I’ve been re-serializing Vattu on Webtoon, the big Korean webcomics. I don't have to explain that to you. I look at the numbers on there, the millions and millions of people reading some of that stuff and that those numbers are so big that that is what the medium is for them. There is a huge number of people just on that platform making and reading that I just wasn't aware of until a little while ago.

So, I feel like that's kind of what webcomics is now. And what does that mean? That means that people making comics for that platform and tending to not put them anywhere else are tending to not have their own place and their own audience and brand building project outside of Webtoon. That just leads everybody into the same rut that YouTube creators or whoever is on where they're just trying to appeal to the inscrutable audience dynamics and algorithms of that platform and they're trying to not get their content banned because they mentioned or deal with any particular narrative content. And then they try to make a living just off the back of that platform, which is apparently feasible, and people do it. I have like 7000 followers on there and as a result, I was not aware of this, I get 100 or 200 bucks a month in ad sharing. That's great but you need an insane amount of readership there if you're going to make a living off of their ad revenue. Or you need to be contracted to do their Webtoons originals or whatever. It's just not self-publishing. It's great that platform is there and that there's so many people there. And people are doing great work on it, but it's compromised. It could shut down at any minute. They could kick you off at any minute.

The amount of money that you could make doing your work it just pales in comparison to what you could do, in theory, if you could bring that audience somewhere else, and just sell 1% of them a book or a t-shirt or whatever. I don't know, I'm kind of rambling but that's the shape of the shift as I see it. It sounds like I'm being judgmental of people operating in that scene as it is now, but I don't mean to be because it's kind of like that's what it is. There's so many people there that how could you not? We're so divorced from the idea of artists having their own Internet spaces that why would it not seem self-evident to you that the only thing to do is just build up as much of an audience on Webtoon as possible and hope for the best? It just puts people in a really, really delicate precarious position and it's kind of self-publishing but it removes a lot of the benefits of self-publishing as I have seen them.

James Lee: Yeah it's been an interesting shift to observe when we think back to the earlier with the Wild West days of the Internet there was this old idea proposed by Scott Mccloud, comic theorist, about the infinite campus basically that with this great new tool, the Internet, that we would be liberated from the constraints of the physical and there would be this golden age of people experimenting in weird and interesting ways. But I think we've seen over the years there are constraints that people consider. If you want to print for book, for example, if you want what you made to be available in book form, then you have to consider print dimensions, resolution size. And now with Webtoons you have this long vertical scrolling format designed for the mobile experience. So it's another kind of set of constraints and maybe more limiting and not necessarily let's say as liberating as other paths that could have been taken.

