The Czech Zine Scene (Part 1): Setting the Stage

/Several years ago, I hosted a series of articles on Participatory Poland, curated by Agata Zarzycka and Justyna Deszcz-Tryhubczak from University of Wroclaw. The series touched on the shifts occurring in a Post-Communist country as it embraced forms of consumer culture, developed strong traditions of popular and participatory culture, and reached out to larger transnational networks. I ended my introduction to this series with a call, " hope you will learn as much from the Participatory Poland series as I have, and I hope that it will inspire scholars in other countries to consider producing similar accounts of what participatory culture might mean in their national contexts. I would love to see proposals from elsewhere which might fill similar gaps in our understanding of traditional and contemporary cultural practices." Today, I renew this call, but with a second example of what such a discussion might look like.

I met Miloš Hroch and others in his circle when I was passing through Prague several summers ago and we have an passionate and engaged discussion about various forms of fan and participatory culture. When he released a book in the fall which brought together a range of experts on different subcultures in the Czech Republic, to document the history of zine production in that country, we hatched a plan to feature some of those essays here -- a sample of the greater range of material to be found in the book, I Shout, 'That's Me!": Stories of the Czech Fanzine From the 80s Till Now. Over the next few posts, we will drill deeper into what roles zines about games, science fiction, popular music, Feminism and other topics played in the cultural transitions that the Czech Republic has undergone over the past few decades. As Hiroch writes below, "Civic involvement lost all meaning in an atmosphere of incessant control; people could not express themselves freely at work, so they found an outlet in hobbies." So, these writings, often directed towards other, less political topics, can nevertheless tell us much about how people lived their lives, how they made meaning of their experience, in a world that once seemed so restricted and now seems in so much flux.

Once again, I hope that sharing these accounts here encourages other scholars to consider what participatory culture means in their local contexts. I would welcome proposals from other groups who wanted to use my blog as a platform for sharing their experiences and perspectives. I freely acknowledge that my own ideas about participatory culture have taken shape almost entirely within an American context, reflecting my own experiences as a fan, and growing out of my ethnographic work here. I want to see these ideas tested against political, cultural, economic, and legal contexts very different from those of the United States rather than having these ideas universalized and applied uncritically to these other contexts.

Have You Ever Tried Putting a Mentos into Cola?

By Miloš Hroch

The immune system of some individuals is resistant to it, other succumb to it without hope. Publishing fanzines is an illness, as will confirm anyone who's ever waited in long queues at the post office to send his fanzine to the other side of the country, or who nervously fidgeted at work, waiting to use the office copiers when the boss isn't looking. The symptoms are described in the handbook How to Publish a Fanzine: “You can tell by getting up at 6AM to write a few more lines before you go to work, and end up calling in sick because you can't stop.”

The fanzine fever started among a group of science fiction enthusiasts in the United States in the 1930s, and from where it spread to the rest of the world. In the Seventies, punks would get dizzy reading fanzines, the feeling often being similar to the effects of sniffing paint thinner; the most famous fanzine was incidentally called Sniffin' Glue, and was published by former bank clerk Mark Perry in his London flat. He was the first to let the world know about the Sex Pistols, long before established musical magazines. “Don't like Sniffin' Glue? Start your own!” was Perry's challenge - and a lot of people caught on.

Fascination and Frustration

The epidemic's spread was unstoppable; decades later, literally almost everyone in America published fanzines. Theorist Stephen Duncombe offered the simpliest definition of the medium in his book Notes from Underground, published in 1997: “Fanzines are nonofficial and noncommercial magazines published independently in compliance with the code of DIY ethics and are distributed through underground concerts or by hand-to-hand contact.” Fans of fringe or as of yet unknown music and literary genres or board games would publish them of their own initiative; there were fanzines about motherhood, feminist ones, queer magazines, and also anarchist ones for organising demonstrations.

