Endings, Beginnings, Transitions: Star Wars in the Disney Era: (Part 1 of 3) by Will Brooker and William Proctor

/Proctor

Since Disney acquired Lucasfilm in 2012, it’s safe to say that there has been a pronounced surge in Star Wars-related franchise activity. Naturally, this shouldn’t come as much of a surprise—Star Wars’ new corporate landlords certainly didn’t purchase Lucasfilm and its various intellectual property holdings only to idly sit on one of the most successful profit machines in history. Of course, this activity is hardly ‘new’ either; there have been Star Wars spin-offs since the franchise’s inception. In fact, the very first Star Wars text was not George Lucas’ (1977) Star Wars (which was given the subtitle Episode IV: A New Hope in 1980), but Alan Dean Foster’s (1976) novelization and the first issue of Marvel’s comic book adaptation, both of which were published before the film’s theatrical release on May 25th 1977.

Yet I can’t help but feel that the marked increase in activity since the Disney acquisition—or more accurately, since the first of Disney’s Star Wars’ transmedia expressions, the novel A New Dawn by John Jackson Miller was released in 2014—has been relentless, especially when compared to the Lucas era. There have been five Star Wars films in four years—The Force Awakens (2015), Rogue One (2016), The Last Jedi (2017), Solo (2018), and The Rise of Skywalker (2019). Compared with another of Disney’s prized assets, the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), this doesn’t seem like a great deal at all. There are usually between two and four MCU films on the annual roster, not to mention the various Netflix series and network TV’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. (now approaching its seventh and final season). That being said, there was a twenty-five-year gap between A New Hope (ANH) and the release of the fifth film in the series, Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2002. Perhaps Star Wars was unique to fans precisely because of this trajectory, and perhaps that uniqueness has now been lost in some way.

Disney CEO Robert Iger has suggested recently that the more frantic pace of Star Wars film releases in the latter half of the 2010s has rapidly led to ‘franchise fatigue,’ a rationale that I don’t totally accept given that the MCU juggernaut shows no sign of slowing down yet. Indeed, Avengers: Endgame (2019) became the most financially successful film of all-time despite being the 22nd film in the franchise. With The Rise of Skywalker, the Star Wars film series comprises eleven films, two of which are not part of the episodic Skywalker Saga, which is over 50% less cinematic content than Marvel Studios has produced since the theatrical release of Iron Man in 2008.

What is interesting is that the Star Wars franchise seems to have had a difficult relationship with television. The first live-action Star Wars television series premiered on the new Disney-plus streaming service in November 2019, barely five weeks ago at the time of this writing. Granted, there has been the infamous (and for some fans, quite embarrassing) Star Wars Holiday Special first broadcast in 1978—apparently set between ANH and Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980)—and three animated TV series, one from the Lucas-era, The Clone Wars (2008-). which is due to return early in 2019; and under the Disney brand, Rebels (2014-2018), and the ongoing Resistance (2018-). Although Lucas planned to produce a live-action TV series in the late-2000s, with the working title Underworld, plans were dropped due to budgetary constraints. It would seem that Disney and writer/ director/ actor Jon Favreau have managed to come up with a way to solve the economic peril that worried Lucas with The Mandalorian. Whether or not we consider The Mandalorian to be live-action Star Wars TV is worth considering, I think. To be sure, it’s released weekly in installments (unlike the Netflix model); it’s a combination of episodic and serial storytelling; but its location on Disney-plus means that the series is neither on broadcast or cable, but a subscription-streaming service, a service that is not yet available outside of the US. It’s not quite TV, but it’s not HBO either!

I assume you’ve been watching The Mandalorian, Will?

Brooker

In your comprehensive survey of Lucas TV texts, I think you’ve omitted a couple -- Droids, the further adventures of Threepio and Artoo, which first aired in 1985, and its sister show Ewoks from the same period. Now officially outside continuity, they also introduced elements that were incorporated into the prequels. There were, confusingly, also two TV animated series about the Clone Wars: Star Wars: Clone Wars (2003-2005), directed and with the distinctive aesthetic of Genndy Tartakovsky, and the longer-running, computer animated Star Wars: The Clone Wars, which debuted in 2008.

