Global Fandom Jamboree Conversation: Katty Alhayek (Syria), Julie Escurignan (France) and Irma Hirsjärvi (Finland) (Part Two)

/Julie Escurignan

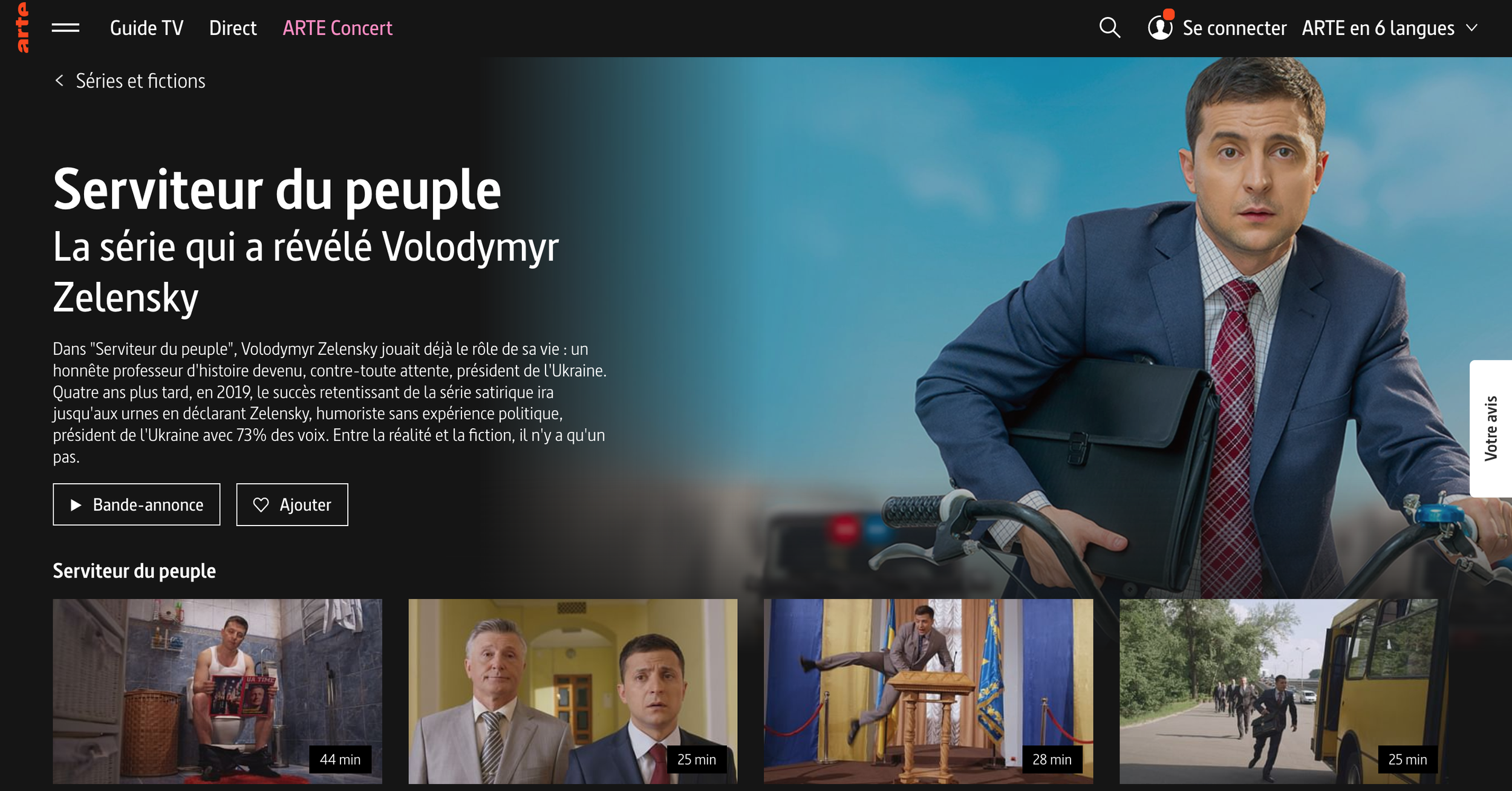

Katty’s research sample is one I had never thought about before: the Syrian fans of Game of Thrones, a population faced with war and displacement. Katty writes: “when we think about the Syrian war and subsequent refugee crisis, currently the largest displacement crisis in the world (UNHCR, 2021), we don’t tend to imagine these displaced populations as fans and active audiences of entertainment”. She raises here a very interesting, and, in my opinion, important point. We tend to think about fans as people living in an environment ‘allowing’ them to have the time and resources to be fans. But what about fans who end up in war situations? Do they stop being fans? Do they keep being fans? Katty underlines how these populations, despite facing difficulties, do not give up on their fandoms, and on the contrary, rely on them in dire times. To me, this echoes what is currently going on in Ukraine on more than one level. Similarly to Syria, there are of course in Ukraine fan populations facing war and displacement. But there is another layer added to it from our point of view as Fan Studies researchers: the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, is himself a figure from the entertainment world. Zelensky was an actor who played the role of an Ukrainian president on a television series, and one of his current advisors is one of this show’s screenwriters: the fiction has here fully entered the political realm, and fans of the actor and the show are now facing this almost dystopian situation of being fans of both a former actor and a current political leader in times of war. Katty’s piece had me thinking about the links between fandom, politics and war, from Syria to Ukraine (with their own specificities of course; I do not mean that both situations are the same and questions of culture, religion and links toward Western countries are obviously different). I believe there is a fascinating research topic going on with the Ukrainian war and its political leader. How are fans of Zelensky-the actor reacting to Zelensky-the war leader? And how is Zelensky’s image as a ‘war hero’, as Western media name him, impacting his actor’s image and his fandom? In France, the German-French channel Arte is currently broadcasting the series