The Czech Zine Scene (Part 3): Feminism

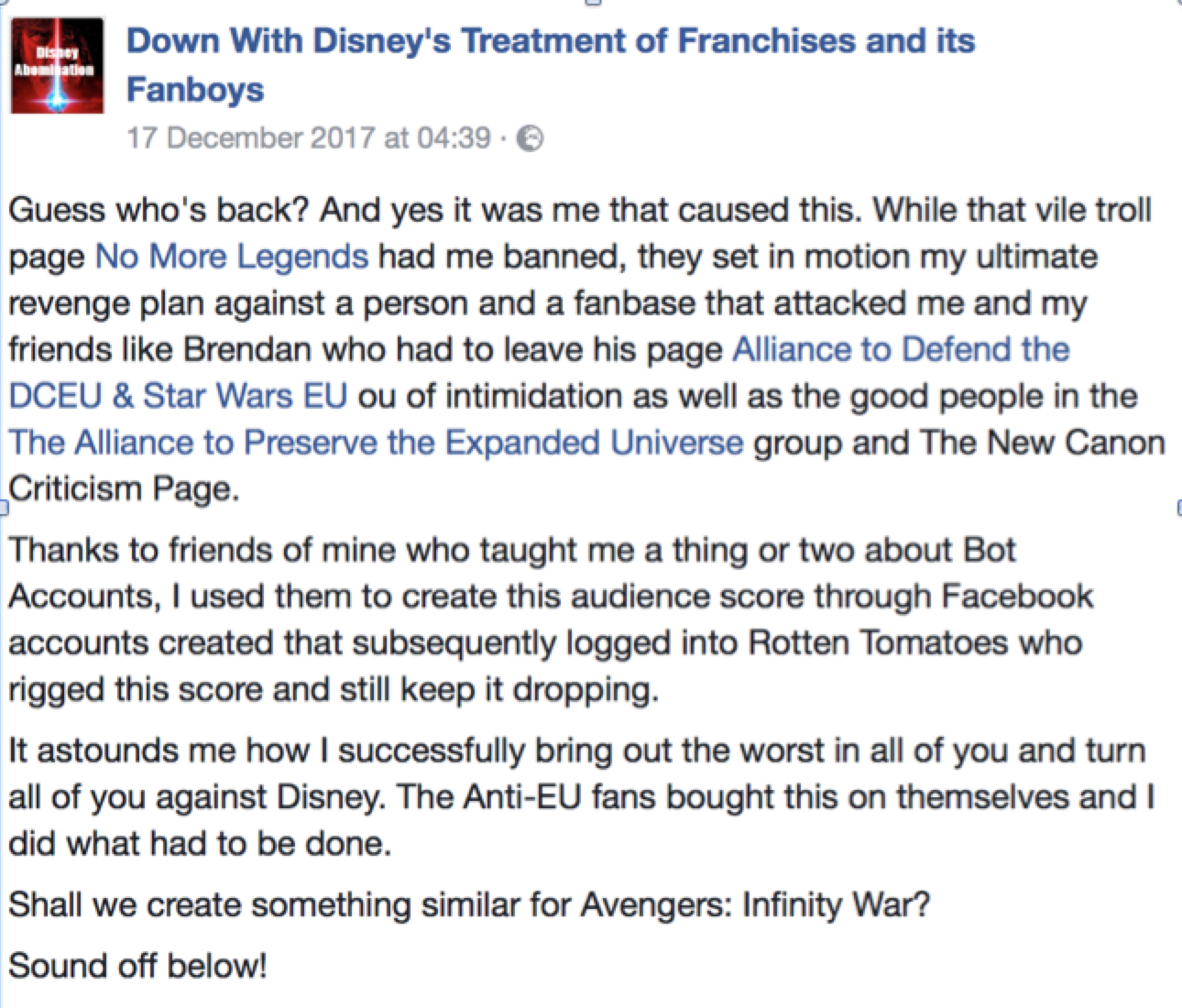

/Bloody Mary #!0 2005

Troublemaker Girls of the World, Unite!

