How Do You Like It So Far?: Sarena Ulibarri and Ed Finn on Solarpunk (Part Two)

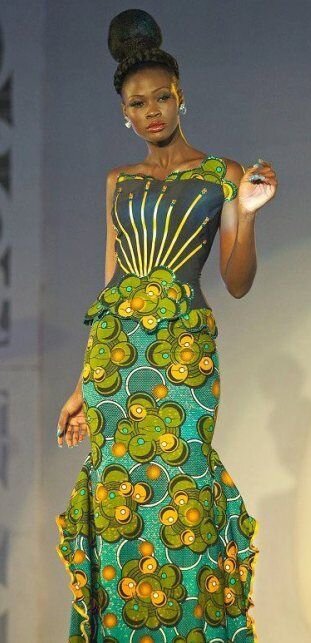

/HJ: A lot of the worldbuilding is going on not simply in the stories, but in the art and people are designing solarpunk worlds whichever radically different aesthetic from much science fiction art previously, they definitely don't look like the Apple store that Serena was talking about.

SU: Yeah, I think the aesthetic is really important to the movement. I think it's what gets people's attention, more than the messaging necessarily, at least in the beginning. And yeah, it's kind of, it's a nature-based, it's kind of maximalist. And it's inspired by Art Nouveau, oftentimes - not all solarpunk is but I think Art Nouveau is a really important aspect of the aesthetic. Not only because it's a beautiful way to work in like nature imagery, but also historically, the Art Nouveau movement was a reaction against industrialization and capitalism. So it kind of fits in that way too. Art Nouveau rejects the idea that beauty is something that's just reserved for the rich. This was an artistic movement that everybody is entitled to a beautiful world. And that beauty and practicality are not mutually exclusive. So that's very much in line with solarpunk ideals. I'd love to see more solarpunk works really fully embrace the Art Nouveau aspect.

EF: Yeah and art is this technology for feeling, right? It's helping you. And I think imagination, one of its fundamental jobs is empathy, and allowing us to imagine the lives of other people and to feel things that we haven't felt before. And I think that some of the most interesting solarpunk art that we've been involved with at CSI has done that.

We did this project a few years ago called Luna City, which was like an immersive, theatrical experience of living in a city and on the moon in 2175, you got to go on a tour of this neighborhood. And it had lots of bamboo and a river running through the middle of it, and all these green plants totally unlike, you know, the Star Trek future or the 2001 future, and really organic and everybody was wearing these like flowing, you know, robes that that don't feel like space futures at all. And that I think was really powerful as a way to - it was a solarpunk future on the moon, right? It was a way to experience this integration of technology and the natural and the human in a way where, where people could actually live there. You can actually say, like, "Oh, I can actually live here." Whereas if you pause, you will get a lot of this sort of classic science fiction, these really Stark, modernist lines and you're like, "Would I want to live there?" You know, like, where do you put your trash? You know, does nobody own anything? Or always the most challenging question, "How could you raise a child?"

CM: Everything is sharp, it's all pointy!

HJ: Well, you're touching on the design aspect and the fashion aspect of, again, if you look up solarpunk online and add fashion, you will see these remarkable designs taking place there as well, which is how it starts to bleed over into a lifestyle or a way of living in the world that solarpunk might represent. So can either you say a little more about fashion or music or some of these other embodied aspects of solarpunk?

SU: I keep waiting to see like really good solarpunk cosplay. And maybe when we come back to being able to do you know, cons again, after the pandemic, maybe we will be able to see more of that. But I, it's I've seen it mostly conceptual, rather than really embodied. But I might just be running in the wrong circles to really be seeing it. I think there's ton of ton of potential. And there's some really interesting, like sustainable fabrics, you know, mushroom leather, for example. And, you know, things like that, using different types of sources to create fashion. That I yeah, that I think have a lot of potential and are right now just very niche and probably too expensive to really be considered like solarpunk. But I mean, what if you can not only grow your own food, but what if you can grow your own clothes, like that would be amazing. That would be a really interesting change to fashion.

