Sites of Convergence: An Interview for Brazillian Academics

/Vinicius Navarro has published an extensive interview with me in the current issue of Contracampo, a journal from Universidade Federal Fluminense (Brazil). Navarro and his editors have graciously allowed me to reprint an English version of the interview here on my blog. Done more than a year ago, Navarro covered a broad territory including ideas about convergence, collective intelligence, new media literacies, globalization, copyright, and transmedia storytelling. Sites of Convergence: An Interview with Henry Jenkins

by Vinicius Navarro

Media convergence is not just a technological process; it is primarily a cultural phenomenon that involves new forms of exchange between producers and users of media content. This is one of the underlying arguments in Henry Jenkins's Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, a provocative study of how information travels through different media platforms and how we make sense of media content. Convergence, according to Jenkins, takes place "within the brains" of the consumers and "through their social interactions with others." Just as information flows through different media channels, so do our lives, work, fantasies, relationships, and so on. In Convergence Culture, Jenkins explores these ideas in discussions that include the TV shows Survivor and American Idol, The Matrix franchise, fans of Harry Potter and Star Wars, as well as the 2004 American presidential campaign.

Henry Jenkins is one of the most influential contemporary media scholars. In addition to his book on media convergence, he is known for his work on Hollywood comedy, computer games, and fan communities. More broadly, Jenkins is an enthusiast of what he calls participatory culture. Contemporary media users, he argues, challenge the notion that we are passive consumers of media content or mere recipients of messages generated by the communications industry. Instead, these consumers are creative agents who help define how media content is used and, in some cases, help shape the content itself. Media convergence has expanded the possibility of participation because it allows greater access to the production and circulation of culture.

In this interview, Jenkins speaks generously about the promises and challenges of the current media environment and discusses the ways convergence is changing our lives. As usual, he celebrates the potential for consumer participation, but he also notes that our access to technology is uneven. And he calls for a more inclusive and diverse use of new media. One of the places in which these discrepancies are apparent is the classroom. Jenkins believes that we need new educational models that involve "a much more collaborative atmosphere" between teachers and students. He also argues that we must change our academic curricula to fit the interdisciplinary needs of our convergence culture.

These are some of the questions we must confront in the new media environment of the twenty-first century, an environment in which consumer creativity clashes with intellectual property laws, Ukrainian TV shows find their way into American homes via YouTube, and transmedia narratives reshape the way we think about filmmaking.

In Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, you oppose "the digital revolution paradigm" - the idea that new media are "going to change everything" - to the notion of media convergence. You also say that "convergence is an old concept taking on new meanings." What exactly is new about the current convergence paradigm? And what changes may we expect from the convergence (or collision) of old and new media?

The idea of the digital revolution was that new media would displace and, in some ways, replace mass media. There were predictions of the withering away of broadcasting, just as earlier generations of revolutionaries liked to imagine the withering away of the state. That's not what has happened. We are seeing greater and greater interactions between old and new media. In certain cases, this has made new media more powerful rather than less. The power of the broadcast networks now co-exists with the power of the social networks. In some ways, this has pushed broadcasters to go where the consumers are, trying to satisfy a widespread demand for the media we want, when we want it, where we want it, demand for the ability to actively participate in shaping the production and circulation of media content. This is the heart of what I mean by convergence culture. The old notion of convergence was primarily technological - having to do with which black box the media would flow through. The new conception is cultural - having to do with the coordination of media content across a range of different media platforms.

We certainly are moving towards technological convergence - and the iPhone can be seen as an example of how far we've come since I wrote the book - but we are already living in an era of cultural convergence. This convergence potentially has an impact on aesthetics (through grassroots expression and transmedia storytelling), knowledge and education (through collective intelligence and new media literacy), politics (through new forms of public participation), and economics (through the web 2.0 business model).

What's new? On the one hand, the flow of media content across media platforms and, on the other, the capacity of the public to deploy social networks to connect to each other in new ways, to actively shape the circulation of media content, to publicly challenge the interests of mass media producers. Convergence culture is both consolidating the power of media producers and consolidating the power of media consumers. But what is really interesting is how they come together - the ways consumers are developing skills at both filtering through and engaging more fully with that dispersed media content and the ways that the media producers are having to bow before the increased autonomy and collective knowledge of their consumers.

