We Witnessed One of the Best FIFA World Cups Ever Played on the Graves of Thousands of Migrant Workers… What Now?

/The following post was created as part of the assigned work for Henry Jenkins's PhD seminar, Public Intellectuals. The goal of the class is to help communication and media studies students to develop the skills and conceptual framework necessary to do more public-facing work. They learn how to write op-eds, blog posts, interviews, podcasts, and dialogic writing and consider examples of contemporary and historic public intellectuals from around the world. The definition of public intellectuals goes beyond a celebrity-focus approach to think about all of the work which gets done to engage publics -- at all scales -- with scholarship and critiques concerning the media, politics, and everyday life. Our assumption is that most scholars and many nonscholars do work which informs the public sphere, whether it is speaking on national television or to a local PTA meeting.

On December 18, 2022, approximately one out of every five human beings on Earth watched Lionel Messi lift the World Cup for Argentina in Qatar. What seemed like the pinnacle of everything sports, culture, politics, entertainment, and humanity was reached when Gonzalo Montiel neatly tucked in that 4th Argentina penalty to the right of French captain and goalkeeper, Hugo Lloris. What still replays in my mind, as well for millions of others, is iconic Argentinian American sports commentator, Andres Cantor, calling the game live in Spanish for Telemundo as that final penalty went in, “GOOOOOOLLLLLLLL! ARGENTINA CAMPEÓN DEL MUNDO! ARGENTINA CAMPEÓN DEL MUNDO!” as he smiled and cried on live air.

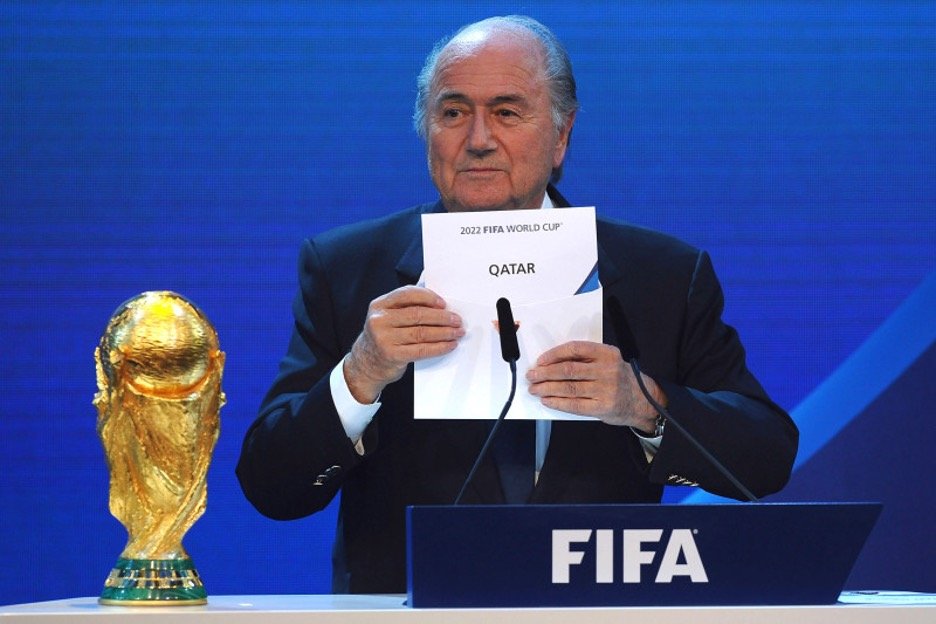

Now rewind 12 years to December 2, 2010, when FIFA announced a shock when Qatar - a small Arab Gulf nation that wasn’t too well known on the world stage and had almost no football/soccer history - was awarded the bid for the 2022 FIFA Men’s World Cup, beating out the likes of England and the United States. FIFA’s decision clearly set off alarms concerning suspicions of corruption and bribery. Out of the eight stadiums that were to host World Cup matches, seven of them were not even built yet. The country was in no shape to host the largest sporting event in the world, and so a 12-year rapid growth project ensued.

Laurence Griffiths/Getty Images

Quickly, it became clear that this project was fueled by migrant laborers (mostly from South Asia) under a strict labor system called the Kafala. Pete Pattison came out with a groundbreaking exposé on how Qatar was essentially operating under labor conditions that many referred to as modern day slavery. Migrant workers in extremely economically precarious situations were essentially exported by contracting agencies in their home countries under misleading employment terms and (in many cases) worked to death. Nepali migrant workers made up a disproportionately high number of Qatar’s workforce in the last decade, listed as the second most populous group in the country (even ahead of Qatari nationals). The majority of Qatar’s population is composed of migrant workers, with most of them coming from South Asian countries.

While the exact number is disputed, over 6,500 workers were killed by the time the kickoff whistle blew for the opening Qatar vs. Ecuador match. Many people were aware of these conditions around this 2022 FIFA World Cup, yet so many didn’t know what to do about it. Ultimately over $200 billion was spent with an estimated revenue of only around $10 billion. Certain Western countries such as Denmark and Germany tried to engage in subtle and non-disruptive protests such as posing in the starting XI lineup with their mouths covered, yet drew backlash as the team and federation turned a blind eye when German star Mesut Ozil spoke about the racism he experienced for his Muslim faith and Turkish background. A number of European captains planned to wear rainbow-colored armbands as a protest to the anti-Gay laws in Qatar, but swiftly backed out when FIFA officials threatened them with yellow cards as punishment.

