OSCARS WATCH 2024 — 'The Holdovers': A Crash Course on Using Vintage Sensibilities the Right Way

/This post is part of a series of critical responses to the films nominated for Best Picture at the 96th Academy Awards.

“We may be through with the past, but the past is not through with us!” –Quiz Kid Donnie Smith, Magnolia (Anderson, 1999)

It is unbelievably easy for a film to come across as corny when attempting to put on the vintage aesthetic—also known in some fan circles as nostalgiacore. Frankly, some audiences seem to be getting tired of the nostalgia aesthetic entirely. The term “nostalgia bait” has even been coined in recent years to signify works of new media that maraud retro sensibilities for the sheer sake of suckering audiences into a hollow experience. I have personally become accustomed to viewing vintage-looking films through an extra critical lens, quickly searching for a purposeful reason as to why the film chose its specific aesthetic.

As frustrating and soulless as instances of nostalgia bait are, films that pull off the vintage look with purpose have the potential to be something quite special. Some notable examples from the past decade that come to mind include The Love Witch (Biller, 2016), Licorice Pizza (Anderson, 2021), and Everybody Wants Some!! (Linklater, 2016). The iteration I can never seem to get out of my head is Charlotte Wells’ melancholic, introspective debut, Aftersun (2021). The film follows a young Scottish girl, Sophie (Frankie Corrio) and her father’s (Paul Mescal) Turkish beach vacation. Interspersed throughout the sun-soaked relaxation, mocktails, and Tai Chi are interludes of home video footage shot on a Panasonic camcorder from the 90s. As the film progresses, we learn that we are in fact seeing the vacation not simply from Sophie’s perspective as a child, but rather from her perspective as an adult reflecting upon her relationship with her now estranged father. The choice to shoot select scenes with an early digital look clicks into place after this realization. The nebulous, fleeting memories of our youth ought to be presented the same way we captured them: with a camcorder you’ll likely find in your basement the next time you move to a new city. How we remember is inextricably tied to what we remember. Aftersun is a perfect example of the nostalgic aesthetic executed with an impactful purpose.

image 1

Alexander Payne’s new witty coming-of-age drama, The Holdovers (2023), serves as a crash course in how to answer the crucial question every nostalgically aestheticized film must be asked: what’s the point?

The Holdovers follows three members of Barton Academy, a prestigious all-boys boarding school in New England, as they embark on a frigid journey to hold down the school during the Christmas break of 1970. Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa) is a snarky, yet intelligent student whose mom and stepdad canceled his family vacation to indulge in a delayed honeymoon. Paul Hunham (Paul Giamatti) is the stringent, pretentious history teacher who is tasked with the responsibility of chaperoning the students holding over at Barton until the next semester. Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) is Barton’s selfless cafeteria manager, who decides to stay at Barton to show respect to her son Curtis—a past Barton boy—who was recently killed while fighting in the Vietnam War. The trio are left to their own devices when the family of Barton’s star quarterback helicopters him and the other holdovers, except Tully, to Vermont for a ski trip.

