"Wish You Were Here": Imaginative Mobilities and Disembodied Intimacy in Postcards (Part One)

/The following paper was written by Sui Wang, who was a student in my PhD seminar on Media Theory and History last fall. I was impressed by the lyrical quality of her writing and the multiple perspectives she brought to bear on the postcard, a medium that has rarely received critical attention.

“Wish you were here”: Imaginative Mobilities and Disembodied Intimacy in Postcards

by Sui Wang

Abstract

The postcard is a rich medium inscribed with entangled relationships. As a commodity, it circulates between publishers, buyers and collectors. As an emerging communication technology, the advent of the postcard caused many to reconsider previously held understandings of concepts such as intimacy and privacy at the turn of the 20th century. It mediates the distance with romantic intentions and facilitates virtual, asynchronous encounters. The handwritten messages on the recto grant glimpses into, despite its brevity, the relationship between the senders and receivers. On the verso, they have photographs or color fine prints that depict historical places. It is imperative that we understand the boom of picture postcards within the context of both the technological advancements of the era such as photography and color lithographs and the growth of the postal service. It is also important to contextualize and historicize it in the genealogy of epistolary communication, for instance, how it remediates some elements of letters and how it is remediated by the message apps of today. A re-examination of this technological history bespeaks a disappearance of tangible artifacts, by which correspondents conceive the virtual presence. This essay adopts a bifurcated method combining close readings of textual and visual messages on postcards, on the one hand, and investigations of its representational nature and materiality vis-à-vis the technological infrastructure, on the other hand. Drawing on postcards from the early 20th century and literary examples, I argue that picture postcards depict a central tenet of epistolary communication, namely, the process that the immaterial bodies of senders and receivers, as well as of places, are imagined through reading and writing.

Introduction

“I am a visual image and made on paper. I embody the intention of the sender and the pleasure of the receiver. I tell small stories of travel; the joy, the hardship, the movement, the ticketing, the comfort, the discomfort, the lost luggage, the lost time and the stories of cities with their own peculiar rhythm. I register the spectacle and the viewer, held in place by the click and aim of cameras, destinations with their promise of something other than the known and events that may take you out of your comfort zone, even speaking of love. I carry words: ‘I’ve been in Greece for only a few days (fell in love with it)’. My action is embodied in acts of communication, I reveal fragments of stories that are personal representations of places and people, and I accumulate in a range of storage containers and in displays. I become a collection, which resembles elements of narrative. I constitute a memory archive and can prevent forgetting. I can be read in different ways by the interested and the disinterested (219).

— “The Postcard: The Fragment,” Rosslyn Prosser

Postal historians date the genesis of postcards to the late 19th century, while its precursor had appeared in various forms of card-with-messages: visiting card, pictorial notecard, decorated envelop and the carte-de-visite. Despite the slightly different social protocols developed around them, they share a similar format (pair of text and visual) and were invented to facilitate the epistolary communication. In the 1860s, Postal Director Heinrich von Stephan pioneered the postcard in Germany for the sake of efficacy and convenience, arguing that the present form of the letter did not show sufficient simplicity for “a large class of communications” hence needed to be updated. “It is not simple enough, because note-paper has to be selected and folded, envelopes obtained and closed, and stamps affixed. It is not brief enough, because, if a letter be written, convention necessitates something more than the bare communication.” The early backlash primarily centered around the loss of epistolary privacy and possible censorship. The public nature of it, which was counter to our assumption of epistolary communication, fostered people’s hesitance to embrace this new medium. When it was eventually implemented later, it was used mostly in realms of military correspondence and business communication, very rarely intended for love and family letters. Even so, The 1869 Post Office Regulation still stipulates that “the Post Department will not be responsible for the contents of the message… Nevertheless the post offices are instructed .… to exclude postcards likewise from transportation and delivery, if obscenities, libellous remarks or other punishable acts are found on the cards.” The field postcards during the Franco-Prussian War period were undecorated and designed with fixed forms that only conveyed basic information, such as name, place, and sign of life.

In the late 19th century, postcards and the postal systems were introduced to most of Europe, the United States and Australia. The design of the postcard also went through different stages as it gradually transitioned into picture postcards of today. In the undivided-back phase, people could only write addresses on one side, and brief messages on the margin of the picture side. Some pictures were printed in a way to accommodate the messages. The contemporary postcard resumes “divided-back” format, where the torso of postcard is divided into two spaces, for correspondence and address respectively. The craze for postcards swept Europe and the United States at the turn of century, concurrent with the booming of mass tourism and international postal service. It is estimated that around 200 - 300 billion postcards were produced and sold during this time (Rogan 1). Postcard mania did not discriminate nationality, class, age or gender. The postcard as a visual medium was also conceived as a popular art. The postcard introduces a new paradigm of epistolary writing, which upholds the economy of words and democratic colloquialism. As Milne aptly puts it, “perhaps for the first time the postcard made visible the discursive practices of the general public. The texts of ‘the everyday’, the products of ‘ordinary’ writers, were now being circulated and read in a manner and on a scale that had not previously been possible (117).” Postcard senders squeeze their travel stories, homesickness and fleeting feelings of sceneries into several sentences within the limited space on the verso, expecting the addressees can at least capture some of it when they receive that stamped paper with smeared postmarks and scribbled handwritings.