Contrary to this trend, American Dough Holland's Pathetic Life fanzine was conceived more along the lines of a personal diary, where he would reminisce about his worst part-time jobs or contemplate his being overweight. The Kill Your Television fanzine published about the toxic influence of mass-media, Factsheet Five published reviews of other fanzines exclusively, and one of the most famous fanzines, Dishwasher Pete, was about washing dishes – that is, about a care-free ride through the kitchens of almost all of the United States and about rejecting the consumer dream. The fanzine created a forum for other kitchen helpers, who could connect with one another and share their experiences. The intention of the author, Pete Jordan, was to give a voice to people who would otherwise be overlooked or would not be listened to—and that's the essence of fanzines.

Where else would you want to learn about the Hardcore-Punk scene in Malaysia or in Slovenia than in the influential fanzine Maximum Rocknroll, which has been published for almost 40 years now thanks to an extensive network of volunteers, and where Matt Groening of The Simpsons fame began to draw in the eighties. Maximum Rocknroll sticks firmly to its guns: accepting no funds from corporations and publishing no reviews of big label records.

The drive is, as always, "fascination and frustration." Without the first, fanzine authors wouldn't be so devoted and ready to learn from mistakes; without the second, they wouldn't have the strength to fight for their self-determination and their own small utopias. That was reward enough for them. Amateur magazines were always published and disseminated by determined outsiders with grapho-maniac tendencies—even though some may have later on become members of famous bands, sci-fi writers, poets, music journalists and publicists, cartoon illustrators and photographers, or artists at the forefront of new artistic genres.

At times, the fever would subside or have a less obvious manifestation. Other times, it would break out even more intensively, or disappear completely—the infected would lose their ideals, shift their priorities to work and family; for others, fanzines would lose their meaning with the onset of the Internet. But the bug never disappeared completely, and neither did the symptoms: assorted breaking of grammar rules, ignoring of formal newspaper and magazine rules, crazy drawings and hallucination-inducing cartoons. Even though the letters on the page may begin to disappear due to a weak typewriter stroke or not enough paint in the printer cartridge, the mark of a contagious and obsessive undertaking remains on fanzine pages to this day.

According to Henry Jenkins, fanzine authors formed a digital community even before it was technologically possible—they were a sort of real-world Wikipedia. Based upon his knowledge of fanzines, Jenkins put forward a theory of participatory culture, which describes the behaviour of users in a Web 2.0 environment. The circle hasn't closed yet. The nostalgia that drives today's popular culture doesn't draw us back just to vinyl and cassette tapes, but also to paper. Despite ongoing talk of the extinction of printed media, the microcosm of independent printing is expanding.

Make do without a bottle opener

The Czech fanzine fever that this book portrays through several examples also had (and has) other carriers of the bug. DIY publishing's origin isn't necessarily an expression of enthusiasm; it can also originate from oppression, fear and severe deprivation caused by the cultural and historical conditions that were present in former Czechoslovakia during communism. The hitherto untold stories of Czech fanzines are therefore immensely exciting and adventurous. They're driven by at times obsessive curiosity and quirky DIY approaches, and are also a testament to the prevalent atmosphere in society at the time, the essence of the past regime, and to the strategy of survival within it.

One only need to remember the Czech beer bottle opening trick: it always fascinates friends from the West, who are usually stuck without the appropriate instrument. A beer bottle can be opened using a table, a lighter, teeth, or even paper folded several times over. Domestic DIY zinesters didn't have access to Western music, books, comic books, movies or fanzines; they couldn't publish without censorship. They didn't have their bottle opener, but they managed. They also had something to follow, and sources to learn from.

Formerly communist Central European countries have a special word for self-publishing: “samizdat”, a term originated in the Soviet Union in the 1940s. It is a paraphrase of the word “Gosizdat,” a nickname for large, official state publishing house. Samizdat (“samo” meaning “self”, “izdat” meaning “to publish”) meant to be in opposition to that state publishing house. Before 1989, Czechoslovak dissidents used samizdat to distribute manifestos, foreign magazines, letters, literature of domestically-ostracized authors, and translations of banned books, which volunteers used to hand-type using typewriters and carbon paper and all under threat of interrogation or imprisonment. The more efficient means of printing were under strict control of the regime.