image 2

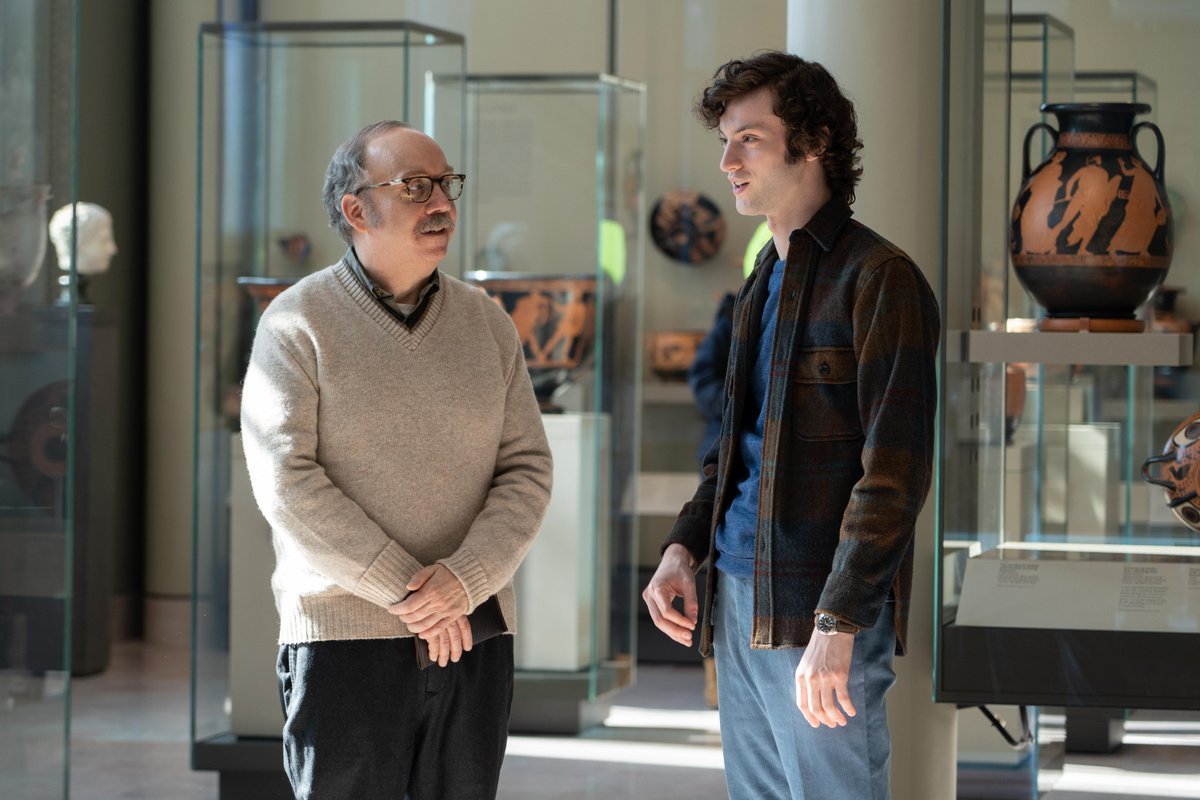

The cigarettes, hairstyles, Miller High Life, audio pops, and film grain all enhance the early 70s setting that Angus, Paul, and Mary inhabit. Apart from its opening scenes with large ensemble casts, someone viewing The Holdovers in theaters might mistake the film for a repertory screening. While this aesthetic throwback creates an exciting audiovisual experience, the technique is far more than a nostalgic gimmick. Just as integral to the aesthetic as the film’s setting is its thematic emphasis on the past; specifically, what studying the past can teach us about the present. The key to this reading of the film can be found scattered throughout but most strongly when Paul takes Angus to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, mentioning:

There’s nothing new in human experience, Mr. Tully. Each generation thinks it invented debauchery or suffering or rebellion, but man’s every impulse and appetite from the disgusting to the sublime is on display right here all around you. So, before you dismiss something as boring or irrelevant, remember, if you truly want to understand the present or yourself, you must begin with the past. You see, history is not simply the study of the past, it is an explanation of the present.

Not only an encouragingly biased PSA on the importance of studying the Peloponnesian War, this assessment from Hunham reveals The Holdovers’ most prevalent argument as well as the justification for its stylistic sensibilities. Like Aftersun, The Holdovers steps beyond aesthetics for the sake of nostalgia and world-building, instead demonstrating a concrete thematic cornerstone for the use of its vintage, 70s look. We can further investigate the film’s purposeful retrospection by digging deeper into the individual arcs of Paul Hunham, Angus Tully, and Mary Lamb as The Holdovers progresses.

image 3

During his time chaperoning Angus and watching television with Mary, Paul Hunham is forced to reckon with his own past. As he and Angus diverge on a trip to Boston, the two cross paths with Hunham’s old classmate from Harvard, revealing the truth that Paul was kicked out of college one semester before graduation. This revelation provides Angus with new insights into the present situation of his crotchety old history teacher. Beyond this very direct confrontation with his past, Hunham vicariously faces his past self through his many similarities with Angus. He and Tully share the same anti-depressants, exhibit the same snarky wit, and dealt with similar hardships in their adolescence. Angus Tully represents Paul Hunham’s own experience as a Barton boy, and he sees what awaits at the end of the tunnel if Tully isn’t given the proper guidance. As the film nears its end and Hunham sticks his neck out to save Tully’s enrollment at Barton, we can read the action as him saving his past self from falling short of his potential. Thinking of this in a different light—Paul Hunham represents the past and Angus Tully represents the present. Now more than ever, Angus needs Paul as a guiding light to understand himself. This idea is reinforced with a conversation Paul has with Miss Lydia Crane (Carrie Preston) at her Christmas party:

Paul Hunham: I guess I thought I could make a difference. I mean, I used to think I could prepare them for the world even a little. Provide standards and grounding like Dr. Greene always drilled into us, but, uh, the world doesn’t make sense anymore. I mean, it’s on fire. The rich don’t give a shit. Poor kids are cannon fodder. Integrity is a punch line. Trust is just a name on a bank.

