Horror, Adventure and Adaptation: Locke & Key from Comics to Netflix (1 of 3)

/We’re massive fans of Joe Hill and Gabriel Rodriguez’s Locke and Key comic book series here at Confessions of an Aca-Fan, and after a troubled history, we finally got the Netflix adaptation in February 2020 in the days before the world changed irrevocably. This week, we have two of the very best comics scholars, Dr Julia Round and Professor Terrence Wandtke, digging deep into the adaptation and the comic series to share their thoughts. Be warned: there are spoilers within.

Horror, Adventure and Adaptation: Locke and Key From Comics to Netflix (1 of 3)

Julia Round & Terrence Wandtke

JR

Over the past decade television seems to have caught up with the comic book zeitgeist and we’ve seen shows as diverse as The Walking Dead (AMC, 2010), Richie Rich (Netflix, 2015) and Lucifer (Fox, 2016) – all adapted from comic books. The pace quickened once Daredevil kickstarted the Marvel Netflix Universe (2015) and today it might seem that subscription television channels have slowly but surely become homes for ever-increasing numbers of comics adaptations. If you’re reading this blog then you’re probably already well aware and have your own opinions on many of the choices that have been made when bringing comic book properties to the small screen. But whether you’re a fidelity purist or in support of any changes that might make comics more accessible to a wider television audience, Netflix’s most recent offering, Locke & Key, raises many questions about the storytelling capabilities of these different media and platforms, the success of horror on the small screen, and the demands of adapting new mythologies and storyworlds.

Locke & Key has a particularly troubled history when it comes to adaptation – two pilots were previously made (for Fox, 2010 and Hulu, 2018) but neither got picked up. So when Netflix’s first season finally premiered on 7 February 2020 I already had pretty mixed feelings of excitement, anticipation, and nervousness. Joe Hill and Gabriel Rodriguez’s comic-book miniseries (IDW, 2008-2013) ran for 37 issues plus a handful of additional one-shots (with some new ones now planned for this year!) I discovered the comic shortly after it had finished thanks to my partner (a non-comics-reader) and I loved it – for me it was a genuinely original piece of comic-book horror that read well, looked fantastic, and had enough twists and originality to delight most fans of the genre, so I had quite a lot invested in the television adaptation. Having now watched it, I don’t feel entirely let down, but Netflix definitely failed to capture some of the things I loved best about the books and in particular there were shifts in tone and aesthetic that didn’t always work for me. Terry, what were your initial thoughts on the comic and the Netflix series?

TW

I’ve been struggling with my objectivity on this because I appreciate the Locke & Key comic books so much. While far from perfect, there are things to love in the comic book series ranging from a keen sense of horror to its genre-bending, from an intricately planned visual narrative to it structural and artistic experimentation. And ultimately, the comic series builds a rich mythology that made it not only effective as a serial narrative but also deeply pleasurable as a narrative background for its stand-alone issues: self-conscious and playful comic book meta-narratives. After now having some distance from my initial viewing of the Netflix series, I can state with a fair amount of certainty that my unfavorable opinion of the television show is not unreasonable. While comic book meta-narratives would never translate well, the rich mythology certainly would. Overall, the story was rushed and despite a few good moments, it seemed to serve the limited patience associated with the audience of lesser CW network shows.

But first, in regard to the comic books: I know I’m not alone in my appreciation of them, considering the series’ relatively high sales figures and award wins (including the Eisner and the British Fantasy Award). Joe Hill probably provided the impetus for the original sell-out of the first issue, a writer who had some name recognition due to the novel Heart-Shaped Box (but who is known, for better or worse, as Stephen King’s son). With that kind of horror pedigree, the series has to deal with certain expectations. On one hand, it really brings the horror and on the other hand, it avoids expectations (by expanding the narrative and avoiding some genre trappings). The title refers to the Locke family, who move to the Keyhouse mansion, filled with magical keys and located in the town of Lovecraft. The starting point could be considered clichéd or classic depending on its execution: family trauma leading to the terror of a haunted house. However, the comic avoids cliché in several ways with one of the most significant being Rodriguez’s graphic detail and fantastic layouts that place the reader in the center of the murder of Rendell Locke and the unlikely escape of his family. In addition to positioning children (and the reader) in the midst of what seems like genuine jeopardy, the revelation of the incident is paced effectively by Hill; it’s doled out in segments, much like trauma is in the lives of those who experience it (unable to extricate themselves from repeated experiences of loss, sorrow, pain, and guilt). Again, I give credit to Rodriguez who is so good with panel structure that repeats what has come before with clear variation to evoke the crawl of time and/or the return to a tragic memory.

