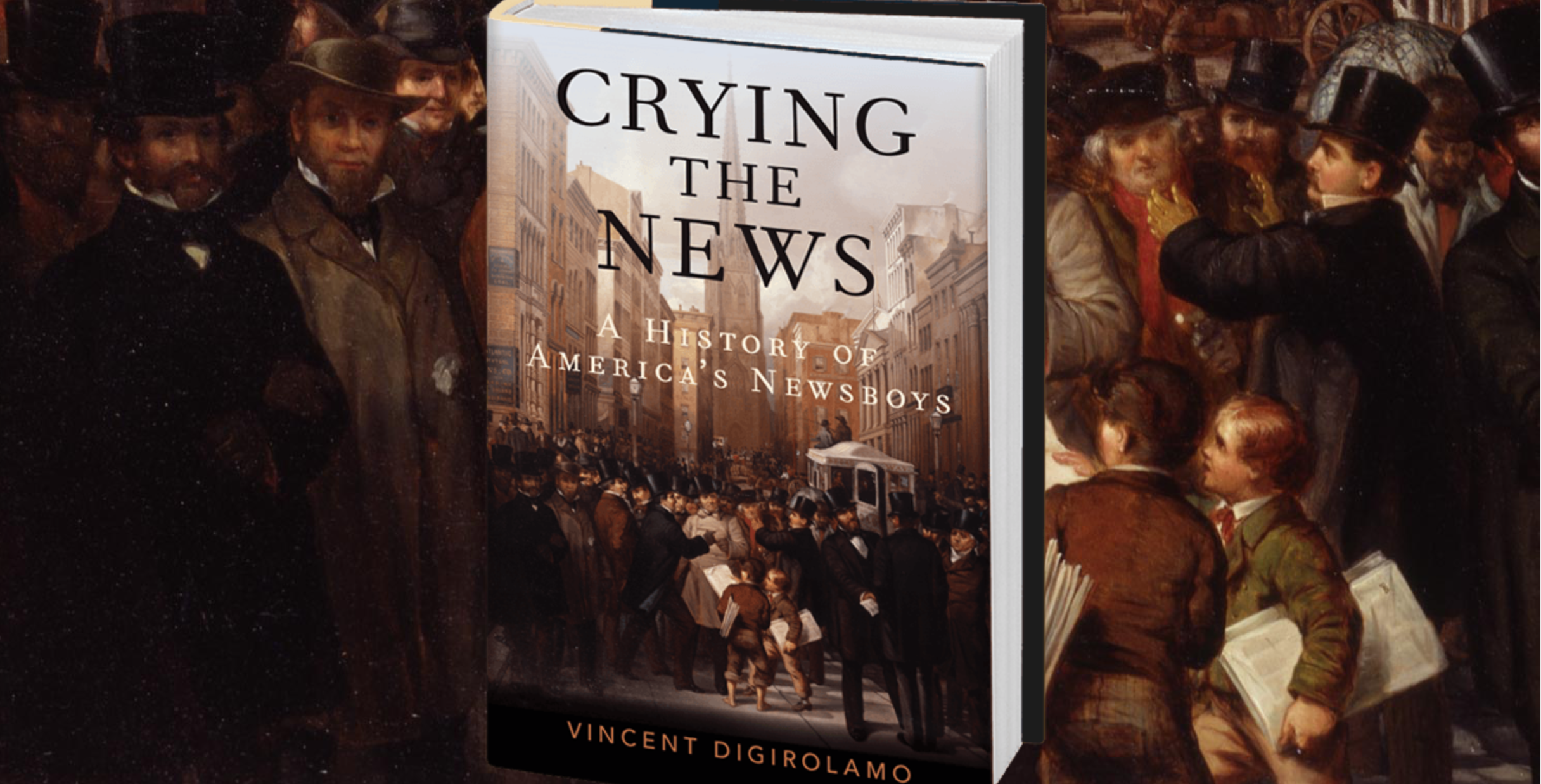

Newsboys in America: An Interview with Vincent DiGirolamo (2 of 2)

/What factors led to the rise of the newsboy in America?

Newspaper hawkers first appeared as a distinct urban type in New York in the 1830s. They were products of the penny press—cheap newspapers for the masses, which were themselves products of the Market Revolution—the commercial expansion of agriculture and manufacturethat transformed the American economy, polity, and culture. Newsboys facilitated the flow of goods and information across the country, and they quickly caught the eye of artists and writers who transformed them into symbols of Young America—brassy but virtuous strivers who were always on the lookout for the next main chance. Articles about newsboys appeared in the new penny dailies and the scandalous Sunday papers and flash press, as well as in Whig and Democratic journals like Knickerbocker Magazine and US Magazine and Democratic Review. They also inspired the vogue for what I call “urchin art”—genre paintings of street children by the likes of Henry Inman, J. G. Brown, and many others. These youths proved useful as workers and symbols.

