By Any Media Necessary (Part Two): Conversation Starters on Digital Voice (By Any Media)

/This is the second in a series of posts showcasing the archive and resources we have assembled around our book project, By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism, which is being released by the New York University Press. This book was funded by the MacArthur Foundation's Youth and Participatory Politics Network and written by Henry Jenkins, Sangita Shresthova, Liana Gamber-Thompson, Neta Kligler-Vilenchik, and Arely Zimmerman. resources curated by: Alexandra Margolin, Gabriel Peters-Lazaro, Sangita Shresthova

The “Conversation Starters on Digital Voice” collection aims to help you get a conversation on By Any Media Necessary started in communities, organizations and educational settings. The core theme shared by all the conversation starter short films in the series is that the nature of political participation is changing in an era of networked communication. More and more we rely on each other for news and information, more and more we work through issues and concerns in conversation with others within our social networks, and more and more we tap the affordances of new media in order to mobilize for change.

As we do so, then, there are practical and ethical challenges: Young people -- indeed, all of us -- need to take responsibility for the quality of information they circulate, they need to recognize the risks and opportunities of political engagement, they need to understand the copyright implications of their choices to remix and share media, and they need to respect the contributions of others within their community. We want to use these interstitials to help young people to better understand what is at stake in participatory politics and to ask core questions before they act online.

How were these films and materials created? All the interstitial films were created through collaboration between MAPP, Pivot.tv and Joseph Gordon Levitt's HitRECord. Below is a little more information about each of the collaborators.

HitRECord The collaboration started with HitRECord, a self-described “professional open collaborative production company” founded by Joseph Gordon-Levitt. According to Gordon-Levitt:

HITRECORD is different than your typical Hollywood production company. Anyone with the Internet can contribute to our collaborative projects & this website is where we come to make things together, like Short Films, Books, Music, Art, and our latest & greatest production - our television show: HITRECORD ON TV. You can contribute your Video, Image, Text, or Audio RECords to any of the collaborations we're working on, or you can start your own collaboration on the site. And if your work gets used in a money-making production, we pay you for it. For their work in 2013, the community is receiving a grand total of $737,175.09.

HITRECORD ON TV airs on the Pivot.tv television network which is a component of Participant Media.

Participant Media/Pivot.tv

Participant Media is a media company that serves a double line “dedicated to entertainment that inspires and compels social change.” According to their website:

Founded in 2004 by Jeff Skoll, Participant combines the power of a good story well told with opportunities for viewers to get involved. Participant's more than 65 films include Lincoln, Contagion, The Help, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, Food, Inc., Waiting For "Superman," CITIZENFOUR and An Inconvenient Truth. Participant has also launched more than a dozen original series, including “Please Like Me,” “Hit Record On TV with Joseph Gordon-Levitt,” and “Fortitude,” for its television network, Pivot.

Pivot.tv is Participant’s television network where Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s HitRECord is aired. In their own words:

We're Pivot TV, a new TV network where what you watch does make a difference. We've got all the usual stuff like original shows, movies and docs, but we've also got a little something more. When you watch Pivot TV, you won't just be entertained. You can also take action on the issues raised in our content. The chance to do something about it will be right there on the screen, or just inside the next commercial break. So go ahead and pivot. You just might be able to make a meaningful difference in the world. Pivot TV: It's Your Turn.

Media, Activism and Participatory Politics (MAPP) The Media, Activism and Participatory Politics (MAPP) research team is lead by Henry Jenkins and is based at the University of Southern California (USC). Over the past five years, MAPP conducted five case studies of diverse youth-driven communities that translate mechanisms of participatory culture into civic engagement and political participation.

Building on these findings, the MAPP team partnered with the Media Arts + Practice Division at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts to create resources, conversation starters and workshops that encourage participants to think critically about previous examples of civic media and act creatively as they draw on their own experiences and aspirations to translate these insights into their own media practice. These resources and workshops currently live in the “By Any Media Necessary” collection and can be accessed at byanymedia.org.

What does this collection contain?

