Celebrating Rice Boy and Vattu: An Interview with Web Comic Creator Evan Dahm (Part One)

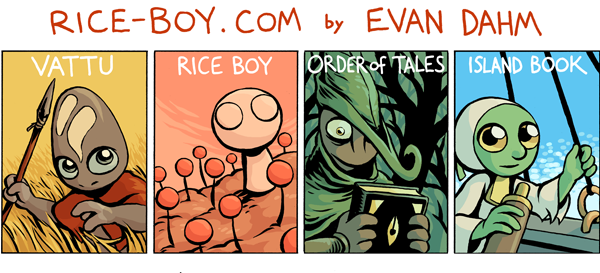

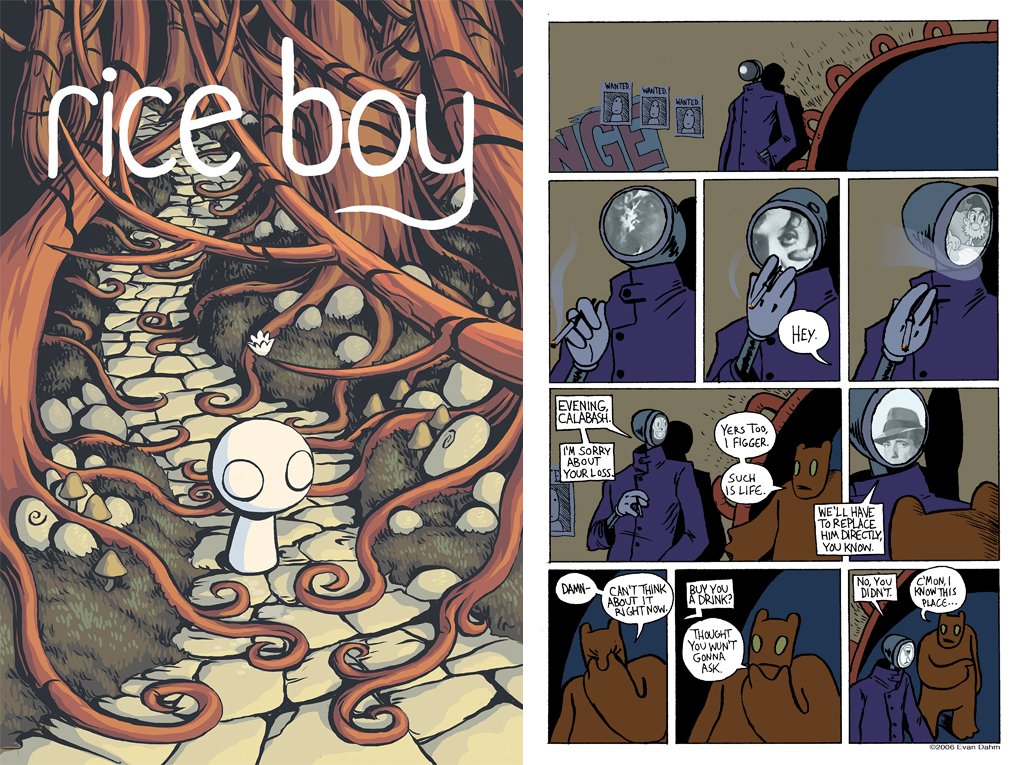

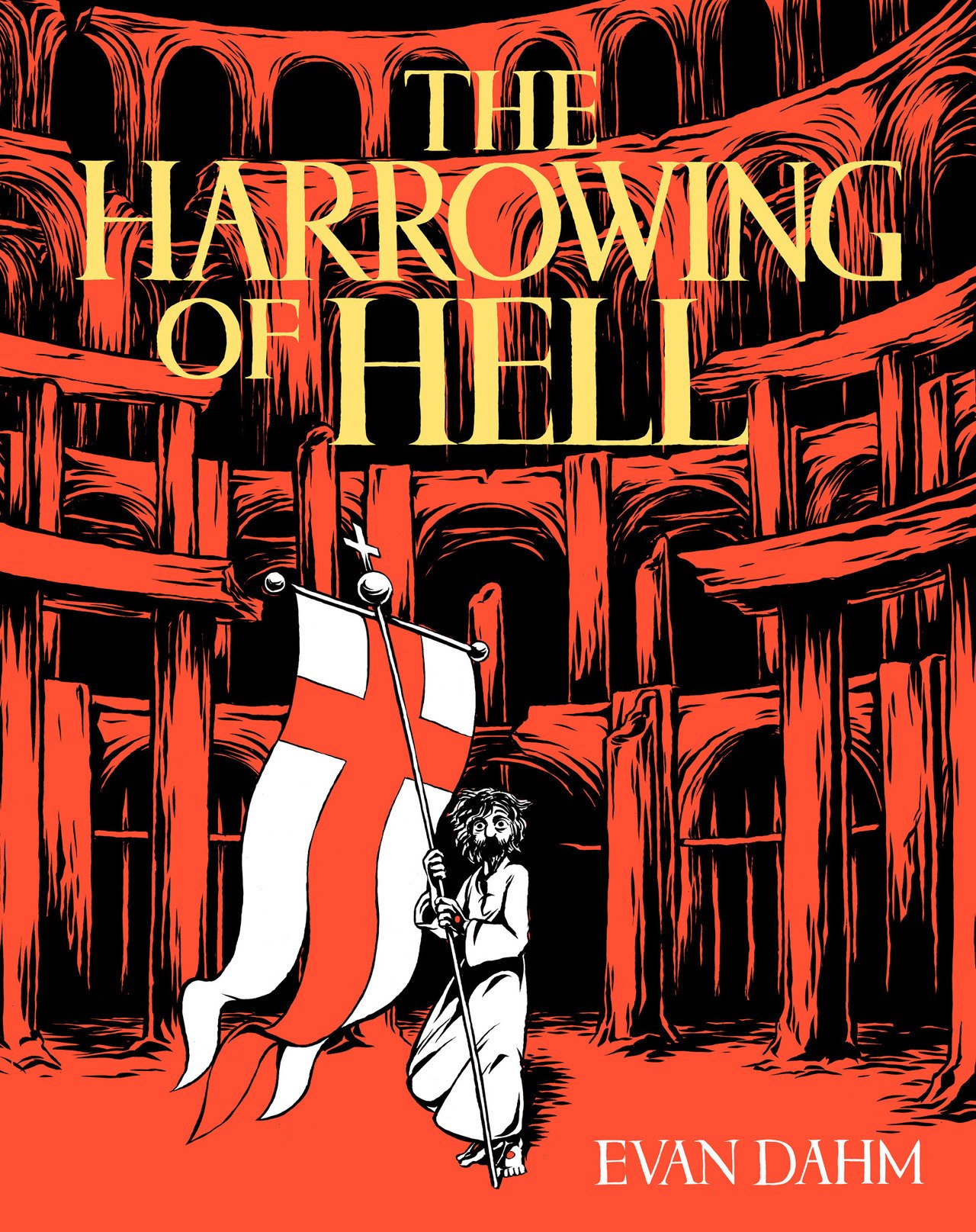

/Evan Dahm is an independent artist and longtime webcomic creator. In 2006 he began Rice Boy, a surreal fantasy webcomic and has since self-published several fantasy epics set in the same universe. His body of work also includes published works such as the Island Book series, a high seas adventure, with First Second and The Harrowing of Hell, a retelling of the time between Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, with Iron Circus Comics. In 2010, Dahm began Vattu, a story about a young girl’s conflict with an expanding empire. 12 years and nearly 1,300 pages later, he completed Vattu on September 12, 2022. As a longtime webcomic creator, Dahm has been on the frontlines of the changes in independent webcomic production. From the early days of small, personal websites to the rise and concentration of large-scale social media and aggregator platforms such as Webtoons, Dahm continues to create his own unique work. Even as he adapts, Dahm retains his personal voice in his art. In this interview, Dahm discusses some insights into his approach to storytelling, his experiences with making webcomics, and the current state of and issues in the field with fellow comics artist James Lee. Dahm’s next project, 3rd Voice, begins in December 2022.

Here’s the audio version of the interview. Passcode: &AYyWw7*

James Lee: I thought to start off maybe we could start at the very beginning with Rice Boy, your first webcomic. Something you mentioned in previous talks and videos you've done is that you mentioned how your start in webcomics had an element of luck involved. What kind of factors do you think made that time when you self-published rice boy the right moment?