Were newsboys a mostly urban phenomenon?

Newsboys were primarily but not exclusively children of the city. They also worked in small towns and rural areas, distributing local papers and the big city dailies that were shipped in.

Poverty haunted communities of every size and locale. Sherwood Anderson, for example, grew up so poor in Clyde, Ohio, in the 1880s that he sometimes ate grass. He not only delivered the Cleveland Plain Dealerand Toledo Blade, but he also herded cows, toted water, and acquired, sold, and sublet so many jobs that he earned the nickname “Jobby.” Newsboys also trod the dusty streets and plank sidewalks of western boomtowns, cow towns, and military posts. Some boys serviced their routes on horseback. These kids were key players in the development of the urban frontier because every town needed a newspaper to stimulate settlement.

Boys also worked for the newspaper distribution firms that supplied small towns. These youths folded, bagged, and hauled papers to the railroad depots, or rode the cars and tossed bundles to carriers waiting at the various whistle-stops. Railroads also gave rise to tramp newsboys who hopped freight and passenger cars to work the crowds at horse races, boxing matches, state fairs, and political conventions. More respectable were the uniformed train boys who sold newspapers, magazines, and other items to rail passengers. These “news butchers” represented the aristocracy of newsboy labor, yet many ended up in debt to their companies for unsold or spoiled goods. Others lost their lives in rail accidents. Their families sometimes received compensation, but a common condition of employment as a train boy was to sign a liability waiver. I found that a few girls did this kind of work disguised as boys, but they were promptly fired when their true identities were discovered.

What were some of the risks of being a newsboy and why did they develop such a reputation for being rough and tumble?

Aside from the daily risk of getting robbed, run over, or run off, newsboys had to contend with the ever-present possibility of "getting stuck"— buying more papers than they could sell. Hence their motivation to hustle and shout, “flip” streetcars and dodge oncoming traffic. Progressive Era reformers enumerated the hazards of newsboy life, dividing them into two categories: physical and moral. Physical hazards included flat feet, curved spines, sore throats, skipped meals, stunted growth, and venereal disease. The moral dangers included a propensity to smoke, swear, steal, gamble, fight, drop out of school, and fraternize with hoodlums and prostitutes. Child labor reformers felt that the excitement and relative autonomy of street hawking ruined children for steady work. All of these concerns raise questions about the differences between working-class and middle-class attitudes and values, which I try to examine fairly, without deifying reformers, demonizing publishers, or censuring parents.

One of the first stories you share is about a news boy who jumped the gun on announcing the first shots of the Civil War by almost two weeks. This raises the question of what role newsboys played in the sensationalism of the American press or what today we might discuss as “fake news.”

The fake news of today bears no resemblance to the fake news of yesteryear when it was shouted by hungry kids who knowingly sought to make a few extra nickels by bilking a gullible public until someone got wise and thrashed them for their deception. It was a risky business, good for a fleeting thrill more than a steady income, as it would ultimately lead to a loss of credibility and customers. So yes, some kids falsely announced the sinking of the Atlantic and the murder of General Grant, or prematurely blared the fall of Fort Sumter and the death of President McKinley. It helps to remember that news peddling was a kind show business or street theater. Growing up in Philadelphia, William Dukenfield (W.C. Fields) would juggle rolled-up newspapers to gather a crowd and then invent silly headlines like “Amos Stump Found in an Eagle’s Nest.” It was part of his shtick. Yet newsboys who later took liberties with the facts during World War I faced threats of prosecution under the Espionage Act.

It’s also true that newspapers sometimes printed false news as hoaxes. All journalism students learn about the New York Sun’s moon hoax in 1835. Edgar Allan Poe perpetrated a similar fraud in the Sun in 1844 with a story about a transatlantic balloon crossing. And the New York Herald scared the bejesus out of Gothamites with its 1874 hoax of a mass escape of rhinos, baboons, and jungle cats from the Central Park Zoo. Newspaper publishers usually defended such fictions as satires or entertainments.