EF: I think the other place you see it is in, you know, weird and amazing research projects. So I had a student who's graduated from ASU, he's at MIT now, who was really interested in different fashion futures, solar futures, solarpunk futures, he was working on growable robots at our, when he was with us. So the idea that you would have something that would sort of grow on its way to Mars, and then it could be a robot once it got there. But he also did some really cool stuff with fashion. And I think that fashion is always pushing the boundaries of material science in lots of ways, right? They turned to the underwear manufacturers, when they were designing the first spacesuits for the Apollo program, because those are the people who really knew how to, you know, create support and structure. And the fashion now I think in solarpunk is looking for these, like, you know, programmable fabrics, and all this stuff that you can, is like right on the cusp, and you can do in a prototype that might or might not light on fire, but you know, isn't... I'm really excited, I agree with you Sarena, that, I think in the next few years, we're going to start to see a lot more wild and interesting stuff. Because people, that's another way in which you also make the future really personal, you know, if you make the future, something that you can put on and wear. I think there's a great interest in that. And fashion is this space where it there's a lot of ecological consequences to fast fashion, you know, disposable clothing. And it's one of those areas where I think there's a big imaginative shift that is maybe coming in the next few years.

CM: Yeah, I mean, I think it's, as you say, it's both palpable, when you can wear it, it feels real. But it also makes it feel possible, right to me, and so it feels in that way, it's like embodying the kind of solarpunk future that we're talking about in a way that says it's not only in the future, it starts now. And then the last piece, which is really important is ideally, it's cool, right? Like because this is you know, we know this from the Black Panthers and elsewhere like you want the revolution to look cool, so you want to be part of it. Right? It doesn't want to be that bad Star Trek or whatever that other futuristic version, in which there is no fashion there is no style. It's we're wearing uniforms.

EF: Lycra, it's lycra.

CM: Exactly! No, I want the flowy gowns from the moon or whatever the thing is right, that were grown in your backyard and yet look fabulous and don't stain!

SU: Yeah, and well it helps personalize it as well. Right? Not the monochrome jumpsuit, but the, you know, the really personalized, handmade, artistic piece of fashion.

CM: I mean, that feels to me like it's a reminder of the provocation that, it's back to what you said earlier, that it is personalized, that is localized, that the future doesn't need to be mass produced, but that we can imagine a different way of having sustainable futures which are indeed tied to precisely not that mass approach to things, so that to me feels like a profitable literally and figuratively, a really interesting space to dig into as something that maybe another earlier you know, edge of where solarpunk meets our current world. I'm sure there are other spaces like that, that feel kind of ripe for, that you can see, kind of emergent?

SU: Well, have you seen the Chobani commercial?

CM: No.

SU: Okay, look up the most recent Chobani commercial, it is absolutely solarpunk. And it's designed in this very like, yeah, actually one of the artists was a winner of a solarpunk art contest. So, I mean, it doesn't just look that way. It is like intentionally drawing from solarpunk aesthetic. It's a very short little story about like, you know, the future of sustainable farming. And so I was really kind of skeptical of it at first, because big corporation using solarpunk aesthetic, like, I don't know how I feel about that. But I looked into Chobani as a company, I think that they're doing about the best they can do in terms of sustainable sourcing and recycling and things like that, and they have goals, they have, like measurable goals that they're working towards. And so, you know, it's not the same as if, say Coca Cola was doing this. You know, there's been a lot of greenwashing and stuff.

CM: There goes our Coca Cola sponsorship.

SU: Oh sorry, you can cut that out!

HJ: Nope, in our dreams...

CM: That's a great indication, right? When the private sector, when they pick up on a thing, they're like, "There's some value here," right? "This is a story we want to tell." And I hear the ambivalence, too.

SU: But you know, I thought about it for a while. And I debated, am I behind this or not? And I think I'm happy that the solarpunk aesthetic is reaching more people, even if it is through a yogurt commercial.