I must confess the only Star Wars TV I’ve seen until this year, except a passing glimpse, has been the Holiday Special, which I watched once, thinking it couldn’t be as bad as people said. I cringed and grimaced through a lot of it, and fast-forwarded the rest. It does have the distinction of introducing Boba Fett though, which is interesting: the first and the most recent Star Wars TV shows both feature characters in the same Mandalorian armour -- though I’m not sure if Boba Fett and his father are currently Mandalorians within official continuity.

Fortunately for our discussion I have been watching The Mandalorian regularly. Until the release of The Rise of Skywalker, it seemed to me that the official movies were focusing more on the new generation of heroes, and that they were, in turn, aimed at a new generation of fans; The Last Jedi had made it clear, at least for the moment, that we should ‘let the past die’, and was allowing the main characters from the Original Trilogy to fade out of the narrative, replaced by young people who reminded me a little of my own students. Rey, Poe and Finn are smart, enthusiastic, idealistic and full of energy, but my relationship with them as a viewer was inevitably quite different from my hero-worship of Han Solo when I was seven and he was in his early 30s. So I was happy enough to gradually let go of the ongoing saga, leaving it to others, and I found my own nostalgia trip -- comforting and thrilling at once -- in The Mandalorian, which seemed aimed at veteran fans who want more of the old-school Star Wars. The series takes us back to the period immediately following Return of the Jedi, and affectionately recreates the aesthetic of the Original Trilogy, even revisiting some of its key locations such as Tatooine. As such, it has similarities to Rogue One, which of course takes place immediately prior to A New Hope, but I feel it’s pitched at a slightly more mature audience, and its episodic TV structure means there are also significant differences in its storytelling and in the way it develops character.

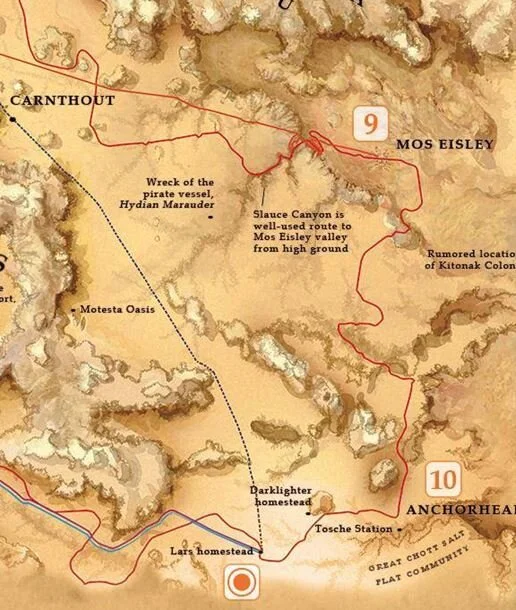

Ironically, J.J. Abrams’ The Rise of Skywalker turned its back, to a great extent, on the forward-looking philosophies of Rian Johnson’s The Last Jedi, and pays extensive homage to the Original Trilogy through its revival of characters who were thought dead, its return to Endor and the second Death Star -- with a bonus glimpse of Bespin -- and its flashback to Leia’s Jedi training, complete with CGI de-aged actors. So we’re in a unique, unprecedented situation where the Skywalker saga has ended in cinemas after 42 years, and the first Star Wars TV show has just begun -- and despite the differences between them, there are also remarkable overlaps between the two. Leia’s training sequence must take place relatively soon after the end of Return of the Jedi, which is exactly when The Mandalorian is set; The Mandalorian revisits the Mos Eisley cantina, and The Rise of Skywalker concludes at the Lars homestead, which is a landspeeder drive away.

Surprisingly, then, the two official, dominant, top-level canon Star Wars primary texts at the end of the 2010s are retrospective and nostalgic in their approach, rather than launching into new timezones and territories, or even moving the saga gently away from the trilogy that ended decades ago, in 1983. We might ask whether this is a symptom of a broader 1980s nostalgia, evident in Stranger Things, IT, Black Mirror’s ‘Bandersnatch’ episode, Ready Player One, the Transformers movie Bumblebee, the forthcoming Wonder Woman 84, and even Joker.

