Revisiting the Concept of "Sharing": An Interview with Nicholas John (Part Two)

/To what degree was sharing part of the early hacker and counter-culture ethos which shaped our understanding of cyberspace? To what degree might it have emerged from the science and technology culture of research institutions such as MIT and Caltech which also placed a value on the open exchange of information?

It was absolutely part of the early hacker culture, and indeed of early computing culture. However, I find claims that the internet, or cyberspace, has always been about sharing to suffer from the same anachronism as claims that prehistorical hunter-gatherer societies were about sharing. This is because I’m interested in the use of the word, and the word did not come to represent the internet until the mid-2000s. The key text on the counter-culture’s role in the cultural signification of the internet is Fred Turner’s From Counterculture to Cyberculture. What I find worthy of note is that nowhere in the book does he talk about sharing as value of the internet; nor, incidentally, does Howard Rheingold in The Virtual Community. Today we understand cyberspace in terms of sharing, but we did not thus understand it even as recently as the early 2000s.

The second part of this question is, in my reading, an empirical question, which one would answer by looking through the archives of those institutions. Did they talk about sharing? Is that how the open exchange of information was discussed? I don’t know, but it could be interesting to look into that.

Why has sharing become the prefered language for talking about what we do when we participate on social media? What other potential frames might we consider for thinking about these activities?

There are three main reasons for this. The first sees “sharing” as emerging organically from the field of computing, where it has long been a term in use (as I mentioned earlier in relation to time sharing).

The second is that the term, sharing, covers so much. It refers to both the distributive and communicative aspects of sharing, and it incorporates a wide range of other terms that might be used in describing social media activities, such as “express yourself”, “post”, “connect”, “socialize”.

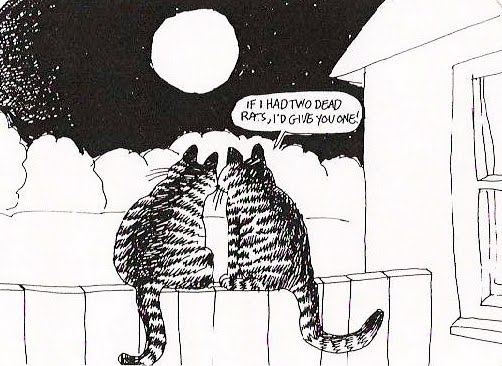

The third reason is that “sharing” has such positive connotations, encapsulated in the phrase, “sharing is caring”.

Taken together, these reasons point to a term that is both an organic part of the world of computing, and that has been leveraged by social network sites’ PR people. If you look at the front pages of the major SNSs over the first decade of the century (something I have done so that you don’t have to), you can see the word “sharing” becoming more widespread over that time, but particularly between 2005-2007. Facebook played an important role in this. They adopted the concept of “sharing” in 2006, which seems to have pushed other companies to present themselves in that terminology too.

This suggests that the term, sharing, came relatively late to digital culture, which begs the question, what other frames were used prior to that point?

One significant frame was that of “gifting”, but I see “gifting” and “sharing” as quite different. First, I would note that “gifting” and “sharing” are different in that the former was a theoretical concept used by scholars to describe activities they were witnessing (making music files available to others on Napster; creating websites), while sharing became the term used by social network sites to describe participation on them. So actually “gifting” wasn’t the term used by participants, but rather by observers.

Be that as it may, gifting refers to the distribution of goods, even if they are immaterial goods. Sharing refers both to the distribution of goods and to a form of interpersonal communication. Because sharing as a type of communication implies honestly, openness, authenticity, and more, it is far wider than the notion of “gifting”. To say that someone is sharing is to suggest that they are giving something of themselves. More than gifting does, it implies caring, perhaps even altruism.

The phrase, “the sharing economy,” has been applied to everything from Uber to Wikipedia. How can we make meaningful distinctions between the different forms of “sharing” involved here and the ways what gets shared does or does not become part of a larger “economy”?

There have been plenty of attempts to make this distinction. Lessig talks about me-regarding and thee-regarding economies, and about thin and thick sharing economies; Belk talks about sharing in and sharing out, and also about sharing versus pseudo-sharing; in a slightly different context Haythornwaite talks about crowds and communities. There have also been other efforts to shift the terminology, perhaps most notably Hillary Clinton’s promotion of the term “gig economy”.

I think, though, that the horse has bolted, and that the term “sharing economy” is here to stay. More than that, I think that the very word “sharing” may get another layer added to it. When attending a sharing economy meet up in Manhattan, one of the panelists spoke of different models – sharing for free, and sharing for money. None of those in attendance objected to this (perhaps they were being polite), which raises the possibility that “sharing” will also come to mean something like “using an app to rent out possessions”. If this happens, does that mean that there will be no more sharing (the “good” kind) in the world? I don’t think so, but I’ll save my thoughts on this for the final question.

You discuss sharing in the context of a therapeutic discourse, which links it to notions of individual wellness and social health. Yet, could we also see the concept at work in political movements, like the feminist consciousness raising sessions of the 1960s or the giving of testimony in a range of social movements across the 20th century? This political notion of sharing involved recognizing commonalities in social experiences as the basis for framing larger critiques of the current order.

I don’t feel particularly qualified to comment on the feminist movement of the 1960s or the giving of testimony in other contexts. What I can say is that in these contexts it seems that the authentic individual experience is given voice. By hearing others’ voices, one may feel empowered – it’s not just me! – and by giving voice one may also feel empowered – this is who I truly am! These instances, then, seem to belong as much to the therapeutic discourse, which extends far beyond the therapist’s clinic.

I would add here that my investigations into the origins of the therapeutic sense of “sharing” lead back to an evangelical group that was active in the US in the 1920s and ‘30s. Called the Oxford Group (no relation to the university), its key practice was as follows: members would sit together in someone’s parlor or drawing room and take it in turns to publically confess their sins. This practice was called “sharing”. Two alcoholic members of the Oxford Group adapted this practice to allow other alcoholics to talk about their experiences in a non-judgmental setting. This became Alcoholics Anonymous (where participants are famously thanked for sharing), which, to the best of my knowledge, is where the ideas of sharing adopted by countless other groups and organizations – some of them more psychologically oriented, and some of them more political – were institutionalized.

Nicholas John is a Lecturer at the Department of Communication and Journalism, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His research interests include technology and society, the internet, social media, sharing, and unfriending. He is the author of the award-winning book, The Age of Sharing. This book offers an innovative approach to sharing in social media, specifically by linking it to sharing in other social spheres, namely, consumption and intimate interpersonal relations. The book won the Best Book award from the Israel Communication Association, and the Nancy Baym Book Award from the Association of Internet Researchers. Nicholas is also interested in disconnectivity, which he sees as a neglected aspect of digital culture. In particular, he is fascinated by Facebook unfriending, particularly when it is politically motivated. He sees unfriending as a new political and social gesture that we know very little about. His teaching looks at the complex interrelations between technology and society.