Global Fandom: Rukmini Pande (India)

/Bus advertisement for KPop group Red Velvet's Japan mini album

Credit: Photo by Hiu Yan Chelsia Choi on Unsplash

I begin with an acknowledgement that I, as well as many scholars present (and absent) in this blog conversation series, continue to grapple with the deep inequities exposed and exacerbated by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The decisions of many conferences in the Global North to move back to “normal” formats with an emphasis on in-person attendance with its attendant networking and professional opportunities are far from value neutral. They signal a willingness (perhaps even an eagerness) to not just return to previous levels of academic inequity and inaccessibility, but further retrench them[1].

In this context, I welcome this conversation series being hosted by Henry Jenkins, as it goes some way in addressing those inequities. However, a single endeavour can only do so much. I hope that my colleagues located in other influential Global North institutions and organizations respond to the urgency of the present moment and establish similar forums and avenues of scholarly engagement, support, and publication. No discipline can claim global relevance and reach without working to dismantle mechanisms that alienate so many colleagues and institutions from participation and leadership roles.

I use these observations to foreground their inextricability with all our current academic lives because they connect directly to many of the key questions faced by fan and audience scholars in a global context marked by precarity and inequity. I pose three as rhetorical jumping off points in the hope that they will connect with other pieces in this series to form a set of provocations for the field.

1. What does it mean to engage in fan studies at a time where our mediascape feels more networked, more globalized, and more fractured than ever before, both in terms of texts and the platforms that host and transmit them, as well fans themselves?

2. To what extent are our current methods and theoretical models equipped to engage with the evolving and fractured dynamics of fan communities as related to broader cultural, political, and economic issues wherein individuals often hold extremely divergent views?

3. And finally, how do we acknowledge and tackle the fact that all fan communities today are interfacing explicitly with deeply entrenched, globalized and networked social formations amplifying fascist politics (white supremacy, racism, gender-essentialism, xenophobia, religious fundamentalism, enthnonationalism, and neocolonialism amongst many others) without setting up binaries between “progressive” and “reactionary” fandoms?

The animating focus of my research so far has been to make visible the role of race and racial identity in anglophone online media fandom as well as within the discipline of fan studies itself. I published Squee From The Margins[2] in 2018, and an edited collection, Fandom Now In Color[3] in 2020, as part of this broader project. I have also discussed the effects of institutional whiteness on fan studies methodologies and publication processes[4].

One of my primary arguments remains that issues of race/ism, particularly around Black characters, interrupt broadly held assumptions about media fandom spaces as uniformly politically progressive, offering a special refuge to fans from marginalized identities. These arguments remain relevant as we see an increasing polarization in fandom spaces around issues of racist fanwork, micro and macro-aggressions against vocal fans of color (especially Black fans) who identify problems in fandom spaces, and a concerted push to undermine any critiques of the same which seek to identify the workings of systemic racism, rather than individual issues by “bad” actors. This has also been pointed out by acafans such as Stitch in their detailed rundown here[5].

My work has also held up the hope for solidarity and coalition building around the category of “fan of color” in fandom spaces, pointing to a longer legacy of similar work lead by critical fans around events such as RaceFail ’09[6]. I continue to believe in the power and vital importance of such coalition building but want to reiterate that identifying and dismantling structural white supremacy is extremely difficult work and requires sustained effort. It does not begin or end with the personal identity of individuals. The power of whiteness operates in many ways including the co-option of marginalized voices and identities. Further, it is vital to understand the increasing role of majoritarian political ideologies (often rooted in ethno-nationalism) in the global mediascape. Fan communities, themselves more transnational and transcultural than ever before, have always been and continue to be profoundly influenced by these dynamics.

Fandom spaces and communities have been demonstrably proven to be powerful arenas for civic participation ranging from pushing for changes in specific media properties, to broader socio-political mobilization. While initially optimistic about the progressive potential of such activity, recent scholarship has also taken into account the reactionary elements in these spaces. This is an extremely important step.

Mel Stanfill lists a set of “jarring questions” in the introduction of a special issue on “Reactionary Fandom” which is a good summation of the concerns of this influential branch of scholarship. They ask, “What can we understand about reactionary politics by examining them through the lens of fandom? Should Gamergate be understood as the beginning of the alt-right? Do models of gift economies in fan fiction help us understand the production and circulation of conspiracy theories on YouTube? Can sexism be understood as fanon? Is white supremacy a fandom?”(Stanfill 2020, 2).

These are all extremely interesting provocations and the special issue’s scope includes a case study of fanfiction-based fandom by Anastasia Salter (2020). This also connects to Poe Johnson’s earlier perceptive questioning of fanworks’ troubled relationship with the Black body (Johnson 2019). However, taken together with other work on the same area, there continues to be noticeable skew towards either using the tools of fandom studies to examine explicitly white supremacist organizations like the MAGA movement or QAnon in the USA, or interrogating fandoms with observably reactionary elements in the majority such as Gamergate or sports fandoms (Miller 2020; Lobinger et al. 2020; Johnson 2020; Reinhard, Stanley, and Howell 2021). I am not trying to minimize the importance of this work but rather underline that it’s equally vital for scholars to understand more covert forms of white supremacy and other forms of majoritarianism operating in fandom spaces assumed to be resistant to such ideas.