Servant of the People (Слуга народу) starring Volodymyr Zelensky, with a raising interest from French audiences (1.8 million viewers for the show on March 7th according to the media Le Parisien). Zelensky’s image as a war leader facing on the Russian forces is attracting audiences toward its previous work as an actor. Will this genre transfer lead up to the creation of new fan communities? Will these fans be fans of Zelensky-the actor, Zelensky-the political leader, or any mix of both? And will European or international fans of Zelensky be similar or different from Ukrainian fans of Zelensky, fans who actually experience his political leadership and the current war? Only a deep dive into this project and time to see how the war will evolve could bring us answers, but there are issues of fandom, war and politics at stake in Ukraine as there were in Syria. In that regard, I think Katty Alhayek’s work is leading the way toward new research on the relationship between fan communities, political expression and war situations.

The original Game of Thrones poster layout has been used by international politics."

Donald Trump used Game of Thrones layout in his political message “Winter is coming.” to Commander in chief Qasem Suleimani of Iraq, who published his response by using the same font of letters: “I will stand against you”

Irma Hirsjärvi

Is fandom about building a future?

I come home, exhausted, my heart broken. I cannot cry. The memories of my friends - young somalian kids fleeing the civil war, and again new refugees in 2015, the fall of Afghanistan just months ago, all the memories wake. The pressure, the agony.

And now Ukraine.

Volunteers organise again, overnight, all over my country to welcome new people. Three weeks have already gone, and the Russian attack on Ukraine keeps pushing millions from their homes, over borders around the globe. Finland prepares for 10 000, 40 000, 100 000 refugees. Money is not a problem. Not equipment, not food, not medicine. We have plenty. The problem is to follow all this brutality, the destruction of lives, dreams and the future of children.

I just sit there. I cannot speak. My husband who works at home glances at me over his home office. He does not say anything. After a brief moment he puts his laptop aside and opens the TV, selecting the programme. He is a gentle man, but now he speaks more softly than ever: “You think it would be the time to see this?”