By Jitka Kolářová

—

I was involved in publishing feminist fanzines for about ten to twelve years. Some might remember Femidom, a sexuality fanzine, or the radically queer Q_Kvér, but the longest running one was Bloody Mary. For me, it was the female space that I was lacking. This is actually a fundamental part of feminist zines. They're not only printed pieces of paper; they're a community, a network, a safe haven where you can be among similarly fired-up people. That is to say, it's for and by people who aren't afraid to speak about things you wouldn't hear about in the “neutral world”, nor in “neutral zines”. To this day, these things aren't talked about as much as they deserve to be.

That there are and were strong, creative, and inspirational women in the world; be it musicians, weightlifters, scientists, or revolutionaries. The oppression and prejudice that you face as a woman every day–harassment on the street, putting down of your abilities, expecting that it'll be you who washes up the dishes after the party while still looking sexy–these aren't OK, and they need to be changed.

For me, Bloody Mary was a means to vent frustration from everyday sexism. It was a channel in which I could forage for interesting female, feminist, and queer groups or activities and write about them. A friendly group of girls who spent time together far beyond the scope of fanzine production. A link with other people that we sent the zines to be distributed to, or who would play at fundraising gigs or would be connected internationally.

Sweethearts, Intellectuals, Punk Girls

When I asked musician, feminist, and pedagogue Pavla Jonssonová, who was de facto the person who brought me to writing fanzines, what was before Bloody Mary, she spoke of the underground magazine Vokno by Mirek Vodrážka, who, as a feminist, brought this particular theme into the magazine's scope. Apart from this, feminism was practically not discussed at all. There were women amongst dissidents, but they had more of an invisible service role, copying and distributing unofficial self-published documents and creating a supportive family environment for their dissident husbands. It wouldn't have worked without them, but their role and standing wasn't really considered–the exception being the 'Ženy v dissent' (Dissident women) project.

The topic of women's rights, gender, and feminism only began to be talked about after 1989 by writers and scientists such as Eva Hauserová, Carola Biedermannová, Saša Berková or Jiřina Šiklová. I dubbed this “First Wave of Feminist Writings” as “Intellectuals” for my own use–they weren't rebellious youngsters, but sought to engage in discussion and to establish a theoretical base. Thanks to Jiřina Šiklová, the Gender Studies library came into existence, which is the largest of its kind in Central Europe and continues to function to this day. There were also rock girls from the bands Dybbuk, Plyn and Zuby Nehty. According to singer Pavla Jonssonová, they were quite moderate: “They liked us. They called us Sweethearts from the Philosophical Faculty”.

This nascent feminism didn't really have very sharp teeth in those times, and respect for women's activities needed to be fought for. Then, in the Nineties, things started changing at breakneck speed as society newly opened to outside influences sought to soak up Western influences, be it cowboy capitalism or punk or activism. Together with them came squatting, demonstrations, fanzines, and new forms of feminism. It's important to note that our inspiration for Bloody Mary was never samizdat, or unofficial dissident literature. We'd heard about it, we may have seen some at some point in time, but we were mainly interested and influenced by other things–Czech and foreign punk zines, but mainly feminism of young girls inspired by anarchism and DIY ethics, a movement which in the early Nineties spread quickly throughout the world and which called itself riot grrrls.

This girl movement originated in the early Nineties in the rock and punk scene in and around Olympia and Seattle in the United States. It fought against sexism, harassment, sexual violence, and incest, which were topics that feminism of the participants' mothers didn't really touch upon (they wanted to have a “career and family at the same time).” The standing of young girls, let alone their roles in some punk genres, wasn't talked about. The movement arose around bands such as Bikini Kill, Babes in Toyland, or Sleater Kinney and fanzines Riot Grrrl or Girl Germs. Apart from criticising conservatism, sexism, and capitalism, the movement devoted itself mostly to its own activities.

Girls started bands and fanzines and supported each other at concerts so that “violent macho dancing” in front of the stage wouldn't drive them to the back. Riot grrrls' energy quickly spread throughout the United States and beyond, inspiring many girls and women. They came to identify themselves this way also not only in Europe (the Riot Grrrl network), but in Latin America too. The mainstream's first general reaction was shock, with newspaper articles about naked, men-hating Amazons; later on, the music industry created a tamer variety: “girl power”, as embodied by the Spice Girls.