I would argue that while the question of white supremacy as a fandom is perhaps debatable, the presence of white supremacist structures in progressive media fandom is now well evidenced. Indeed, I would go further to state that the backlash against anti-racist efforts in these spaces, by branding them as censorship and policing of fannish pleasure, is actually gaining ground because it is couched in the language of social justice. These are admittedly complex issues but the need for scholars to be aware of these dynamics has never been more urgent.

To expand on an example, many fandom scholars and commentators saw the mobilization of K-Pop fandoms around the 2020 BLM protests in the USA as a potentially politically transformative act. However, a more detailed analysis has shown those fandoms to be as marked by anti-Blackness as any others, as detailed here by Miranda Larsen[7]. To put it in another way, we cannot come to broad conclusions about the politics of any space, even one with a majority of individuals from marginalized identities, without sustained engagement and granular analysis.

This also extends to fandom spaces engaged in the consumption and creation of queer content, which has often functioned as a kind of shorthand for scholars, almost automatically designating those participants as having a larger progressive politics. However, in a world where queerwashing and homonationalism are extremely powerful forces, shaping everything from foreign policy, to media texts, to fan reactions, we need more robust and critical theoretical approach.

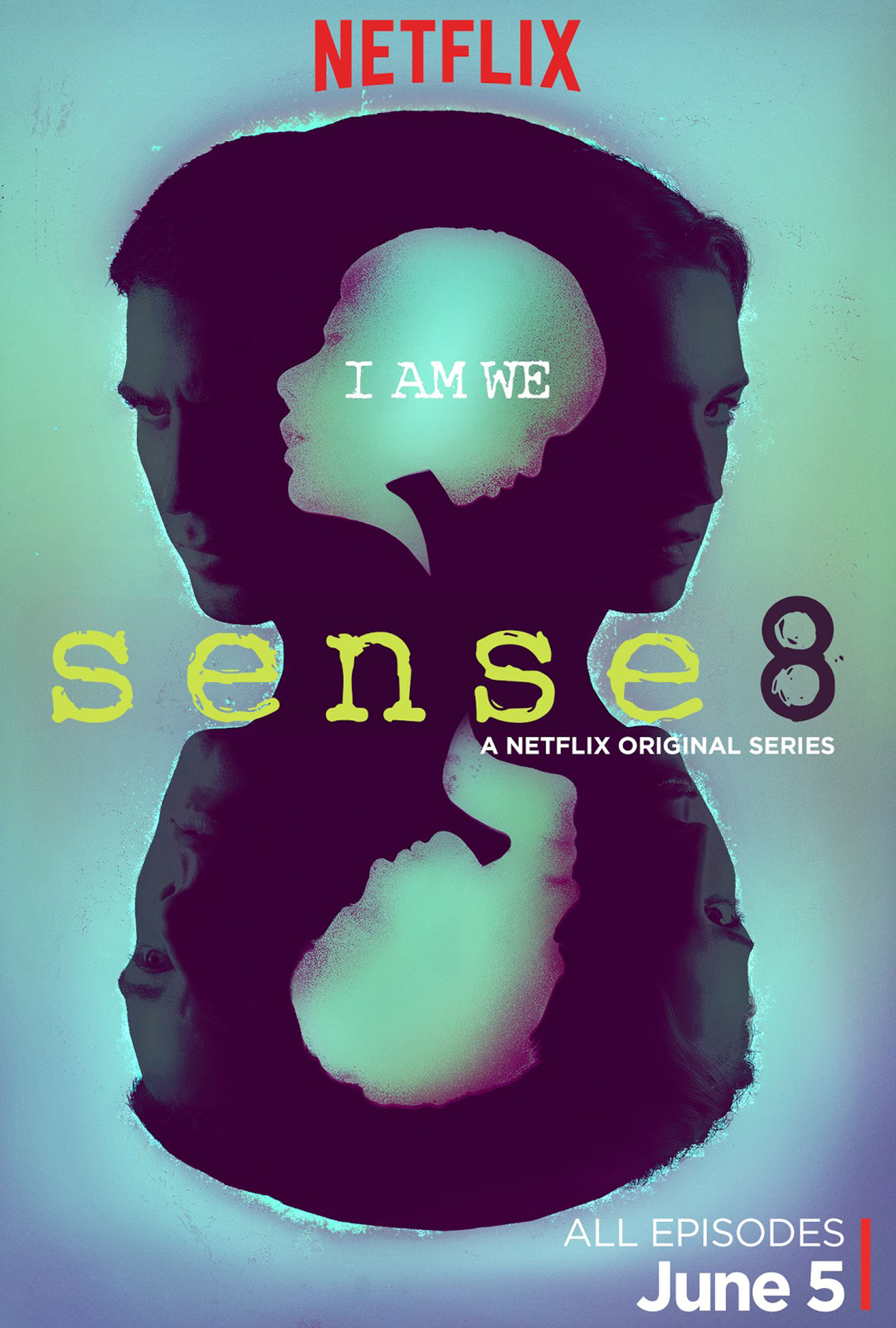

To give an example relevant to my current geo-political location, the fandom of USA television series Sense 8 (2015-18) (created and directed by the Wachowski siblings) had all the markers of a queer and racially diverse space which might have been expected to result in a politically progressive community. However, the series itself had some extremely disturbing narrative threads, including one centered on India which reinforced dominant Hindu nationalist beliefs. These same beliefs, now very much the mainstream, have pushed the country further and further into authoritarianism. Today, any effort to critique Hindu nationalism locally or internationally is framed (erroneously) as colonialist and racist. The storyline in the show itself did not generate much debate or protest within the fandom, precisely because it was framed within a queer utopic universalist frame which made locale-specific critique difficult to explain or sustain. Similar dynamics are also visible in many contemporary fandoms which paper over the problems of media texts with ethnonationalist or other majoritarian themes with un-nuanced appeals to “diversity” and “representation.”

The point I wish to make through these examples is that while media fandom spaces continue function as spaces of connection and enjoyment for fans from marginalized backgrounds, scholars must push beyond single lens understandings of political and social affiliations. Fan studies must move beyond a shallow perception of intersectionality merely as a politics of citation or representation into the conditions it enables and the contexts it functions within; we cannot resist authoritarianism through the mere performative co-option of what sounds like resistance instead of the realities of what we are enabling in the world.