EF: I think there are a few areas where our technical reach is still way ahead of our, certainly our moral grasp, but also sometimes just our imagination grasp. And I think synthetic biology is one of those areas where we have no idea what we can do right now, we can do so many things. And the tools are terrifying and incredible. And we have some great science fiction about synthetic biology and you know, different futures we could work towards. But I feel like we haven't even scratched the surface. And this idea of you know, growing stuff, like growing tools, growing building materials, growing infrastructure, right is really interesting and exciting the intersection of biology and material science, because there's so much of our built environment that feels, it's so industrialized, that it's almost magical, you know, we have no idea where it comes from, how it's made, what it costs to do it. And we're going to need to learn a lot more about those things and sort of demystify some of these industrial processes and open up some of these black boxes, and then maybe create new kinds of magic, where it's like, "Oh, it's local," like the farmers market is magical, you know, you go to the farmers market and eat this, buy this food that was grown here, wherever you are. And there's something amazing about that, and it tastes really good. Now, so that kind of localization and starting to create a new, new imagination, feedback loops, if that makes sense, around different - and where you actually know who all the people are, right? And you know, where your stuff comes from. Is at once incredibly mundane and boring. And we're talking about like, you know, your plates, or I don't know, building a new building or something. But it also I think, could be really amazing. They're doing all this crazy stuff with, I think, as Sarena mentioned, mushrooms and fungi before, right. I don't even know what is going to happen. But I think that's going to be a major set of transformations as people - all of those people who aren't probably talking to one another right now, start to talk together more and say like, "Oh, we've got this thing. We could do it for this."

SU: Yeah, I think that's a big part of what's going on right now is just everyone's in their own little corners. And it's not, it's not the collaboration that it could be. Another thing that I was reminded of when you were talking, I'm not even sure what remind me of this, but I saw an article about, there's like a robotic squid or something like that, that's helping to clean up the coral reefs. And so it looks like a squid or a fish or something and so it can kind of sneak in without disturbing the natural sea life, but its job is to go in there and remove waste and repair damages to the reefs and things like that. So, you know, there's all kinds of little, not little, that's probably a major project, but all kinds of projects like that that are that are happening. They're just not, large scale, they're not being utilized quite as much as they could be yet.

CM: To come back to kind of solar from that, from those sorts of developments to solarpunk, it seems like one of the neat things is to be able to kind of place those in conversation with each other, right? As not isolated developments around how we're using fungi or, you know, kind of the intersection of biology and mechanical things, but rather to see them as on this journey towards the future that we want, or more of the future that we want, that embodies some certain set of values, even not really precisely defined ones, but sort of a general direction. And that to me, that's what you could call, I don't know if solarpunk is a philosophy, but as an orientation for the people who are creating or using those tools or practices or technologies, that to me feels really valuable, right, to say, not just that we're, yes, you're cleaning up the reef, but it's within this broader context of this direction that we're going, and that that would seem to offer opportunities to put those different practices to collide them with each other and to see what comes.

SU: Yeah, I absolutely agree with you. I have nothing to add to it. That's, yeah.

EF: Picking up on something Sarena said before, you have to give people permission. And a lot of people don't feel like they have permission to do this right now. And also, the stories are not, at least the stories we make at CSI, are not intended to be the final answer. They're really just prompts to get people to do to do their own storytelling, right? And I think that what you really want is to inspire this sense of agency and responsibility. So people start to say, "Well, what about our reef?" Right? What if we started, what if we became custodians of this and started to feel a sense of responsibility and agency around it to start to care for it? Then we're gonna figure out a way, like, we're going to start with that goal, and then we'll figure out how we pay for it, and what the, you know, how we do it, and how we account for everybody's time and make it sort of make sense in the rest of the world. But changing that fundamental orientation, and then getting people, not to say, well, we have to, like write the story for everybody, right? But to inspire people to say, "Well, here's the goal, now you figure it out. What does this mean for you and your community?" in a way that's exciting and inspiring. I think that becomes for me, I think of that as imagination is this shared practice. It's a thing we do together as humans. And so how do we set the ground for that? How do we foster, cultivate, support that kind of shared imagination?