This collection contains the following:

Films: Four short conversation-starter films created through a partnership between HitRecord, Pivot and the Media, Activism and Participatory Politics (MAPP) Project at USC. The films cover the following digital age topics: credibility, private vs. public, remix and shifting the agenda

Resource Packets: Four corresponding resource packets with sample questions, key points, key term definitions, and examples that will help you identify ways that these films may serve your community or students

Supplemental Resources: Additional article resources on related topics to help you further explore the topics covered.

Conversation Starter Topic: Credibility in the Digital Age

How do we assess the quality of information we encounter online? What accountability and responsibility should we have over the integrity of the social justice content we decide to circulate? And how prepared should we be to defend the claims we make to support our arguments around political issues? According to a recent survey conducted by the MacArthur Foundation’s Youth and Participatory Politics Network, 85 percent of high school aged youth want more help in learning to discern the credibility of the information they encounter online. For us, this issue is most powerfully raised by our case study of Invisible Children’s Kony2012campaign, but it is also one which almost every public awareness effort confronts sooner or later.

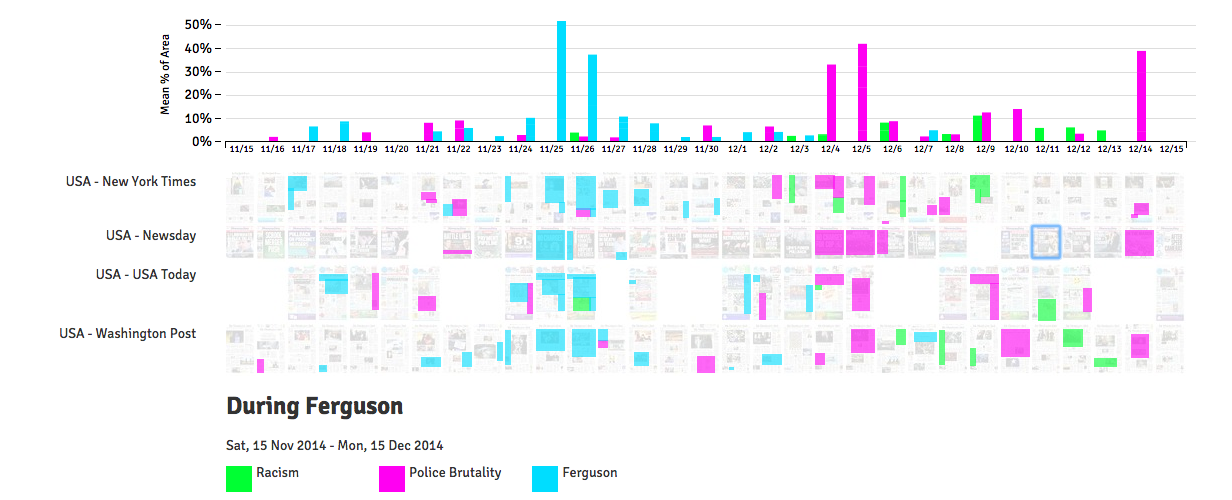

Conversation Starter Topic: Shifting the Agenda in the Digital Age How might identity groups use media to react to, reshape, or even control the narrative being constructed about them in mainstream media? We are seeing many of the groups we study -- but especially the DREAM activists and the American Muslim networks respond quickly to news stories or popular culture programming that they feel places them in a negative light. They are using their collective capacities to pull together information, critique representation, construct alternative narratives, and get them into circulation, often in ways that commands the attention of major news organizations. In part, these strategies work because of the ways they are able to quickly mobilize dispersed and decentralized networks that are invested in helping them spread content.

Conversation Starter Topic: Public vs. Private in the Digital Age

How might activists assess risks, especially those concerning privacy and security, as they share their stories online? In a widely shared critique of so-called “Twitter Revolutions,” The New Yorker’s Malcolm Gladwell argues that online activists do not face the same kinds of risks as previous generations faced in their struggles for civil rights. Yet, we are finding that there are high risks for, say, undocumented who post videos coming out via YouTube or American Muslim youth who use social media to think through their identities in the Post-9/11 era. Many of these risks emerge as these youth make choices about the bounds between publicity (“coming out,” “speaking out”) and privacy, which are similar to more mundane choices confronting all youth in the era of Twitter and Facebook.

