Global Fandom Conversations (Round One): Bertha Chin, Lori Moromoto, Rukmini Pande (Part Two)

/3. To what degree do fandoms still reflect local cultural traditions and practices?

RP: I think this is a very broad question that could have radically different responses. I’ll take this opportunity to reflect on a trend that I’ve noticed amongst transnational fandom conversations over the last few years. This encompasses parallel processes of othering and simplification that take place when discussing specific cultural issues reflected in non-anglophone media texts and their fandom communities.

The process of othering is perhaps a familiar one to most scholars. It happens when certain practices specific to those fandoms - pertaining to fanart, fanfiction, etiquette around creator contact, etc - are seen as “problematic” by fans unfamiliar to those milieus. The resulting critique can also impose un-nuanced ideas around identity and representation. This is obviously a troubling phenomenon and is rightfully pushed back against by fans who see it as a misrepresentation of their own specific fan practices as shaped by local histories, cultures, and even pragmatic considerations around access and legal issues.

However, perhaps inadvertently, this pushback can also result in what I term as simplification, whereby complex political, social and cultural issues informing those same specific fan practices are flattened out in order to be championed uncritically. In such cases, even fans speaking from positions of knowledge and experience within those fandoms are branded as “outsiders.” No media text or fandom is free from issues and hierarchies of power around representations of identity, relationships, and desire. Fans wanting to defend their localized practices against casual dismissal are extremely valid, but I find that this impulse also often undermines location-specific critiques which is an added layer of complexity.

BC: In my opening statement, I alluded to the 'cultural baggage' of conflict and reluctance, and at times, shame, when I looked at the way fandom is discussed in Malaysia. Commercially successful franchises and media such as the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars, Game of Thrones, and most recently, BTS and Squid Game are considered acceptable, often serving as fodder for national conversation. It is one thing to be able to understand the latest superhero references in popular press coverage, or to purchase a Funko Pop figure but fans are still cautioned against being too emotionally attached to a media text. My conversations with students certainly reveal this contradiction, where pop culture knowledge is considered "cool", but fandom is often "waste of time" and something one does as a child (and thus, grow out of). The hierarchy of taste is delineated along commercially successful texts, and acceptable fan practice is sanctioned by the industry through consumption of official merchandise. Any other fan practice that falls into a more transformative pursuit is othered, and often simplified, not only into “fluff”, but “fluff” that is a cause for concern.

It is difficult, at this juncture not to recall a friend's question, early on in my PhD, as to why I was researching fan cultures and not something "more serious", and that "Asian people don't do fandom". There is always a sense that fandom is a 'foreign practice' within Southeast -- and East -- Asian scholarship, which speaks to Lori's point about the devalued nature of Fan Studies within the academy. Except when one is of Asian descent, this scholarship is devalued twice over, within the academy and among fans themselves. But given Southeast Asia is itself a cosmopolitan hybrid of identities, it is difficult to determine what is local, and as such what would then be considered as ‘authentic’.

LM: At the risk of continuing in a contradictory vein, “local cultural traditions and practices” is also something that I would problematize insofar as, to paraphrase Rukmini above, it can mean “radically different” things to different people. Historically, hegemonic fan studies has conceptualized ‘local’ fan traditions and practices in opposition to normative fandom practices; that is, as discrete and located outside those practices and traditions that characterize ill-defined (but seemingly universally understood) ‘fandom’ and ‘fan community’. There is little sense in lambasting foundational scholarship that originated and upheld such characterizations, particularly inasmuch as it was a product of its moment in both the history of media fan practices and the evolution of fan studies. But in our current media fandom/fan studies moment, I have a first-row seat to vitriolic English-language debates on social media about the in/validity of fujoshi (lit. “rotten women,” referring to women who consume and create Boy’s Love and yaoi media) that are entirely divorced from - and wilfully uninterested in - their original Japanese contexts. I’ve also gotten my feet wet in that Anglo-American iteration of Chinese drama fandom spawned by the increasing ubiquity of Mainland Chinese dramas on such mainstream streaming platforms like Netflix, YouTube, and Amazon Prime, where we struggle to grasp both the minutiae of Chinese* fan knowledges and practices (kadian, anyone?) and, in particular, the complex social and political circumstances that led to, among other things, English language fanfiction stalwart Archive of Our Own being banned by Mainland Chinese authorities.