Alexander Hassenstein/Getty Images

When asked about the number of deaths, Qatari officials acknowledged that there were three deaths in the buildup to the World Cup, but eventually said there were between 400-500 when pressed further, which is a still a gross underestimate of the lives of migrant workers lost in Qatar.

As part of my undergraduate thesis, I travelled to Nepal to conduct ethnographic work and interviews with these migrant workers who were in the process of obtaining visas for migrant labor to Gulf Countries and those who had returned from working in these places. As if reading about all these atrocities and watching several expose documentaries was not disheartening enough, talking to these people who were vulnerable (and in many ways manipulated), I felt like I wanted to do something about it besides studying what was really going on behind the scenes. Awareness doesn’t do too much when you’re dealing with arguably the single largest collectively shared, simultaneous human experience - the FIFA World Cup with its hundreds of billions of dollars in capital investment.

I found that the operation of migrant labor for these types of global mega-events were rooted much deeper than they seem. Especially in economies that were vulnerable and malleable, the geopolitics of exporting labor were a significant portion of ensuring a growing economy at the cost of the lives of those at the bottom of the socio-economic hierarchy. Approximately 1/3 of Nepal’s GDP is remittances - money that gets sent back home by Nepali workers abroad. This meant that the hundreds of thousands of workers going abroad (and thousands of them dying) were not a coincidence but part of an oiled machine. Airlines, healthcare companies, banks, and a number of other industries all relied on the exportation of migrant workers to operate and make a profit. Returning from my travels at the Kathmandu airport, I really got a glimpse of how important the labor exportation economy was. There were three designated lines at the exit visa area: 1. Nepali nationals, 2. Foreign Nationals, 3. Migrant workers. I had never seen that third designation at any airport I had been to; to put in perspective, that migrant worker line was by far the longest line whereas the other two were practically empty.

Picture by Pratik Nyaupane

The profit, however, meant that these workers (mostly young men from impoverished families and very low education and literacy rates) would arrive in foreign countries such as Qatar to have their passports confiscated, pay withheld, and forced to live and work in unsafe and unsanitary conditions. As I talked to many of these workers, they were simply trapped in this inhumane operation, not just by their employers, but by the governments and agencies designated to support them.

Sam Tarling/Corbis via Getty Images

But there is also no denying that to many like me, the FIFA World Cup is the ultimate form of emotion, family, and connection. I spent hours each day watching every minute of every match for a month. My phone was blowing up with notifications in the half a dozen group chats I was in alongside several other friends who were texting me about every goal, controversial play, and nail-biting moment. Almost everyone who has watched soccer in the last 30 years has grown up watching Lionel Messi play and cementing his stature as one of the greatest athletes to have lived, winning every trophy eligible besides the most difficult one of them all - the World Cup. I found myself singing Argentinian chants while standing in line at the store while witnessing videos of hundreds of thousands of people in every corner of the world, such as those in Bangladesh (a country that also exported thousands of laborers to Qatar), stay up until 4 am to watch Argentina’s historic run.

For every soccer fan and Argentinian, this World Cup will be a moment they will never forget. Millions of people in Buenos Aires flocked to the streets at the same time as thousands filled Times Square and other town squares across the world to celebrate. My grandmother in Nepal told me she couldn’t sleep because people were shooting off fireworks all night with excitement over Argentina’s first world cup victory in 36 years. Clearly the passion of the sport of world football takes over the world. FIFA has claimed that approximately 5 billion people engaged with the 2022 World Cup, whether it be watching a match or engaging with social media content.

It has now been over two months since the World Cup ended, and we are forced to ask the question: were those moments of joy worth the thousands of deaths of workers and the abuse and trauma of hundreds of thousands more? Obviously, not.

The geopolitical and economic power of sporting governing institutions such as FIFA and the International Olympic Committee are expanding more and more. I argue that these are full governmental bodies themselves and harness enough power to override the sovereignty of many nations and human rights of billions. It has been evident that with the joy surrounding football can be used for good, however these organizations are able to act recklessly without oversight and accountability for their own profit and power.

The FIFA Women’s World Cup is less than 150 days away, and the next men’s tournament is being hosted in the US, Canada, and Mexico in 2026. I do believe that sports can be enjoyed by the masses without there being violent harm, displacement, labor exploitation, and death, but the playing field is uneven with institutional and political power on the sides of those who merely seek profit. I don’t know the simple answer. But what I do know is that there are already a number of human rights, labor rights, migrant rights, and other advocacy groups that have been relentlessly fighting against the harm that these events cause. Now, it really is abilities as individuals to engage through collective action to hold officials and bad actors (who are greenlighting these detrimental operations) accountable to ensure that that we can prevent these grave injustices from occurring in the future.

Biography

Pratik Nyaupane is a Ph.D. student at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California, where he broadly looks at the intersection between society, technology, and politics. He arrived at USC with a Bachelor of Science in Informatics and a minor in Political Science from Arizona State University, where he conducted his thesis exploring the plight of Nepali migrant workers in Qatar in the development of the 2022 FIFA Men’s world cup. As a doctoral researcher, Nyaupane has been exploring the ways in which technology is used as a form of state and private power. His most recent projects consist of evaluating policing and surveillance technologies on university campuses, sports stadiums, and national citizenship registries. His academic work can be found in the International Journal of Sport Communication and Big Data & Society.