HJ: So thought shared imagination is not just U.S. based, but global, I think I'm struck Sarena by how many translations your press has been involved with in this space. So where are some of the other hubs of this dialogue? Where else in the world are people taking up the call of solarpunk and trying to contribute to this conversation?

SU: So, we have to start this with a shout out to Brazil, because they were the ones that created the first solarpunk anthology. That's the one that you mentioned, my small press had translated into English so that it could be part of this conversation. And it's a really interesting collection. I think most of the stories don't quite fit what we would call solarpunk now, they're, a lot of them are pretty dark, and they highlight, just because a corporation is green, that doesn't mean they're not still an evil corporation. But they're really good stories. They're a really good glimpse into speculative fiction from a part of the world we don't see much in translation from. And I don't know if Brazil is really producing a lot of solarpunk now, they might be, but from what I understand, there's a lot of innovation going on within Brazilian science fiction, like they just they love the punks, they've got all kinds of new punks that are very like Brazil-centric. And hopefully, we'll see a lot more of that going global at some point. But in terms of the other countries, Italy is a large one. That's largely thanks to Francesco Verso sorry, Francesco Verso, I probably still mispronounce it, who is, he's translated a lot of solarpunk fiction into Italian and has really just been a big voice for the movement worldwide. But also in Italy, people like Commando Jugendstil, they're an Italian collective of artists and writers. I published two of their stories in my Glass and Gardens anthology, but they've been doing a lot of really cool stuff with both artwork and fiction, in Italy. And then, with the Multispecies Cities anthology, we tried to, we centered Asia Pacific region, partially because there hadn't been a whole lot of those voices involved in solarpunk conversation. So the Multispecies Cities anthology is not exclusively Asian and Asian American, but it is majority Asian and Asian American voices. And we made that decision about two years ago, but it seems like even more important now, in light of the rising hate crimes against Asian Americans that we're elevating these voices, and showcasing better futures, that are free of that type of violence. So it's just interesting how the world and fiction are interact that way. But yeah, Australia has also been pretty well represented in solarpunk. I think there's a lot of, a lot of Australians seem to be very, very aware of immediate climate change issues.

EF: Yeah, my sense is that there are a lot of parts of the world where solarpunk doesn't really have to be a reaction to an overbearing, existing, sort of Western superstructure, because, you know, that never got built in the first place, right? And there's much more openness to say, well, we don't have to work through 100 years of industrialization, and all of the problems that that came with that we just need to live in the world now and adapt to conditions. We still have to deal with all the problems that that industrialization is causing us, even though it happened in other places and benefited other people, but, I think there's an openness. And in some ways, I'm speculating a little bit here, but my sense is that it connects to more traditional values and approaches of like, "Well, what does it mean to be in a community? How are we responsible to one another? And, how do we make things and care for our things?" You know, that solarpunk is not necessary, necessarily revolutionary, it's just something that makes sense. And it's a way to, it's just a different lens to talk about practices that people might have been doing for 1000s of years.