A postcard travels. It not only travels from place to place, but travels between private and public spheres as well. The postcard is originally addressed to a specific receiver as a personal correspondence, while it ends up circulating semi-publicly from the hands of publishers and postmen to receivers and collectors. It is the semi-public circulation of postcards that makes us reconfigure privacy and intimacy in the changing contexts and differing socio-technical relations. “Aesthetics and communication, ritual and symbol, technology and business, play and action, imagination and remembrance, desire and materiality, commodity as well as subjective experience (Rogan 3),” the postcard seems to integrate all these aspects into a snippet.

Art historians tend to attach unbalanced emphasis to the pictorial side of postcards. Viewing it as “a sign of time”, scholars ascertain the history through the visual representations of places on postcards. The picture postcard acquires the documentary role of photography hence replicates its controversies. Photography eventually denies the wishful positivistic thinking of the transparency of this medium. The archive of picture postcards embodies visual coloniality, with the cards exhibiting the exotic and creating stereotypical topography. Earlier as an attempt to examine the “scientific” history, the interpretation of pictures/photographs gradually turns into revisionist revisits. While the picture side seems to provide a fascinating arena for studying visual history, this should not eclipse the other side, in which the public image is annotated with private information. In order to understand the entangled nature of postcards, I propose to read both sides in relation and examine the private-public negotiation at the nexus. This essay will adopt the Lury and Lash’s method of “following the object”, and tracing the cultural biographies of postcards to further investigate the multi-modalities and discursive practices it engenders.

Imaginative mobilities: “wish you were here”

Inextricably tied with tourism, picture postcards have always been a medium for travelers. At the beginning of the 20th century, urban tourism rose in popularity in the United States. City tours and factory tours became a trend among the leisure class. The developments of transportation networks, the travel industry and lodging facilities later lowered the cost of travel and promoted travel as a lifestyle for people of a wider range of classes. Industrial towns and factories embraced tourism as a means of advertising and published picture postcards for the branding effect. Marketed as souvenir cards, picture postcards were ubiquitous in tourist attractions. Writing postcards was equivalent to the present day ritual of taking pictures and the postcard a possible precursor to Instagram post. Travel accounts of the early 20th century demonstrate the fad of writing postcards among travelers:

Figure 1. Easton's Point, Newport, Rhode Island, circa 1901-1907. Postmark date: May 18, 1907. From National Trust Library Historic Postcards Collection.

“When I entered the hall with all the interesting Nordic wooden carvings, I found the room filled with people, who without exception sat writing. And what did they write? Picture postcards!! Oh, scourge of all scourges in this century. Like a pest you have fallen over us, and you pursue us into the most desolate valley. No one is safe from you. You are capable of spoiling the most beautiful voyage, the most picturesque landscape, the most serene fjord, the highest lookout point. . . . And what does the tourist do, when your call wakes him up from his silent contemplation of nature? . . . He digs deep into his pocket, brings out his purse and buys, more or less grudgingly, 2, 4, 6, 10, or 20 postcards, according to the number of friends and family. Instead of enjoying the marvelous view of the landscape . . . the tourist sits down and with an unusable pencil scribbles some unreadable lines (Laverrenz 60-61).”

Rather than “silently contemplating the nature”, travelers turned their eyes away from the “marvelous view” and buried their heads in writing the postcards, whose pictures, though highly idealized, became the tangible substitutes for the real views hence the authentication of travel. The former benefits the receiver, while the latter matters more to the sender. Postcards create the need to share the views during travel and, probably in a remote sense, mitigates the solitude of travel. Like other forms of entertainment, tourism celebrates togetherness. Despite the fact that the materiality of postcards often authenticate travel, the overabundance (instead of flourishing) of postcards can jeopardize that authenticity. Scholars like Cure brought awareness to this issue, arguing that “…despite the inherent role of media in performing travel, over-mediation threatened to obscure the immediate experience (689).” Invented as a cheaper substitute (than photography), pictures on the postcards soon, took over the landscape itself. A Britain cruise tourist concluded that “tourists no longer needed to remember the views and places visited—it was sufficient to bring home the postcards (Rogan 10; Klinghammer 1903).” Compared to the physical evidence, the real experience of travel appears fleeting thus tenuous. Similar stories are happening in the era of social media. Our travels are increasingly mediated by Instagram posts and organized by the Instagrammable spots. The postcard cultivates the virtual travel culture, which by extension foresees the simulacrum and art reproductions. It also offers a productive site for “contesting valorizations of authenticity and imitation” and analyzing the duality of “immediacy” versus “hypermediacy” in Bolter and Grusin’s terms (Cure 1050).

