Confessions of a Superhero: An Interview with Filmmaker Matt Ogden

/ Earlier this month, documentary filmmaker Matt Ogden released his most recent film, Confessions of a Superhero, on dvd. I first became aware of this film, which depicts the personal lives of the people who perform the parts of superheroes in front of Grauman's Chinese Theater in Hollywood, when it played at the South By Southwest Film Festival in Austin. Ogens' previous work includes Timeless and The Life for ESPN,

Earlier this month, documentary filmmaker Matt Ogden released his most recent film, Confessions of a Superhero, on dvd. I first became aware of this film, which depicts the personal lives of the people who perform the parts of superheroes in front of Grauman's Chinese Theater in Hollywood, when it played at the South By Southwest Film Festival in Austin. Ogens' previous work includes Timeless and The Life for ESPN,

Players for VH1, each of which deals in one way or another with the colorful personalities behind the scenes in sports and show business. The film is hauntingly beautiful, showing us something of the fantasy lives of its protagonists, as well as heartbreaking in its depiction of these men and women, their motives for performing, their professional dreams and disappointments, and the society they have created for themselves. There are places where the film edges a bit too close to pathologizing its subjects for my taste, but there's always something to complicate any easy judgment we might want to make about these people and the choices they've made with their lives. You can learn a good deal more about the film over at their engaging homepage or at Myspace. You can also see some sample sequences on Youtube, including this sequence of Superman working the streets, an exploration of the economic realities of street performing, The Hulk's account of his struggle to escape homelessness, and a sequence showing the superheroes at home getting ready to perform.

What first attracted you about this topic? In your Director's statement, you describe a process which takes you from estrangement towards a closer identification with your subjects. How did this reassessment of these people and their lives come about?

I'm always attracted to stories about the underdog, about people on the fringes of society, or just interesting, sometimes quirky characters. At first, I thought it would be an oddball comedy documentary. Who would dress up and work for tips on Hollywood Boulevard? After we began production, Los Angeles became a character in itself. The city draws so many different types of people from all over the world seeking fame and fortune. It's a cliché, yet it's true. As I delved deeper into filming, I discovered these "superheroes" aren't much different than myself on the inside; and not much different than the other seekers in Hollywood. They want to make it. They want success. Deep down they want to matter, to make a difference. Don't we all want that, whether it's through acting, as a doctor, lawyer, entrepreneur, or teaching? Success comes in many forms - money to some, awards to others, a sense of accomplishment, et cetera - but in the end we all want to feel like we're enough. It's easy to judge people that are different. At first glance most would say they do not relate to these characters. But stick around and get to no anyone and you just might find something you have in common. I did.

Many of your earlier films -- The Life about sports, Players about Ludacris -- dealt with celebrities in the traditional sense of the word. This film deals with people who see themselves as having found fame but not fortune, as one of the characters puts it, having acquired fame for the characters they perform but not as a result of their own personalities. How did that earlier work shape your perception of these people? What did making this film suggest to you about the culture of celebrity?

I'm an idealist. I think celebrity is ridiculous. Then, why the hell did I choose this career, you might ask? I love it. I love telling stories. And I don't mind being paid for it, but I don't need the fame. I just don't care about Paris Hilton or Lindsay Lohan. People should be recognized, if it all, for being good at what they do, what they contribute, not for who they date or who they made a sex tape with. I'd like to think the other people I've directed whether it's a hip hop artist named Ludacris or an MVP in the NBA or NFL, are more than just celebrities. They are good at their chosen professions whether anyone knows their names or not - they are great at what they do. Celebrity is just a natural offshoot of that. It's when people become celebrities for doing nothing that I don't relate to. When it's not about their profession, but what they do when they're not working - that is not what I want to learn about.

The characters in my film have found a different kind of fame. They've been featured on Jimmy Kimmel, Jay Leno, in magazines and interview shows all over the world. But they're not household names. And most people don't know their real names. They just recognize them for the characters they portray. And there is nothing wrong with that. In Robert Fritz's book The Path of Least Resistance he states "the path by which you move from where you are in your life to where you want to be cannot be put into a formula." This applies to my career as a director, even more so to these characters. This is their path and the road they chose to hopefully find success in the entertainment industry. Who's to say they want find it? Not me.

As far as celebrity goes, I do feel kids today want to be famous as opposed to a great actor. They want to be filthy rich, drive a Bentley GT Continental and where a Rolex instead of playing basketball for the love of the game or making music because they have to make music. Entertainment is a means to an end for a lot of people. If you aspire to be a celebrity, well...good luck, I guess.