We can return to The Rise of Skywalker later, but what’s your view of The Mandalorian? Has Lucasfilm/Disney succeeded with this bold experiment into live-action TV?

Proctor

First of all, I did miss Droids and Ewoks off my list of Star Wars TV! I also forgot the live-action films Caravan of Courage: An Ewok Adventure (1984) and Ewoks: Battle for Endor (1985), both of which were made-for-TV (although the former also received a limited theatrical run). In fan circles, I’d no doubt take a well-deserved drubbing for that (my symbolic, subcultural bank now emptied of funds, my fannish identity in ruins).

Badinage aside, I understand what you mean about Disney’s Star Wars films, especially the Sequel Trilogy. As a first-generation Star Wars fan—first generation not being ‘better’ or superior to later fan generations—my force-platonic ideal is so attached to the Original Trilogy, aesthetically, generically and narratively, that unless new Star Wars content taps into that ideal in some way, unless it ‘feels’ like Star Wars to me, then I’m always going to have a tough time enjoying or embracing it. I recall Henry Jenkins saying that the prequels symbolizing ‘an open wound’ in the Star Wars community, but that’s not strictly accurate, I’d argue. Fans who grew up with the prequels as their Star Wars trilogy are more likely to embrace them as ‘the best.’ In research that Richard McCulloch and I conducted for the World Star Wars project, there are many respondents who cite one of the prequels as the ‘best’ Star Wars film, and mapping their ages seems to bear out this notion of generations. I guess the Disney sequel trilogy will work the same for this (third?) generation, too. But we’ll come onto that later.

As with HBO’s Watchmen, I wasn’t concerned about engaging with The Mandalorian; not with indignation or hostility, but mainly indifference. I initially thought that drawing from the Star Wars image-bank with a character that closely resembled fan-favourite Boba Fett was disingenuous, but once I came across positive discourses on social media, not least of all the fleet of memes snapshotting ‘the Child,’ or as christened online, ‘Baby Yoda,’ who can’t literally be a fledgling Yoda as the character died in Return of the Jedi—unless he has been resurrected in the Zen Buddhist tradition—I decided to try it out, if only to participate in the cultural conversation.

Like your assessment, I enjoyed the series much for the same reasons as I think Rogue One is the best of the Disney Star Wars films. That The Mandalorian is temporally-situated in the aftermath of Return of the Jedi means that the series looks and ‘feels’ like the Original Trilogy aesthetic, perhaps directly and consciously servicing first generation fans, like you and me.

Although the first episode, ‘The Child,’ had its moments, some of which are quite funny, especially Takika Waititi’s IG-11, I wasn’t overly enamored. But by the third episode, I found myself looking forward to new episodes every week. Unlike the streaming model of releasing complete series in one go, as with the majority of Netflix and Amazon Prime’s original programming, The Mandalorian’s weekly release pattern felt strange at first, then very welcome. I haven’t thought my response through that much, but as I was watching HBO’s Watchmen during the same period on a weekly basis, it was quite an alien viewing experience, more akin to the way we simply had to watch television prior to the inception and proliferation of streaming platforms; and for me, that led me to reflect on my engagement with contemporary television culture. The weekly release pattern dictated that I slowdown, which made me think about the way in which my own engagement with TV in the streaming-era is often a mad-dash to be up-to-date! Sometimes, I yearn for the days when there wasn’t so much media available, and one didn’t feel that they were drowning in an ocean of so much content. My stack of films and TV series ‘to watch,’ as well as the armada of books and comics I want to read, has become more like a chore than ever before. I’m only speaking about my own experiences, of course.

How did you find the weekly viewing experience? What is it in particular that you believe is experimental about The Mandalorian?