More damaging were the sensationalist reports of Spanish perfidy during the Spanish-American War. William Randolph Hearst, Joseph Pulitzer, and other yellow press lords engaged in exaggeration and outright fabrication to bolster nationalist pride and imperialist aims. The 1920s represents another journalistic low point when truth took a backseat to sales. The New York Daily Graphic specialized in doctored photographs it called “composographs.” The National Enquirer continued this tradition with its “coverage” of alien abductions and other nonsense. Even respected papers succumbed to sensationalist strategies. I remember buying a copy of the San Jose Mercury in the 1970s with the banner headline “SOVIET SUB FOUND IN BAY.” It turned out to be a bay in Finland. That was the last time I bought the Mercury, even though I had been a stringer for it in high school.

Today’s fake news, as generated on Facebook by Russian bots and right-wing hacks who make no pretense of journalistic integrity, is more insidious. It’s also the label our tweet-mad president applies to any news item he doesn’t like. These falsehoods are more injurious to democracy than any lie that ever passed the lips of a newsboy.

Most accounts of the struggles over child labor emphasize the stories of children working in factories during the Industrial Revolution. How would this story look different if we centered on the news industry?

I approached newsboys not just as objects of reform, but as complex historical actors who worked, played, swore, gambled, struck, and developed their own occupational subculture. Yet in so doing, I think I shed light on the child labor reform movement as well. Newspaper peddling challenges historians’ tendency to draw clear distinctions between child labor and adult labor, work and play, wages and profit, selling and begging, opportunity and exploitation. News peddlers blur the line between these activities. The fact that their workplace was the street also raises questions about what constitutes endangerment or supervision, not to mention employment. Newsboy labor was also much more romanticized than other forms of child labor due to the influence of novelists like Horatio Alger and artists like J.G. Brown. The newspaper industry participated in this line blurring. Many newspapers sponsored newsboy bands and commissioned newsboy marches and “galops” at a time whena “Breaker-Boy March” or a “Mill Girl Galop” would have been inconceivable.

The other thing that stands out in studying child street laborers, especially in the Progressive Era, is the prominent role played by socialists in this reform movement. Ardent socialists such as Florence Kelley, Scott Nearing, Robert Hunter, and Upton Sinclair provided much of the intellectual energy and documentary evidence that drove the crusade. Sinclair, of course, went on to write a stinging critique of the capitalist press in his book The Brass Check.

But newspapers were not just exploiters of the children they relied on. We have to take into account that the newspaper industry was, arguably, one of the most influential child welfare institutions in the United States. Newspapers were pioneers of corporate welfare and scientific management schemes. They provided newsboys with banquets, excursions, entertainments, and educations in the form of night schools and scholarships. Indeed, one could argue that newspapers exerted a greater influence on American boys than the YMCA, Boy Scouts, or Little League Baseball combined.

Let’s focus on the boy in the newsboy. What myths about masculinity in America have clung to this figure through the years? Were there newsgirls and if so, how were they perceived?

There were always girls and women who sold papers, but the news trade was dominated by boys and it became a kind of school for masculinity. Boys learned not just how to hustle, make change, and predict sales, but also how to smoke, swear, and fight. They learned about sex on the job, dealing with the sexual advances of co-workers, customers, and bosses. The film director Frank Capra routinely fended off drunk pedophiles while working nights in Los Angeles. Girls in the news trade encountered sexual propositions and assaults as well. They were often blamed for their own troubles. “A girl who starts out selling papers ends up selling herself,” said a police chief in Buffalo, New York. Their labor was sexualized in prose and pictures, so they were the first targets of reformers, who pressured lawmakers and publishers to remove girls from the streets.

Your book traces a history which runs for more than a century, despite some significant shifts in the news industry over that period. Why did this figure persist for so long and what led to its demise?

Despite the tremendous growth of newspapers throughout the 19th and most of the 20th century, in terms of number, circulation, capitalization, and employees, their proprietors faced the basic journalistic challenge of getting a highly perishable product to market. The cheap labor of children remained integral to this process for several reasons. First, children were abundant; the steady influx of poor immigrant families up to 1924, especially in cities, ensured an ample labor supply. Second, children proved adaptable to new modes of distribution and new sites of retail exchange, such as railroads, streetcars, bicycles, subways, automobiles, and even airplanes. Finally, the emotional appeal of needy children increased their effectiveness as hawkers and carriers, transforming each purchase into an act of charity, especially when accompanied by a tip, which in many cases made up half their earnings.