Do Something

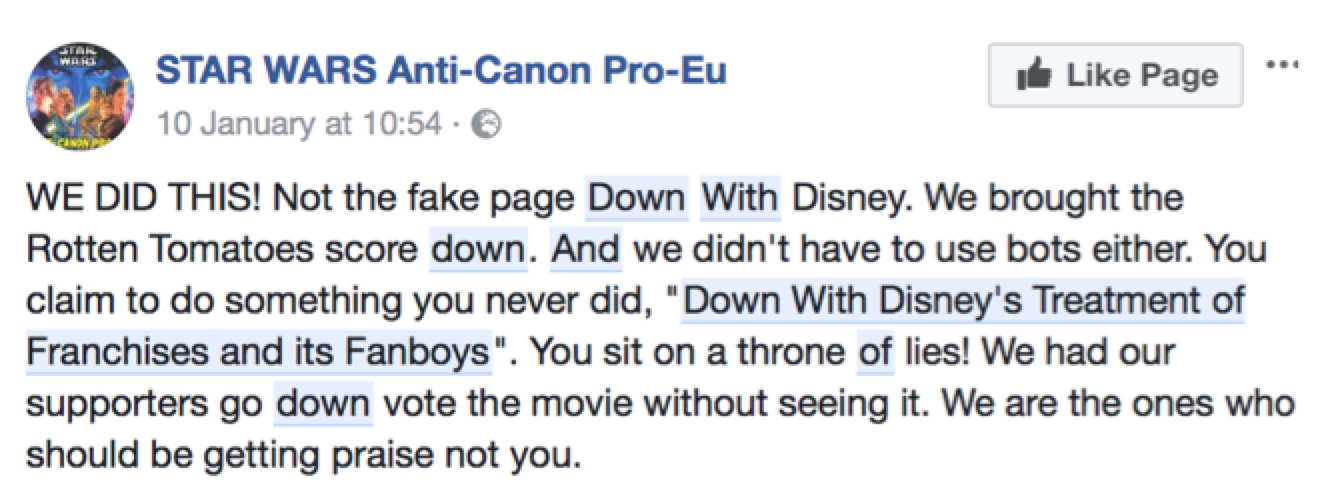

Bloody Mary #13, 2008

Bloody Mary began publishing in April 2000. At first it was also supposed to have been a girl band, but publishing a fanzine was deemed to be more accessible. Initially, the fanzine consisted of a few pages containing a mix of criticism of everyday sexism, light-hearted information about the standing of women in the world, mythology of strong Czech female personas, and rough humour both in writing and in the accompanying cartoons. Punk aesthetics alternated with cartoons by American feminist cartoonist Jacky Fleming, featuring a rebellious young girl. One front cover featured a depiction of Mona Lisa with the heading “The revolutionary force of women's laughter”.

Before Bloody Mary, a few other feminist fanzine issues were published: these were the Wica (1993-1996) and Esbat (1995-1998) fanzines, and the Brno-based Potměchuť fanzine. The first two originated from the punk scene and had an eco-feminism zest to them, the last-mentioned one was focused on womens' writing. Bloody Mary, whose editorial staff I joined in 2001 with an eager longing to “do something”, shared similarities with punk fanzines. Around the year 2000, things began to stir up somewhat–there was a wave of anti-globalisation sentiment in the Czech Republic at around that time (there were protests against a conference of the International Monetary Fund in Prague in 2000), which inspired many people to become active, which was also true for feminism. Before, the term was deemed a profanity, and it was thought to be inappropriate to step outside the norm of femininity. For example, journalist Ludvík Vaculík stated his aversion to young women in comfortable clothing which he deemed too “unwomanly”, who don't act seductively enough–“almost like men”, in an article titled “Neženy” (“Un-women”), published on 2.2.1999 in the newspaper Lidové noviny.

