Global Fandom Jamboree Conversation: Mado Mai (Cameroon) and Anastasia Rossinskaya (Russia) (Part Two)

/М: Your responses are quite enriching and seem to focus mostly on different modes of communication with the example of ficwriting and how each mode of communication can be used to enrich teaching and learning nowadays. It however appears that there are more facets of communication than what you have mentioned directly. Can you maybe expand more on the SKAM/DRUCK TV shows clearly illustrating the impact of the fans on such shows?

A: I will do that with great pleasure. Recently I analyzed the structure of communication between creators and fans of DRUCK, a German remake of a Norwegian TV show SKAM. The original show was based on thousands of interviews with teenagers that Julie Andem, its screenwriter and director, conducted around Norway (Pickard, 2016). Thus the original show was conceived as a result of intense communication with the target audience.

When different countries started making their remakes of SKAM, adapting it to their cultures, it wasn’t supposed that viewers would have much influence on the content. The first seasons of SKAM France, SKAM Italia, SKAM NL, WTFock (a Belgian remake) closely followed the plotlines set by SKAM. However, in February 2018, after the German remake was announced, a German fan made a post on Instagram (see Pic.1) suggesting that the third season of the German remake should be about a transgender character. This suggestion was supported by many viewers and though this character was not in the original show, DRUCK creators managed to persuade the broadcaster to include them. David Schreibner, the first trans character in SKAM universe, became one of the main characters in Season 3.

Pic 1. The screenshot of the post that started the campaign for transgender character in DRUCK (posted on February 20, 2018 https://www.instagram.com/p/BfbXkkyBDZE/)

When creating their own further seasons 5-7 (2020-2021), the authors of DRUCK were not constrained by the limits of the original SKAM material. To find relevant themes and stories, they asked their audience – teenagers and young adults in Germany to fill out questionnaires about their lifestyles, problems, friendship and love, graduation, etc. They were distributed through the official DRUCK channels on YouTube and Telegram. According to reports on the official DRUCK Telegram channel @DruckDieSerieBot more than 20 thousand people responded to the questionnaire for the new generation in early 2020, and 27281 people responded to the next questionnaire in early 2021. The creators of the series carefully analyzed viewers’ responses and used some plot ideas as well as problems and concerns fans wrote about in the script. We see here an example of how media creators can engage audiences into co-writing the show through direct and indirect communication.

The dialogue between viewers and show creators is most intense while the show is airing. Due to the transmedia format of DRUCK, which includes short clips on YouTube, the characters' WhatsApp chats and Instagram accounts, viewers have the opportunity to engage in active communication with the creators and even characters in real-time. On the official channel it is done through comments, which often get replies from a representative of DRUCK (Pic. 2). In comments fans discuss events happened in clips, share impressions, opinions and life experiences. During the episodes live broadcast each Friday, viewers can communicate with each other and with a DRUCK representative in a live chat. In this case, an exchange of emotions prevails. Thus, viewers can give feedback to creators directly as they are watching, and creators who are present in the chat too can observe the impact that an episode makes.

Pic 2. Viewers’ comments and DRUCK’s replies to Clip 28 of Season DRUCK Nora on YouTube https://youtu.be/6Du8s3Z73D8

Another channel of communication is the platform where viewers receive screenshots of the characters' chats. It changed several times, depending on which platform was more convenient for the dialogue with the viewers at that moment. At the beginning of the first season in March 2018, Tumblr (druck-serie-blog.tumblr.com) was used for this purpose, then WhatsApp. In September 2019, the channel moved to Telegram, and in September 2021 to Instagram. On each of these platforms, viewers could send messages to DRUCK, but the intensity and engagement in communication varied. The dialogue was especially intense on Telegram. Viewers received detailed personal responses to their messages from DRUCK representatives. Moreover, fans who did not know German received replies in English.

It is interesting to note that the choice of the social network can lead to a breakdown in communication with viewers. Before Season 7 Isi, DRUCK obtained an official Instagram account @druckaddicts. During the season it was used to post characters’ chats in stories, to announce episodes’ airing times, to post memes, videos from clips, screenshots, polls, etc. However, some viewers reacted negatively to this innovation. Co-existence of the official account and characters’ accounts on the same platform ruined the participatory and realism effects for them.

There is a lot of interaction among fans when the show is airing. It mostly takes place on Tumblr, Twitter and Instagram. Viewers make posts to express their opinions and emotions in the form of text posts, screenshots, gifs, fanart and fanfiction. Posts are commented on by other fans and discussed in fan chats. "Reaction" format is also popular: video bloggers record themselves as they are watching episodes and reacting to them. Since most of the viewer content is posted publicly, DRUCK creators can see it using their private accounts. In interviews, they say that they follow viewers' posts on social media and, although they do not engage in direct communication, they discuss viewers' opinions in the course of their work (see for e.g., Barwenczik, 2019). The only exception from this rule that I know of is the writers' reaction to Ana Pinto's YouTube video reactions to Season 6. DRUCK Team praised her in stories in their private accounts on Instagram.

