Surviving R. Kelly, Fandom & Collective Memory: 5 Avenues for Discussing Sexual Violence

/Surviving R. Kelly, Fandom & Collective Memory: 5 Avenues for Discussing Sexual Violence

by Caitlin Joy Dobson

For decades nearly anyone with a pulse could relate to R. Kelly’s music. From the nineties to the early 2000s Robert Sylvester Kelly has been the mastermind behind so much of the soulful “baby-makin” music fans of R&B bump at house parties, high school dances, karaoke, driving in the car.

My mind is telling me no

But my body, my body's telling me yes

Baby, I don't want to hurt nobody

But there is something that I must confess to you

Age ain’t nothing but a number

Throwin’ down ain’t nothing but a thing

This thing I have for you, it’ll never

‘Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number’ by Aaliyah (1994)

produced by Barry Hankerson & R. Kelly

Let's go to the mall, baby

I'll pick you up around noon, lady

Don't you worry ‘bout a thing

Cause' I got all the answers, girl

To the questions in your head

And I'm gonna be right there for you, baby

‘Honey Love’ by R. Kelly (1992)

It is high time we hit the pause button and contemplate how much of our enjoyment as fans throughout the years has been served at the expense of young Black girls and girls of color. By the time of this post I imagine most readers in the US and beyond have viewed, read or heard about the 6-part docuseries (plus bonus clips) Surviving R. Kelly, the exclusive CBS interview with Gayle King, and the follow up special with Soledad O’Brien called Surviving R. Kelly: The Impact. Meanwhile, through a 2-part series called Leaving Neverland and an exclusive interview with Oprah featuring personal survivor testimonies of at least 2 men, Michael Jackson’s alleged years of sexual abuse against multiple boys have been brought back into the spotlight.

CBS’ Gayle King: “The R. Kelly Interview”

The conversation surrounding both cases is nothing new. Thanks to years of advocacy and the power of testimony, through the work of dream hampton, Tamara Simmons, Joel Karlsberg, Jesse Daniels, and Brie Miranda Bryant, in January 2019 Surviving R. Kelly aired on Lifetime to 2.1 million viewers. Since airing, radio DJs, Kelly’s record label, former fans, and entire countries are increasingly motivated to #MuteRKelly. Regardless of where people stand in their opinion, from TMZ to social media to op-eds spanning multiple publications and platforms, the volume on the whisper network has officially been turned all the way up with respect to Kelly’s history of abuse, the truth of his survivors, and more broadly, the topic of rape culture.

No matter your current knowledge of or experience with sexual violence, there are numerous aspects of the series working to highlight some of the most important avenues for discussion we need to be having when addressing rape culture. Below I consider 5 important avenues in the context of fandom. By no means is this an exhaustive list. But it is vital to recognize the complexities of how fandom, public memory, and power dynamics influence and perpetuate the issue of sexual abuse, sexual assault, rape, and overall power-based harm. It is in this fashion we must keep the conversation going.

As a scholar and researcher of gender studies and sexual violence, my intent is to help generate discussion, with nuance but also in working to build bridges between intellectuals and multiple publics. As M. Jacqui Alexander states in Pedagogies of Crossing: Mediations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred, “no matter our countries of origin, decolonization is a project for all” (Alexander, 2005, p. 272). By extension this inevitably includes sexual violence as a side effect, as something learned through colonization, the ramifications of which remain relevant today. Because of existing, historical, systemic forms of oppression already in place, we must understand that although power-based harm affects us all, it affects us all differently. We must bear in mind the complexities of power in order to better understand unique experiences. While “rape culture,” concerning the ways in which society normalizes and trivializes sexual violence, deserves a focused intersectional lens, the case of Surviving R. Kelly lends itself to doing just that.

Fandom and the Power of Public Memory: Critical Engagement with Perceptions of the Past, Present, and Future

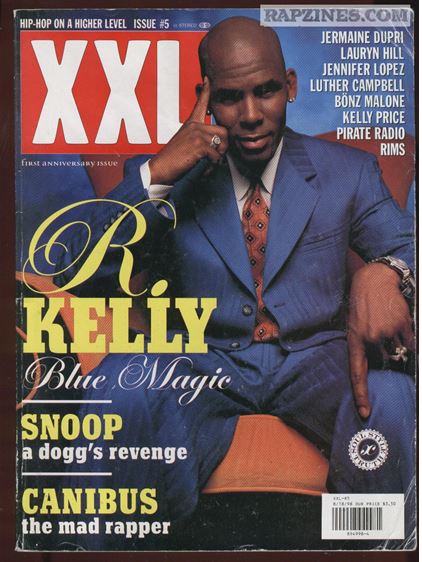

In terms of personal memory, my own fan status might be better attributed in the more general sense to Hip Hop, Rap, and R&B music. As a pre-Internet child of the late 80s and early 90s I read any XXL or Source Magazine I could find. My childhood bedroom floral wallpaper backdropped magazine cutouts of Tupac and Notorious B.I.G., with the words “Can’t we all just get along?” Shamefully, I recall snipping the title of DMX’s single Get At Me Dog and taping it to my puppy calendar. Somewhat understandably, I was as much of an avidly interested “Hip Hop Head” and consumer of a genre as being raised within a predominately white small town in Michigan allowed me to be. Through my portable CD player, stereo, television, and magazines, including this 1998 XXL issue featuring R Kelly on the cover, I kept this music on repeat.