But it was around that time that things started to change. A new generation of left-wing activists started to identify with feminism and to give it positive connotations. One of the effects was the renewal of public events during International Women's Day in 2001, not as a celebration of women one should buy flowers for but as an opportunity to bring attention to the unequal standing of men and women both in the Czech Republic and in the rest of the world. Until then, International Women's Day celebrations were an unpopular Communist-tinged festivity, while today the day is celebrated by the majority of Czech society. Bloody Mary originated from the same wave of excitement to do something to improve the world for girls and for women.

To be part of the editorial staff was exhilarating. “You were completely new, different. You emanated energy, you were playful and you were dead serious. My dream came true. This is how I wanted it as a young girl at university, this is how it could have been with girls from the band. But it wasn't possible back then, the people weren't there”, Pavla Jonssonová recalled of me.

Lenka Kužvartová, one of the Bloody Mary editors, recollects the first editorial meeting: “Back then in Utopia, Kamila and Blanka really captivated me. They were almost witch-like. They were strong and sharp-witted, they really enchanted me. There was so much energy in Bloody Mary, a rapturous, unrestrained, vibrant desire to move the earth and do something great”.

It was in Utopia, a cafe bordering on the Vinohrady and Nusle districts of Prague where people from radical left-wing circles met, that Bloody Mary editorial meetings took place for a number of years. We thought up article themes, discussed the fanzine's distribution or letters from fans, or even folded the pages of newly copied issues and stapled them together. It wasn't only work on feminist enlightenment, but also fun and a great time spent with girl friends.

Into the Scene

Stephen Duncombe writes in the book, Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, that fanzines create a fundamental transformation point from a person being a media consumer to his or her being a media creator (he wrote it in times before online media came about) and that's exactly what we did with Bloody Mary. In the spirit of the riot grrrl slogan, “we don't want to read boy zines about boy things anymore, we want to read our ‘zines about our things”, we grabbed for ourselves a slice of “empowerment”. “Troublemaker girls of the world, unite!”, we proclaimed.

On the skeleton of the fanzine, which we set out to be a combination of playful gutsiness and criticism of issues we've experienced, we added fleshing the form of varying content: from interviews with interesting feminist groups, personas or bands, fact-based articles and personal contemplations, to parodies of psychology tests, life advice, or hoaxes.

We avidly discovered the world. We soaked up information about radical cheerleading, fabric menstrual pads, or the history of the vibrator from incredibly slow-loading English language web pages, and tried to bring all this new or long-forgotten information to light here in the Czech Republic. As time went by we started having theme-based fanzine issues, for example focusing on women fighters, sexuality, fashion, and the beauty myth, queer politics, or entertainment.

Bloody Mary was also starting to gain weight–a few issues had more than 70 pages, which was a lot for the time–and to lose speed. The intervals between issues ended up being one year, which was determined by both the extent of each issue and the inability to keep deadlines. In times of its peak fame, the fanzine was printed in 1,000 copies and was distributed in about 20 locations in the Czech Republic and Slovakia–after we'd have them copied on copiers and assembled and stapled the individual pages together at home by hand. We even started a blog after a few years, where we published individual articles and news which wouldn't wait until print.

Bloody Mary was oriented mainly towards the punk and hardcore scene. This was reflected in the language used (colloquial at times or using swear words, sometimes intentionally nonsensical articles) and the graphic design: copied pages with bad quality photos, scattered design, skulls and leopard skin patterns, chains and pyramids, and lots of collages. We brought attention to sexist articles and commercials in mainstream media, for example with names such as “Bra content betrays intelligence” or “Erotica glazes over the minds of men”.

We often got annoyed with the Esquire lifestyle magazine for men (and later Maxim), which was based on a derogatory and objectivist attitude towards women: it didn't view women as partners, mothers, or friends, but as creatures from another world who lie and have strange quirks, but because they offer hope of sex, are to be subjugated using secret tricks and then gotten rid of as quickly as possible. Such overt sexism isn't taken as matter-of-factly anymore–this has changed.

But the 2000s were still a time when it was uncommon even on the punk scene for a girl to be playing a guitar in a band, have a distro or seek consent in sex. These were all stereotypes that filtered through into punk from mainstream society – that is how we were all brought up. The word feminist was still a swear word, as attractive as an obnoxious illness. We had many hateful comments on our blog, such as “I wouldn't even prop my bike against you”– that was one of the more benign ones. Many of themes, primarily ones dealing with female sexuality and physicality in general, were simply taboo.