In your director's statement, you said, "At first I wanted to show the eccentricities of these characters, but I didn't want to take the easy route and simply make fun of them. I wanted to peel the onion and go deeper." What steps did you take to avoid the stereotypes and preconceptions that your viewers might have about these people?

I attempted to keep my point of view out of the film. Once you turn the camera on, even if you never ask a question, reality is manipulated of course. People act different in front of a camera. In most family photos everyone is smiling. As soon as mom points a camera at you, you're trained to smile. Same with moving pictures sometimes. But I kept myself out of it as much as possible. If you laugh at the characters, they're being themselves and I'm not editing it in such a way as to get you to laugh at them. Im just showing you, the audience, what happened. As I got to know them better while filming I began to empathize with them. I hope the audience will take the same journey I did and end up rooting for the characters by the end, or at least some of them.

How have your subjects responded to this film? On the one hand, you do give them a kind of visibility on the screen. As they suggest in relation to the news coverage of the arrest of Elmo and Mr. Fantastic, all publicity has a value in their world. On the other hand, you really don't pull many punches here in terms of depicting some of the painful and humiliating aspects of their lives. Yet, several of your subjects came out to South By Southwest to help you promote the film.

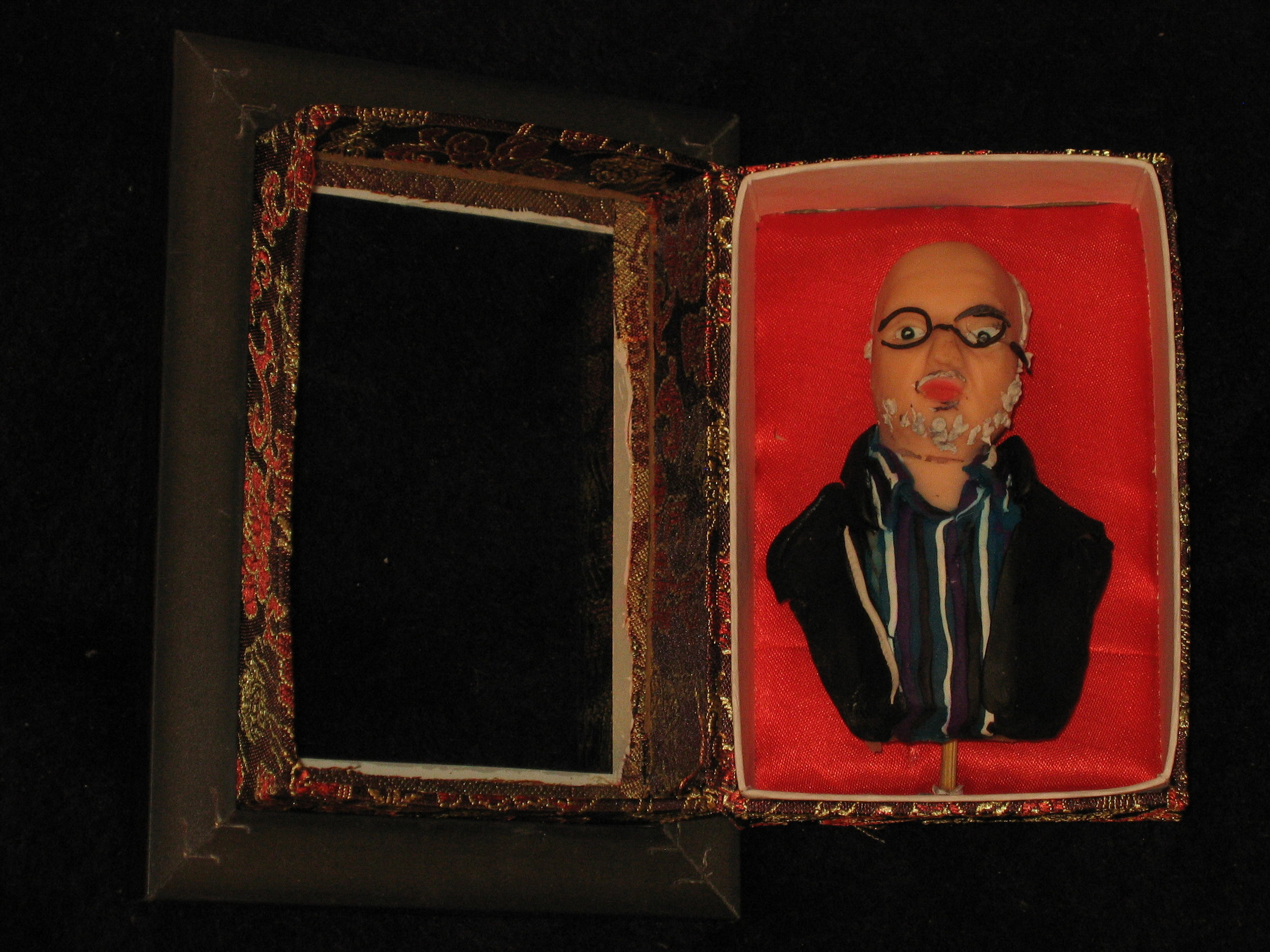

Certainly, I was concerned and curious as to how they would react, particularly Max, who portrays Batman. He is definitely the antagonist, or villain of the film, if there is a villain. Truth be told, I do not know how Max feels about the film. Chris "Superman" Dennis seems to love it. Some people love recognition whether it's for good or bad reasons. Bad publicity is better than no publicity. I'm sure there's a little bit of this in play.

At SXSW, Superman and Hulk were celebrities. People loved seeing them there. And they deserved the notoriety.