This is not a proclamation of pride in my own personal fan status of Hip Hop, Rap, and R&B but rather an admission of fault. Very much a product of my environment, it is in this space and upbringing white kids like myself openly flirt with consumerism and the privilege of not having to endure much of the hardship and oppression, almost entirely at the hands of white supremacy, that influenced the creation of such art in the first place. It is to say white consumerism, which often self-identifies so personally yet ironically too often remains far removed from actual lived experience, makes white consumers even more complicit in the erasure of and perpetuated violence against Black women.

In terms of public memory, for decades fans of R. Kelly have developed their own mediated memories through the consumption of his music. While these memories serve as a way for us to construct and inform individual identity, they also contribute to the formation of a collective, cultural identity (Van Dijck, 2004), which may not directly align with official histories. They function as an aid to making sense of the world around us, and in relation to one another, in the space where individual and culture meet. These “cultural acts and products of remembering” (Van Dijck, 2004, p. 262) span decades of R&B music as well as R. Kelly’s career.

According to Houdek and Phillips (2017) public memory may be more “informal, diverse, and mutable” as opposed to more “formal, singular, and stable” official histories. In the case of R. Kelly, multiple narratives exist, often in contradiction with one another. For too long, established public memory revering R. Kelly as a musical icon has drown out discussions about the harm he has caused. A much deeper cultural and intersectional analysis is necessary (Crenshaw, 1990; Hancock Alfaro, 2016), in order to understand these complexities, with respect to both Kelly, as well as victims and survivors. In the docuseries Co-Founder Oronike Odeleye talks about the Black community’s reception of the #MuteRKelly movement.

She alludes to a form of cultural polarization, which is to say the way forward is complicated. We cannot discuss R. Kelly as an alleged perpetrator or person who has caused harm to others without discussing the unique experiences with oppression he himself has endured. This is not to say R. Kelly’s race is responsible for the harm he has caused multiple young girls. It is to say R. Kelly’s positionality as a Black man and celebrity in the United States works to inform fandom, in a way that might make it easier or more difficult to hold him responsible for his actions.

I argue we can have both. We can (and must) simultaneously recognize the pain R. Kelly has endured, as both a victim of sexual abuse and Black man growing up in the US, as well as the pain he has caused to others, particularly to young Black girls. The answer may or may not be found in fans turning their backs on R. Kelly, nor in media demonizing him. In the same vein, excusing or refusing to believe a person has caused harm, despite evidence, victim and survivor testimonies, and because you love what their art has meant to you or even an entire community, is also not the answer.

During my adolescence I do not recall being privy to R. Kelly’s alleged transgressions. What I am saying now, as an intersectional feminist scholar focused specifically on power-based sexual violence, is that regardless of our own gendered, racialized, classed experiences with fandom, we cannot let those personal memories disregard the individual and collective pain endured by Kelly’s alleged victims. While I was busy flipping through magazine pages to tear and tape, other young girls’ fan status led them toward coercion and mental abuse by a celebrity perpetrator. Aside from Kelly’s defense attorney, I have yet to encounter anyone capable of sitting through one episode of the docuseries and not believing the pain those women exude is real. In agreement with so much recent coverage this is all to say the same women deserve just as much collective rage as the affluent, white actresses who were victimized by Harvey Weinstein. The onus of making necessary changes in relation to rape culture falls on us, and it takes holding ourselves accountable. In this case this includes our own individual fan status.

Fandom and the Power of Celebrity: Authenticity vs. Accountability in the Face of Adversity

R. Kelly’s stardom is a peak example of what P. David Marshall describes in his book Celebrity and Power: Fame in Contemporary Culture, when authenticity converts into power. For decades R&B fans have been able to personally identify with the authentic, even explicitly sexual nature of R. Kelly’s music, and as Marshall states, “at the center of these debates concerning the authentic nature of the music is the popular music performer” (Marshall, 2014, p. 150). As one of the more enduring transformations in popular music, R. Kelly has been an artist who writes all of his own songs. Coupled with the mass distribution of his music, R. Kelly’s talent effectively infiltrated the hearts and minds of the masses.