Evan Dahm: I can only really determine this in a kind of a loose retrospective way, but the big transition that I’ve lived through in my adulthood, the big transitions in my life, have been the Internet emerging and becoming more and more accessible and then the really strikingly rapid boxing out of everything into corporate social media platforms, the Web 2.0 shift.

In retrospect, it feels like there was this window of, I don't know, probably under two decades when there were enough people on the Internet, and there were enough people aware that they could sort of take charge and just make a place of their own on the Internet, that it was a sustainable thing to self-publish your idiosyncratic little thing in that particular model.

But then, as the Internet has gotten more of a thing that everybody is on, what the Internet is to everybody is just Facebook or Twitter or Instagram or whatever. It's just funny that it doesn't even seem to occur to people that you can have control of any space there, that anything can exist outside of these corporate platforms.

James Lee: It's definitely been interesting to observe.

Evan Dahm: How old are you? Do you mind if I ask?

James Lee: I'm 34 right now.

Evan Dahm: Exact same.

James Lee: I’ve observed the same kind of shift from the hopes and dreams of the early Internet to where we're at now.

Evan Dahm: Yeah.

James Lee: I want to continue that line of questioning soon in a bit so hold that thought. Before we get there, though let me ask you a little bit about your process. You primarily use a brush in your work, which has a great expressive quality to it, and it really reflects the human hand behind the work itself. In your documentary, Making Vattu, you spoke about the improvisatory quality of the brush. Can you talk a little bit more about that, and maybe perhaps how it informs your own values and approach to art?

Evan Dahm: I try to sort of be reasonably pragmatic about it. I'm very aware that it's easy to slip into being a little bit precious or superstitious about technology and stuff. The way that people unfairly valorize work in physical media over digital illustration, I just don't think that's the right way of looking at it. But I do have a strong sort of automatic revulsion towards a lot of technology. It takes me a while to acclimate to it.

I like traditional drawing skills, feeling in touch with tools and aesthetics of drawing that have been in places like commercial illustration for 100 years. I like feeling in touch with that. I like learning skills where I can sort of understand the history of them. And just on the granular level I figure any physical tool is going to just produce more randomness and imperfection in a way that I like. It takes an enormous amount of muscle control to use any kind of brush in a way. It's a very particular type of skill and I don't want to lose it.

While I'm working on a tablet or whatever there's pressure sensitivity, there's a lot of subtlety and range that can be done with those lines, but I haven't really learned how to do that. I can draw competently on a tablet because I can draw but it's dry. With a brush at such an intensely high resolution and degree of muscle control, you can do literally an infinite number of lines. It's important to me to maintain practice in that.

James Lee: At some points it's as if it's a little too liberating and a little bit of constraints can sometimes help define your work.

Evan Dahm: I think so because if you're constrained in some sort of way, then you can more fully understand the huge range of possibility within that constraint, I think.

World Building and Storytelling

James Lee: This might be a good opportunity to talk more about world building and storytelling. So, to start off, you have a wide range of works now, from Order of Tales, The Island Book series, things like The Harrowing of Hell, and the illustration series you did for Moby Dick and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Can you talk a little bit about the motivations for these different kinds of works you've pursued?

Evan Dahm: Yes, do you mind if I turn my camera off because I think my computer gets overloaded.

James Lee: Okay that's fine no worries.

Evan Dahm: Basically, I just latch onto something and get obsessed with it. A lot of those projects, I did concurrent with Vattu which I've been working on since 2010 so a lot of it is trying to judge how much I can do it once. I feel like I've gotten a little better at understanding the sort of work, the sort of interest, that I have in a project that will actually propel me through it in a way that is not too grueling.

There's the money thing, like if a publisher is interested in working with me and I have something that I can make work with them. Then at certain points I'm kind of obliged to go through that but I'll just latch on to some idea and sometimes it'll stick in my head for a couple years until it can materially happen.

The Harrowing of Hell book with Iron Circus was an idea that I had probably two or three years before I actually started working and actually signed the contract on it. It seemed like an interesting way to work through Christian anarchism. And it occurred to me years and years ago that with books that are in the public domain, you can just do whatever you want with them so I had this rolling idea in my head of “Oh, I should think about what old book I like that'll be fun to draw.”