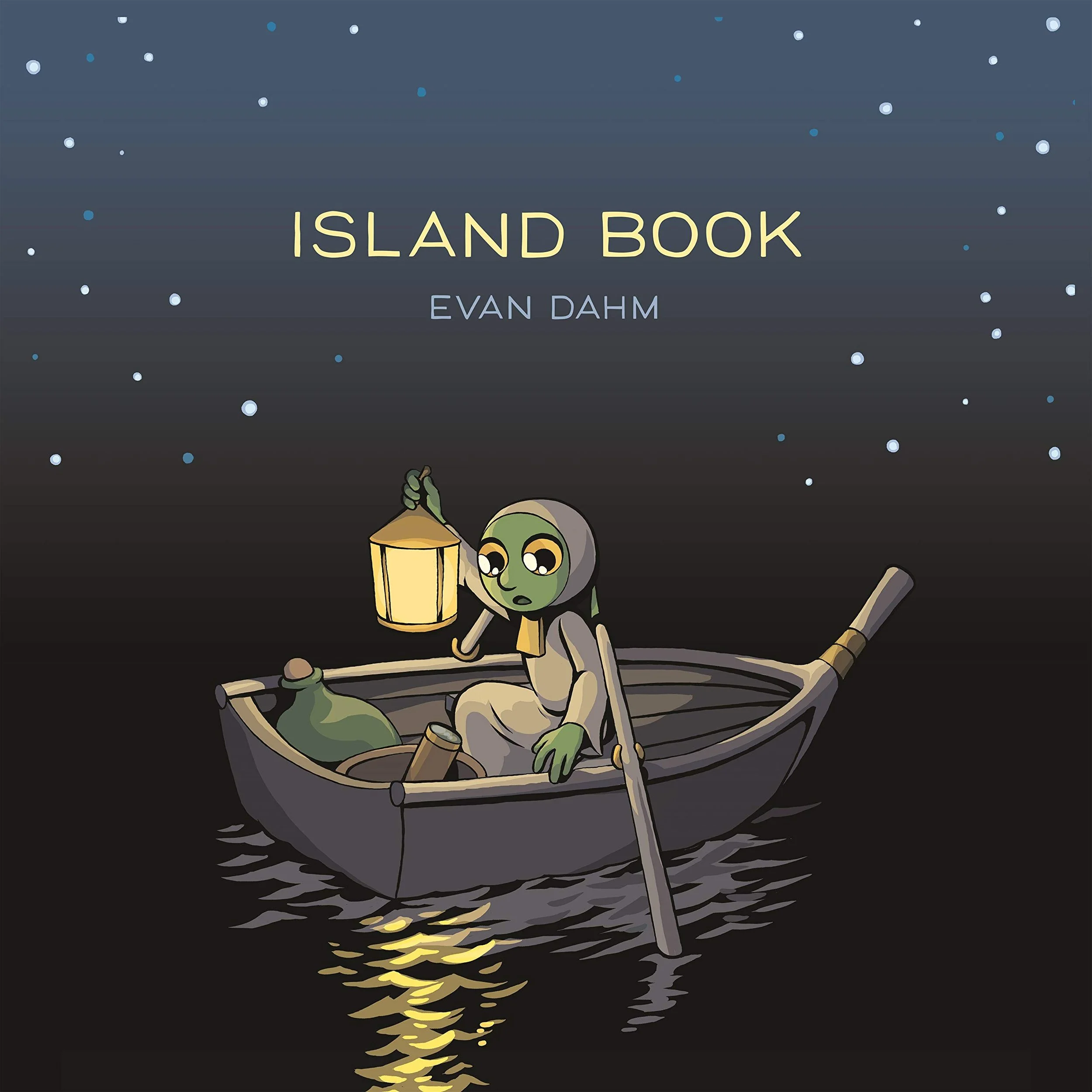

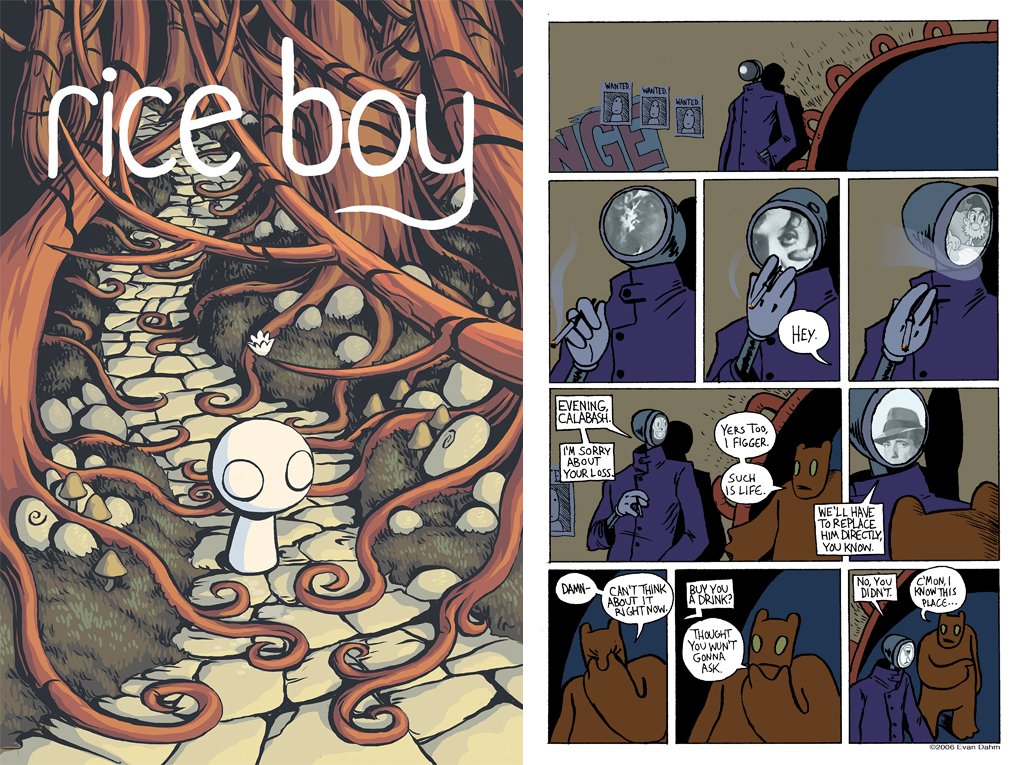

Evan Dahm: The thing is I'm kind of an apologist for that. I think that he was basically right. The infinite canvas thing got used in a few like gimmicky token ways throughout the years. I made Rice Boy in 2006-2008. It's formatted as a book. It does not take advantage of the infinite canvas Internet thing at all. But structurally that book could not exist if not for the Internet. You can't just publish a 500-page comic book anywhere but the Internet. There was no publisher would have done that. That is a kind of infinite canvas type thing as comics have always been limited by not only the physical size of the pages but the means of their production and distribution. I think it's important to keep in mind that maybe comics on the Internet haven't taken advantage of that physical trim size limitation being lifted, but certainly they have profoundly taken advantage of a huge opening up of the limitations by means of production.

James Lee: Even with Webtoons we can think of the infinite scroll as being kind of an application of this.

Evan Dahm: Yeah, and there's sorts of stories all the time being produced now that could not have existed were they subject to all of the constraints that existed in form before the Internet.

James Lee: Yeah, it's interesting because there are a lot of key issues going on now, but also people can make the argument that now is the best time to get into this stuff. You can just make anything you want and post it on any number of platforms. Burying some of these issues of censorship and other factors.

Evan Dahm: As long as you're as long as people have in mind that you can put it everywhere. I see kids - that's rude of me – I've seen a lot of people agonizing over “I'm making this comic, should I put it on Webtoons or whatever?” You should put it fucking everywhere. Why not? You're trying to get it out there. These are these are platforms that you can use. There's no there's nothing wrong with it. Just don't think that any one of them is going to make it all happen for you.

James Lee: Yeah, I think also related to this is that the field is open to everyone. So, in essence people feel they have a lot of competition with people with more developed skills. You have professionals, aspiring art students making webcomics as well. Big departure from the early days when this very small kind of amateurish works that existed back then compared to now. Could you talk more about this idea of polish which you've spoken about previously?