Within this context, what is “local” and against what are we defining it? For example, as I have argued elsewhere (Morimoto, 2019), Archive of Our Own has quite specific cultural traditions and practices that aren’t necessarily generalizable to English-language fanfiction reading and writing practices on FanFiction.net or Wattpad; can we then consider AO3’s norms ‘local’ (in opposition to those fans for whom AO3 embodies fanfiction culture, to the extent that it’s even recognized as a part, rather than the whole, of ‘fandom’)? Or is there perhaps a better way of conceptualizing both the vast array of fan practices and traditions enacted globally, as well as what happens when contact with other practices and traditions alter, challenge, or otherwise inflect them?

*see Bertha below to fully appreciate the complexity of such a superficially self-evident category as “Chinese fans”

4. What are some of the key issues and challenges facing “global fandom” today?

RP: This conversation has perhaps sketched out some of the key challenges already but perhaps to recap, in my view, the key challenges for scholars of “global fandom” are building theoretical frameworks that can facilitate robust and nuanced examination of complex fan practices. I also think that it is vital to underline that building these frameworks are not abstract practices. They must engage with the increasingly skewed contemporary reality for many scholars - particularly those from the Global South but also those in the Global North with critical accessibility issues - who now face even greater barriers to participation in academic discourse than before. After all, no discipline can claim to be “global” without taking account of the exclusion of so many peers working in those very contexts.

BC: Rukmini makes a really good point about needing more robust and nuanced theoretical frameworks to look at global fandom. Conversations like these are great starting points, and the fact that Henry is hosting them would mean that people would be aware that these conversations are happening, but as Lori pointed out, it's also dependent on the willingness of scholars to read and engage. And I'd like to take this further by saying that we need to ensure that this doesn't just become a cursory nod to acknowledge diversity and inclusivity, but to also pay attention to the gaps and silences, to who is being silenced, and the question of who is speaking for whom. Even -- and especially when -- it doesn't agree with our viewpoints or our understanding of the world. There is a lot of histories that are still being re-written; there are different approaches to, and understandings of postcoloniality, for instance that doesn't necessarily fit into a neat, little box we can place people into, and this informs and affects fans' understanding of their identities and their cultures. Acknowledging the constraints of where the fan scholar is working from, not just within an academic institution, but also the geopolitical location of the fan scholar would continue to be a key issue.

To build on the example that both Lori and Rukmini have already raised, I return to what's happening in China, and the different perspectives that have been offered up as explanations. The English language media in the West posits it as -- to borrow from Lori -- "[X authoritarian regime] cracks down on [Y subculture]", and a 'global event' like this will continue to be a challenge to the ways we conceptualise and understand what global fan cultures is. Even within the different factions of fandoms in China itself, responses and reactions to the crackdowns are varied; just as our reactions, as fan, celebrity and media scholars (and again, dependent on our educational, social and cultural capitals) are different. When I look at what's happening in China, for instance, it's more than just a crackdown on a specific subculture, but rather, it's also a very specific reading of how to perform Chinese-ness on a global scale, as dictated by a powerful country whose people have migrated to other parts of the world for centuries. And yet this performance is rooted in a sense of Confucian morality, and it is a cultural crackdown that can be alarming for other ethnic Chinese, long assimilated into hybrid identities or the culture of their migrated homes, who do not identify with a Confucian understanding of Chinese-ness. In short, it is never as simple or as neat as it seems.