James Lee: I got my copy right here.

Evan Dahm: Oh yeah.

James Lee: That's interesting. The public domain stuff. Those are good points you raised in terms of having the freedom to explore with these things that are in the public domain. With that line of thought, what do you think about Disney's dominance of in this field of copyright?

Evan Dahm: I think Disney is the enemy basically. I'm very interested in old animation, and this is the thing I just learned. Back when full color film printing was being developed there was this window of a few years where it was not technologically possible to do full color film animation, but Disney had the exclusive rights to use that technology for five years or something in the 30s. So, there's this window of time where the only color cartoons coming out in America were from Disney. I don't know, it's just a horrible anti-art thing to do to close off this technology from the whole rest of the world, what was this obviously booming and exciting new medium.

But yeah, they've always been doing that. Their main project is to, in the way that capitalism delineates and commodifies all physical space available to it, the project of I guess any corporation like Disney is going to be to expand and commodify all the intellectual property space. Bleed dry the theoretical fictional universes of Star Wars or whatever and just extend copyrights so that they can maintain control of their stupid little mouse cartoon that nobody who worked on it is even alive.

James Lee: Recently I saw that Winnie the Pooh finally entered public domain. That was a bit of big news at the moment.

Evan Dahm: The book at least. It's the same deal with The Wizard of Oz where derivative works can refer to the book but not to the adaptation because the adaptation is still under copyright.

James Lee: Little nuances in that which can complicate the picture.

Evan Dahm: Pretty cool though. I love the public domain.

James Lee: There's lots of great ideas there and why not explore some of these things in a different way as well.

James Lee: I want to get back to the corporate stuff because I think it'll tie into the current issues and trends but let me ask a little bit more about your approach to world building and storytelling.

You started Rice Boy with improvisation with those first few pages, which had a dreamy quality to them, and by the end of it there was this very big sprawling history of a world in which you set subsequent stories, such as Order of Tales and Vattu. So with that said, how do you manage this tension between planning things out and letting things flow more freely, specifically the big picture stuff and the small steps need to take to get there?

Evan Dahm: I’m trying to think about that lately, because I have approached that in different ways for everything. I can identify in retrospect that that my working solution to that problem was to have a big clear template for the story that I could always refer to, and I could improvise, but it was always in connection to that template. Rice Boy in particular was very, not totally, pretty significantly improv but it's such a clear and straightforward riff or parody on the normal epic quest, the hero's journey thing, that I had that to hold on to as I was meandering around. Order of Tales was planned very, very tightly so that's a different question, I think.

Vattu has ended up having a lot of sort of improv space within it, and it hasn't been modeled on a clear template story. But what has ended up happening is that I've just had a very clear sense of like a few guiding principles for Vattu like the thematic arguments of it, the trajectories of the central characters, and the physical space of the story takes place in. That being like extremely consistent is a helpful thing, I think, to keep it all sort of tied together.

James Lee: Yeah.

Evan Dahm: Go ahead sorry.

James Lee: I was going to mention how, in your documentary you had gone through some of this in terms of how you actually used modeling software to craft the location and use that as a frame of reference, which I thought was a very interesting and detailed approach to world building.

Evan Dahm: Thank you, it was very fun obsessive little project. And the main thing is that it yields something that feels pretty consistent throughout the book, which is I imagine generally pretty difficult to do in something that takes that long to make.

But I am really trying to think about this improvisation versus planning thing lately because I'm reading a lot of manga and comics that are a little more comfortable wearing on their sleeve the fact that they've been originally serialized and sort of improvised. I love that and it feels so true to the nature of how comics are generally made unpublished. There's some disservice being done to the medium I think when we when we impose the standards of a perfectly planned out and self-contained novel on it so I'm trying to think about that in regards to how I'm approaching the next stuff I'm doing.

James Lee: Maybe we can think of the whole Marvel Cinematic Universe interconnected world approach here. I want to get to a point you raised about world building as well in your documentary. Basically, the argument you made was that, at the end of the day, the setting, the world that you craft, all these things must work in service to the story. And building on that, you also note that the characters in these worlds don't have their whole cosmology defined, let alone understood. Could you speak a little more about what informed this approach and maybe challenges with this, especially when you navigate these tensions between improv and structure?