Brooker

By ‘experiment’ I simply meant commercially, as the franchise’s first live-action TV show since 1978. The Mandalorian is very far from experimental, except perhaps in its inclusion of both Werner Herzog and Taika Waititi in the opening episode. In fact, its structure reminds me of The Littlest Hobo (1963-1965), the later seasons of Lassie (1964-1973) and contemporary shows like The Fugitive (1963-1967), in that every episode up until the finale is a self-contained adventure that progresses the overall narrative very slowly, but tends to return roughly to the status quo by the end: a nomadic character on the run meets new people, faces new challenges and then keeps moving, never able to settle. This structure is not confined to the 1960s by any means; The Littlest Hobo was revived from 1979-1985 and as I remember, 1980s classics like Knight Rider, Airwolf, Street Hawk and even The A-Team follow the same pattern. In the 90s, The X-Files also had its self-contained ‘monster of the week’ episodes that make no attempt to progress the overall story-arc. But I’d suggest that this classic approach to TV storytelling fell out of fashion with the ambitious box set dramas of the 2000s, and that in this sense, The Mandalorian feels comfortingly old-fashioned. The last show I remember like this was Firefly, which was also the last show I binge-watched: I almost invariably watch TV on a traditional week-by-week basis, even when all the episodes are available.

Of course, The Mandalorian is also nostalgic in its approach to Star Wars, and I’ve been delighted to see the return of locations, props, vehicles, droids and alien races we haven’t encountered in live-action canon since The Empire Strikes Back or earlier: Ugnaughts for instance, the workers from Lando’s Bespin facility; IG-11, the same model as bounty hunter IG-88; a gatekeeper droid of the type we last saw outside Jabba’s palace; the Imperial Biker Scouts first introduced on Endor, and even a Troop Transporter, a 1979 Kenner toy that has only previously featured in Marvel comics and animated series. These affectionate reprises of the Original Trilogy’s aesthetic offer me, as a fan since 1977, what I can best describe as the pleasure both of recognition and of being recognised, as if the saga is acknowledging me again; there’s a mixture of thrilling novelty and reassuring familiarity to the dynamic. The best single example is when the Mandalorian visited the Mos Eisley cantina, allowing us to see how much it had changed since A New Hope -- droids now running the bar, with Stormtrooper helmets on spikes outside. The scene felt, to me, like my memory of entering Secret Cinema, which replicated Tatooine in stunning detail and allowed visitors to wander around, interacting with key characters: visitors to the Galaxy’s Edge theme park, no doubt, have similar experiences.

The most obvious point of reference for The Mandalorian is the Star Wars Original Trilogy. But it also feels, for me, like watching a live-action TV show of the 2000AD character Strontium Dog, about a wandering bounty hunter in the Clint Eastwood mode, and reminds me further of Firefly, which was for some time the closest we had to a new Han Solo story, with Nathan Fillion clearly, to my mind, modelling his performance on the Empire Strikes Back period Harrison Ford.

Like Firefly and Strontium Dog, The Mandalorian is a space Western; but in drawing on Westerns, it also intersects with the samurai movie -- fittingly, as both Akira Kurosawa and John Ford inspired George Lucas back in 1977. If we were to chart The Mandalorian’s position on a matrix of influences, it would be at the centre of a cultural network including Lone Wolf and Cub, The Searchers, The Seven Samurai and The Magnificent Seven: it refers back to stories that have already borrowed from and shaped each other. Episode 4, ‘Sanctuary’, for instance, reminded me vividly of the Strontium Dog tale ‘Incident on Mayger Minor’, where protagonist Johnny Alpha protects a homestead but rides away at the end, turning down the temptation of settling with a single mother and her child; but that plot is itself ripped directly from the 1953 movie Shane.

Finally, The Mandalorian has an interesting relationship with The Rise of Skywalker. Although they take place decades apart -- with the exception of the movie’s brief flashback -- they overlap in terms of geographical galactic space, as I’ve noted above, with the consequence that Rey’s cinematic return to Tatooine may have had less nostalgic impact for viewers who’d seen Mando visit the cantina a couple of weeks earlier.

But there’s one further small but significant connection. ‘Baby Yoda’, the Child, performed what fans call ‘Force Heal’ in the season’s penultimate episode, just one day before the release of Episode IX, in which Rey’s apparent ability to heal and revive through the Force was a controversial element. So to those who watched the TV episode before the movie, that power would have been demonstrated and established in canon, albeit very recently; to the majority who didn’t, it ran the risk of seeming abruptly introduced, unexplained and a frustrating change to the rules about the extent and limitations of Force abilities.

