Reading Hellboy: An Interview with Scott Bukatman (Part One)

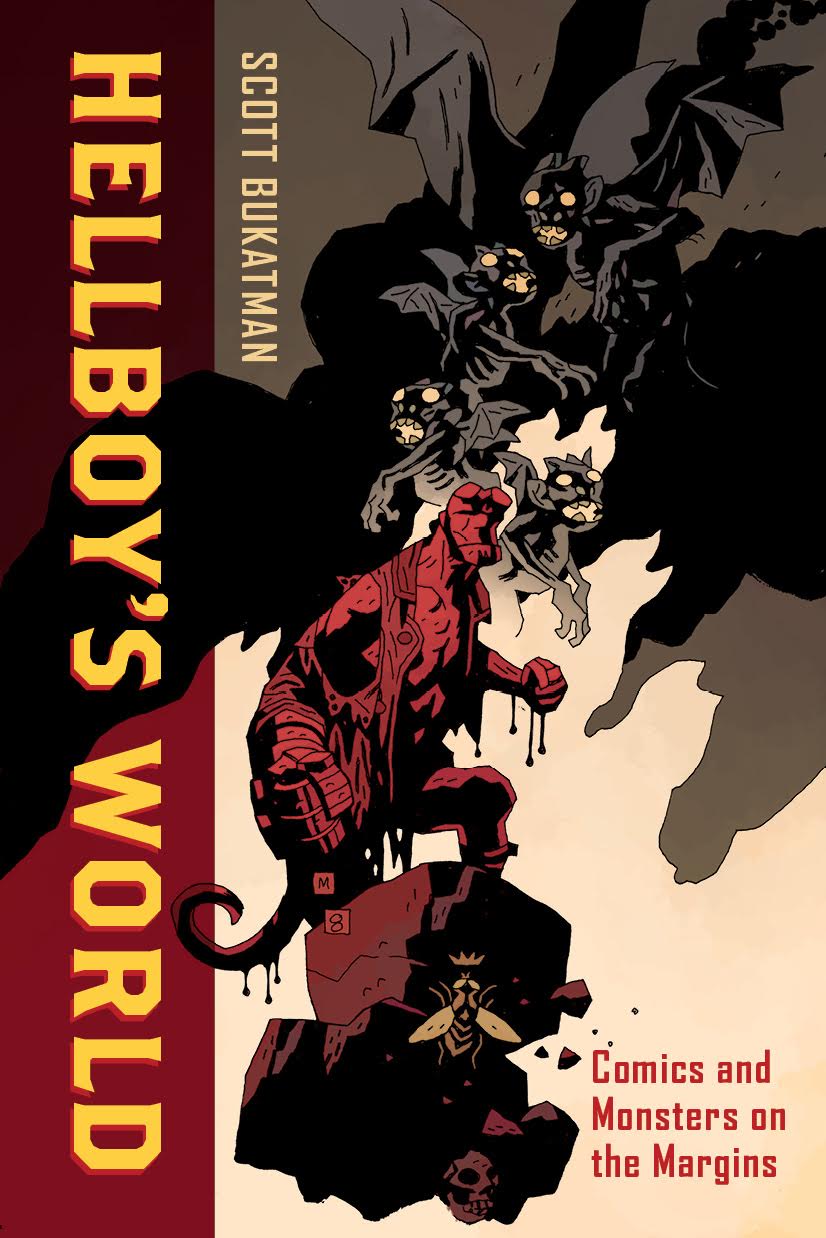

/I've been watching Scott Bukatman grow as a scholar for several decades now -- from his first writings about science fiction film, television, and literature (Terminal Identity) through his early writing about Superheroes and comics (Matters of Gravity) to his explorations of early comics and animation (The Poetics of Slumberland). I've long admired him as a scholar who can write about a broad range of media genres and practices, as an art historian who moves across high and low, as an original voice who brings a fresh and compelling perspective to everything he writes about, and as someone whose work is consistently witty and fun to read. So, I came into his newest book, Hellboy's World: Comics and Other Monsters on the Margins, with high expectations, but page by page, he surpassed them.

We've long been traveling along parallel paths -- representing different roots (he combines the formal with the phenomenological, I combine the formal with cultural studies, at least when we are both writing about the popular arts), but I learned something new on every page here, as he offers us a rich way into the comics of Mike Mignola, which among other things, thinks about the pleasures of reading words and pictures, the expressive use of color, the process of world-building, the relationship of comics to sculpture, and the expressive/emotive potential of color. All of which make this much more than a monograph about a single author and his work -- Hellboy's World is really a manifesto for a different kind of comics studies.