Further investigations into the authenticity in relation to postcards would require a close scrutiny of its modalities. When Walter Benjamin lamented on the loss of aura in his monograph, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” he argues that the reproduction of art work dissolves the “aura” of original work in removing its distance from viewers. In the case of postcards, the “distance” is maintained through the travel of postcards and the lengthy time it would take. It also preserves the “aura”, or the sense of being here/there and now/then, via the personalized textual messages attached to the images.

Based on my research on postcards from the National Trust Library Historic Postcards Collection (circa 1900-1920), most of the texts are about their travel stories with regard to the place, lodging and weather. They also include messages like “thinking of you”, “wonder what you are doing”, “will be home soon” and the like. For instance, this postcard from Rhode Island in 1916 reads: “Dear Mal,

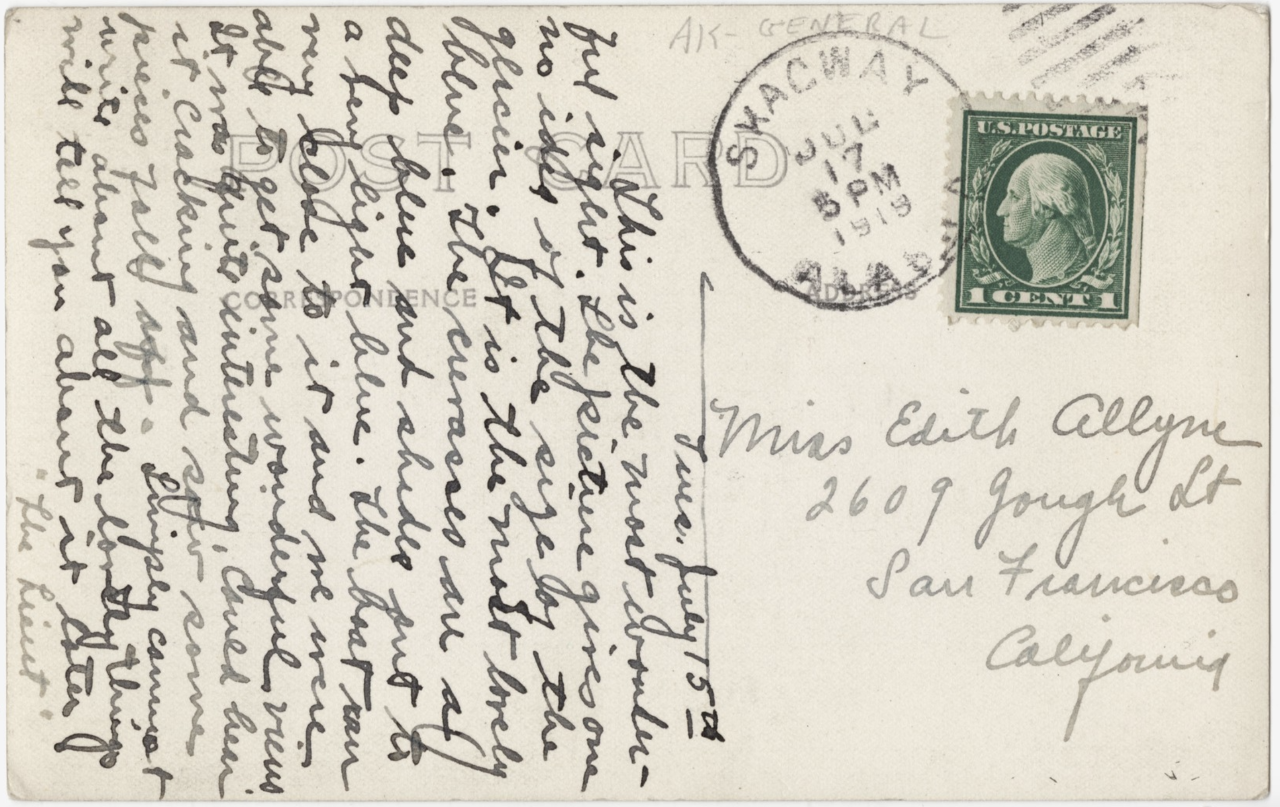

Figure 2. Taku Glacier, Alaska, circa 1907-1914. Postmark date: July 17, 1919. From National Trust Library Historic Postcards Collection

We arrived hear [sic] tonight but I couldn't get ashore until half past seven and I didn't moor [sic] as you would be at home but will be in again soon.

From H [?] Northport, yacht Robin Maine.”