Evan Dahm: Oh yeah, I was just talking on Twitter about that. A lot of it is that everybody's on the Internet now and everybody who's making art is putting it there and there's just so much of it that it kind of pushes everybody in a different way than it used to. But also, I think that we, I don't know, I feel like audiences are expecting a certain level and type of polish in a way that they weren't before. And I don't know if that's good. I feel like audiences are expecting a high budget movie type of polish from a piece of art made by an individual and I don't like that. I have this sort of loose and indefensible theory that we're, at least in America and maybe at least in the Anglosphere, we're kind of atrophying our understanding or we're losing our understanding of drawings as such. We're not really understanding what goes into them what decisions are being made what they are. So, as a result of that maybe we expect drawings to have an extreme level of polish or kind of internalized embarrassment of the fact that they're drawings or something.

I think about American animation and how animation for kids is allowed to be really visually inventive and rich and visually smart, to fully lean into drawings as a beautiful thing to be explored in their own right. Animation for adults in America is stuff in the Family Guy mold where there's nothing there. It's just making a joke of the fact that it's a drawing – like “isn't this show funny? Isn't it funny that it's a drawing?” – and it's kind of embarrassed to even explore the possibilities of drawing. It is made of drawings and that's enough. It was a very loose kind of idea…

James Lee: I think definitely there is something there. You look at these animations for adults, things like Family Guy and others in that genre, and it feels terrible in a way that you don't see with cartoons aimed at kids.

Evan Dahm: Right so there's the sense that emerges out of that, I think that drawings are for kids or finding beauty and interest in drawings is something that adults should not do. Adults are supposed to look at realistic highly developed images.

James Lee: Yeah, it's a very specific way of thinking of polish that closeness to reality is the metric of, say, artistic skill or quality.

Evan Dahm : Exactly, closer to the optical even. I find that deadening because you're never going to, I don't know, we don't live in reality. We live in our little poetic socially constructed image of reality. This is connected to that objectivity and worldbuilding thing I was talking about. How are you going to objectively represent something that everybody has their own perspective on? There's optical reality, there's the reality that the camera shows us, but I think we do a disservice to our visual engagement with the world if we treat that as the one thing that every representation has to go for.

James Lee: Why do the job of the camera when the camera already exists?

Evan Dahm: Yeah, and we don't live in that reality. We have optical input from the world but there's a lot more to our visual experience of the world than that, I think, and there should be in our production of images too, I think.