On the screen is a text: “Servant of the people”. It is a Hungarian tv-series, broadcasting now also in Finnish National TV, starring the well known present-day president, the war hero and already a legend, previous comedian and actor Volodymyr Zelensky. I know the series, but watching it just now feels totally impossible.

“ I do not know if I can watch him.”

He does not reply, but presses the button, and soon we see the view of Kiev, and the “three witches”, the oligarchs of Ukraine giving the opening lines for the series. I sigh, and cry a bit.

Finally we end up watching the first seven 40 minute periods in a row. It is a sharp, dark comedy. Almost five hours of TV-marathon skillful political satire about a deeply corrupted nation and its strong Russian ties. As we watch, we walk in the streets of Ukraine and into homes and palaces of a beautiful country, where a humble and honest history teacher is elected, accidentally, as a president. I realise that even if I cannot tie any emotional strings to ‘Zelensky the president’, for this war and all death and suffering are real, I can love ‘Zelensky the actor’, and admire his quite obvious political plan. In a strange way it helps. It makes me stronger.

---

When I read Julie Escurignans response, where he pondered about the reception and fandom of the entertainer Volodymyr Zelensky in different parts of the world, it immediately took me back to that evening of only two weeks ago, where I learned to know ‘Zelensky the actor’. The TV-series is not only entertainment, but a cross-section of Ukraine, a mighty lesson of its political corruption, democracy and overall state economy. Furthermore, the “Servant of the people” is a political programme that teaches Ukranians about the different kinds of reality, utopia, even.

The TV-series and movie, along the other active career of his as an entertainer, created a media fandom of Zelensky. In Servant of the people Zelensky was seen as a righteously, independent, witty and lovable character. That fandom, created by the TV-series broadcast the first time in 2015 and its sequel movie next year allowed him to win a presidential election of Ukraine in real life, three years later. That was a surprise, but not an accident. The TV-series and a movie created a political utopia, and the words for it to come true.

Fandom has been noted in a political realm to be useful in many ways. As Tanja Välisalo (Välisalo & Hirsjärvi 2022) notes, the iconic fantasy memes and themes have been harnessed to political tools, even in top level international politics. The president of the USA (2009-2017), Barack Obama used in his campaigns popular culture and in the office references to the popular texts to create connection to people, and to sound cool. With success. Donald Trump tried the same method, when he sent a tweet with his picture and a text “Sanctions are coming” written in Game of Thrones font (printed in New Yorker 2.11.2018). The text referred to the sanctions of the USA against Iran, but the visual appearance and words came from the Game of Thrones slogan “Winter is coming.” This was answered by general and Commander in chief Qasem Suleimani, who published his response by using the same font of letters: “I will stand against you” 3.11.2018. (Välisalo & Hirsjärvi 2022, 326-329)

After the first phase of fandom research (fandom as a pathological psychic and/or social disorder; Jenson 1992), the second phase (understanding the meaning making process and resistance nature of fandom; Jenkins 1992, Bacon-Smith 1992) and the third phase (becoming a legitimate research field; Fiske 1992, McGuigan 1992/2003) one can claim that we have moved into fourth phase of fandom research, a time of political fandom research. Fandom is even more than identity issues or meaning making process as such. It is also the form of global talk, creating free zones over cultural borders and language barriers. Furthermore, fandom has also become meta-language: and as such it is part of cosmopolitical power negotiations in the global mediasphere, suggests Tanja Välisalo. Along with other media, there is also a true need to explore deeply global on-line games from this perspective (Koistinen, Koskimaa & Välisalo, 2021), as fantasy is an international language, it is deeply political, and its fandom is aware of meaning making processes.