This Mr/Ms H shared his travel anecdote and communicated a sign of his safety in roughly two sentences, plus, he also expressed the expectation of “being again soon”. Some postcards are even more concise. A postcard from Santa Catalina Island in 1906 reads: “This is where I spent Labor Day. Elmer.” The pithiness makes it hard to read much more into it. There is little for readers to infer from. Östman contends that “postcards have a particular rhetorical structure.” Besides the recurring elements like name, address and greeting, the rhetorical elements and the order of them vary from culture to culture. The elements may include “reference to the picture, weather and circumstances, foreign language, reference to the workplace, greeting and leave-taking (431).” A closer look into the texts on postcards reveals more semiotic and linguistic patterns. The texts on postcards are often of conversational language and exhibit dialogism markers, such as questions, responses, pragmatic particles and emotional markers (433). Figure 1 is a fine-print postcard with blue ocean waves picture. Rob was sharing this nice surf view with Agnes when visiting Rhode Island. The language is succinct, simple, even somewhat poetic. His greeting conveyed a sense of lightheartedness and intimacy, which naturally evoked speculations on his relationship with Agnes -- are they lovers? What does he mean by “Your moonlight view was a ‘beaut’”? This kind of inside joke is very typical of postcard writing. The messages are often coded in a language between the senders and the receivers, which effectively hinders the voyeuristic reading from the unintended readers like postmen or family members who happen to pick up the postcards. It could be also considered as a linguistic strategy to counter the loss of privacy, or to deal with the unavoidable semi-publicness of postcard. What makes sense to the receiver may not make sense to another person at all. This phenomenon echoes the “context collapse” on contemporary social media - the interpretations of information are highly hinged on the different social contexts people are making sense of under. “We live in a world where there is more and more information, and less and less meaning (McLuhan and Lapham 6).” The context that confines the meaning-making indeed carries the performances of social identities. On the contrary, the postcard is inherently fragmentary and anti-context.

Dear Agnes: Have you any nice surf views. I should like very much to have some. Your moonlight view was a "beaut” Rob. my boat

“This is the most wonderful sight. The picture gives one no idea of the size of the glacier. It is the most lovely blue. The crevasses are a deep blue and shades out to a very light blue. The boat ran very close to it and we were able to get some wonderful views. It was quite interesting. Could hear it cracking and saw some pieces fall off. Simply cannot write about all the lovely things, will tell you about it later.”

In Figure 2, the sender wrote what they saw in eidetic details, for instance, “deep blue and shades out to a very light blue”; his words are brimming with excitement and sublime feelings towards nature, but simultaneously emphasizing the disparity between the represented view and the real view: “the picture gives one no idea of the size and the actual color of the glacier.” They went on to add sonic information that the image simply cannot include, i.e. the cracking sounds of ice. Lastly, the sender, again, questioned the expressive capacity of the postcard and concluded with “will tell you about it later.” This postcard perfectly demonstrates the trope of “wish you were here” that encourages the receiver to imagine a shared presence through reading the visual-textual messages it contains. However, it also indicates that the shared presence should only be imagined in a mediated fashion. The way to bridge the gap between the image and the glacier, as the sender stated, is physically being together and “tell you all about it.” A postcard like this thus retains the aura and romanticizes the distance between them. For the receiver, it kindles the hope for their next meeting and makes the time before it bittersweet. According to Milne, the “absence” here is creative; “it opens a discursive space in which desires and subjectivities that might not otherwise be articulated can be explored. (5)”

Andriotis and Mavric examined the postcard under the Urry’s “the New Mobilities Paradigm (NMP in short)”, namely “corporeal, imaginative, communicative, virtual and the mobility of objects, and systems supporting them, which in turn produce and sustain social lives.” In light of the communicative and visual properties, they view postcards as “representing virtual mobility of the time (19).” I argue that the postcard produces “imaginative mobilities” for the viewers. According to NMP, “imaginative mobility is triggered by images (and texts) circulating through print and visual media.” Through reading the postcards, the addressees not only imagine a shared presence, but go on imaginative travels to afar places. For many of them, the postcard is likely the only way to encounter faraway places. The aura, embodied in the distance between senders and receivers, between real views and represented views, enhances the imaginative mobilities provided for virtual travelers. What is more important are the personal touches to the imaginative mobilities embedded in the postcard messages. The strange places are brought by familiar people. The personal/impersonal duality keeps paralleling the private/public binary among the discussions of postcards.

MORE TO COME

Trained as a media scholar and a journalist, Sui Wang’s work explore the media history of modern China and Japan with focuses on visual culture and sonic media. She is a second-year master student in East Asian studies at University of Southern California. Currently, she is working on her master thesis, which investigates how the listenership of overseas Chinese radio stations makes their diasporic identities. In her leisure time, she loves rewatching Chris Marker and writing short stories in Amazon reviews. You can read more of her other work at www.suiwang.org