During hiatus between seasons, which sometimes lasted as long as 12 months, the dialogue between viewers and DRUCK creators does not stop. Viewers regularly initiate communication using all available means – email, the official Telegram channel and Instagram account, as well as engaging in direct communication with the actors, directors, and screenwriters through their private accounts and during lives on Instagram. New media have made creators more accessible to fans. The local homely nature of DRUCK and the openness of its creators to communication resulted in their multiple conversations with fans.

In my short overview I tried to show various ways communication between TV show creators and viewers can happen. It is important to note that this becomes possible only if the production team is interested in the dialogue and ready to listen to and adapt to their audience.

References

Ana Pinto’s YouTube channel https://www.youtube.com/c/rantyana (accessed: 15.03.2022)

Barwenczik L. (2019) Young Adult Series “Druck”: “A Little Flippant and Imperfect”. Goethe Institut https://www.goethe.de/en/kul/flm/21657771.html (accessed: 15.03.2022)

DRUCK / funk Presse https://presse.funk.net/format/druck/ (accessed: 18.03.2022)

Pickard M. (2016) Norway feels Shame / Drama Quarterly https://dramaquarterly.com/norway-feels-shame (accessed: 15.03.2022)

A: Is it common for Cameroonian hip-hop artists to engage in communication with their fans and followers? How do they use their public image for communicating social messages?

M: Looking at the practices of youth hip hop culture in Cameroon through the lenses of online social media, television and advertisement for instance, it is obvious that this embraces language forms which embody their identities and other cultural artefacts. These hip hop media practices portray identities which are exhibited in forms of dancing, dressing and speech in their musical linguistic repertoires that are not only multifaceted but also complex.

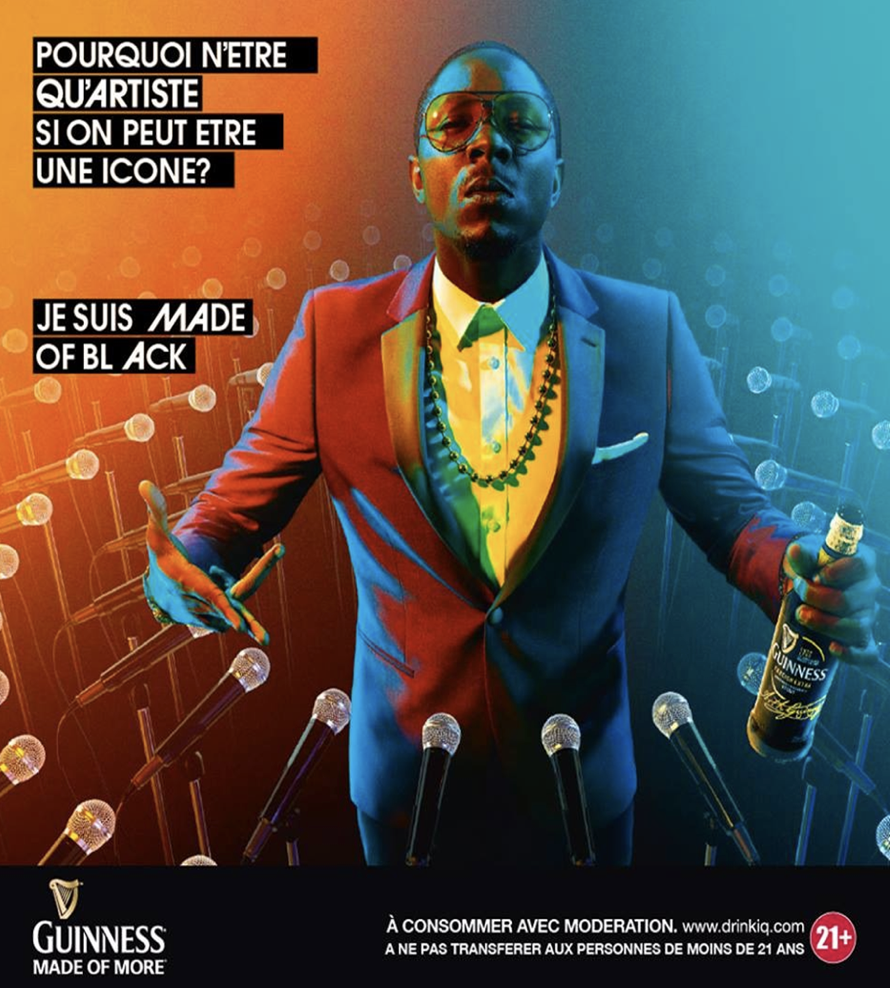

A look at the advertisement billboard with the Cameroonian king kong in Figure 1 below substantiates this claim. That Stanley Enow features in a Guinness advertisement says a lot about the number of his fans and followers and their behavior as well. This time, it is not only limited to the youth. It cuts across generations given that Guinness Cameroon is an ancient enterprise well-known for its identification, selection and rewarding of the very best talents in the country.

Figure 1: Stanley Enow adapted; from Guinness Made of More Large Format Campaign for the Agency AMVOBBDO (https://cargocollective.com/motioncult/Guinness-Made-of-More).