And meaning making is at the core of politics. There are continuous powerful movements and demonstrations for Ukrainian people and against Russian warmongering without weapons, only by using symbolic expressions and pictures in colours and lights of blue and yellow around the globe, demonstrations, memes and constant flow of pictures of Zeletny in all social media.The refer constantly to popular culture phenomena, that are globally common and dear to us. For me it’s as if in the centre of all this there is a small figure of Zelensky, a common person, everyman, a nice teacher from a TV-series, reminding me little Frodo Hobbit from the Lord of the Rings of J.R.R. Tolkien, with his impossible task ahead.

For this reason I see Katty Alhayek’s study as extremely important. Syria has suffered massive destruction. Building the future starts from imagination, having an utopia, giving names to things we do not have now, creating a joint language to talk about the shared meanings and tasks.

—-

Bacon-Smith, Camille (1992) Enterprising women. Television fandom and the creation of popular myth. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvanian Press.

Fiske, John (1987) Reading the popular. LOndon: Routledge.

Hirsjärvi, Iirma & Välisalo, Tanja (2022) Fantastinen fanius. In Jyrki KOrpua, Irma Hirsjärvi, Urpo Kovala, Tanja Välisalo (eds.) Fantasia. Lajit, ilmi ja yhteiskunta. Jyväskylä: Research Centre for Contemporary Culture. 313 - 329.

Jenkins, Henry (1992) Textual poachers. Television fans and participatory culture. London: Routledge.

McGuigan, JIm (1992/2003) Cultural Populism. London: Taylor & Francis e-Library.

Koistinen, A.-K., Koskimaa, R., & Välisalo, T. (2021). Constructing a Transmedia Universe : The Case of Battlestar Galactica. WiderScreen, Early online. http://widerscreen.fi/numerot/ajankohtaista/constructing-a-transmedia-universe-the-case-of-battlestar-galactica/

Katty Alhayek

By comparing gender dynamics in both Julie’s sample and my sample, I wonder if the difference is a result of sample luck or venue of fandom. Scholars, like Hassler-Forest (2014), who studied HBO strategy of producing “quality TV” shows like Game of Throne argue that HBO aims to attract “a desirable global elite audience” promising its audience, regardless of their actual gender, to change their relationship to television “from ‘passive,’ ‘feminine’ spectatorship to that of an ‘active,’ and therefore ‘masculine,’ connoisseur” (p. 166). In Arabic online spaces, I found most fans identified as male. Similarly, in English online spaces, around 82% of the English-speaking fans are male according to demographic survey results by The ASOAIF Crypts in 2017. However, in my personal experiences with fans in Western Massachusetts, the place where I lived during the show run, I noticed the popularity of the show among men, women, and LGBTQI+. So I wonder if the visibility of male voices in the English and Arabic speaking fan pages of Game of Thrones I observe relate to the issue of traditional male voices’ dominance online in non feminist fan and gaming spaces.

I agree with Irma’s statement that a phase of political fandom research is unfolding with TV stars like Volodymyr Zelensky (and Trump before him) building political careers by capitalizing on the support of their TV fan base. As Julie noted there are similarities to be explored between Syria and Ukraine in relation to fandom and politics. The brand of Prestige TV—like Game of Thrones and the upcoming prequel, House of the Dragon—is based on the promise of providing audiences with the opportunity to explore intellectual questions of struggle over political, social, and personal power. I am interested in observing emerging comparisons between the heartbreaking real-world political events of war and displacement in Ukraine and fantasy drama TV shows. How such comparisons relate to fans’ perceptions and interpretations. I think this will be an interesting area of research to explore questions of fandom, race, and solidarity.

References

Hassler-Forest, D. (2014). Game of Thrones: Quality television and the cultural logic of gentrification. TV/Series, (6), 160‒170.

The ASOAIF Crypts. (2017, January 10). The ASOIAF/GoT demographic survey results [Web log post]. Retrieved from https://atimecapsuleoficeandfire.wordpress.com/2017/01/10/the-asoiafgot- survey-results/