Field Notes from Shanghai: Whatever Happened to Shanghai Swing?

/Shanghai had been a thriving center for jazz and swing music during the 1930s and 1940s. These night clubs are vividly recreated in the opening segments of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom . I got deeper into this world when I had a chance to see some 1930s and 1940s era Chinese musicals when I attended the Hong Kong film festival a decade or so ago. Unlike Hollywood's representation, Shanghai swing was not simply derivative, appropriating western tunes and translating them into a new language. Rather, Shanghai Swing offered a fusion of western syncopation with classical Chinese instruments and sounds. It was, in effect, an early predecessor of today's world music movement. I was able to find a few rare recordings of the 1930s Shanghai Swing, mostly taken from film soundtracks, during a trip to Beijing five years ago and it has a cherished place on my ipod. So, I was determined to learn more about the contemporary swing scene during this trip.

A little research suggests that there are at least some new groups seeking to revive this popular music tradition, much as neo-swing music has enjoyed at least niche success off and on across the western world over the past few decades. I was able to find this website which offers some background on "Yellow Music," as Shanghai Swing was known among some of its followers. They explain:

In the colourful cabarets and sepia-lit dance halls of Old Shanghai, Jazz music set the background score to a fleshy world of mobsters, adventurers, and sing-song girls. Old Shanghai was the uncontested Jazz capital of Asia, where musicians from the World over tested their musical mettle nightly to the delight of enthusiastic audiences. In 1935, Du Yu Sheng, the notorious overlord of Shanghai's ominous "Green Gang" ordered into creation the first all-Chinese jazz group, called "The Clear Wind Dance Band", to perform at the Yangtze River Hotel Dance Hall. Critics called this music 'pornographic,' but the band played on just the same. The wheels of time brought Shanghai's heady heyday to an end as the once-bustling nightclubs were boarded up or converted into Communist factory buildings, and Jazz music was outlawed as an 'indecent' form of entertainment...Until Now.

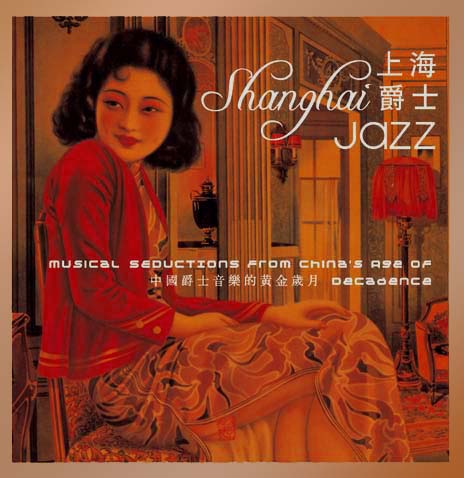

This site publicizes the efforts of the Yellow Music Ensemble to revive his rich cultural tradition, through a series of albums which promise us "musical seductions from China’s Age of Decedence," a phrase which turns decades of anti-jazz criticisms among Chinese cultural and political leaders on its head, even as it continues to exploit western orientalist fantasies about musical exotica from the East. In explaining their name, the site suggests,

The term 'yellow music' was used as early as 1926 by May 4th musical reformers condemning the works of composer Li Jun Hui, labeling them as 'fleshy', 'pornographic' and 'decadent'. Fusing Chinese folk melodies with western jazz and the styles of such composers as George Gershwin seems innocent enough, but having them performed by rows of teenage girls 'clad in costumes that left their arms and legs unencumbered' , drew its' critics . This yellowness to which the authorities objected was not so much the exposed skin color or even the urban pentatonic quality of the music, but its' Chinese-ness, and perhaps its' blackness as well. During the 1920s jazz was racialized and assigned to the lowest rungs of the musical evolutionary ladder, the Shanghai Conservatory considered jazz to be 'a bad form of Western music' much the same manner as were Chinese folk tunes; 'primitive music composed with a pentatonic scale'. This is obviously not the case in the 21st century. We have revived this concept in describing the modern instrumental fusion of Chinese and Western musical styles.

The group has produced three albums so far, which don't seem to be for sale on the site. I have friends in China trying to track down copies for me. The site does offer some mp3 samples as well as an interesting video showing Shanghai Swing then and now. The design of the album covers evoke the aesthetics of old Chinese calendar art, a popular collectible among western visitors to this country, though I suspect few of them connect these amber images of beautiful women in traditional garb back to the thriving entertainment industry in Shanghai during the pre-war years