Proctor

That’s an insightful intertextual tour of the Mandalorian matrix, Will. Interestingly, I read episode four as a remake of The Magnificent Seven, which was of course a Wild West remake of Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. I also thought of 1970s TV series like Kung Fu, starring David Carradine, and The Incredible Hulk, which had professional body-builder Lou Ferrigno as the green giant. Just as Star Wars did in 1977, The Mandalorian pinballs across an array of intertexts, often wearing its many influences and utterances on its sleeve.

Perhaps we should also consider the backlash from feminist quarters. Of course, nowadays it wouldn’t be Star Wars without at least some negative criticism. Anika Sarkeesian, who became a prominent feminist during the #Gamergate flame wars, angered a minor contingent of Star Wars fans for her pointed criticisms of The Mandalorian, and its showrunner Jon Favreau, for the series’ lack of female characters. ‘Most mass media overwhelmingly centers men,’ wrote Sarkeesian, ‘and perpetuates patriarchy. The Mandalorian is no exception…I guess Jon Favreau was like “well if we just make all the vehicles female like the ship and the Blurrg then we’re good right? That’s just the right amount of ‘female'”.

While I don’t necessarily agree with Sarkessian’s points—I admit that I’m often perplexed that counting characters’ screen-time has become an absurdly unnuanced method of deciding if a series if acceptable to feminists or not—I certainly dislike the way that her tweets became yet another source of online dogpiling and harassment. It is true that Sarkessian’s first tweet about the series wasn’t factual—she stated that the first episode had no female speaking characters, which isn’t accurate. This was first countered not by male trolls, but by another female fan, @thatstarwarsgrl77, who tweeted: ‘I’m extremely tired of your blatant sexism. No one cares about your obsession with women. There’s a concept called Quality vs Quantity. Learn it.’ The Mandalorian has clearly not escaped progressive criticisms of the galaxy far, far away (not that it should).

I think you’re right that the series/serial narrative hybrid that television audiences were more accustomed to, especially between the 1970s and ‘90s, has shifted. Robin Nelson has argued that this model, this combination of self-contained episodes and an overarching serial mythos, was innovated by the likes of the Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-77), and in particular, Hill St. Blues (1981-87). Naturally, this ‘flexi-narrative’ approach to TV series is not extinct—many crime series retain that multi-form structure between episodicity and serialization: from Law and Order: Special Victims Unit to NCIS, both of which have associated spin-offs that are part of a shared universe.

(As an aside, it has been claimed that Star Trek is the apotheosis of televisual world-building, with six TV series produced since 1966. Yet compared with Dick Wolf’s ‘Law and Order,’ and ‘Chicago’ franchises, which occupy a shared universe canvas that involves crossovers between multiple series and properties, Star Trek lags behind in quantitative terms by a significant margin.)

In this era of so-called ‘‘complex TV,’ as Jason Mittell has described it, The Mandalorian seems to not only be a kind of nostalgic throw-back in generic terms, hybridized though it is, but is also less complicated in its narrative trajectory (unless taken as a ‘micro-narrative’ that is meant to be experienced as part of the Star Wars ‘macro-structure’). Not that that is necessarily a bad thing, but I also think that’s its greatest weakness (for me, at least). The plot is quite thin and aimless, although I like the world itself for many of the same reasons you do. At times, I found myself drifting off while watching it, less riveted and engrossed than I like to be.

That said, the cinematography is luscious, the scripting is tight, and it definitely manages to ‘feel’ more like Star Wars than anything Disney has produced thus far (except maybe Rogue One). It could be that the series is meant to be a love-letter sent to people like you and I who grew up around the Original Trilogy; and while it’s not ‘perfect,’ if such a thing is possible at any rate, I have enjoyed following the titular character and his sidekick, ‘The Child,’ more and more as the series progresses. I guess I would say I’m happily ambivalent, if I was pressed.

