Global Fandom Jamboree Conversation: Yiyi Yin and Susan Noh (Part Two)

/Susan (respond to Yiyi):

Two features of Yiyi Yin’s entry stood out to me: the emergence of fan circles and the continued centralization of algorithmic cultures and digital features which mediate engagement between the fans and their objects of affection, as well as engagement with one another. I believe that “fan-circles” may need further clarification and definition of what it actually is. From the entry, I am presuming that fan circles are fandoms in which boundaries are blurred between various groups. For example, Chinese ACG fans can easily overlap with K-pop fans, as is often the case with the American anime fandom, and it may be safe to assume that one who is literate in anime culture within the United States may also have a fair amount of exposure to K-pop culture as well. It is interesting then to consider how fan morality may overlap with one another, irrespective of one’s object of affection. For example, the general acceptance of fansubs as being necessary within both K-pop culture and anime culture, even in the face of strict piracy laws, may gesture towards this overlap in ethical codes that govern global fandoms. How scholars can go about studying the overlap of international fandom, the moments of contact, and the frictions and symbioses that these moments of contact foster would be very productive.

In the case of K-pop fandom and ACG fandom within China, I would particularly be interested in how historical colonial legacies continue to shape the ethicality of these overlapping fandoms, and whether these histories influence the way Chinese fans engage with these various fandoms. Given the blurring of boundaries between fandoms in China, it would be interesting to see how one’s own historical background may contribute to this blurring. In the American anime fandom, but perhaps more specifically, the music fandom subsection of the anime fandom, there are sometimes discussions and frictions relating to how one should perceive K-pop within this merging of East Asian music fandom. While discussions between fans are tinged with a kind of political ethos that may go unnoticed by the fans themselves, it is fascinating to see how these historical legacies continue to color fan rhetoric.

In regards to using the formal features of platforms to shape fan practices, there was also a key moment of overlap between Yiyi’s research and my own on formal streaming services. Crunchyroll, which is a streaming service that caters primarily to the global anime fandom has a series of platform features which help to define them as a “fans-first” service within the slew of streaming services that originate from the United States. Given the intense competition that they face from more general and mainstream services like Netflix, Amazon Prime, HBO Max, and more, all of which have stakes within anime distribution, it behooves Crunchyroll to really highlight features that foster fannish affect. This includes a five-star review system, forums, comment sections, review sections, news sections, and more. Given the high volume of fan contact that subscribers are privy to, it has been productive to observe the ways in which fans govern themselves within these spaces.

Much like the “report” function that Yiyi gestures to in her own research, fans can be seen occasionally using the “spoiler” function on Crunchyroll’s comments sections, which immediately whites out the comment. There are moments where these comments are not actually spoilers for the media text in question, but instead, reveals a kind of negativity that fans may not support. Defining some of these comments as “spoilers” immediately whites the comment out of the discussion and also forces those who are interested in these kinds of comments to have to do additional labor to see them. These small moments reflect the ways in which fans are using elements of the formal platform in order to govern themselves as fans, either to censor or to influence the general mood of the discourse that is occurring within these comments sections.

Despite Crunchyroll’s commitment towards creating a space in which fannish affect can flourish within their interface, there are moments when these features backfire. One example where we can see this is through the fan reception of an anime-inspired Crunchyroll Original series, High Guardian Spice, which was marketed as a progressive series that would have abundant LGBTQ representation. Fans used the comment and review affordances of the platform to “review bomb” the series, as well as create a hostile and homphobic/transphobic atmosphere within this progressive series. For fans who did not openly engage with homophobic/transphobic rhetoric, but were still critical of the series, they pointed to the fact that the production was “anime-inspired,” a term that often yields an ambivalent fan reaction due to perceptions of anime-inspired work being of lower quality in comparison to Japanese originated content.

This case study revealed two things: that fans can easily hijack the formal features of their platform to go against the platform itself and that fandom is certainly not guaranteed to use these spaces for progressive or supportive modes of expression. Indeed, one must never forget that a fan’s personal identity always governs their membership into fandom, and in this case, it became very clear that there was an active homophobic and transphobic branch within anime fandom that would foster a hostile environment for LGBTQ global anime fans. Homophobic fans may ban together in order to upvote comments that reflect their own political views, while simultaneously shutting down more productive commentary within these spaces. This is yet another use of the formal features of the platform. While the digitization of fandom does help large corporations to govern fannish affects to a certain extent, fans remain more than capable of using these features for their own governance, irrespective of the platform’s desire. Whether this is progressive and productive for the fandom has yet to be seen.