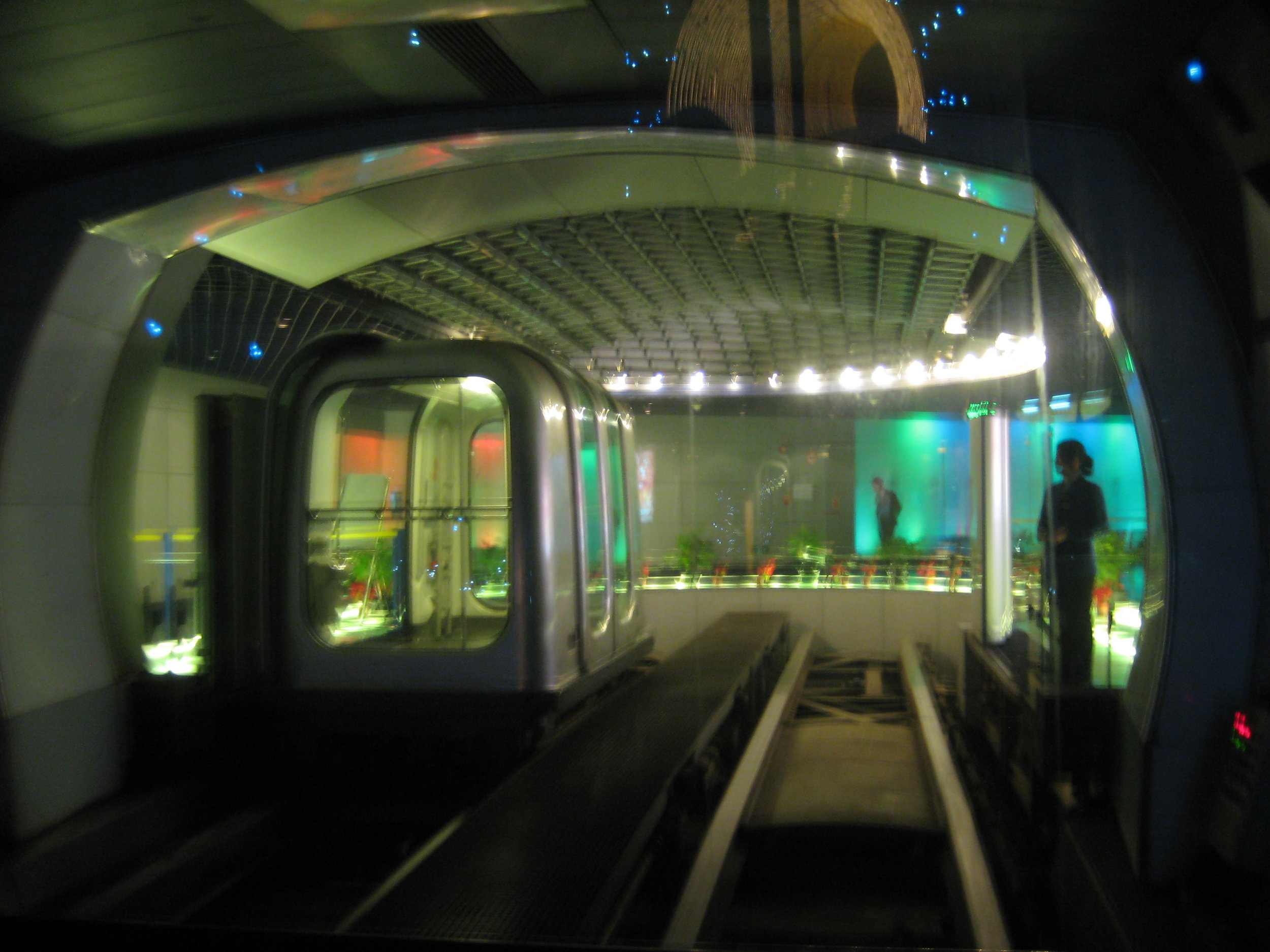

One of the striking components of the film is the visual style -- especially your use of still photographs and oversaturated colors. How did these two stylistic choices come about and what do they signal about your relationship to this content?

From the moment the idea came to me, I knew I wanted this to be a visual documentary. In my opinion, a film should look as good as the story its telling. Charlie Gruet, the director of photography and a producer on the film, set out to give a style to the film, and not just shoot willy-nilly. The idea was to make this look cinematic, filmic, like you're watching a narrative film, not a talking head corporate video. All of the verite moments on the boulevard were shot handheld, in a fly on the wall style. The sit down interviews, scenics of Los Angeles, and specialty shots were more set up and art directed. But we didn't make things look "cool" for the sake of it. Each set, if you can call it that, was discussed and reasoned. Superman was interviewed on a vinyl couch against patterned wallpaper as if he was in Martha Kent's country home in the movie or comic book versions of Superman. Batman was shot in a cavernous warehouse (instead of a cave), but you get the point. Batman's past is dark. And we wanted a darker setting for him.

In addition to directing, I also shoot stills and we always shot during production for marketing materials, the website, posters, etc. The idea to use stills within the film didn't come until late in the process. We didn't settle on using still photos for the transitions until a month before we locked picture. We felt the composition of the photos complemented the sit down interviews and helped tell the story.

You clearly portray Christopher Dennis not simply as someone who performs the part of Superman but as a hardcore fan, someone who actively collects Superman related materials, who hero worships Christopher Reeves, and who shows clear disappointment when he doesn't win the costume competition.

Chris "Superman" Dennis is hardcore. He is obsessive about his character to the nth degree. The others certainly have an affinity for their characters, but not nearly to the extent as Chris. I personally feel Chris has lost himself in his character and I think he would agree. I know his wife Bonnie would agree. He so much want to be a leading actor, he is only known as Hollywood Superman. I think he's afraid of shedding the costume. He has an identity with it and without it he may feel no one will recognize him.