Samizdat didn't necessarily have political content, but it did have political significance simply by virtue of its existence within an oppressive regime. It originated in the fear-infused 1950s and became a tool of intellectuals, dissidents who criticised the regime, and also underground artists. This is the musical and artistic community which Ivan Martin Jirous, the main theoretician of the Czech underground, defined in his “Notice of the third Czech musical awakening.” He described it as a movement which creates its own distinct world aside from established society; a world with its own internal energy and a different aesthetics, and as a result, a different ethics.

In 1976 Vratislav Brabenec the member of the persecuted avant-garde band Plastic People of The Universe (the symbol of the Czech underground movement, their music was inspired by the Velvet Underground and by the artistic group Fluxus as well) was among others arrested and protests against this fact culminated in the formation of the Charter 77—an appeal by dissidents and intellectuals criticized the violation of human and civic rights that Czechoslovakia had sworn to uphold by signing the Helsinki Accords. The regime reacted by a propaganda campaign that depicted members of the underground culture as dangerous elements. Two years later fans of the Plastics began to publish Vokno magazine, a cultural underground bulletin. “The first series was thematic, each issue had a theme—music, literature, art, and others,” recalls František Stárek, its “publisher”.

Vokno was printed on an Ormig grain alcohol copier, which was assembled over a period of several months from parts stolen from an office machine factory. The magazine was the predecessor of domestic music fanzines. One could read about the Velvet Underground or about Czechoslovak experimental bands in it, but no names of authors were present, nor real names of villages where underground concerts took place, unless the concerts were broken up by police and subsequently written about in the official Rudé právo (Red Order) newspaper.

The cultural underground and the activities of samizdat journalists is well documented. This book is more aimed at fanzines, which can be considered as being in the shadows from a historical perspective. All of the underground authors however share a common zeal, even if the forerunners were more closely associated with political opposition and faced interrogations by the secret police or even imprisonment. The passion is evident in an excerpt from a poem from the Grey Dream anthology, written by Pavel Zajíček, a member of the underground band DG307, in a 1980 text: “I was transcribing some lyrics deep into the night; I could feel their birth, and their mirror in sounds. However I don't have strength to involve someone else—I think it's best to do EVERYTHING on my own”.

We'll leave you alone, you leave us alone

Without anyone knowing that it was called DIY, that is, Do It Yourself, all around the world, local fanzine makers had one thing in common with their foreign counterparts: a stubborn conviction that they can do everything on their own, without the money or help of others. In contrast to the rest of the world however, there was one significant difference—desperate deprivation not only in cultural goods, which was reflected into both the content and the methods of fanzines.

All things Western had an aura of forbidden fruit around them—this was the reason why people from Czechoslovakia and other communist countries desired them. If they were to fulfill those desires and ambitions however, they had to be creative and manage on their own. When skateboards were the craze of the young generation in the West, the first such item in Prague was copied by the locals using any available materials: the wheels were made from garden hoses and the iron trucks were cast at home using homemade forms. Rare vinyl records obtained from friends traveling abroad or from street garage sales were used to learn not only English, but also whole musical genres. Foreign magazines were avidly read.

Teenagers imitated English words, Czechoslovak punks used wax to hold their mohawks up and bashed into their guitars. Not only that, but foreign fashion magazines found their way into the country through often complicated paths; those were used to inspire home-made copies of Western fashion styles. The clash of different ideas and desires was epitomised by the Berlin wall, dividing Eastern bloc and the Western one, the world of Marx and the world of Coca-Cola.

The Russian-American historian Alexei Yurchak describes the symbolic overcoming of boundaries in his book Everything was Forever, Until it was No More: The Last Soviet Generation using the term “Imaginary West”. People lived in an information vacuum, in both real and cultural isolation, and could not travel freely or dress according to trends or like their favorite bands. They couldn't do anything without state supervision—but they desired to so much that they created their own version of the West within limitations set by the state. All of these factors were behind the origin of the first true Czechoslovak fanzine, created at the beginning of the Eighties by a group of science fiction fans at the Mathematical-Physical Faculty in Prague: “We want to publish fanzines like in the West too!”