James Lee: Okay, so building on this, over the years we've been seeing more encroachment from outside players who have been more interested in profitability in the spaces and tools used by independent creators like yourself. We have cases such as Amazon I think back in 2018 at Small Press Expo showcasing their original print-on-demand service. We have Kickstarter’s foray onto the crypto roller coaster. And, more recently, we had the Toronto Comic Art Festival (TCAF) giving space to NFT art and being met with backlash this past year. So, what are your thoughts on this trend, especially in relation to independent art?

Evan Dahm: Generally, it feels kind of bleak. The NFT thing particularly just feels like a really apocalyptic cashing in thing. It's so nakedly wasteful and all of the sort of futurist arguments for its miraculous capabilities, I think I am smart enough to be able to tell if there's something there or not and I just don't see it. So it just feels totally just like nihilistic cash grab type people. The Pink Cat, the NFT person who was invited to TCAF and then disinvited has just I think cut and run like she just vanished from all for social media platforms. So, what is that a rug pull? Is that what people -

James Lee: Yes, that's the term. A lot of these scam terms are becoming very popular these days.

Evan Dahm: Yeah, and that’s related but I guess that's a separate thing from Amazon buying all this stuff. That’s related to what I'm talking about with the Internet being locked up, and all these platforms. It's exciting to see people pushing against that and it's exciting to sometimes have this sense that there's this broad backlash against it, that people remember that they can do things outside of these platforms, that self-publishing is a thing in various ways. I don't know what to make of it really. I am encouraged that there seemed to be a lot of people who understand that it's happening, and that you can operate in spaces outside of it to at least some extent. I try not to get too doom and gloom about it with myself, I guess.

James Lee: Yeah it feels very easy to fall into this negative cycle, especially when it feels like it's inescapable. As much as you try to ignore terms like NFT and crypto they just keep coming up.

Evan Dahm: Yeah it's inescapable, but I feel like for me a lot of a part of why I'm able to not get sucked into it, maybe just my disposition, but also it feels good to be making something consistently that is out there in its own little space and that is entirely mine and that I'm not dependent on any of these – I mean I am dependent on platforms – but I doing this thing separate from Amazon and all this stuff. People are reading it and I feel like I'm doing something that helps me.

James Lee: So, compromise is a recurring theme that you mentioned, at times, specifically the kinds of compromises, you have to make to keep doing what you want to do, and to survive. At times, this might mean buying into corporate structures, whether that be working with them or engaging with others on their terms, on the terms set by those structures, such as the walled gardens that you mentioned before. So, while we may be critical of these, there can also be no functional alternatives, especially when it comes down to a matter of survival. Can you speak more about this kind of ambivalence and how you navigate it?

Evan Dahm: I'm doing this as a career so there's an aspect of me that is just a totally cynical striver about it. I can try to navigate it with principles or whatever, but there is no way of having a career doing it where I stick to all of them or where I don't engage with any part of the culture or the Internet that I don't like. I think it's been kind of easier for me to wrap my head around that because I've been working in comics and that medium has always been thought of and I've always thought of it as pretty compromised from the jump. It's a commercial medium. It's a commercial illustration turned into entertainment storytelling. There's so many different aspects of what I'm doing that proceed from these rich traditions of compromise and commodification. I don't know how else to look at it really. When I was in college, my minor was in studio art and at that time the school I was at the arts department was entirely aimed at the fine art world which has always been kind of just frustrating or uninteresting to me. I learned an awful lot like technical drawing and stuff doing that, but the idea that there's any pure art free from compromise or engagement with the material world is just silly and frustrating to me. And it was it was kind of funny I guess to be working on Rice Boy, this very tacky pop-y illustrative thing, at the same time as I was taking classes in this program that just had no interest or understanding of illustration or comics or anything that debased. I had one more thought, give me one second.

James Lee: Okay sure.

Evan Dahm: Oh yeah and I've been thinking about what it takes for a thing to materially exist. We're making this work within capitalism. Either I'm compromising in all sorts of ways and trying to make it something that will make me a living, or I'm independently wealthy, or it doesn't get done. I want it to be read. This is how I engage with the world in large part. This is how I understand the world and how I talk to far more people than I will ever talk to as an individual so how do I fit that into the world? I have to make it pop cultural, make it intelligible, and sort of compromise to that extent. And then I have to make a living doing it however, I can. That's the only way that it can exist. Because if I don't think about it like that, then I'm just privileging work made by people who already have the money, basically. I'm not a rich kid. That's not the position I've ever been in. This is my job.