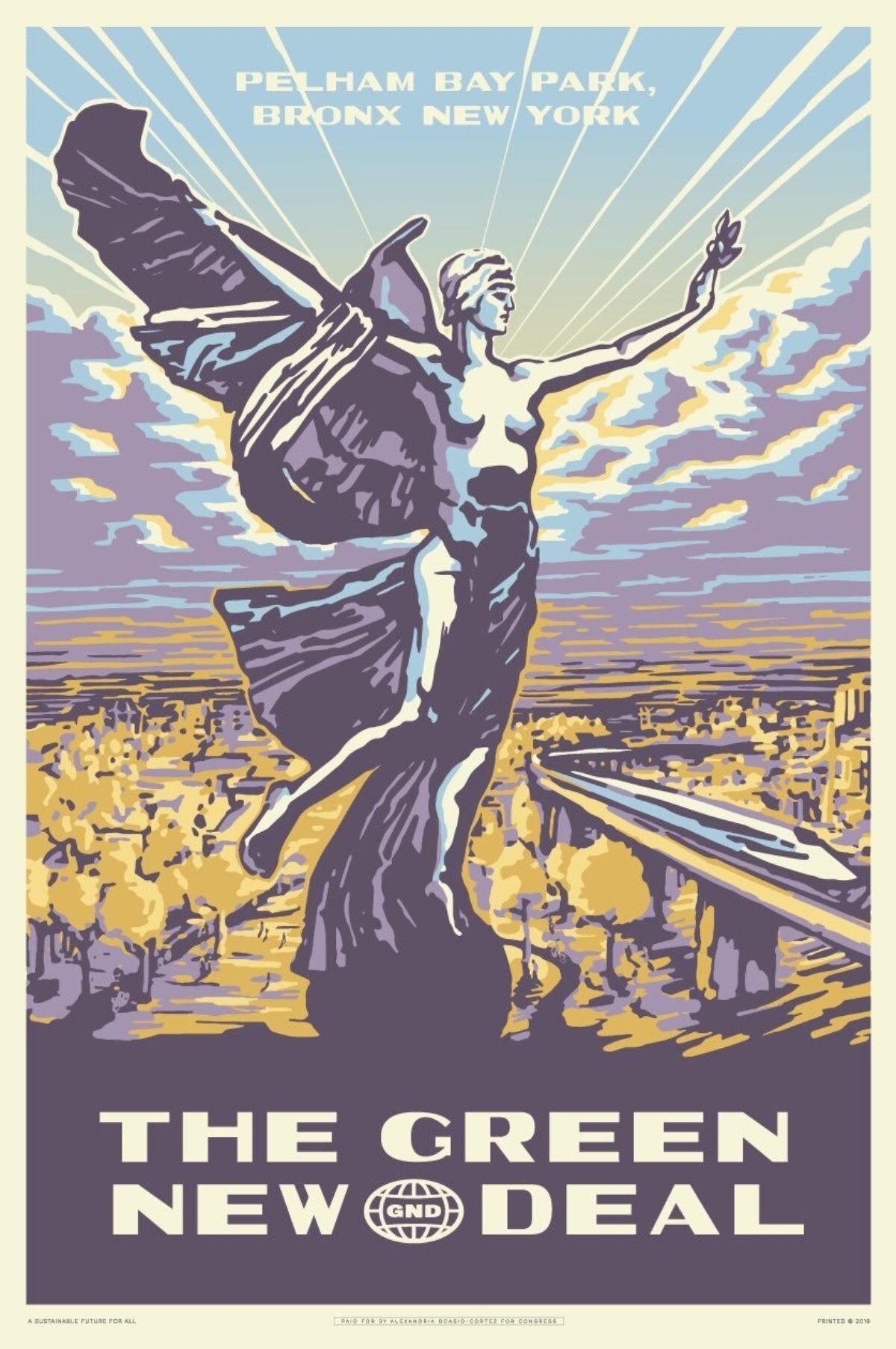

HJ: Is AOC, a solarpunk writer that is, can we think of something like the Green New Deal, and particularly the way it's being promoted actively through speculative storytelling, as a political outgrowth of the solarpunk movement? Or is that going too far, in thinking about what solarpunk is?

SU: I would say, yes. I think she's very much a solarpunk storyteller. And the Green New Deal is a sort of solarpunk imagining, and, to quote, I believe it's Jay Springett, who is a solarpunk writer, that "solarpunks can only be in dialogue with each other. And occasionally in chorus," is something like what his quote is. Meaning, there are plenty of people within the solarpunk community who are not entirely on board with the Green New Deal and who, you know, rightfully, point out some of its limitations and all that. So it is not like the epitome of a solarpunk, you know, policy, but, is it moving the trajectory of the world in a more solarpunk direction? I think so.

