackson Lears calls a thinning of life and a consequent “quest for self-realization”. This is the path by which sharing, as a type of communication, becomes related to authenticity, self-understanding, and the basis for the conduct of intimate relationships.

The other path remains closer to the pre-metaphorical sense of sharing as dividing, and can be traced through the brief history of computing. When time-sharing was invented, and named, it was a technology that divided up a computer’s computational capacities among multiple users; the computer’s time was being dividing up and allocated to different users. Later, disc sharing was developed. Here, the “sharing” part of the term referred to the fact that the disc was shared by more than one user; it was held in common. Likewise the idea of file sharing, at least in its first instantiation: file sharing meant making a file accessible to others (not duplicating and distributing it, as most people understand it today).

The conjunction of these two paths came surprisingly recently, not much earlier than 2005, in fact. This is when social network sites recruited the concept of sharing to describe and promote what we do there. Some of this was no doubt opportunistic, harnessing their businesses to the pro-social implications of sharing; some of this was organic, as for computer scientists the idea of sharing files, images, and so on, was already common currency, though lacking in a normative dimension.

Your references here to the Care Bears is a good reminder that those of us coming of age in western society are taught to share our toys, our feelings, at an early age. When we use sharing in relation to other practices -- for example, in the phrase, “the sharing economy” -- we tap something very primal. Some authors you reference go so far as to assert that sharing is a fundamental aspect of human nature -- hardwired into our very being -- but we are often required to unlearn those sharing impulses to operate within competitive capitalism and its struggle over resources. How might this reliance on a concept so bound up with childhood development render us blind to hidden agendas at play within the “sharing economy”?

The terminology around the sharing economy has been under scrutiny for a while, and my position on this is not a simple one to lay out. To be sure, there are companies within what is called the “sharing economy” that want potential customers to associate certain values with them (the values of sharing) while operating according to the logic of capitalism. To be sure, there are exploitative practices afoot within the “sharing economy”, and they must be criticized and rooted out. Also, it cannot be denied that the word, sharing, is an important weapon in the marketers’ arsenal. Accordingly, one could, if one wanted, compile a list of practices that are compatible with sharing, and a list of practices that are not. Then, one could confidently say whether a certain service is “really” about sharing or not. For instance, one might want to argue that if money changes hands, there is no sharing going on.

This, though, is not my approach. Partly this is because language is dynamic and I do not find it useful to say that this or that practice is “really” sharing, which is to reify words (in other words, my approach is a pragmatic one). For instance, I have not read a critique of sharecropping (where the tenant pays the landowner by giving him a share of the crop) that says it is not really sharing.

More than that, though, I think that the proof of the pudding is in the eating. What I hope the book shows is that there is much to be gained from pushing beyond the question of whether practices are “really” sharing. I try to historicize and culturally contextualize our present concept of what sharing “really” is, and I think an outcome of this is the realization that uses of the word, sharing, that are critiqued for not “really” referring to sharing, and those very critiques themselves, have common cultural origins. In other words, when I read that something is not really sharing because it involves money and is not an authentic type of communication, say, I recall that the type of authentic communication that we call sharing emerged, and was called sharing, as part of the formation of a self that was suited for modern, capitalist society. The word, sharing, today has a distinct set of meanings that quite simply was not enacted previously when the word was used. Thus, in the book I argue at some length that to apply the word “sharing” to prehistoric hunter-gatherer societies is to be anachronistic.

Nicholas John is a Lecturer at the Department of Communication and Journalism, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research interests include technology and society, the internet, social media, sharing, and unfriending. He is the author of the award-winning book, The Age of Sharing. This book offers an innovative approach to sharing in social media, specifically by linking it to sharing in other social spheres, namely, consumption and intimate interpersonal relations. The book won the Best Book award from the Israel Communication Association, and the Nancy Baym Book Award from the Association of Internet Researchers. Nicholas is also interested in disconnectivity, which he sees as a neglected aspect of digital culture. In particular, he is fascinated by Facebook unfriending, particularly when it is politically motivated. He sees unfriending as a new political and social gesture that we know very little about. His teaching looks at the complex interrelations between technology and society.

The case studies in the book also help us to map some other kinds of borders, as culture jamming rhetoric and practices are absorbed by Madison Avenue on the one hand and the art world on the other. The tendency is to read such examples primarily as a form of co-optation, but are there also ways that these border-crossing help to spread countercultural messages to new publics?

