Global Fandom: Iveta Jansová (Czechia)

/Firstly, a few introductory words about me. I obtained my Ph.D. in Media and cultural studies at Palacký University in Olomouc. I am currently an assistant professor at the Department of Media Studies and Journalism, Masaryk University in Brno. My main research areas are audience and fan studies. I am part of a research team that studies Czech audiences; we are interested in the changes in media practices brought about by digitalization and globalization. We are also looking at how the Czech media industry (as a small peripheral market in Central Europe) adapts to such changes (e.g., the emergence of on-demand services, etc.) and how audiences navigate their everyday practices in this context. Regarding the study of fans, I am mainly interested in transformative fandoms connected to femslash fans or "lesbian fandoms" in general. So far, I have been reflecting on the foreign context because the representation of LGBTQ+ characters in speculative media is scarce and problematic in the Czech Republic. Finally, my last research area is dedicated to the representation of gender in the crime genre.

Studying fans, it needs to be said, is still a significantly underrepresented topic in Czech academia. This cautiousness reflects a more general "suspiciousness" towards the study of popular culture and cultural studies in general. This ultimately led me to a decision to create a basic introductory course into fan studies during my Ph.D. studies and which I took with me after relocating to Masaryk University. To this day, it is the only course explicitly dealing with fans and fan studies in Czechia.[1] Some progress regarding the study of fans in the region has been recently made thanks to several grant projects[2] focused on contemporary audiences. That allowed closer attention to the changing practices of audiences, including fans. Similarly, different graduate and Ph.D. theses that have emerged over the years[3] play an essential role in broadening the knowledge about (not only Czech) fans and fandoms.

Thanks to one of the previously mentioned grants, our team recently studied both audiences and representatives of Czech entertainment media. This offers me an opportunity to include a brief snippet addressing the potential perception of fans from the perspective of the Czech entertainment media industry. In the interviews with industry representatives,[4] one of our interest areas was convergent practices, niche audiences, and, more implicitly, fans. When asked about these topics, most interviewees believed they are still marginal in the region, so they needn't accommodate such audiences. Even though more substantial changes in the industry have happened in the last five years and are observable mainly in the online sphere,[5] such a stance seems to be shortsighted. It might also result from secrecy during the interviews stemming from a fear of revealing something they considered a company secret and potential advantage over other providers.

Now I would like to pay attention to the more general observations about the fans and fandoms in my country. One of the historically significant fan identity testaments (due to the life behind the Iron Curtain) was undoubtedly (fan)zines created around various interests such as music, sci-fi, comics, or computer games. Because of the communist regime lasting in the area until 1989, this DIY creativity had an underground and sometimes contra cultural essence. This is extensively researched and narrated in Miloš Hroch’s 2017 book, I Shout, 'That's Me!": Stories of the Czech Fanzine From the 80s Till Now. As he pointed out, such practices are not extinct just because we are past 1989: zines are still created by some fans today.

Consistent with the areas of interest, mainly music, sci-fi, and fantasy, often associated with fanzine culture, fans can be quite visible in Czechia. One of the most established popular culture conventions is Festival Fantazie, held annually in the town Chotěboř. It started in 1996 and slowly grew to its current state, hosting around 12 thousand fans of TV series, movies, and games yearly. A brief overview of the programs of Czech-organized conventions (Festival Fantazie, PragoFest, Co.con, ComicCon Prague, etc.)[6] already highlights the common areas of interest that are in significant part happening around international favorites such as Harry Potter, Game of Thrones, Star Wars, Star Trek, Doctor Who, and so on. This means that even if the cons are happening in a specific country and place (e.g., small town Chotěboř with around 9000 residents[7]), they still touch on various sources of fan interest originating from all over the world. The fan practices/interests connected to Czech conventions can thus be more or less locally (e.g., domestic desk/computer games, medieval martial art, comics, etc.) or globally (e.g., cosplay) specific.

The opportunity for multiple belongings (within the context of local/global fandoms) is exemplarily utilized in the Czechoslovakian (Czechs and Slovaks operate together here) fandom of the K-Pop band BTS. Even though fans from both Czech Republic and Slovakia created domestic platforms (e.g., Facebook group) to share relevant content, they mainly operate in English (some in Korean). They are part of the global BTS fandom. When asked in interviews[8], they did not feel like being part of a "Czech fandom," but simply one – international – fandom of BTS. This raises the question of whether it is possible to set a clear boundary around some local and international fandoms. It seems that the lines are becoming quite blurry in many cases.