Evan Dahm: I don't mean it to be as dogmatic as it probably sounds in that this is just my approach and I'm prioritizing certain things. It is important to keep in mind that you're not making an objective thing and that a lot of the premises of world building in the secondary world fantasy traditions that I’m into are on the premise that you're observing a story objectively – you're observing a world objectively and being described totally objectively to you. I don't think such a thing is possible in the same way that pure objective journalism is a kind of politically regressive impossible idea, I think.

You're always making some sort of statement, so I think it's important to keep in mind that it can be a productive tool to build in this sense of a consistent world, but you can really get sort of stuck, I think, because the thing will never be detailed or objective seeming enough. And you can go in the direction of nailing down all those little details but for what? I'm doing this stuff because I like stories and I like drawing basically. If the literary tool of an invented setting, which is a tool that I love and I like how it works, if that tool is not conducive to the story, then I'm just going to break it. Why not?

I've been interested in the world building thing and part of why I'm interested in it is because that's been consistently the biggest single thing that people want to talk to me about in my work. It always comes up in relation to my work, I guess, because my stuff is so visually, at least, totally invented-seeming.

I'm interested in it and I'm interested in how it's talked about. I look at a lot of media about how to do it, how to world build, and it just doesn't… This idea that you can objectively build a real believable world, that you can like have a strong feeling of escapism into it, just feels like a dead end to me and it feels ideologically and creatively limiting. Yeah, I got a little abstract there but that's basically what I think.

James Lee: I think it really ties into the corporate approach to world building. You have the Star Wars films and then they make a reference to a planet which is their theme park in one of their cities which you can go to experience another facet of this, which you know goes on and on. Basically, it’s a very ruthlessly cynical way of approaching world building perhaps.

Evan Dahm: Absolutely but it's interesting too. It's fun and interesting to see all the detail worked out or whatever. But I think that's exactly the comparison, I think Star Wars is the best possible example to talk about with that stuff I was thinking about. There's a useful parable for this – you have all these weird random background characters in the first Star Wars movie in 1977 that were mostly reused costumes from other movies, or whatever they had on hand in that cantina scene. But then, after the movie came out and George Lucas was leveraging, trying to do this really unprecedented thing with merchandising and making little action figures every single character, all those characters have to be named because now they're action figures. That's the exact same logic by which every single detail that serves a story begins to seem to demand expansion into further elaborated media product. I haven't watched any of the new Disney stuff, but it seems like filling in all the little gaps or whatever. Maybe the shows are good, but the approach is just so as cynical, as you say yes.

James Lee: Yeah, I don't want to downplay the love and effort that goes into these productions, and also the people who enjoy them and then subsequently are inspired by them. But you can't help but feel a little bit of ambivalence towards them as well.

Evan Dahm: Yeah, and you don't want to be rude to people for liking a thing that's utterly dominant in pop culture, but it is utterly dominant so there's no foul in giving the product shit, I don't think.

James Lee: Yes, we can think of it as some healthy critique.

Evan Dahm: Sure, yes.

James Lee: I think Star Wars is a good example to talk about this next question here. So, in recent times, or actually maybe it's been going on much longer, there seems to be a tendency among audiences to rigidly equate media consumption with political activism and morality. That what you watch on screen will inform their moral compass. And likewise, they feel that these works and the people who make them must reflect righteous view of the world or what have you. Could you give your impressions on this idea that stories can be used as a way to inform or explore real world issues and maybe some of the twists and turns that has taken?

Evan Dahm: Yeah man that's a huge part of the discourse I think that's been a pretty striking increase over my adulthood over the course of my being aware of it and it's coincided with a general increase in political literacy, which in myself and in you know other people of my generation, or whatever, which is good. But it's an interesting problem because I think that culturally – generally – we're better equipped to, as creators and readers, think about what work is saying politically. But we're doing that within a world where we are increasingly politically disempowered lately. I feel like we default towards a really legislative or punitive way of looking at this stuff. So, we can look at and we can pick apart the initially invisible political premises of a certain work. But if our conclusion is to say that this work is bad and if you like anything about it then you're bad that's against the spirit of the critical apparatus that brought us there in the first place, I think.