Given that Crunchyroll is a global platform that serves many different regions, I would be curious to see how this border crossing may affect fan attitudes towards media objects around the world. For example, does the homophobic and transphobic nature of the reviews stemming from the American branch of Crunchyroll affect the way fans may be receiving the work in Latin America or Russia due to certain forms of anime journalism and social media? I would be curious to see if there’s a merging of global fan ethics due to these platform features or a divergence.

Yiyi (respond to Susan):

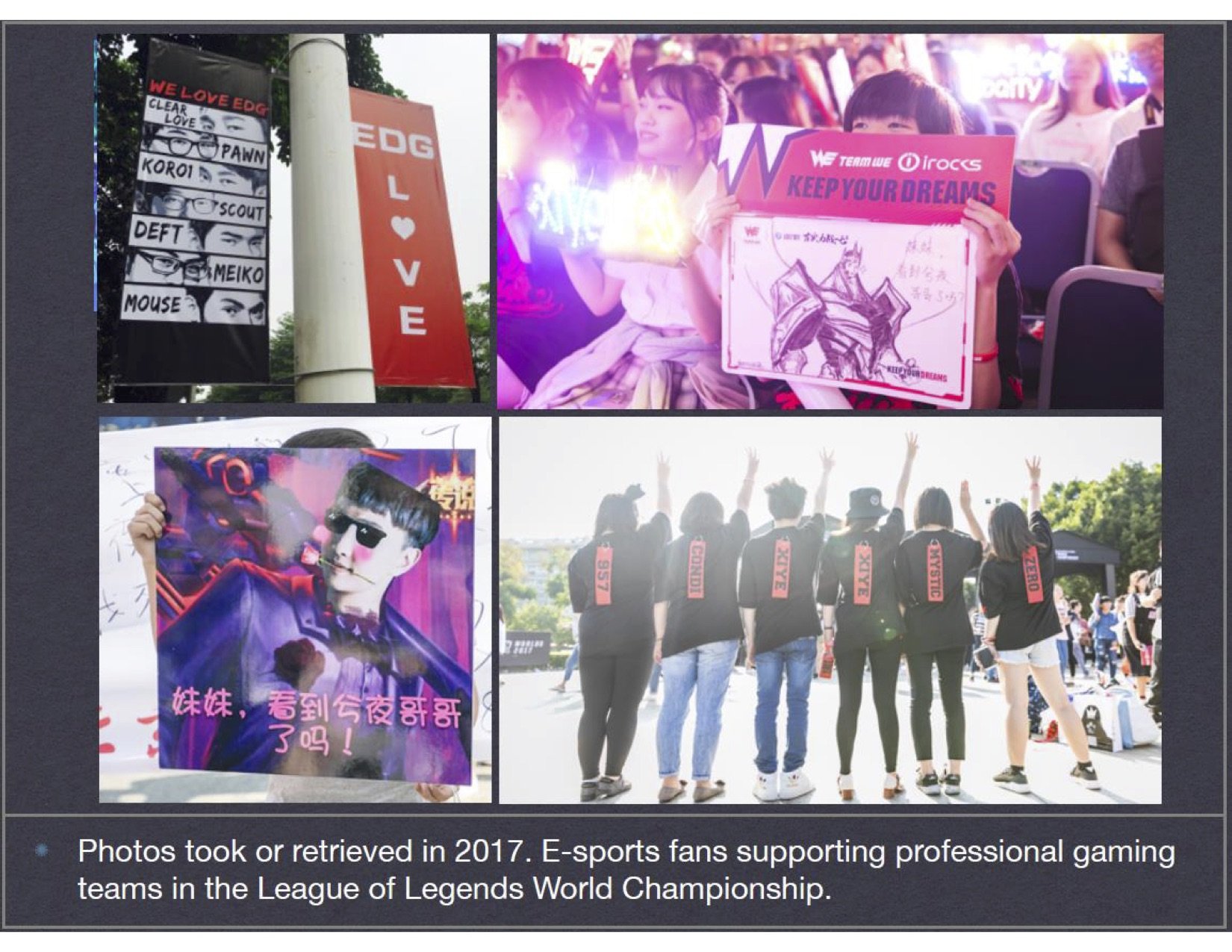

I would like to thank Susan for the inspiring response. Before I come to further discuss the fan-circle and the digitalization of fandom, I’d like to first respond around the impact of historical legacies on fan consumptions. This is a very interesting topic especially when thinking of the linkages between the historical colonial legacies and the current global relations. In China, the consumptions of Japanese anime and K-pop were long considered as “flattering” by the mainstream discussions. Back in 2010, the K-pop fans in China were seriously attacked online because the fans gathered chaotically at the World Expo before a concert inviting the K-pop group Super Junior. More recently, a domestic actor was boycotted because he took a photo in front of the Yasukuni Shrine several years ago. These cases show that the nationalist ideology emerged in China has largely influenced the fan rhetoric and the norms of fan practice in China. The fans, especially whose fan objects involve nations like Japan and Korea, have to paradoxically negotiate with their own historical background as Chinese and the affective passion towards the fan objects. For example, in celebrity fandoms, fans would voluntarily mute online on dates like July 7th (Marco Polo Bridge Incident), September 18th (Mukden Incident), and consider these historically significant dates as the “no-entertainment day”. This kind of norms of practice also becomes something that fans need to negotiate with in the overlapping fandoms, especially in emerging fandoms like the eSports fandom. As the eSports teams in China has started to invite Korean players since 2015, there were a lot of new coming fans from the K-pop fandoms. The conflict between fans of “all-Chinese teams” (i.e. a team with all Chinese players) and fans of Korean players has lasted till today. I agree with Susan that it would be very interesting to see the impact of one’s historical legacies on fan practice especially when the global relations have become intensive again in the recent years, as the contextualized fan participation could become the frontier of nationalism.

Going back to the topic of “fan-circle”, as Susan suggested, I need to further define it as a specifically contextual phenomenon in Chinese fandom. For my research, the definition was summarized from more than 50 interviews I have conducted with fans from various fandoms (e.g. anime fandoms, eSports fandoms, K-pop fandoms, TV fandoms etc.). A “fan-circle” refers to a group of fans with sharing cultural norms, knowledge, and ideologies. At first glance, the fan-circle carries similar meaning with the term “fan community.” Nevertheless, the “fan-circle” should not be interpreted as a particular fan community with its own performances and norms. Instead, it refers to a broad set of norms, rules, culture tastes, and patterns of participation that is cross-community.

