Global Fandom: Yiyi Yin (China)

/I’m Yiyi Yin. I self-identify as an aca-fan and have been working on Chinese fandom studies for several years. In 2002, I wrote and posted my first fanfiction on a BBS where fans of the Japanese animation B’TX congregated. I was 12 years old back then, and hardly knew anything about fandom or fan culture. I even had never heard the word “fans.” Every day I discussed the storyline of B’TX with one of my neighbors who was also fond of it, and wrote poems together for our favorite characters. I remembered how we snuck into her mother’s office and dialed-up to the Internet, reading everything we could find on a themed forum related. I remembered my very first post on the forum, which was a repost of another B’TX fanfiction from one forum section to another. As I recalled, my personal experience as a “fan” probably started from there, even though I had no idea of such identity at that time.

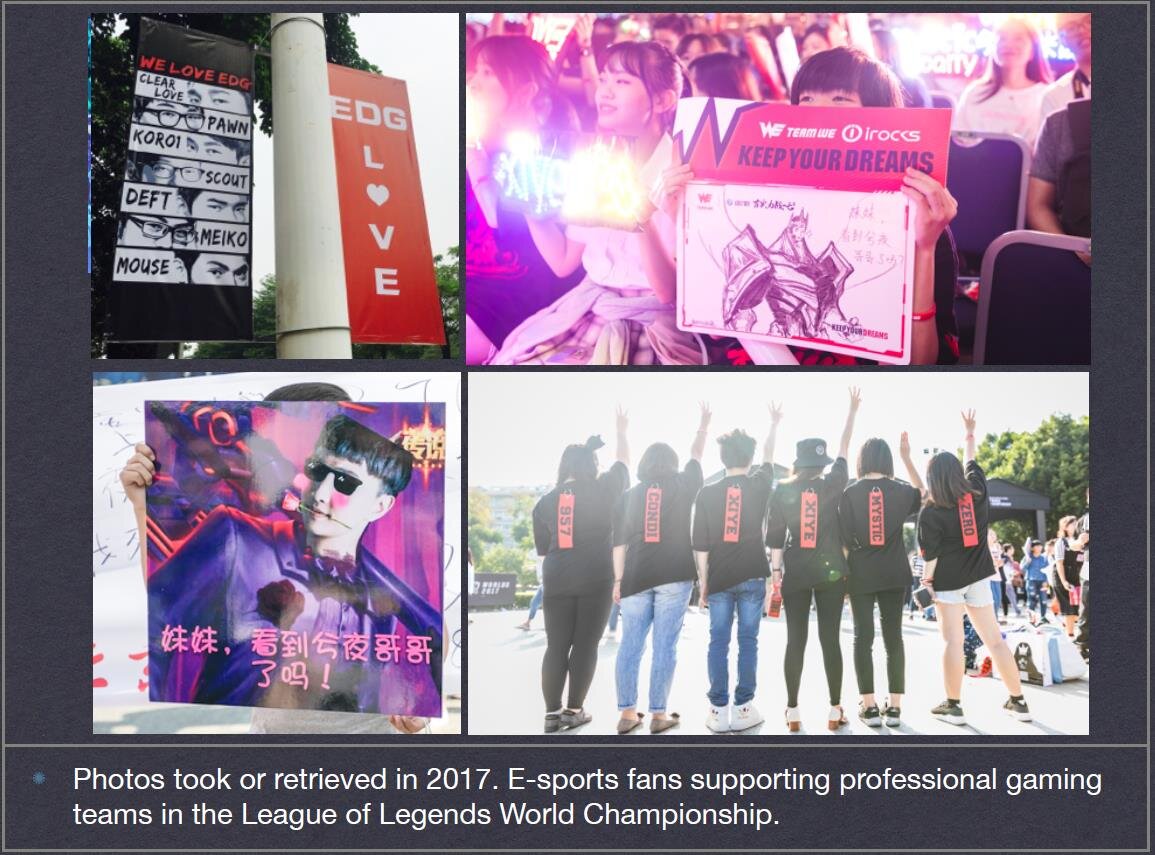

Since then I’ve been a long-term observer and participant of multiple fandoms, including some in Japanese manga, some in English television dramas and films (e.g. Lord Of The Rings, Sherlock, and Marvel movies), some in popular music, and some in eSports. Growing up in the 1990s in mainland China, my own experience as a media fan was accompanied by the process of becoming a “netizen”. In terms of the expanding media industry of China, the period between the 1990s and the 2000s was also a critical process in which the marketization, commercialization, and the national “soft power” construction significantly progressed. Meanwhile, as the acceleration of the process of globalization has led to a drastic transformation of fan culture in China, the fandom has emerged from hitherto underground development and community-based activity to a vibrant social group operating on the Internet. During this time, I, as a teenager, inevitably encountered new genres of media and cultural products, new patterns of participation, and new forms of fandom. For me, the meaning of the term “fandom” has been constructed precisely during this time, as a naturally dynamic and relational concept that never restricted to only one single object.