At this moment, the fanzine virus mutated from the Czechoslovak tradition of samizdat. There was also another agent of the mutation: an ingredient of Real Socialism, the Czech phenomenon of chatarstvi, or cottage-going. This was a phenomenon when whole families would leave large cities during the weekends and travel to the countryside, where they might own a small house or a cottage, and would spend the weekend there rather than in the city.

It was in effect a reaction to the complete control of the Communist regime, the limited options for traveling, and to the development of large prefabricated estate housings. The transformation of original urban housing began in the Fifties, and all across the country, standardized, uniform panel blocks sprang up. The greyness of the times and the cramped living conditions in the “rabbit-hutches” was depicted perfectly in Věra Chytilová's film Panelstory (1981). Cottage-going provided a care-free time in a grey zone that was of no interest to the governing regime – similar to publishing fanzines.

Civic involvement lost all meaning in an atmosphere of incessant control; people could not express themselves freely at work, so they found an outlet in hobbies. Cottage-goers worked on perking up their cottages, others would become members of fishing clubs or would collect stamps or make model airplanes or publish their own magazines and share their enthusiasm for what interested them but what couldn't be found in shops and what wasn't written about.

Fanzines were an ever-changing zone with different ratios of the above-mentioned ingredients. Although something of a reduction, it's possible to separate Czechoslovak fanzine creators into two categories: dissidents and cottage-goers. The first were forced through the content, their stubbornness, and principles to come into conflict with the regime; the second accepted the regime's terms so that they could “only” devote themselves to their hobbies. They had no need to resist. They even had de facto state approval, as the state encouraged and supported “spending quality free time.” It was an unspoken exchange: you leave us alone, and we'll leave you alone.

The stories of fanzines are therefore also stories of our past: in these past zines we read science fiction and metal fans obsessively making up music charts and takes us into the grey (cultural) zone; computer game enthusiasts documenting technology shows the at-the-time technological lag behind the West, and comics book fans show us the desire to create their own superheroes and to domesticate the originally American medium.

Total Ink Madness

The aim of this book isn't to map domestic fanzines in detail, but rather to introduce the topic to a wider audience and to tell the stories of some of those who gave us the fanzine bug. American and British fanzines are fairly well-mapped; the fanzine scene outside of these two countries is perhaps not so well documented, with information being available primarily within a closed circle of scholarly studies. The ever-expanding Archive of Czech and Slovak Subcultures which was established in 2014 is doing a good job and there one can find and browse through most of the fanzines mentioned here. The collection is however not nearly as extensive as the Prague-based samizdat archive Libri Prohibiti.

In documenting Czechoslovak and Czech fanzines within this the scope of this book, it is important to note one more thing. Domestic historians don't agree that even after the November 1989 events, there could be dissidents, people who would have a desire to resist and in a free society. In this book, the term “dissident” is used in a way that most scholars would not agree with: for us, the important factor is that of self-determination and resistance in the most general sense. It doesn't matter if it is resistance against a regime, stereotypes in society, the music industry, or the mechanisms of the art trade.