This two-part interview will give you only a taste of the riches that await you there.

Much as you describe yourself in the book’s opening, I am someone who has dabbled around the edges with Hellboy, reading some issues, but not figuring out how or why to dig deeper. You obviously like him well enough to write a book about Hellboy, so give me a rec. Why should we read him and why should we read a book about him?

Well, I had read some of the early stories, but never realized that a significant cosmology was unfolding in Hellboy and its later spin-off titles, BPRD in particular. I saw Hellboy as aesthetically lovely but narratively limited — I just couldn’t have been more wrong about that (I also hated Bowie when I was in high school. Unbelievable.)

The work is narratively complex, and in many ways it flies against the trends of the past few decades of superhero comics. Dialog is used sparingly so that the images and pages have room to breathe, characters’ backstories are presented briefly but affectingly, the Mignola-verse encompasses a satisfyingly coherent range of visual and narrative styles…

And as I dug into the beautiful, large-scale Library Editions of the Hellboy comics, I found more and more to think about and want to write about: Mignola’s aesthetic and approach to the page, the shared universe he and his collaborators were building, the intersection of Hellboy et al with other genres and worlds — all of these were compelling, but what really did the trick was looking at the Hellboy films and finding them so wanting. The Hellboy films helped me think about what comics were, and what were the specific pleasures about reading them. Mignola’s work came to epitomize comics for me.

You’ve been doing comic studies longer than most of us. How would you characterize the status of this field? What has it meant to you to be studying comics in the context of an art history department? Clearly it comes through when you write here about Rodin or Goya but…

I’m not so great at these “state of the field” questions, but I’m excited that comics studies has become an emergent field. There are still no comics studies jobs in the world, but more departments (like my own) are willing to entertain comics offerings with increasing regularity.

The field is still far too content-driven — many scholars come from lit departments, and all too often the words are taken to be the thing itself. I’m happier when folks remember that comics are words and images that exist in a complicated equilibrium. I also think there’s too much emphasis on identity politics, but that makes perfect sense when you look at graduate students and junior faculty who must demonstrate their seriousness of purpose while studying comics.

I often find a big disconnect between the ways younger scholars write about comics (critical distance!) and how they talk about them (fanboys/girls!) — I’d like to see that gap close, have scholars simply own their love of them comics.

As for working in an art department — I think I have become much more engaged with non-moving images after nearly two decades in an art department (I come from film studies), and enjoy engaging with them — it certainly allows me to privilege the aesthetic experiences that comics provide.

You begin the book by evoking Walter Benjamin and he hovers over your text as a key influence. So, what does Benjamin have to contribute to contemporary comics studies? To what degree does Benjamin inspire the persistent focus on the reader’s experience -- what you call “the adventure of reading” -- across your book?

Yes, my book begins with a long passage from Benjamin where he evokes the experience of a child reading, and it’s writing that just sings to me as a reader, a reader of comics, and a scholar. I’m forced to admit that, much as I love comics, it was cinema (which emerged at the same time that comics became a mass medium) that became the medium of the 20th century. Within a few decades of its invention, there was already an amazing literature exploring the implications of cinema’s particular mode of address, its place in the modern world, even its potential to epitomize the modern world.

Comics did not (and pretty much do not) generate the same kind of philosophical rumination. Cinema is more profound in its address to the body and to perception, its reshaping of our experience of space and time, and in its immersive hold.

So I decided to take another tack, to try to understand what special purchase reading comics could have upon us (or me, at least). We call people who engage with comics “readers,” and in this evolving transmedial landscape I’m really interested in what it is we do when we read comics. What makes it a unique experience? What was it about reading Hellboy that did not survive the transition to film?

And Benjamin’s early writings on book collecting, illustrated children’s books, color, and reading emerged for me as hugely relevant to the consuming pleasures of reading comics. Our engagement with comics constitutes a more intimate experience than with cinema, and it foregrounds the ways that we read. In many ways, it returns us to, and builds upon, our childhood experience of picture books, and to our early experience of books as precious objects in our lives and our imaginations.

So, where Stan Brakhage tried to recapture what he called the “adventure of perception” in his filmmaking, I’m suggesting that comics offer up an “adventure of reading.” Not all comics do this, nor do all readers. But it’s there, and it’s significant.