EF: Yeah, I think that I agree, radical change is possible, big changes are possible. And it's okay to talk about big changes. I think those are, that's a shift in registers, that was unimaginable, I think, two years ago. I was really struck last year by these huge aid packages that everybody was on board with, you know, the republicans in Congress, being totally on board with these massive, federal investments and giving everybody a check to support people during this incredibly hard year. And even a couple years ago, that would have been pretty unthinkable. So I think that the idea of change is something that everybody is a lot more open to right now. And that we can collectively imagine better futures. And not just do that as an armchair exercise, but actually try stuff and make big bets. You know, try big experiments, that feels like a shift, you know, that feels like a radical break, caused by all sorts of things, political, environmental, you know, epidemiological, and we have to make the best of it, right? We have to we have to try to address these challenges while we have the chance.

CM: Well, you have given me at least a good deal of hope about our capacity to address these challenges and some of the practices and, and ways of engaging that will help us on that journey. So I appreciate you joining us today. It's really been a great conversation.

HJ: Yes, thank you so much!

SU: Thank you. This was great.

EF: Yeah, thanks for having us, this was awesome.

HJ: So a few weeks back, we had the folks from Pop Culture Collaborative on the show. And it strikes me that solarpunk is just a fabulous example of what they're describing as narrative change. That is, this genre that has emerged from a social political need to think about sustainable futures has spread outward in a variety of different directions. But it is designed to have us think about better futures, to dream bigger, to use narrative as a tool, as a way of getting people to think differently about the world they live in.

CM: I mean, I was talking to my kids last night, who were saying something about how the future was terrible, and the planet was going to end, and we were all going to die. And I immediately came to solarpunk. And I said, you know, actually, that's not - I felt obligated just, first of all, to acknowledge that that doesn't have to be the future, that we can think about the future and other ways. And I realized how from, you know, from Hollywood, and kind of big picture, narrative change, all the way down to how we interact with our communities, that sort of optimism and the freedom to think of futures that are appealing. And as we heard, beautiful, right? And this whole, the notion of solarpunk that it is this chance to change how we think about our futures and to imagine the futures that we want, and to imagine beauty in the futures and inclusivity. And many of the vestigial and ongoing challenges of our age. But to reimagine those, and to speculate then on how we get there.

HJ: And part of what I love about it, is that it's a global conversation. So we're bringing in Brazil and Australia and Japan and Korea...

CM: Italy

HJ: ...Africa, into this question about a sustainable future, you know, and it's emerging at this moment where Trump has pulled us out of the global Paris negotiations on the environment.

CM: And what I like about all those different perspectives is, one is, it sort of implicitly pushes back on this notion that efficiency is going to win, and bigger and better. And we need a global solution, but to acknowledge regional, national, local, very local solutions to our challenges, and also allows those many different cultures, both in those particular countries and within those countries, to imagine the futures that they want, right. So it doesn't have to be one big future that we all agree on, but rather that it can feed from many different traditions and cultural contexts and different ways of living. That which, on one hand is more inclusive, because people can see themselves in that future. But it's also really fun for the rest of us, in the same way that we'd like food from all over the world, to imagine these futures and these ways of creating them, that are based on different sets of practices and dynamics. So that to me just feels infinitely more generative in terms of the possibility set of what futures and elements of our futures could look like.

HJ: Well, I think there's a fascinating trajectory to be drawn from the punk rock movement, which comes out of Reagan's America and Thatcher's Britain.

CM: Right.

HJ: And is angry as hell, right? To cyberpunk, which has a certain ambivalence about technological change, and progressively became more and more rancid, in its vision of the future. And at once embraced the integration of human and machine, the cyborg identity, so forth, but then, at the same time, was horrified by it. And it's that push-me-pull-you around technology that it sought to express.

So then the steampunks say, "Wait, we've got to go back and reclaim the beauty of the machine and our relations with it," but go back to the steam snorting era of the past, which is precisely what the cyberpunk creators were trying to push back against. So they designed alternative paths. But solarpunk now is designing alternative futures and holding on to the beauty that the steampunk creators embraced. But doing so in a way that is high tech, low tech, but above all, integrating nature and machine together in a new way. And what's striking about all of those movements is that they are artistic movements, not just literary genres. Each of them in their own way became spread across all of the arts, painting, music, fashion...

CM: Furniture, everything!