And it's silly. I don't engage with a lot of it publicly, but it is silly watching all this culture war stuff where people are trying to make supporting this or that media a political act when it's all just Disney stuff. They don't care about you. There is probably some good happening when works of fiction make a liberatory argument or represent people and ways of life that aren't habitually represented. But it just feels like we're just otherwise disempowered so we're fixating on what's happening in pop culture.

James Lee: To be honest, this was my pet theory too. That people feel they lack control in real world politics and situations so these fantasy worlds that they find comfort in become their way of asserting control and also thinking through these issues.

Evan Dahm: Yeah. All this talking around the abortion thing this last day, the ways that the mainstream of the culture has to think about political agency are very, very limited. People will talk about “you have to vote.” And I voted. We voted. Democrats have an enormous amount of power. So, what else? I feel like we don't have a lot of political imagination and we can't even really understand the world, or at least the mainstream of the culture in America can’t really understand what political power is or how to exert pressure or something. I'm part of that. I'm a defeatist about all this stuff too a lot but… I imagine I made that connection a little better.

James Lee: It's complicated to navigate these issues and be working in let's say crafting stories, making fiction, and comics, media, entertainment.

There is an interesting case to get at some of these complexities – the Harry Potter series.

Famously there was youthful activism around the series, the Harry Potter Alliance from a while ago and the premise of this organization was put into action the kind of spirit of the characters in the real world.

Evan Dahm: I'm familiar with this.

James Lee: Yes, so you probably know that they made some headway on some issues like Fair Trade chocolate things like this, other social issues, but as most of us are familiar with the author of the series, J.K. Rowling, has expressed a lot of negative views about certain communities, which has resulted in tensions in terms of how do you draw inspiration from a work made by someone who does not necessarily share the viewpoints or support of the audience. And the organization rebranded a couple years afterwards, kind of to distance themselves. But I think it's a good case to think about how fiction can be used as a vehicle to motivate people but also it is wrapped around in these issues of does it reflect on the author? Can the audience just run with it in their own way?

Evan Dahm: Yeah, that's interesting. I like stories that are by one person. There was part of it that was exciting to me to see Rowling wrote these books herself and they're her thing. I was exactly the age to be into them when they were coming out. It's just wild to see something that is all about one person's project become this huge global media thing, and it wasn't some created-by-committee intellectual property. What are you going to do? She's so just out there and despicable but I don't know how to engage with any of that.

James Lee: She's not making it easy to keep liking the books.

Evan Dahm: Yeah.

James Lee: But people try to separate the two.

Evan Dahm: Since I read those as a kid I've gotten deeper into the sorts of fantasy writing that I feel like those books are a pale imitation of. So there's that too, but even if the books were could be great and she would still be who she is. Yeah, I don't know, what's the question there exactly?

James Lee: I think the original question was about using stories as a way to inform real world issues. Oh, and something else that I've read is that oftentimes people they don't necessarily just consume media in one direction. Sometimes the media itself is a vehicle for them to express certain things which means that what the author is saying matters less than what they want to express through however they critique or consume it.

Evan Dahm: You mean in a fandom sort of sense?

James Lee: Yes, in a fandom sort of sense, where they see something and interpret it or use it for their own purposes.

Evan Dahm: Yeah, that generally seems cool to me. I've never been in that sort of world and I've never really understood the impulse. But generally, I like seeing people take ownership of this stuff that’s so aggressively owned by somebody else.

James Lee: Yeah, I mean I think there's kind of a thread here in terms of also copyright and ownership to in terms of when we think about fan output, like fanfiction or other kind of fan productions in terms of what are the fans free to do with this work. Can they do something more interesting or something more valuable for themselves with it? But the law lays its heavy hand at times and shuts down somebody’s fan production.

Evan Dahm: Yeah and then in some circumstances, the creator is incentivized to shut it down so that they can be shown to be defending their ownership of a thing or something. It has not really come up as a thing for me to think very much about, I guess.

James Lee: Yeah well, I suppose maybe if we can make the Overside extended universe a thing perhaps this will come up.

Evan Dahm: I don't see why they wouldn't be fine and cool with me.

James Lee: Yeah, I guess there are some legal issues, especially with fanfiction if companies choose to pursue them. I think most people just fly under the radar which I think is fine.

James Lee is a graduate of the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. He likes comics, art, and popular culture related topics.