According to the interviews, the fan-circle culture has reclaimed the authorial legitimacy of certain affective practices, not on the basis of the moral economy but of a sort of rationale that can only be made sense with specific cultural imagination. Almost all of the interviewees who lived with such struggling attributed it to the influence of “the rules of the fan-circle”. In their narratives, the fan-circle is defined by specific patterns of rules and participation, including the regulation of online practices, supportive activities, sociality, consumption, fan-production, and so on. The formalization of the fan-circle practice is thus seen as a process in which fans explore and legitimate “proper” ways to actualize the abstract and affective fan-object relationship, negotiating it with specific industrial, socio-cultural and media circumstance. With its own characteristics and norms, the “fan-circle” culture has invaded to various fandoms, and thus been questioned, contested and challenged by many fandoms. This is a typical phenomenon that could happen in the trans-fandom when individuals traveled all across the fandoms and communicate with different types of performances and values.

The fan-circle type of fan practice can be easily identified on social media platforms like Weibo, not only because the topics will be mostly about a particular celebrity or fan object, but also because of the formats they have adopted. The formatted content of posts has become a sort of shared knowledge or social capital among the fan community, whereas the term “efficient” clearly hints at the platform logic. In a research proceeded by me and Zhuoxiao Xie (2021), we explored five functionally differentiated purposes of speaking on Weibo: resources, sentiments, fan works, ritualized tasks, and diplomatic interactions. We also found that most of the functional terms used by fans are highly technologically constructed. The construction of proper fan behaviour has shaped the discourse, as the fans selectively utilize certain functions or resources provided by the platform.

This observation echoes to Susan’s case in which fans use the technological settings of platforms like Crunchyrollfor their own governance, but meanwhile also suggests that the governance itself becomes digitalized and technological. For example, the use of “report” on Weibo and the use of “spoilers” both gesture to the logic of digital visibility. That is, fans govern themselves and the fan others by manipulating the visibility of certain (positive or negative) content on the platform. The digital governing has thus facilitated and meanwhile constructed the rule of fan practice. This logic of visibility, as we argued in our research, becomes the logic of fan-circle participation and legitimates the fan-circle as a dominant way of fan participation in the overlapping fandoms. In the case of fan-circle, even when fans start to use the formal technological setting for their own governance, the governance itself is made sense by the platformized rule. This is the reason that I come to argue that the Chinese fan-circle culture is becoming an algorithmic culture in which fans not only use the technology to participate, but also participate in technology. I’m thus very curious whether the logic of visibility or the significance of “traffic data” makes sense in other countries and regions as it does in China. For example, fans on Weibo pay particular attention to the trending, and would devote significant digital labor to control the content appears on the trending list (e.g. posting to heat the hashtag or posting the same content around the hashtag). I would be curious to see how global fandom develops differently in the trends of platformization and digital capitalism.

Bibliography

Yin, Y., & Xie, Z.E* (2021). Playing platformized language games: Social media logic and the mutation of participatory cultures in Chinese online fandom. New Media & Society. First published online. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211059489