Broadly speaking, the effectiveness of Kelly’s ability to display this level of authenticity informs and upholds his celebrity power over a mass of fans, who for years have largely overlooked the fact that he was writing and singing about people he simultaneously victimized.

R. Kelly remained untouchable, cloaked in his ability to produce hit after hit, to generate revenue for the music industry, and to invade dance floors and head phones. His way of surviving was to pass on the pain to undeserving young Black girls and girls of color, thereby desperately attempting to reclaim the power he (to this day) feels he never had. Meanwhile, I am aware of very few R&B fans from the 90’s and 2000’s who did not embrace his music to some extent.

For a child who never learned to read or write, who has opened up in bits and pieces about his own history of sexual abuse at the hand of a family member, music was his outlet. Fast-forward to R. Kelly’s stardom, and it’s as if his musical genius has afforded him the ability to do no wrong. In this respect it becomes all the more necessary to ground discussions of rape and sexual assault in a conversation about power. Generally speaking, we know molestation, sexual abuse, sexual assault, rape, and sexual harassment have so much less to do with sex than with power. Power dynamics existing between a celebrity and their fans can easily lead to an abuse of such power.

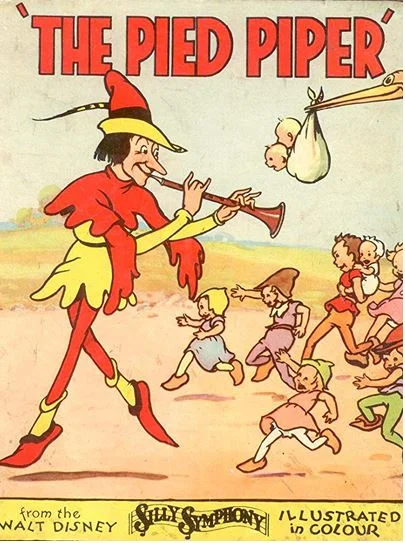

Throughout his career Kelly has referred to himself as the “Pied Piper of R&B,” a phrase which now, in the eyes of former fans and regardless of his own awareness of its historical meaning, only further postulates him as a perpetrator of child abuse.

But that’s the thing about R. Kelly and the power of his celebrity. His self-identified Pied Piper persona is yet another example of the many ways in which R. Kelly hid his alleged offenses in plain sight. Operating as a form of camp, through which a predatorial, misogynistic “badge of identity” (Sontag, 1964) is embraced, it is in this fashion the power of celebrity works to inform public memory. Perceptions of authenticity incite selective memory. Behavior is attributed to style of music. Fans look the other way.

Although memory may not be mutable, it is malleable. Attributing hampton’s documentary, Tarana Burke’s #MeToo movement, and years of relentless dedication to #MuteRKelly, fans are more capable of collectively flipping the script on memories of R. Kelly. Learning the true meaning behind so many of those historically beloved songs helps to demystify. Applause for musical genius can be converted into holding a perpetrator accountable. Peeling back the layers of abuse in the public eye and openly discussing them in such a way that humanizes a person who has caused harm can also serve as a way of dismantling the facade of celebrity power.

Fandom and the Power of Media: Traditional Journalism, Social Media, and Black Twitter

Media can cause a great deal of harm as well as good. As Manuel Castells argues in Communication, Power, and Counter-Power in the Network Society, mass media functions as a social space within which power is strategized, negotiated, and determined [MOU1] (Castells, 2007). It is through this framework we must consider the case of Surviving R. Kelly, through which narrative power is established and to some extent depends on the medium. The most obvious example is found through the docuseries itself, in which the multi-layered power of testimony shines light and counters longstanding dominant narratives. It is particularly interesting to juxtapose (rather than conflate) Surviving R. Kelly with discussions concerning Leaving Neverland, as well as many of Harvey Weinstein’s accusers. In this case, hearing directly from survivors in such an explicit way has had a substantial impact on public opinion, including fans.

The power of media inevitably includes traditional journalism, particularly decades of coverage of R. Kelly by Jim DeRogatis.

For journalists it seems increasingly important to demonstrate responsibility through rhetoric. As a case in point, this calls for reconsidering the use of terms like “sex cult” and “sex slaves” when discussing R. Kelly’s treatment of women (I’m looking at you, Buzzfeed and TMZ). This is not to understate the gravity of R. Kelly’s alleged actions. It is one thing for Jonjelyn and Timothy as parents of Joycelyn Savage to refer to their daughter’s situation as such. It is another for Jim DeRogatis, Buzzfeed, and other mainstream news outlets to sensationalize a story at the expense of victims. It undermines the importance of mental coercion, influencing a victim to stay with their partner at their own “free” will. More often than not, clickbait terms like these do little to advocate for victims, nor are they necessarily effective in demonizing R. Kelly in the public eye. Instead, this type of misrepresentation trivializes the pain victims and survivors will continue to endure for the rest of their lives. And it erases the potential for understanding thus addressing the complexities of sexual violence.