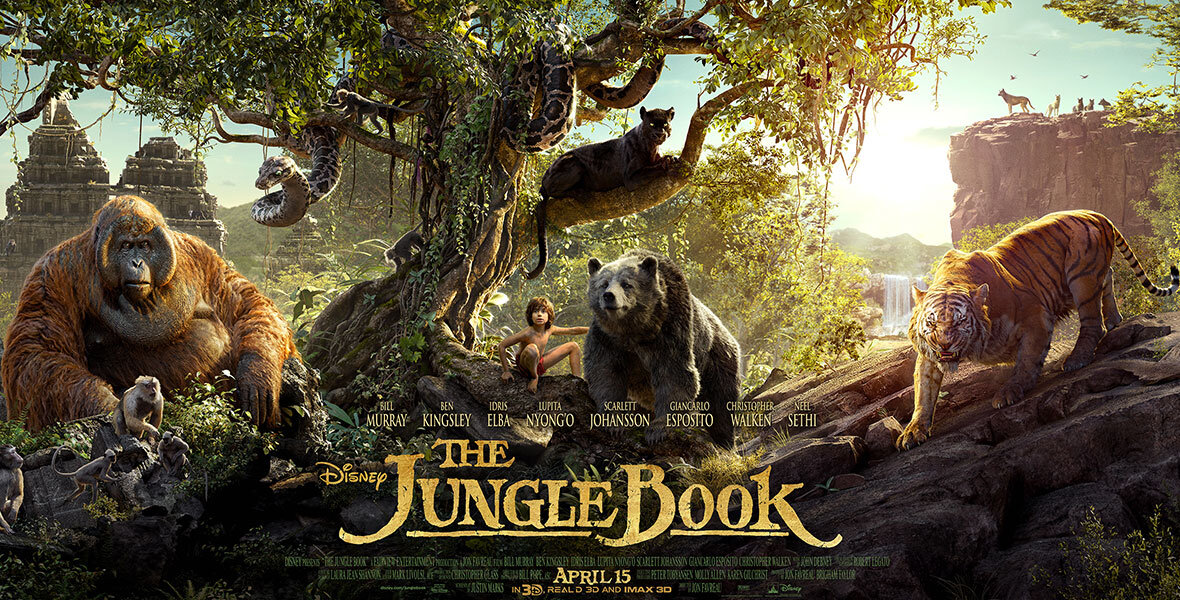

LM: To pick up where Bertha leaves off, I want to tell a quick story that happened over coffee with Rukmini and her friend Swati Moitra during a conference we were all at several years ago (a story I know Rukmini all too familiar with because I keep going on and on about it!). They had followed the conversation into a discussion about the upcoming Indian release of Disney’s live-action version of The Jungle Book (Jon Favreau, 2016), which Rukmini expressed some skepticism about until Swati mentioned a number of the actors involved and, in particular, a song being used in its promotion that updated the Hindi-language theme song of the Japanese anime series, The Jungle Book: Adventures of Mowgli ジャングルブック 少年モーグリ (Kurokawa Fumio, 1989-90). Rukmini ultimately wrote a touching and complex review of the film addressing how this corporate-strategized mashup of Kipling’s notoriously colonialist novel, Indian casting, and use of the widely beloved theme song to its Japanese adaptation effectively enabled a “reclamation” of the text, “expand[ing] into and imaginative space I didn’t quite know existed.”

What grabbed my attention about this, and what I think is emblematic of the challenges facing fandoms and fan studies going forward, is its semiotic complexity. For Disney, a global corporation whose attempts at media localization include the insertion of painfully transparent scenes set in China in Iron Man 3 (Shane Black, 2013) intended to attract “Chinese” viewers (who, it should be noted, saw right through them), not to mention the Southeast Asian rollout of Disney+ Hotstar that Bertha discusses in her opening statement, this strategy seems uniquely attuned to the arguably counterintuitive popular cultural specificities of transmedia Jungle Book reception in India; something that, for being equally attuned to them, Rukmini’s nuanced analysis is able to discern and discuss. At the same time, her caveat that, “I'm not trying to argue here that the text is somehow free of Disney's globalisation agenda—it could be argued to have accomplished that agenda empathically, given that it made the company about Rs 180 cr (the most for any foreign film release in India by far),” equally demonstrates how, as she notes above, simplistic “ideas of resistance, subversion, or compliance” are often inadequate when it comes to grasping transnational and transcultural media fandoms and fan objects in their often-contradictory complexity.

In this sense, and particularly at a time when we must remind ourselves to think before we hit send on social media, when the number of ‘likes’ on our (often-unsolicited) opinions can engender significant social capital, when we jockey for authority in a world that thrusts us into ever-closer quarters with little understanding of how to navigate and negotiate that space, the need to acknowledge that, as Bertha writes, nothing is ever “as simple or neat as it seems” is at once absolutely imperative and a challenge that both fans and fan scholars face going forward.