That Stanley Enow features in a Guinness advertisement says a lot about the number of his fans and followers and their behavior as well. This time, it is not only limited to the youth. It cuts across generations given that Guinness Cameroon is an ancient enterprise well-known for its identification, selection In the advertisement above, they recognize the young artist as an iconic figure in society and hence the question “Pourquoi n'être qu’artiste si on peut être un icône? (Why limit oneself to being just an artist if one should rather be an icon?). This also demonstrates in a way that Guinness Cameroon identifies themselves in the young artist and hence, the company in this advertisement suddenly switches from the highly standardized French version and English version (“Guinness Made of More'') to Camfrnglais; “Je Suis Made Of Black”. The blackness of the Guinness beer can also relate to the Africanness of the multi-talented artist

Born in Bamenda, the capital of the Northwest region of Cameroon, with family from Bayangi, located in the Southwest region, Stanley Enow’s nickname “Bayangi Boy '' reflects the importance of regional origins for the young rapper. Coming from the two English-speaking regions of Cameroon (West Cameroon), and having attended school in the Western Region, French-speaking Cameroon, (East Cameroon), Stanley Enow choses to rap in CPE and Camfranglis, as a way to translate his cultural diversity and Cameroonianess in his music.

In June 2013 Enow became famous with his first single “Hein Père'' which again became a center of attraction in the Cameroon 2021 African of Cup Nations finals. The video, with more than a million of views, followed the traditional depiction of young male rappers, with a great display of luxurious cars, jewels, and surrounded by his crew in the background. In the song, Stanley Enow uses a lot of Pidgin English, CPE which is a (re)mix of English and the national languages/expressions (Camfranglai)s – youths’ favorite language for communication (cf. Mai, 2007). His cultural pride and sociolinguistic repertoires do not only appeal to the youths and fans who rally behind him as seen in one of his Facebook interactions with his followers below;

“I would like to thank all of my fans nationwide who have secretly tattooed MOTHERLAND or Stanley Enow in their souls.

I have a VERY STRONG ARMY

LOVE YOU ALL”.

In fact, his communicative style also extends to attract fans from other avenues. Among his followers are the radio stations and popular industries as shown above. His linguistic repertoire is reiterated in the above advertisement which displays English, French and Franglais, thus, also showing his secret of attraction. The famous age-long Guinness company in Cameroon business owners are thus not insusceptible to his linguistic repertoires.

His language forms, his portrait on the billboard above and the lyrics of his song below translate the same confidence familiar in the hip hop industry and among youths, especially with the title “Hein Père” which is an interjection from Camfranglais, meaning “say what!”, used to express either surprise or admiration. The French word “Père” means “Dad” and in Cameroon it is a way to call a homeboy.

Hein Père lyrics and translation

“I don waka no be small, se ma foot

/I have walked (meaning worked) so hard, look at my feet/

Up down around town see ma boots

/Up down around town, look at my boots

Ma foot dem di worry need Dschang shoes (Shoes made from used tires and plastic, popular among low-class people, useful during rainy days.

/My feet got so bad they need Dschang Shoes

Like Banso man I di fight fo ma oun

/Like a Banso Man I fight to survive/ ( Banso refers to “people of Nso”, a people of the Bamenda Grassfield in the Northwest Region of Cameroon.).

With his “Hein Père” Stanley Enow expressed his attachment for his culture. He put Camfranglais and CPE on the spotlight of the African hip hop scene and social media.

Lyrics of “Hein Père”: https://genius.com/Stanley-enow-hein-pere-lyrics

Music video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rcc2dAkaOcY

Reference List

Agha, A. 2007. Language and Social Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bird, S. 2001. Orthography and Identity in Cameroon. University of Pennyslvania: [online]; Available, http://sabinet.library.ingentaconnect.com/content/jbp/wll/2001/00000004/00000 0 02/art00001. Accessed, 03/11/2022.

Harris, T. (2019). Can It Be Bigger Than Hip Hop?: From Global Hip Hop Studies to Hip Hop

Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 6, Iss. 2 [2019], Art. 7

Mai, M. 2007. Assessing Patterns of Language Use and Identity Formation among Cameroonian Migrants in Cape Town. Masters Dissertation, Linguistics Department, University of the Western Cape.

Mbock C. G. (ed.), Cameroun: pluralisme culturel et convivialité (Edition Nouvelle du Sud, Paris, 1996).

Nyamnjoh, Francis B. & Jude Fokwang. 2005. “Entertaining Repression: Music and politics in Postcolonial Cameroon.” African Affairs:245.

Nyamnjoh, F (1999), ‘Cameroon: a country united by ethnic ambition and difference’, African Affairs 98, 390 pp. 101–18.

Tagem, D. (2016). Oral History, Collective Memory and Socio-Political Criticism: A study of popular culture in Cameroon DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/tvl.v.53i1.11 ISSN: 0041-476X E-ISSN: 2309-9070. Tydskrif Vir Letterkunde.