James Lee: Yeah, that's an excellent point that even the works that try to be abstract and removed are made in a context which enable that, and maybe that means coming from a family of wealth which we are not all necessarily privy to.

Evan Dahm: I guess I'm lucky that the sort of thing that interests me is kind of pulpy and a mass audience type thing.

James Lee: Well, we got to work within the system we're born into. Even if you want to change it, we won't change it overnight.

Evan Dahm: Mm hmm.

Closing Thoughts

James Lee: Okay, so home stretch. There are just a couple questions to wrap up. What are you into these days? It could be anything. You mentioned some of the manga you're reading earlier.

Evan Dahm: Oh yeah, I've been thinking a lot about Dragon Ball. I read all of Dragon Ball a little while ago and I can't stop thinking about it. I've been reading a lot about self-publishing. Different, earlier, obsolete areas in comics self-publishing. I've been reading a lot of interviews with Jeff Smith, who made Bone. I've been reading Dave Sim’s big weird argumentative self-publishing diatribe with the caveat that I do find that guy pretty unhinged and despicable, but he occupied a very particular space in self-publishing like periodical self-publishing when the direct market was a new thing for comics. I've been very interested in that.

I'm thinking of maybe doing some sort of limited podcast where I interview people about their approaches to self-publishing in different eras because I know people who have engaged with that at different times and it's interesting to see. I'm really trying to wrap my head around, at least in a big, vague, vibe-oriented way, wrap my head around how working independently works in different circumstances. The sort of thing that I'm doing is very different and it's always been very different from a self-publisher like a Jeff Smith, but a lot of the dynamics are the same on some level, like the culture around the art.

What else have I been into, I've just finished Future Boy Conan, Miyazaki’s early series from 1979 which I just loved it so much.

James Lee: What do you like about it?

Evan Dahm: It's very focused and the pacing is incredible. It's telling one big story basically nonstop continuously and each episode mostly is focused around a simple challenge to be undertaken. It doesn't hugely overreach. It's not trying to do something big and complicated and particularly because it's Miyazaki. I'm used to see his stuff in very expensive opulent motion picture animation. It looks very cheap and limited, but it does it all so confidently and beautifully. I just loved it. You rarely see serialized storytelling that fits together that well, in my opinion. I recommend it.

James Lee: All right, I'll add it to the list. The next question is: what would be your dream project if you had unlimited time and resources? It could be webcomics, it could be anything else. It could be something you're currently working on, or something you want to see down the line, big or small.

Evan Dahm: Unlimited time and resources… If it's literally unlimited, I guess it would be – I don't know – just the same sort of thing I'm doing, but just taking more pop cultural space. I would make a big traditionally animated movie and just make it available in every possible place. Or I would start an animation studio. No, I don't know. In reality, my dream project is probably the thing I'm starting after Vattu, which is a… Well, the reason I'm thinking so much about the material conditions for art and how a thing can't exist unless it can materially exist is because I'm trying to at least understand how I'm going to make it happen in a self-publishing way. And I’m trying to approach the story and the means by which I published the story in a smart and eyes open sort of way. I want to continue to self-publish these big expansive long-term projects in a way that can work and they can continue to exist in the Internet as it is. But that project is a lot of what I am thinking about and I feel like I can approach it in a way, where I am mobilizing a lot of what I’ve learned about serial storytelling and sort of starting over but still building on a lot of the stuff. I’m very excited about it. I've written a lot of a lot of it.

James Lee: And I'll be looking forward to seeing it.

Evan Dahm: I appreciate that.

James Lee: So any words, in closing, you want to convey to let's say people who want to express themselves through our but feel intimidated or overwhelmed in terms of figuring out where to even start.

Evan Dahm: It feels like the most important thing is that you know what you want to make. It might be kind of difficult to figure out what that thing is in the most personal and honest way but hold to that and don't worry too much about what people will say about it, or how it'll fit into the world or whatever. The main thing, the engine, that all makes it happen is just doing the thing that they intensely want to do and not really giving a shit about how feasible it is, or if people like it or whatever, to an extent. And that to me is the value of working in comics, in particular, because you can do it with one person or a very small team for no money and it's a visual medium. You can do fucking anything.

James Lee: So basically, to make comics you got to make comics.

Evan Dahm: Yeah, and everybody has their thing. Everybody has their own angle. I guess that's it.

James Lee: Okay, so that's all the questions I have. Let me stop the recording here.

Evan Dahm: Cool, thank you for having me.