The concept of "convergence" brings to mind the related notions of co-existence, connection and, in some ways, community. In this culture of convergence, however, we continue to see a divide - social as well as generational - between those who participate in it and those who don't. What can we do to narrow this gap and expand the promise of participation?

This is a serious problem that is being felt in countries around the world. Our access to the technology is uneven - this is what we mean by the digital divide. But there is also uneven access to the skills and knowledge required to meaningfully participate in this emerging culture - this is what we mean by the participation gap. As more and more functions of our lives move into the online world or get conducted through mobile communications, those who lack access to the technologies and to the social and cultural capital needed to use them meaningfully are being excluded from full participation.

What excites me about what I am calling participatory culture is that it has the potential to diversify the content of our culture and democratize access to the channels of communication. We are certainly seeing examples of oppositional groups in countries around the world start to route around governmental censorship; we are seeing a rise of independent media producers - from indie game designers to web comics producers - who are finding a public for their work and thus expanding the creative potential of our society.

What worries me the most about participatory culture is that we are seeing such uneven opportunities to participate, that some spaces - the comments section on YouTube for example - are incredibly hostile to real diversity, that our educational institutions are locking out the channels of participatory media rather than integrating them fully into their practices, and that companies are often using intellectual property law to shut down the public's desire to more fully engage with the contents of our culture.

One place where the divide manifests itself very clearly is the classroom. In an interview for a recent documentary called Digital Nation (PBS), you said: "Right now, the teachers have one set of skills; the students have a different set of skills. And what they have to do is learn from each other how to develop strategies for processing information, constructing knowledge, sharing insights with each other." What specific strategies do you have in mind? What educational model are you thinking about?

Last year, I had the students in my New Media Literacies class at USC do interviews with young people about their experiences with digital media. Because my students are global, this gave us some interesting snapshots of "normal" teens from many parts of the world - from India to Bulgaria to Lapland. In almost all cases, the young people enjoyed a much richer life online than they did at school; most found schools deadening and many of the brightest students were considering dropping out because they saw the teachers as hopelessly out of touch with the world they were living in.