It’s interesting that you raise the episode where ‘The Child’ heals The Mandalorian with the Force as an entry-way to The Rise of Skywalker (TROS), a kind of paratext that prepares audiences for Rey and Kylo Ren’s new Jedi super-power(s). I’m not sure if that was Favreau’s intention, but since viewing TROS, the first Star Wars film to be released in theatres while being paralleled by another live-action iteration, I have been comparing the approaches. TROS is obviously a blockbuster, a special-effects extravaganza, epic-in-scope, and enormously convoluted—the most convoluted narrative in the Skywalker Saga, I’d argue. Comparatively, The Mandalorian is small-scale, less convoluted and complicated, focused mainly on a single character-arc, rather than an expansive dramatis personae that often robs certain characters of their due. We know that the Disney sequel trilogy—The Force Awakens, The Last Jedi, and The Rise of Skywalker — was not planned with any creative governance and coordination in mind. I’m not saying that Lucas had everything planned out beforehand—clearly, he didn’t. I very much doubt that Leia and Luke were twins even by the time The Empire Strikes Back was released, otherwise that kiss between siblings, with a jealous Han Solo looking on, would be in bad taste. There are other examples which I won’t go into here. Given that the Disney-era of Star Wars includes having the Lucasfilm Story Group, an executive committee that manages the rebooted Expanded Universe of comics and novels etc., it’s very odd that J.J Abrams was pitching ideas for TROS on the day that TLJ was released in theatres. That seems like a lack of managerial coordination that has led to the sequel trilogy being quite a mess, in narrative terms. In my mind, I wonder what could have been had Jon Favreau been in charge of the sequels? Don’t get me wrong; Abrams is a fine director, but he’s not a great scripter (or ‘scriptor,’ in the Barthesian sense).

The idea that Disney has produced too many Star Wars feature films in too short a time that I mentioned earlier fails to deal with the fact that the sequel trilogy not only adds nothing new to the Skywalker Saga, or at least nothing that makes sense, but it also actively undermines both the prequel and original trilogy, which Lucas said was about the rise, fall, and redemption of Anakin Skywalker/ Darth Vader. Consequently, I doubt that many fans are unhappy with the promise of more Star Wars content, but rather, that they’re unsatisfied with the quality of storytelling on offer. Indeed, many of the criticisms of Rian Johnson’s TLJ were not racist, sexist, and so forth, but were about plot, story, and character (especially the treatment of Luke Skywalker). Moreover, if Abrams needs to use interview paratexts to confirm that Finn was going to tell Rey that he’s force-sensitive, then the film has certainly failed in storytelling terms. In fact, the entire sequel trilogy does not fulfill basic narrative logic, in many ways.

Will Brooker is Professor of Film and Cultural Studies and Head of the Film and Television Department at Kingston University, London. Professor Brooker’s work primarily studies popular cinema within its cultural context, situating it historically and in relation to surrounding forms such as literature, comic books, video games, television and journalism. In addition to the numerous essays and articles on film and fan culture that he has published, his books include Why Bowie Matters (2019), Forever Stardust: David Bowie across the Universe (2017), Star Wars (2009), Alice’s adventures: Lewis Carroll in popular culture (2004), Using the Force: Creativity, Community and Star Wars Fans (2002), and the edited anthologies The Blade Runner Experience (2004) and The Audience Studies Reader (2003). He is also a leading academic expert on Batman and the author/editor of several books on the topic, including Batman Unmasked (2000) Hunting the Dark Knight (2012), Many More Lives of the Batman (2015).

William Proctor is Principal Lecturer in Film and Transmedia at Bournemouth University. He is co-editor on the books, Global Convergence Cultures: Transmedia Earth (with Matthew Freeman, for Routledge 2018), and Disney’s Star Wars: Forces of Production, Promotion and Reception (with Richard McCulloch, for University of Iowa Press, 2019). William is a leading expert on reboots, and is currently writing a monograph on the topic for Palgrave titled Reboot Culture: Comics, Film, Transmedia. He has published on a wide-range of topics, including Star Wars, Batman, James Bond, Stephen King, and more.