JR

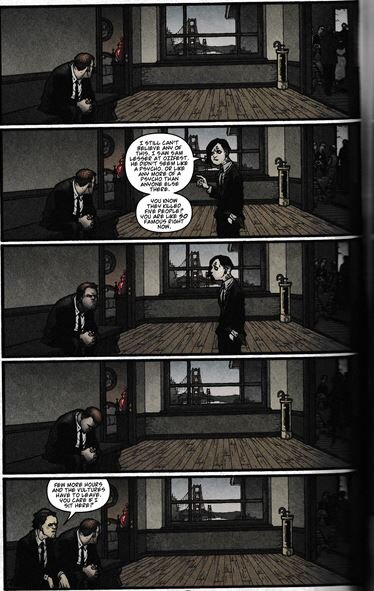

I totally agree that Rodriguez’s art is fantastic at conveying that sense of endless repetition, where characters are either trapped in their own memories or just enduring the banality of their new lives. I did a quick bit of analysis of the comics and (based on a random sample of ten issues) there’s an average of three sequences of repeated panel composition and form (across three panels or more) in each issue. These sequences often go on for pages at a time, so this is a significant feature of this comic. I’d argue that this foregrounds feelings of claustrophobia and entropy – showing locations as static and unchanging spaces within which time passes, often pointlessly (Vol. 2: p29, p113). And as you say, the technique is used particularly in sequences linked with death and sadness. For example at their father’s funeral (Vol. 1) a layout of the same long thin horizontal panels is repeated across two pages as various family members come to (uselessly) comfort Tyler. Later, when Bode demonstrates his use of the Ghost Key to Kinsey, there’s another double page sequence of repeated panels with his corpse-like body in the foreground (Vol. 1). Freud argues that the uncanny not only relates to doubles, doppelgangers and reflections, but also to the involuntary repetition of acts, so I’d definitely read these repeated panel compositions and sequences as creating an uncanny atmosphere.

To be honest this is one of the things I am less keen on in the Netflix adaptation: there doesn’t seem to be much sense of trauma or loss, and the tone is much more ‘Disney adventure’ than PTSD. There are a LOT of happy family flashback scenes with Rendell Locke – but rather than underlining what the family has lost, I found I had trouble really perceiving him as dead and gone due to the amount of screen time he gets! Tone is obviously a tricky thing to identify and comment on, so to be a bit more precise I guess the whole mise en scene of the Netflix show just doesn’t feel creepy or isolated enough to me – it’s more High School Musical than Halloween. The town has been renamed from Lovecraft to Matheson (ha!) and all the shown or named locations seem intended to reinforce a retro, small-town vibe – from the ice cream parlor where Scot works, to the jokes about Bill and Phil’s clam chowders.

TW

In some ways, the title and name of the town in the comic seemed too obvious as well, but my inclination to groan at these contrivances was quickly overcome. The narrative space of the Locke & Key comic exists somewhere between the cute contrivances of post-Code fantasy comics and the genuine terror of EC horror comics at their best (and Hill and Rodriguez add in a self-consciousness one might associate with Alan Moore’s better horror comics). At the start, the most interesting thing about Keyhouse is not its haunting so much as its magic keys: an element that seems to be the stuff of children’s literature but becomes simultaneously full of not only wonder but also dread. One of the later collected volumes uses the term “dark fantasy” to describe what happens and while it is now an overused term, it effectively evokes the experience of the keys. Bode discovers the ghost key and enjoys the freedom of bodiless flight but the reader is consistently treated to his physical form lying corpse-like in front of the door/portal. Rodriguez’s style walks a borderline between realism and caricature that can often be effectively extended to the grotesque at moments like these.

Julia Round’s research examines the intersections of Gothic, comics and children’s literature. Her books include Gothic for Girls: Misty and British Comics (University Press of Mississippi, 2019, and winner of the Broken Frontier Award for Best Book on Comics), Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels: A Critical Approach (McFarland, 2014), and the co-edited collection Real Lives Celebrity Stories (Bloomsbury, 2014). She is a Principal Lecturer at Bournemouth University, co-editor of Studies in Comics journal (Intellect Books) and the book series Encapsulations (University of Nebraska Press), and co-organiser of the annual International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference (IGNCC). She shares her work at www.juliaround.com.

Terrence Wandtke is Professor of Literature and Media Studies at Judson University in Elgin, IL where classes taught include Comic Books and Graphic Novels and Media Theory. He has directed the school’s film and media program, served as the area chair of Comics and Comic Art for the Popular Culture Association Conference, and currently acts as the editor of the Comics Monograph Series for the Rochester Institute of Technology. He is author of The Comics Scare Returns: The Resurgence in Contemporary Horror Comics (RIT), The Dark Night Returns: The Contemporary Resurgence in Crime Comics (RIT), and The Meaning of Superhero Comic Books (McFarland); he is the editor of the collections Robert Kirkman: Conversations (forthcoming UP of Mississippi), Ed Brubaker: Conversations (UP of Mississippi), and The Amazing Transforming Superhero: Essays on the Revision of Characters in Comic Books, Film, and Television (McFarland).