Definitely so, yes. Co-optation is certainly the buzz word here. The ad world makes use of culture jamming practices because they are rhetorically powerful. At the same time, some talented designers who work on Madison Avenue moonlight for organizations like Adbusters; so, if there ever existed a firm boundary between the subcultural domain of culture jamming and the media industry, it’s not there anymore. Yet this doesn’t necessarily need to be negative. Think of the Truth campaign by professional ad agency Crispin Porter + Bogusky. Michael Serazio’s chapter in our book describes how traditional anti-smoking campaigns often failed to move their target audiences, because they only strengthened the attraction of that which is forbidden. So CP+B took an alternative route by using the rebellious feeling of culture jamming tactics in its Truth campaign—for instance, by dumping a thousand body bags outside a tobacco company’s headquarters.

Moritz, your contribution here comes out of your larger project of providing a cultural-history context for thinking about The Simpsons. What does this particular example teach us about what happens as countercultural practices enter the commercial mainstream? Can The Simpsons still be subversive if it gets produced and marketed by Fox? Or is it another example of “the conquest of cool”?

You’re pointing to the old dilemma, Henry ;-) Can a cultural phenomenon as commercially successful as The Simpsons be at once a commodity, and thus subject to the logics of capitalism, and still be considered subversive? Well, in contrast to “the conquest of cool” argument which echoes the Frankfurt School’s cultural skepticism, I would argue it can. Subversion isn’t exclusive to productions operating below the radar of mainstream culture, especially at a time when we see how mainstream culture seeks to integrate virtually everything that connotes subcultural appeal. I’d say that what counts is the effect a certain cultural artifact has. So, yes, The Simpsons is definitely another example of neoliberalism’s cashing in on the cool, but, on the other hand, within its unusually long history, the show has had so many moments where it has torpedoed the dominant capitalist culture, albeit in the form of media representations. There is one episode where the show depicts a “Sprawl Mart” store to satirize the consumer culture and labor conditions disseminated by big box stores such as WalMart; in another instance, The Simpsons has humorously critiqued the plastering of public space with Starbucks coffee shops. The show’s viewers understand this as subversion and appreciate this element of the series. My favorite example here is when The Simpsons featured the social media platform Facebook on the series in 2010—at a time when the show became quite edgeless, Simpsons fan-critic Charlie Sweatpants complained about how uncritical this representation was. He found their show lacked in subversive intensity, a quality he and many other Simpsons fans previously found to be there.

Marilyn, one of your contributions was to interview or otherwise solicit responses from some of the artists and activists currently practicing in this space. How useful did these practitioners find the theory of culture jamming for explaining what they are doing through their work?

I sought out the interviews, work and commentary by these artists and activists to help flesh out and illustrate the concept of culture jamming, rather than the other way around. Most of the people I talked to have a long history of developing their artistic practices, and whether they explicitly conceived of themselves as “culture jammers” didn’t matter that much to me. Some saw themselves primarily as pranksters, others as artists, political activists, or alternative community builders. We believed that including the voices of artist-activists in our collection—in addition to those of academic theorists and critics—would offer valuable insights to our readers on the range of practices that we consider culture jamming.

Some critics have argued that culture jammers substitute a symbolic or semiotic polics for actual efforts to change the world. How valid do you think this criticism is? Are there examples where culture jamming has, in fact, led into more immediate forms of social action and political change? What might we learn from those examples?

Ascertaining the immediate effects of activism is a thorny affair. While there may be some value to the warnings abou semiotic play (including “clicktivism”) substituting for political action, several of our authors explore ways that participatory culture jamming can form a sort of on-ramp to other forms of activism. Furthermore, as Rebecca Solnit explains in this recent piece, we can’t know precisely what effects any kind of protest action or intervention will have on future movement work. Take, for instance, Occupy Wall Street, which was initially sparked by a call from Adbusters, but was then taken up by organizers in New York City and later around the world. Some argue that OWS failed, because it didn’t issue clear demands, or change laws, or elect any candidates. And yet, as Jack Bratich explains in his chapter, OWS was a powerful meme generator, and it left us with lasting terminology (“We are the 99%” and “Wall Street vs. Main Street”) that has informed public discourse in the US since. OWS also created or strengthened community ties that were later activated, such as the “Occupy Sandy” citizen relief efforts in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy in 2012.

Moritz Fink is a freelance media scholar and author. He holds a doctoral degree in American Studies from the University of Munich, and has published on contemporary media culture, popular satire, and representations of the grotesque. His most recent book is the co-edited volume Culture Jamming: Activism and the Art of Cultural Resistance (NYU Press, 2017).

Marilyn DeLaure is an Associate Professor of Communication Studies at the University of San Francisco. She has published essays on dance, civil rights rhetoric, and environmental activism, and is co-editor of Culture Jamming: Activism and the Art of Cultural Resistance (NYU Press, 2017).

Recent Posts

Publications

Powered by Squarespace.