Rukmini Pande is an Associate Professor in Literary Studies at O.P Jindal Global University,

India. She is currently part of the editorial board of the Journal of Fandom Studies and Mallorn:

The Journal of Tolkien Studies and has been published in multiple edited collections including

the Wiley Companion to Media Fandom and Fan Studies and The Routledge Handbook of

Popular Culture Tourism. She has also been published in peer reviewed journals such as

Transformative Works and Cultures and The Journal for Feminist Studies. Her monograph,

Squee From The Margins: Race in Fandom, was published in 2018 by the University of Iowa

Press. Her edited collection, Fandom, Now In Color: A Collection of Voices, bringing together

cutting-edge scholarship on race/ism in fandom, was published in December 2020.

References:

Johnson, Poe. 2019. “Transformative Racism: The Black Body in Fan Works.” Transformative Works and Cultures 29 (March). https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2019.1669.

———. 2020. “Playing with Lynching: Fandom Violence and the Black Athletic Body.” Television & New Media 21 (2): 169–83.

Lobinger, Katharina, Benjamin Krämer, Rebecca Venema, and Eleonora Benecchi. 2020. “Pepe–Just a Funny Frog? A Visual Meme Caught Between Innocent Humor, Far-Right Ideology, and Fandom.” Perspectives on Populism and the Media: Avenues for Research 7: 333.

Miller, Lucy. 2020. “‘Wolfenstein II’and MAGA as Fandom.” Transformative Works and Cultures 32.

Pande, Rukmini. 2020. “How (Not) to Talk about Race: A Critique of Methodological Practices in Fan Studies.” Transformative Works and Cultures 33 (June). https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2020.1737.

Reinhard, CarrieLynn D., David Stanley, and Linda Howell. 2021. “Fans of Q: The Stakes of QAnon’s Functioning as Political Fandom.” American Behavioral Scientist, September, 00027642211042294. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642211042294.

Salter, Anastasia. 2020. “#RelationshipGoals? Suicide Squad and Fandom’s Love of ‘Problematic’ Men.” Television & New Media 21 (2): 135–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419879916.

Stanfill, M. 2020. “Special Issue: Reactionary Fandom.” Television & New Media 21 (2): 123–217.

[1] I am referring specifically to the relationship of “global” media and audience studies scholarship whose power centers of publication and privilege continue to be located in the academic structures of the Global North. I do not mean to dismiss the many nuanced locale-specific conversations (such as in India) around higher education where access to the internet and associated digital technologies are a contested terrain.

[2] https://www.uipress.uiowa.edu/books/9781609386184/squee-from-the-margins

[3] https://www.uipress.uiowa.edu/books/9781609387280/fandom-now-in-color

[4] https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/1737

[5] https://stitchmediamix.com/2021/09/08/where-are-we-now-ao3-anti-racism/

[6] While “fan of color” is used quite broadly in fandom spaces it can also be linked to the history of the term “women of color.” The latter was initially conceptualized as a category of active organization and coalition building rather than of fixed and static identity by Black feminist activists at the National Conference for Women in 1977 in Washington DC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=82vl34mi4Iw

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TLUWN1l2ZMU