Lydia Crane: Well… look, if that’s all true, then now is when they most need someone like you.

This interaction highlights the importance of the past informing the present in multiple ways. Not only does it illuminate Tully’s need for guidance, but it also underscores the similarities our present moment shares with the 70s. Wealth inequality, mistrust in government, and political division are undeniably prevalent, but they are by no means novel to the present. Issues of the 70s in many ways mirror those that we still struggle with to this day. To understand our current situation, we ought to investigate the past; as Paul said, our generation did not invent debauchery or suffering or rebellion.

Although Angus Tully is far younger than Paul Hunham, he faces his past with an excursion to the mental institution his father currently inhabits. Tully earlier alluded to the fact that his father is dead, but as he and Hunham make their trip to Boston, we learn that his father is still alive and suffers from paranoid schizophrenia. Angus deeply misses his father, but the visit reinforces the fear that he is doomed to that same fate. Angus expresses this debilitating push and pull of emotions following his visit, and Hunham assures Tully that he is not bound by fate to become his father. Rather, Paul reassures Angus in the fact that he is not only smart and capable but is still only a kid. In what is clearly an incredibly formative moment for Angus, Hunham states that, “In real life, history does not have to dictate your destiny.” While the film harks on the importance of learning from the past, this key distinction is crucial. The past informs the present through our interactions with it. Tully’s confrontation with his father and his subsequent unpacking of that confrontation is what directs his present self. With Hunham’s guidance, Tully learns to reflect on his relationship and similarities with his dad in a constructive manner, gaining a greater understanding of his background while also becoming more secure in his individuality and capability as a young man.

Mary’s journey with her past lies with her son’s death in Vietnam. In an early conversation with Paul, Mary mentions that she couldn’t afford sending Curtis to Swarthmore, even with financial aid. His lack of college enrollment led to his deployment to Vietnam, about which he optimistically exclaimed that he’d be able to attend college with the G.I. Bill upon his return. Mary’s heartbreaking grief is featured throughout the film, as she reflects on Curtis’s favorite music and laments the fact that neither he nor his father made it past 25 years old. At first, Mary feels the need to stay in Boston rather than visit her sister, Peggy (Juanita Pearl), in Roxbury. As Mary grieves her son’s loss and reflects upon the past, she changes her mind and visits Peggy, bringing Christmas gifts for her soon-to-be baby. We later find out that Mary plans to continue working at Barton with the intent of helping Peggy’s future child afford college. As emotionally challenging as Mary’s reflection on the past may have been, she ultimately allowed her pain to positively instruct her present actions.

image 4

Along with its characters reckoning with their past to understand the present, The Holdovers pays its respects to many of the films that came before it. The most obvious homage here is to Wes Anderson’s Rushmore (1998), not only in song choice but also in character dynamic, camera movement, and setting—one could easily picture Paul Hunham teaching a course on the French Revolution at Rushmore Academy. The film’s formal elements also strongly resemble the crash zooms of Mike Nichol’s classics, most notably The Graduate (1967). The coalescence of these character arcs, homages, and vintage aesthetic all point to the idea that there may be more to learn from the past than we think. From modern sociopolitical happenings to filmic technique to personal and emotional development, The Holdovers teaches us the importance of studying the past to understand the present.

Biography

Matt Severino is a master’s student in Media and Cinema Studies at DePaul University (Chicago, IL). His main research interests pertain to death confrontation in film, but he has also written work on the visual representations of toxicity in films like Erin Brockovich and Silkwood. Alongside his academic pursuits, Matt is actively involved in Chicago’s cinema scene, helping program and market for Facets Cinema and the Chicago International Film Festival.