How did you select these particular characters out of the dozens of other performers you suggest are working in this same space? What made these stories stand out against the pack?

It was not a long "casting" process. I thought it would take forever to find the right characters. There are probably 80 people who work on and off on the boulevard and we highlight four of them - Superman, Batman, The Hulk, and Wonder Woman. First, I decided early on to stick with recognizable superheroes. For one, I felt like Superman or Wonder Woman was more iconic and forever then Sponge Bob or Freddie Krueger. Also, I felt that superheroes would make a good metaphor for the lives of the people inside the costumes.

Superman was the first character I approached. He looked like one of the leaders out there. That's how he carried himself. He introduced me to the others. I could have kept "casting." We did have a Spiderman character, played by Spike Henderson. And he was a great character. As opposed to trying to make it as an actor, this ex-professional golfer is trying to qualify for the Senior's Tour. We just didn't get enough footage of him. He didn't allow us enough access into his life to make a full story with an arc, so we had to leave him on the cutting room floor.

The film suggests at places that there is a hierarchy among the performers who work the Strip -- with Superman as a leader of sorts within this community -- as well as some antagonisms between some of the performers. What can you tell us about the community of personalities who interact in this space? Are there, for example, rival Superman performers competing for the same bit of turf or is there an understanding that once a character is taken, newcomers need to assume new roles?

Chris Superman Dennis certainly is the self-proclaimed leader of the boulevard. I don't know if the other characters would agree. But he is probably one of the most knowledegable out there. And he takes the unwritten code of the boulevard seriously. I never witnessed a second Superman but I did see rivals of other characters. Max Batman Allen has had a longstanding rivalry with another Batman character. The two have had many arguments over the years (with police involvement at times). People know what the rules are but don't always follow them so you will see duplicate characters and they compete for tips, argue, and sabatoge one another. This is how these people put food on their tables so someone coming on the boulevard with the same outfit is a problem they must take seriously. It is quite a soap opera out there. I spent two years witnessing it. God, I'm exhausted.