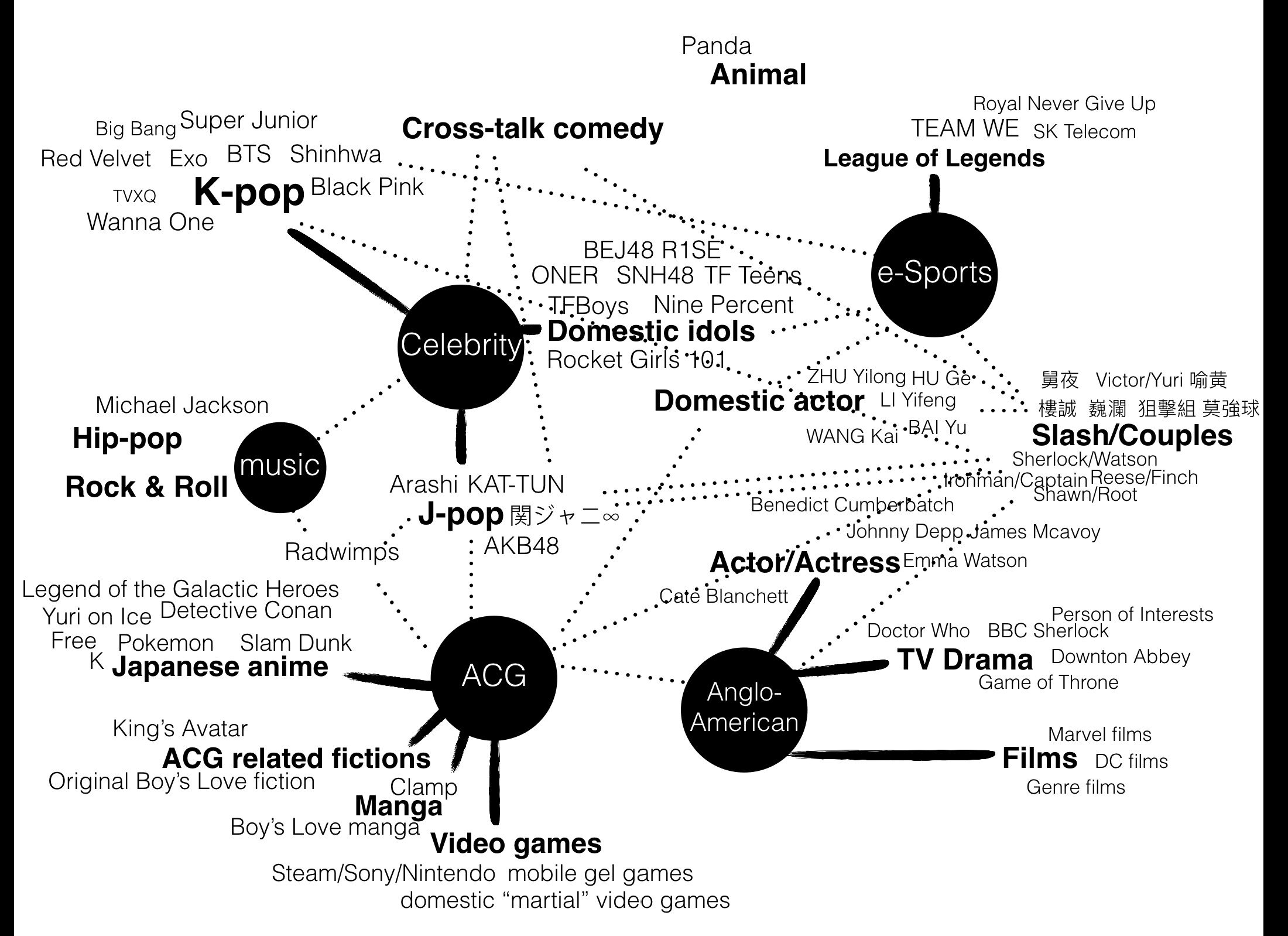

In mainland China, the development of local fandoms was not linear, as it was varied constantly by waves of foreign culture. The local fan culture was firstly introduced into mainland by Hong Kong celebrities and their fans, and thus formed the earliest celebrity fandom in mainland China. Another influential fan culture was shaped by the imported Japanese animations in the late 1980s. The ACG culture and Otaku culture influenced Chinese fan culture to a large extent, which have made the Chinese fan culture notably different from the Western country where Star Trek was always noted as the early fan-text. It is fair to say that the transcultural Otaku culture initially shaped the Chinese fan culture in terms of the patterns of participation, ways of expression, and communal appearance. However, the Japanese cultural products were mostly banned in China in the early 2000s. The materials for fan consumption have thus changed, way before the Chinese fan culture has been formalized by the Otaku culture. Since then, along with the development of the Internet, the Chinese fan culture was primarily influenced by the K-pop celebrity culture, and then the Anglo-American traditions of media fans. When the so-called domestic fandom focusing on local celebrities and cultural products emerged in around 2005, the Chinese fan culture has become a very hybridized and multi-cultural combination of various subcultural traditions. Figure 1 shows the fandoms that my interviewees involved. Almost everyone has involved at least two fandoms in the past decade. The fandoms are thus interconnected with a flow of participants.

Figure 1: Hybridized online fandoms in China

Interestingly, these foreign waves, including Japanese Otaku culture, Hong Kong/Taiwan celebrity culture, Hallyu, Western media fan culture, had not appeared as separate fandoms in China. In the age of digitalization, we’ve seen different patterns of fan cultures clashed, negotiated and converged especially in the 2000s. My research interest thus comes from the dynamic development of fan culture in China, especially how fan performances are constantly negotiated and reconstructed, while fan norms, values and cultural practices are formalized and legitimated. My recent works focused mostly on the phenomenon of “fan-circle” in China, which was defined as a dominant pattern of fan participation, involving intense digital labor and regulation of online communicative practices, sociality, media use, consumption and production. [YY1] The fan-circle became discursively powerful in the past decade, ruling out other fan performances by establishing new moral values and redefining the legitimacy of being a fan. These fan-circle moral values first penetrated the popular or mainstream fan communities such as ACG[HJ2] (Animation-Comics-Games) and celebrity fandoms, and then the relatively marginalized or underground communities like eSports and crosstalk fandoms. In this process, fandoms have become interrelated, without clear-cut boundaries separating each fan realm. Instead, the new boundaries have been set as fan-circles, where fans instantly step in and out to struggle with their own cultural identities of being fan.