To Step out of Subculture

A reaction to this style was the feminist magazine Přímá cesta (Direct Path), which was published by the Anarcha-feminist group in November 2001 in Prague. One of the group's members, Markéta Štěpánová, recalls that for them, a fanzine wasn't a suitable format for spreading anarcha-feminist ideas; moreover, the first issues of Bloody Mary were unacceptable to her from a feminist point of view: “I had to start my own magazine. I said to myself, let's do more serious feminism”.

Even though the editorial staff could be labelled as punks, Přímá cesta contrasted with Bloody Mary because it wanted to step out of subculture and reach a broader audience. This was reflected in the use of a more refined language style, layout, and wider distribution–along with punk distros, it was also distributed through a number of regular bookstores. The themes and viewpoints were radical; however, many of them were revelatory for both the feminist and the anarchist scenes. Themes included parenting and upbringing based on anarchist principles, norms in sexuality, or feminism and mental illness.

The motivation of Přímá cesta to break out of “ghetto” subculture was clear: feminism and gender studies gained respect only very slowly in mainstream society. There were only a few non-profit organisations that concerned themselves with women's rights (Prague Gender Studies or proFem, who were in fact also involved in both Bloody Mary and Přímá cesta, or Nesehnutí in Brno). These were considered too reform-oriented for anarcho-feminists, as they lacked the scope for covering a wider breadth of themes and for getting down to the roots of oppression.

Non-profit organisations also began to concentrate on specific themes: thanks to (not only) proFem, domestic violence became an issue that was brought to public awareness, Gender Studies focused on gender equality in labour markets, Fórum on 50 percent of women in politics. These themes were more or less acceptable to the general public, but this also caused more fundamental issues to be missed. Awareness of some of these was only brought about by current feminist groups: Konsent sought awareness of sexualised violence and consent in sex, Čtvrtá vlna concentrated on sexual harassment and disparagement of women on universities, but also on criticism of consumer society in general.

Looking back, it seems incredible that for eight years, there were two radically feminist magazines, both with fairlylarge print runs, being published in parallel. Besides that, I really do feel that these activities really meant something – they broke down the worst prejudices and sexisms in the scene, and hopefully also in society in general. I ask myself, where are the people who read those magazines and shared these thoughts – what did they do when these magazines stopped being published? Why didn't they take up the glove?

Our reasons for ending the magazine's publishing can be summed up as exhaustion: exhaustion of themes, personal exhaustion, maybe even exhaustion of those friendly and co-operative relationships in groups. And also, it was definitely an exhaustion of the form. Around 2010, you could find everything you wanted to know about feminism on the Internet – why release a printed fanzine once in a blue moon? For me, the girly giddiness of Bloody Mary also became somewhat limiting after I turned 30. For a while afterwards we released the radically queer Q_Kvér zine where we tried to break down gender norms in sexuality and identity and where we experimented with the format and with language: how to fit into the Czech language (which has grammatical gender) the notion that gender identity isn't about two opposing poles, but a varied space, or at least a scale? We also organised a few genderfuck events, but then even that stopped.

Destroy and Build up Differently

For a while it looked like feminist fanzines died out here. And then I saw filmmaker Martina Malinová asking people on Facebook to come up with a name for a new feminist zine. And, a few weeks later (April 2017), I bought it at the Brno zine fest. It's called Drzost (Insolence), it's got a pink cover with a beautiful illustration, it's full of drawings and collages, informative articles, essays, and poetry, exasperation, solidarity and proclamations such as “Rebel girls, welcome”. “I've always loved zines. It's the most natural form of expression for me. When I go to a demo it's OK, when we do a happening it's great, but for me the best thing is to make a written mark somewhere”, Martina says, noting how important cooperation is to her. “I can't say what's more important, whether the fact that the zine's printed or the process of making it. If I was making it alone I wouldn't have as much joy from it.”