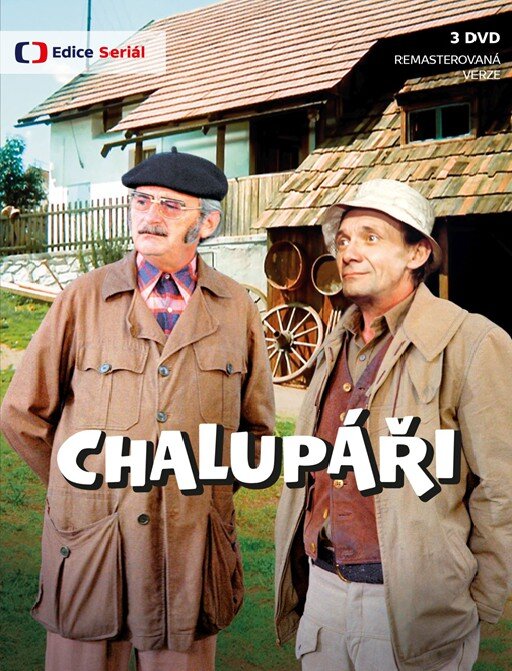

This is true especially in our country, where there is an apparent difference in culture under communism and contemporary culture. Due to the cultural artifacts from socialist production being filled with propaganda, the current audiences (and population in general) seem to be demonstratively apolitical. We can find similar manifestation in the study of popular culture, where a large part of "academic attention" is aimed at the past. One example is research into the popularity of "nostalgia viewing" of the content made before 1989 that is being re-run to this day and still attracts a respectable number of viewers.[9] Another example poses a group of researchers around the Center for the Study of Popular Culture .[10] Even if they are ultimately eclectic in their areas of interest, they still often open themes surrounding fandoms and subcultures from the past (through public lectures or topical conferences).

Contemporary Czech fandoms gather around globally accessible cultural artifacts. At the same time, present domestic content rarely becomes a source of fan activities or cult attention. Even though we see fans reaching out to creators to thank them, ask them questions, or "grill" them about their favorite shows or movies, we are not seeing large followings, rich fan creativity, SOS (or otherwise activist) campaigns, or Twitter exchanges[11] between fans and producers. It is not common to see politically charged activism or enlightening practices connected to popular culture (such as in the case of the Harry Potter Alliance, etc.).

Being a post-socialist country brings about a burden/legacy of the past influencing production decisions and audience relations within the Czech media industries. This poses a challenge for academic research not only in the areas of popular culture and fan studies. Moreover, when the contemporary culture and audiences are so fragmentized and the cleavage between the past and present increases to the point that, with a possible exception of Czech musicians and bands, it is hard to make out a current "Czech fandom" of anything.

Mgr. Iveta Jansová, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Masaryk University | Faculty of Social Studies

Department of Media Studies and Journalism

Brno, Czech Republic

[1] The course also continues at my previous department and is led by my former student.

[2] These projects are part of ongoing mapping of the Czech entertainment media industry and its audiences by (at times more or less closely) cooperating teams of researchers from Masaryk University, Charles University, and Palacký University.

[3] The existing works that I was able to encounter are covering a wide range of topics such as music fandoms (e.g., a local K-Pop fandom, a comparison of different national music fandoms, etc.), transmedia narratives and world-building in TV series, quantitative mapping of Czech Harry Potter fandom, slash fiction in Czech Harry Potter fandom, real person slash in figure-skating, femslash in American TV series, queerbaiting and so on.

[4] Our interviews were carried at the turn of the years 2019/2020 and were conducted with producers, analytics, marketing managers, etc., from all the significant content suppliers in Czechia.

[5] Czech Republic is sort of a latecomer in this regard. For example, Netflix became accessible in 2016 (and went through significant localization only in 2019), HBO GO was accessible to the broader public in 2017.

[6] I am not including those dedicated to a specific title such as WHOCON etc.

[7] A little side note is appropriate here: localized activities can have a substantial financial impact on the region. Taking the example of Chotěboř and other smaller towns - hosting annual cons can mean significant economic benefits for the cities.

[8] A study conducted by one of my graduate students.

[9] Irena Reifová from Charles University has detailly researched this topic.

[10] This Center is not a place or a building, it is a civic association. It was established in 2009 by several postgraduate students from different departments of the Faculty of Arts by Charles University in Prague. The researchers around the Center try to popularize knowledge about popular culture and related topics. Their activities are described in detail on their website http://en.cspk.eu/.

[11] Twitter has only around 400 thousand users in the Czech Republic. In comparison, Facebook has over 5 million and Instagram 2 million.…