HJ: ...by those different aesthetics, you can hear it in the music associated with each of those movements. There's an anger to cyberpunk music, there is a quirkiness about old, creating your own inventions for steampunk music, and there's a kind of new age, natural integration that goes into solarpunk music. So all of that comes together. But each of them are both DIY in one way or another. Maybe steampunk the most, in that it really was inspired by a few books, but was built ground up by the fans, through cosplay, and maker culture, and so forth. But solarpunk is not far behind in that, and each of them, because they have a distinct attitude toward the machine and society, have become activist movements as well with again, solarpunk, maybe, in the clearest trajectory toward narrative change that starts with speculation ends up in activism.

CM: And I love how, I mean, that was an amazing description of those different movements, and really interesting to think about how they're responding kind of as you observed with the original punk, to different elements of their time, right, in different sort of what's happening then. And so what we heard in the conversation today was that what made it punk was taking back control of products, in some sense, right, regaining control, which also takes us back to Cory Doctorow's book way back when? A natural feature of our world today around technology, and the DIY-ness of it, right, so some of these things, DIY, have endured over these different movements, and others may be responding to the political leadership or what's happening. And now you have the, as you note, the environmental piece, right, which, even though the climate crisis has long been happening, we're maybe now reaching fever pitch. So you see that being baked in more deeply to the movement. So I love that, you know, maybe the shared DNA mixed with the new elements of the day that that really do respond. And I think that, it seems to me that both the that backbone, along with the adjustments and additions of today's concerns are what make it so relevant, right? What make it speak to us now, because it's speaking about the worlds that we're inhabiting, and the worlds that we could be inhabiting, in a way that's very, you know, that's palpable. And hopefully, that's actionable, right? Where we feel like we can make a difference. And to me, that's, that's tremendously exciting.

HJ: You know, and I think that we, if there's one strand running through the last eight or nine months of, you know, last two seasons, really of this podcast, it has been the power of speculation going back to the stuff we did, you know, at the beginning of the pandemic, were science fiction writers, like Bruce Sterling and talking about Japanese... But that was a darker speculation.

CM: Yeah.

HJ: Now, as we're in the Biden era, and we're looking at maybe some end of the pandemic, it's now time to think about how do we build back better, as Biden would put it? Or how do we talk about what we want rather than what we don't want as our guests put today? Or how do we extend the horizon to tell the story of climate change, not in that news frame, that is so hyper, located in time, as the way we talked about it last week. So the theme of speculation, I think's become an important one. After all, how do we like it so far? What's coming next, as a phrase?

CM: Well, speaking of what's coming next and speculation I am, I could not be more excited about our next show when we're gonna have SB Divya and Jonathan Keats. So we have, Divya is a science fiction writer, solarpunk writer, scientist, and remarkable thinker about the future. And Jonathan, as an artist, I think he calls himself an experimental philosopher, among other things, and author, really has done remarkable thought experiments that change your idea about as with Divya's work about what, or challenge your ideas about what humans are, about time and how we think about time and the nature of time. So I'm really excited to continue this, our own speculation about speculation.

HJ: It's gonna be fun.

CM: So next week we're going to continue building on these themes with SB Divya and Jonathan Keats. Divya is a scientist and engineer, and author and editor, recently has a great book out called Machinehood, and other solarpunk things in the works and out there. And Jonathan Keats is an experimental philosopher, author and just troublemaker.

CM: This show could not happen without our amazing production team, which includes Josh Chang, Sophie, Madej and Alexander Yeh. They are all amazing and the core of our enterprise.

HJ: We also thank University of Southern California Annenberg School and the MacArthur Foundation for their support for our activities, even though we're no longer recording out of the wonderful studios at Annenberg, but are recording wherever our laptop happens to be at any given moment in time.

CM: And most of the time, we are here in Los Angeles, like the USC campus, which rests on the historical lands of the Tongva and Gabrielino People and we appreciate their stewardship. In addition to finding us wherever you find your podcasts, we are on the web and howdoyoulikeitsofar.org, all one word as it were, and on social at H-D-Y-L-I-S-F, both on Twitter and Instagram. So check us out, say hello!