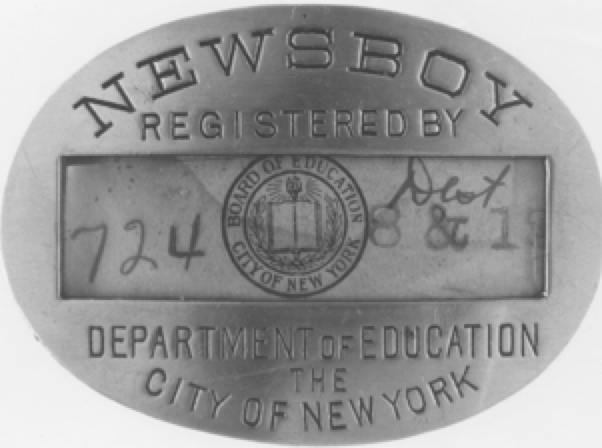

The newspaper industry remained largely impervious to child labor reforms, even during the Progressive Era when the removal of youngsters from mines, mills, and factories often sent them into the less regulated street trades. Despite the tireless efforts of the National Child Labor Committee and its photographer Lewis Hine, the public never really saw newsboys and newsgirls as exploited victims. NCLC investigator Edward Clopper called this misperception the “illusion of the near.” They were too close to us, he said. Conditions changed during the Great Depression. jobs were so scarce that adults now flocked into the trade. But children were still expected to “pitch in” and “help out,” or else make themselves scarce at suppertime.

Only after World War II did the corner newsboys became less ubiquitous due to the spread of newsstands and vending machines and mandatory school attendance. Suburbanization and Schwinns enlarged the fleet of after-school route carriers in the 1950s, ‘60s and '70s. Many of my friends had paper routes then. They never earned much but they got their pictures in the paper once in a while. Adults deliverers with cars were always more reliable and became increasingly preferable after a rash of newsboy kidnappings and murders in the 1980s and '90s. Declining birthrates, increased youth hiring by fast-food chains, and the siphoning off of readers and advertisers by internet companies (that bear no distribution costs) put the final nail in the coffin of America’s newsboys.

Today, those of us who grew up in the post-war era have a certain nostalgia for kids having their own paper routes. What relationship do you see between newsboys and paper routes? How did the latter become associated with the middle class and its assumed virtues?

The contrasting cultural attributes of route carriers and street hawkers is often exaggerated. Many boys did both jobs in the 19th and early 20th centuries; they delivered (or rented!) papers to regular customers and peddled them on the side to random pedestrians. Yet carriers gradually acquired more positive reputations because they tended to rise early, keep regular hours, and go about their business quietly, while hawkers peddled erratically, often late into the night, and made as much noise as possible. When carriers started to outnumber hawkers in the 1920s and ‘30s, they became the focus of new federal regulations. In response, circulation managers emphasized that the boys’ work was a form of public service and vocational education. They started calling them “newspaperboys” and refused to use the old terms of newsboys or newsies, as these words conjured up images of street arabs and guttersnipes. The industry successfully lobbied Congress to have October 4, 1941 declared the first National Newspaperboy Day. It persuaded the U.S. Postal Service to issue a newspaperboy stamp in 1952. And it established a Newspaperboys’ Hall of Fame in 1960. These tributes were publicized annually in radio broadcasts, newspaper editorials, and galas featuring Abbott and Costello, Red Skelton, and other celebrities. So the virtuous middle-class suburban paperboy of our childhoods is not just a happy memory but the product of a public relations machine working overtime to eclipse the disorderly working-class newsboy. Nostalgia, like newspapers, is a manufactured good.

Vincent DiGirolamo has published essays on a wide array of subjects, including child vagrants, Wobbly strikes, Ashcan artists, and Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York. His work has appeared in Labor History, Journal of Social History, Radical History Review, San Francisco Sunday Examiner-Chronicle, and several anthologies. He also co-produced Monterey’s Boat People (1984), an award-winning PBS documentary on Vietnamese refugee fishermen, and published the middle-grade novel Whispers Under the Wharf (1990). His contributions to the digital humanities for CUNY’s American Social History Project comprise essays, podcasts, and teaching modules on the Sand Creek massacre, Jacob Riis, Ellis Island, and the 1934 West Coast maritime strike. DiGirolamo has held research and writing fellowships at the Princeton University Center for Human Values, Woodrow Wilson Society of Fellows, American Antiquarian Society, Bentley Historical Library at University of Michigan, and the National Humanities Center in North Carolina. Crying the News also received support from the NEH, PSC-CUNY, and the Eugene M. Lang Foundation, as well as a 2015 Leonard Hastings Schoff Trust Publications Award from the Columbia University Seminar on the City, a 2017 Furthermore Grant from the J. M. Kaplan Fund, and a 2018 Book Completion Award from the CUNY Office of Research.