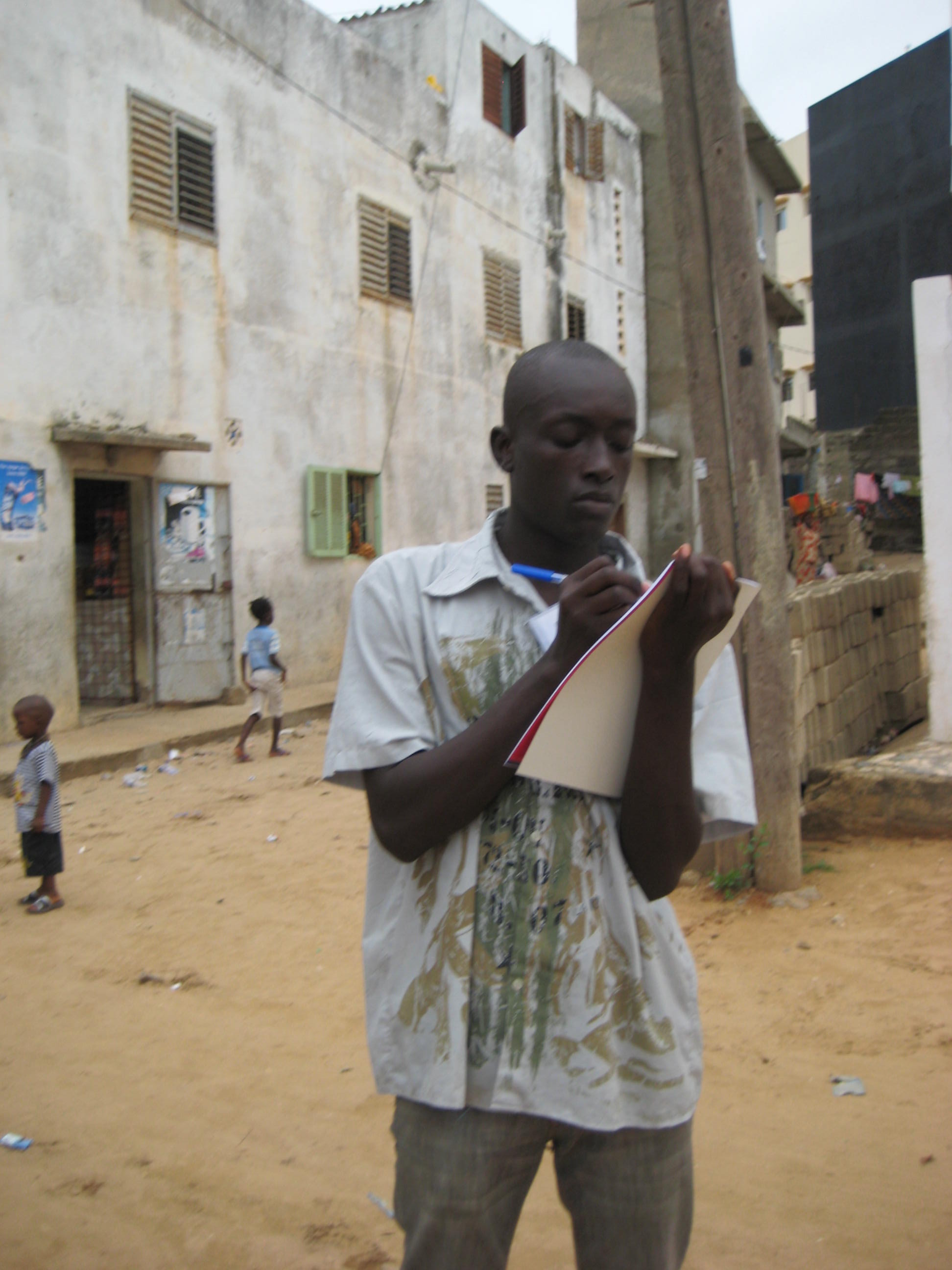

Yet, on the other side of the coin, there are young people who lack any exposure to the core practices of the digital age, who depend upon schools to give them exposure to the core skills they need to be fully engaged with the new media landscape. And our schools, in countries all over the world, betray them, often by blocking access to social networks, blogging tools, YouTube, Wikipedia, and so many other key spaces where the new participatory culture is forming.

Over the past few years, I've been involved in a large-scale initiative launched by the MacArthur Foundation to explore digital media and learning. I wrote a white paper for the MacArthur Foundation, which identifies core social skills and cultural competencies required for participatory culture and then launched Project New Media Literacies to help translate those insights into resources for educators. The work we are doing through Project New Media Literacies (which was originally launched at MIT but which has traveled with me to USC) is trying to experiment with the ways we can integrate participatory modes of learning, common outside of school, with the core content which we see valuable within our educational institutions.

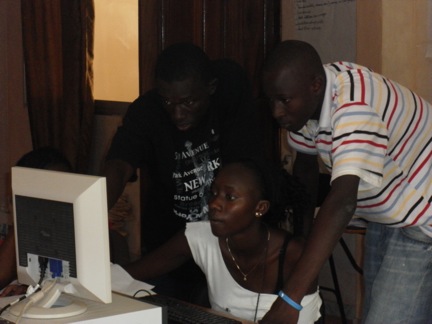

For us, teaching the new media literacies involves more than simply teaching kids how to use or even to program digital technologies. The new media landscape has as much to do with new social structures and cultural practices as it has to do with new tools and technologies. And as a consequence, we can teach new mindsets, new dispositions, even in the absence of rich technological environments. It is about helping young people to acquire the habits of mind required to fully engage within a networked public, to collaborate in a complex and diverse knowledge community, and to express themselves in a much more participatory culture. This new mode of learning requires teachers to embrace a much more collaborative atmosphere in their classrooms, allowing students to develop and assert distinctive expertise as they pool their knowledge to work through complex problems together.

Vinicius Navarro is assistant professor of film studies at the Georgia Institute of Technology. He is the co-author (with Louise Spence) of Crafting Truth: Documentary Form and Meaning (Rutgers University Press, 2011). He is currently working on a book on performance, documentary, and new media.