She tried to encompass the diversity of people and their feminisms into Drzost: queer activists, mothers, teenage girls, and fifty year olds, people both in worker professions and in academia, men, women. The content is changing like the landscape in the movie Stalker. During my first read of the zine, I had an impression of a little girl's bedroom, where you can talk about favourite books or homemade cosmetics with others; during the second read, I opened the pages at an article about the body and the beauty myth; the third time I started getting into articles about the culture of rape, about inspirational women with migrant past, about peace activists or about criticism of inequality of women in the Czech Republic from the point of view of a male-feminist.

Drzost is printed in colour on glossy paper and isn't stapled but bound, the print run is about 200 copies. In this respect it's similar to other fanzines, as printing technologies are more and more accessible, so fanzines look like professional publications. Moreover, zines today are as much an artefact as a source of information, so the visual side of things has gained importance. Drzost, in contrast to other zines, goes back to cut-and-paste style graphics, with pages created using real collages instead of on a computer. You'll find on them handwritten notes or dried rose leaves. It's very personal in some respects, being reminiscent of a lovingly kept diary. At the same time it's similar to punk feminist zines thanks to its aesthetics, themes, and its roots in DIY culture. Martina is from a world where she read Bloody Mary a few years ago, and for her, Drzost is also a culmination of many activities.

I found another feminist zine shortly afterwards. It's called Obrovská (Huge) and it has been published by journalist and musician Mary C since 2016, so there are now three issues of the zine out, each with 50 printed copies. It's a booklet with a clean black and white design and contains information about interesting women and women pop culture groups and also interviews with a number of women artists (it also exists online). A female network is also in creation on the fanzine pages. As with Bloody Mary, I feel in it an aspiration to bring to light and connect interesting and creative women. Apart from frustration from inequality, prejudice, and violence that happens to women every day, what is also frustrating is that women are often isolated in their frustration. It's great to connect these voices of criticism and make a stronger current, which is also why Mary C plans for the next issue to be conceived as a Huge editorship and plans to invite other interesting people to take part in the zine's creation.

The fanzine's name comes from music composer Jana Obrovská and presents many strengthening connotations which aren't normally associated with the norm of womanhood. For Mary C, the writing of the zine is also connected with strong emotions: the fanzine functions as a kind of diary where she notes what she liked and what made her angry. She deals with the topics of sexism and other forms of oppression, for instance racial oppression, in her writings, but she tries to stay on a creative level.

“I need to be resistant and active–to keep at a certain level of being pissed off, but not so much that it destroys me.” Writing a fanzine effectively means searching for one's expression, a way to find one's voice. The torch of feminist zines is thus now being carried by women artists and activists over 30. Mary C also has a different background that led her to writing fanzines: “I don't come from a punk or anarchist culture. My resistance and self-awareness comes from the Afro-American community. I grew up listening to jazz, blues, and funk music, where there were often strong women characters”. She began to make music, organized women artists' concerts, and is preparing mentoring for girl musicians; a fanzine is another piece of the puzzle.

When we started with Bloody Mary, I was around 20. We asked new questions, spoke with a new tongue, and we had to stomp, shout, and beat our shields to dismantle everything that was here before. Current zines now function in a different world. Feminist issues are already around and being spoken about, but we still don't live in a world without inequality, prejudice, and hate.

At first sight, I don't see continuity between the individual chapters in the history of Czech feminist zines. Like Bloody Mary before them, neither Drzost nor Obrovská were created with what came before in mind. Fanzines are more of a reaction to what's happening around them there and then. With Bloody Mary, we didn't follow up on samizdat literature, but reflected on what was going on in the West at the time. Markéta Štěpánové from Přímá cesta reflects on this: “That's exactly the point of a zine–each generation discovers the world again, in their own way. What came until now, they're trying to destroy and build up again differently."

—

Jitka Kolářová (*1980) studied humanities and media studies at the Charles University in Prague. She published, alone or in co-operation, the fanzines Bloody Mary, Q_Kvér and Femidom, and co-organised numerous female and feminist band concerts and the radically queer Gender Fuck Fest festival. She worked in the Gender Studies and Jako doma non-profit organisations (helping homeless women).