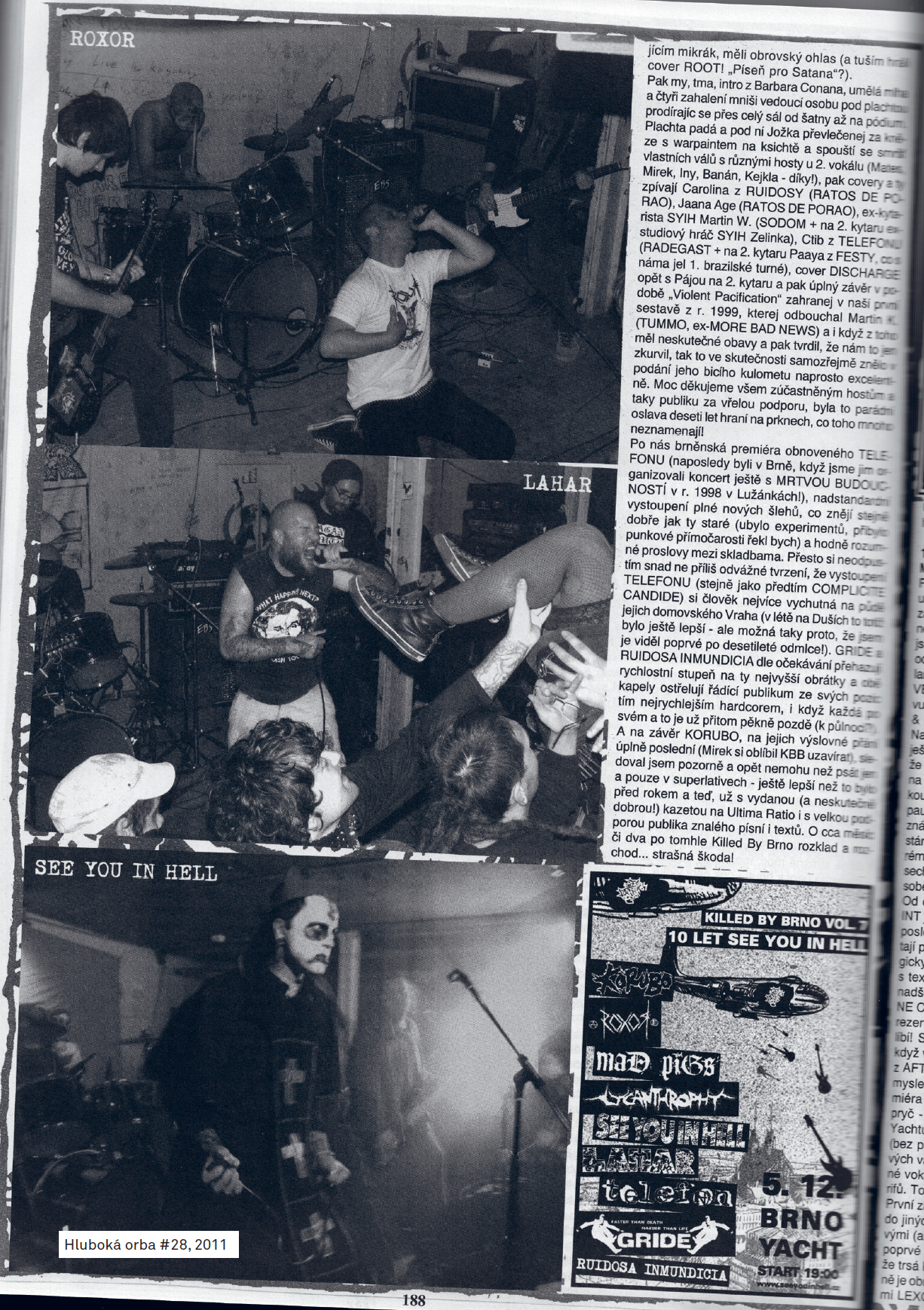

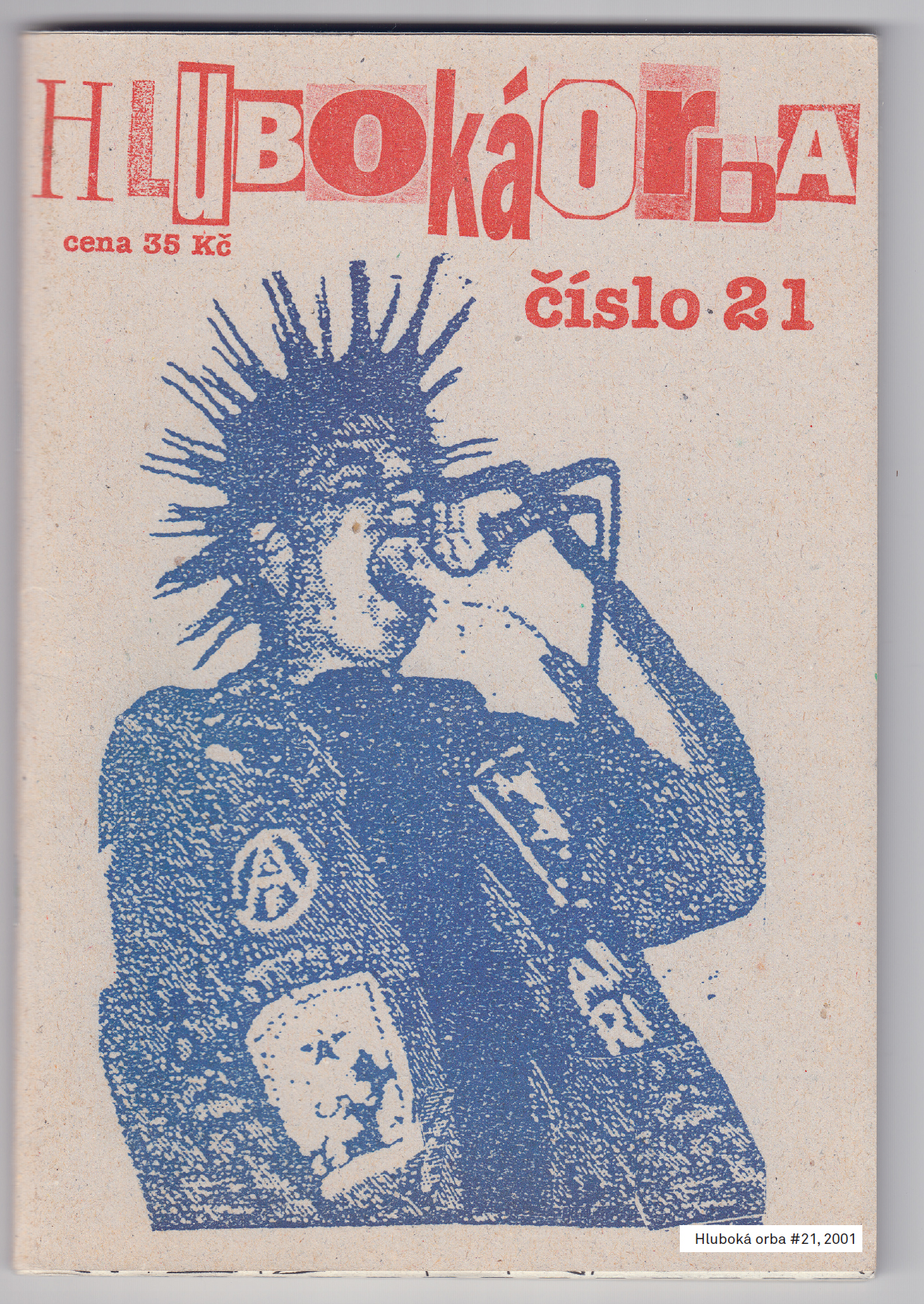

For the hardcore-punk community, loud guitars were a political statement about how the Velvet Revolution ideals of empathy and solidarity were fading away. Music once again became the language of resistance through which, people voiced their opinions on ecology, anti-racist, or animal rights issues and of course, anti-capitalist sentiments. Feminist fanzines on the other hand made significant contributions to the discussion and thoughts about the standing of women and gender roles in society.

The photographers of the latter years of the first decade of the millennium are dissidents of sorts, authors of one of the latest kind of fanzines. They transform their photos into zine notebooks printed on cheap copiers, and even though many consider this to be a mere fetish, a few authors see their prints as a protest against the superficiality of visual communication in a digital environment, a protest against an art world driven by ego and marketing theories.