My general interest is to see the process of formalization of the fan-circle [HJ3] [YY4] and its rules in multiple fandoms (Yin, 2020a). I and Dr. Xie Zhuoxiao from Nanjing University first noticed the technology-specificity of fan-circle, as it largely reflects the platform setting and algorithm in terms of how fans speak, consume, produce and use the media (Yin & Xie, 2018). One of my works (Yin, 2020b) examined particularly the Chinese online fandom as an emerging algorithmic culture in which the ongoing interaction among affect, fan subjectivity, and the algorithm continually shapes and reshapes the everyday fan practice in terms of its sequence of acts, norms, and ways of thinking. In this dynamic process, some activities have been formalized into everyday practice, with authority borrowed from the commercial or industry framework, while others are still negotiated by fans in playing with the rules of the algorithm. The platforms and institutions such as Sina Weibo strategically embed the logic of data in daily fan practice by promoting numerous algorithmic operations including all the indexes, ranking and their rewards. The digitalization significantly shapes the fan performance when it promises certain affective fan-object relationship. The rematerialization of data has allowed the fans to connect themselves to the fan objects that were inaccessible in the past. Through practicing around the data, fans can actualize certain relationship to the foreign celebrities that were out of reach before.

Figure 2: The popularity ranking designed by Weibo

It is also very interesting to see how fans, including the fan-circle participants, make use of the technological resources provided by the platform in unexpected ways. Examples might include how fans appropriate the “report” function to achieve their own goals, and how they flood to resist against the visibility algorithm manipulated by the platform. I’ve seen a case in which the Weibo trending topic was originally about one thing (e.g. “Marvel screening”), but was transformed by fans into a completely different thing by flooding with Weibo posts containing the same keywords yet in different combination (e.g. “Marvelous film screening”). For those who clicked the trending topic without knowing the original event, the content of the trending topic has been efficiently changed by fans. In doing so, they still claim to control the visibility that is powerfully manipulated by the platform and the media producers engaged. In cases like this, fan agency is still potentially creative in a sense that fans would never entirely compromise to the dependency of commercialized cultural industry.

I discussed mostly about how fan-circle is technologically specific. And I am now interested in how and why this algorithmic fan culture can be culturally specific. For instance, Weibo was known as similar to Twitter in terms of its technological settings and social media functions. In media use, fans on both Twitter and Weibo participate in producing Trending, Hashtags, Super Hashtags. Yet the specific patterns, rules, and purposes of fan participation vary. A forthcoming paper of mine and my coauthor would examine the very particular communicative practices of celebrity fans on Weibo, but we have not yet elaborated it from a comparative perspective.

Another interesting but rather pessimistic concern about the cultural specificity of fan-circle is the politicization of fan culture, which can also be seen in other countries (e.g. the fans of Donald Trump) but is especially noteworthy in China due to its complex socialist tradition and political scene. The stressful cultural censorship has forced the fans to further regulate their own participations to prevent the possibility of being criticized or even banned. While there has been a dangerous trend that fans make use of the authorial power to attack the vital fan groups or fan individuals. In fact, the use of “report” function can be seen as a case in which fans take use of the “punishment mechanism” to shut down the posts they don’t like. In recent years, along with the increasingly strict control of Boy’s Love literatures, some fans even report the disliked fanfic to the governmental Weibo accounts. When fandom is becoming more and more mainstream, it is noticed not only by the capitals but also the political actors as potential social power. As the political intervention and fan activities have progressively overlapped, the politicization of fan practice is becoming an increasingly significant and another complicated aspect of the fan-circle phenomenon.

My Projects for References

Yin, Y. (2020). An emergent algorithmic culture: The data-ization of online fandom in China. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(4), 475–492.

Yin, Y., & Xie, Z. (2018). The bounded embodiment of fandom in China: Recovering shifting media experiences and fan participation through an oral history of Animation-Comics-Games lovers. International Journal of Communication, 12 (18): 3317–3334.

尹一伊(2020),《粉丝研究流变:主体性、理论问题与研究路径》,《全球传媒学刊》,7 (1):53-67页。