Conversation Starter Topic: Remix in the Digital Age

How can appropriating and remixing content from popular culture lead to new kinds of political consciousness? And, how do activists who appropriate and remix existing media in their campaigns resolve issues around copyright? These are the sorts of topics that prompted the Remix conversation starter video collaboration with HitRECord.

We are seeing examples of the merging of the identities of fans and citizens across a range of political movements -- most spectacularly in our work through the Harry Potter Alliance and the Nerdfighters, but also in the use of remix for political expression via the Occupy Wall Street movement (like the Pepper Spray Cop memes), the protests against Gov. Walker in Wisconsin, “Binders Full of Women” during the 2012 Presidential Campaign, and the use of the Guy Fawkes mask, most closely associated in the United States with V for Vendetta, by a range of activist groups, including Anonymous.

Remix promotes a mode of political speech that can be easy to understand, funny and powerful. It contrasts with the policy wonk language that often excludes youth from meaningful participation. Within this context, copyright can be seen as “private censorship” that silences a particular kind of expression. Creative activists need to understand the basic criteria of Fair Use and make informed choices as they quote and circulate pre-existing media. Diving into these complex issues with your organization, community or students can open up many opportunities for meaningful learning. In classroom contexts especially, remix practices may intersect with questions around plagiarism and present a productive context in which to develop best practices for citation and appropriate use of existing content for purposes of critique and transformative work. This video is meant to be a starting place and jumping off point. More context, resources, and topics to consider are provided below.

You can also download "Conversations on Digital Voice" resources and videos here.

-------

Alexandra Margolin is the Project Manager for the Mellon Funded Digital Humanities Initiative at the Claremont Colleges. She comes from a background in Ethnic Studies, non-profit project management, and grassroots media production having spent the last 6 years working on non-profit and higher education grants. Prior to joining Claremont's Digital Humanities team, Alex served as the Program Specialist for the Media Activism & Participatory Politics (MAPP) project at USC which examined participatory models of youth activism and was responsible for the project's outward facing programming with activists and educators. She received her B.A. in history from Pitzer College and an M.A. in Asian American Studies from UCLA. Her research interests include: social constructions of multiraciality through foodways, social justice learning, and alternative modes of storytelling.

Gabriel Peters-Lazaro is an assistant professor of the practice of cinematic arts in the Division of Media Arts + Practice at the USC School of Cinematic Arts where he researches, designs and produces digital media for innovative learning. As a member of the Media, Activism and Participatory Politics (MAPP) project he works to develop participatory media resources and curricula to support new forms of civic education and engagement for young people. He helped create The Junior AV Club, a participatory action research project exploring mindful media making and sharing as powerful practices of early childhood learning. He teaches graduate and undergraduate courses on digital media tools and tactics, digital studies and new media for social change. He received his B.A. in Film Studies from UC Berkeley, completed his M.F.A in Film Directing and Production at UCLA and is a Ph.D. candidate in Media Arts + Practice.

Sangita Shresthova is the Director of the MacArthur funded Henry Jenkins’ Media, Activism & Participatory Politics (MAPP) project based at the University of Southern California. MAPP focuses on civic participation in the digital age and includes research, educator outreach, and partnerships with community groups and media organizations, and companies. Sangita’s own scholarly work focuses on the intersections among popular culture, performance, new media, politics, and globalization. She holds a Ph.D. from UCLA’s Department of World Arts and Cultures and MSc. degrees from MIT and LSE. Her book on Bollywood dance and globalization (Is It All About Hips?) was published by SAGE Publications in 2011. Drawing on her background in Indian dance and new media, she is also the founder of Bollynatyam’s Global Bollywood Dance Project. Her more recent research has focused on issues of storytelling and surveillance among American Muslim youth and the achievements and challenges faced by Invisible Children pre-and-post Kony2012. She is also one of the authors on By Any Media Necessary: The New Activism of Youth, a forthcoming book that will be published by NYU Press.