Their notebooks, bordering on artist books, are published in minimal numbers and often disappear sooner than they can be taken notice of. You take a few photos, do some typesetting, print, copy, fold over, staple, bind together, crop, and annotate. “Have you ever tried putting a Mentos into Coke, or did you only watch it on Youtube? It's good to experience things for real once in a while”, says photographer Petr Hlaváček, a Czech pioneer of such photo zines. He subscribed to zines from abroad and followed the Tiny Vices photo blog that was active from 2005 until 2012, where one could primarily see snapshots taken from the hip, depicting both bizarre things and the banality of everyday life. This lead Hlaváček to making the collective zine Repetitive Beats around the year 2008. “Total ink madness”, reminisces this inconspicuous man in his thirties with a knit cap on his head.

Cottage-goers and Dissidents

In this respect, it is important to note in this context another specific dimension of Czech, or Eastern European fanzines in general. The inspiration isn't only one-way, from West to East. David Bowie fell in love with Warsaw during a train journey there and named a song after it on his album Low, the first of the Berlin trilogy. Warsaw was also the original name of a four-piece band from Manchester, now better known as Joy Division. The album The Dignity of Labour from Sheffield synth-pop band The Human League was inspired by the Soviet space program. Nick Cave wrote the song "The Thirsty Dog" in a bar of the same name in Prague, and Thom Yorke of Radiohead got the idea for the song "The Tourist" from the breakthrough album OK Computer while watching crowds of tourists in Prague; he went on to include sounds of the Prague underground in the Paranoid Android single. The British band Broadcast wrote a song inspired by the imaginary movie Valerie a Týden divů (Valerie and her Week of Wonders) from 1970 – and that's not the end of fascination by Czechoslovak New Wave in the West.

Polish cultural theoretician Agata Pyzik named her book Poor but Sexy after the slogan that was used after the fall of the Berlin wall to ostentatiously promote Berlin as a city with a rich cultural and historical capital, in spite of lacking the economic one. Pyzik in her book borrows the slogan for the analysis of Polish pre-revolution culture, which has a lot in common with ours.

We were poor and had limited means and resources, but in spite of this, the architecture, music, movies, books, illustrations, and not least fanzines carried a sense of something exotic for the West. Much was lost in the translation, but it was perhaps because of this that a very uncanny culture arose here. “We are still influenced by the geographic logic of East and West,” writes Pyzik with a critical undertone. The story of amateur magazines and their quirks didn't really end in 1989, as many would think. Fanzine makers, cottage-goers and dissidents alike, are still here. And they still carry the DIY spirit and curiosity, formed by cultural and historical context.

Fanzines are still incubators of new artistic directions, and are still detonating fuses of social revolutions. On the periphery of the mainstream media world, off the newsagent stands, lies an underground world of independent, DIY-created magazines. If we choose to disregard these publications that stem from folk creativity, we are losing out not only on adventurous stories about their origins; how media DIY-ers and poachers create in a landscape of popular culture. We not only lose out on knowledge about them, but also about us.

.............................................................

Miloš Hroch (*1989) studied journalism and media studies at the Faculty of Social Sciences of the Charles University in Prague. He continues his doctorate studies there. His research interests are alternative media, fan studies, cultural studies, popular culture and subcultures. Since 2013, he has been a music editor at Radio Wave (Czech Radio). He publishes articles in Respekt weekly magazine, in the A2 cultural fortnightly magazine, in the Hospodářské noviny newspaper, in the Fotograf magazine or in the Živel magazine. He contributed to the Lidové noviny newspaper, Orientace LN, or His Voice magazine. He participated in the making of the book Prkýnka na maso jsme uřízli (We Saw Up a Cutting Board, 2013) about skateboarding before the 1989 revolution, the Kmeny 90 publication (about Czech 90´s subcultures), and the Oáza (Oasis, 2016) book in co-operation with the Text Forma Funkce (Text Form Function) graphic design department of the Art Faculty of the University of Ostrava, which documented the Silesian music scene. He co-founded the Křivák/Crook skateboarding fanzine.