Beyond the scope of multiple op-ed pieces and news articles influencing public perception of the case, social media, the #MuteRKelly campaign, and particularly Black Twitter are spaces where power is negotiated daily. The power, influence, and mere presence of social media is unique from much of the history of allegations against R. Kelly. The immeasurable power of Black Twitter alone is notable, in that voices otherwise stifled by systemic racism in the US speak volumes. Social media exchanges, and often the virality of a particular perspective operate as a reflection of public opinion, and in this case, polarization. Not only do social media discussions, as a ground-up form of citizen journalism, steer some of the power away from traditional news outlets, it provides necessary nuance. It affords a topic like this a much-needed critical lens in real time, often disrupting the status quo thus more accurately reflecting public opinion.

Fandom and the Power of Victim Blaming: The Psychology Behind Attitudes Toward Victims and Survivors

Arguably the most important aspect in need of unpacking and dismantling is the role of victim blaming, through which Chicago Sun Times Journalist Mary Mitchell expresses frustration in her coverage of R. Kelly.

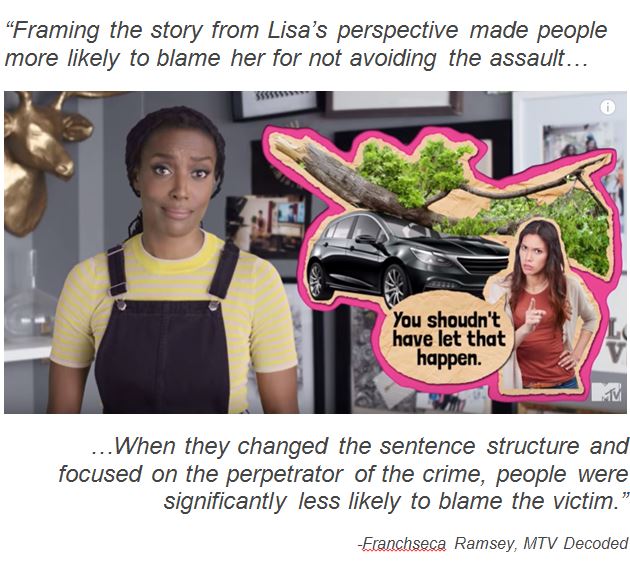

The psychology behind victim blaming runs deep, and it is much more common than we think. Through the following #Decoded #MTV video, Franchesca Ramsey explains the Just World Hypothesis, and why people default to blaming victims in moments of crisis and helplessness.

‘how to stop victim-blaming’ (video)

Focusing on perpetrators of rape and sexual assault can not only serve as an antidote to victim blaming, but it can help us better understand perpetrators, thus more effectively working to prevent future occurrences. While recognizing the psychology behind victim blaming must remain a staple part of conversations about sexual violence, and while misogyny in Hip Hop, Rap, and R&B music is a complex, multi-layered conversation deserving of its own focused attention, both point to a broader discussion of culture and context. Considering the ways in which young Black girls and girls of color who are victims of sexual violence are not considered as important as victims of sexual violence who are white, brings us a step closer to standing up for all victims and survivors. In the same vein we must refrain from suggesting how people can avoid being raped, and instead focus on how people can stop committing sexual violence.

Fandom and the Power of Believing Victims: Intersectionality, #MeToo, and Why Black Girls Matter

Critically contemplate the power dynamics between R. Kelly and young girls who are fans, and it becomes easier to understand how abuses of power can occur. Simultaneously, by way of empathy and placing ourselves in the shoes of victims, to the extent we are able, we might better understand their own feelings of powerlessness. Couple this with the experience of moving through a world where Black girls and girls of color are already systemically, institutionally, and socially shoved into the margins of society, and it becomes easier to understand the power of believing them.

When it comes to attitudes toward victims and survivors, as well as perpetrators, again I suggest it does not have to be one or the other. The answer is not in slut shaming or victim blaming the women, girls, and parents of Azriel, Joycelyn, and Dominique. Nor is the answer in demonizing R. Kelly. Perhaps there are more answers to be found in remaining steadfast in genuine, authentic discussions about culture, about gender norms, about the devastating impact of mental abuse, about the very forms of toxic masculinity people of all genders embrace that perpetuate the cycle of violence.

As numerous women throughout the series mentioned, they have involuntarily carried their trauma with them through life. Regardless of the amount of quality professional help received, quite often survivors must commit themselves to a lifetime of processing their trauma. Based on their survivor testimonies, it seems these women would leave the past in the past, if only they could. It also appears sharing their truth through this docuseries may be an act of freeing themselves, of reclaiming their autonomy and sense of agency. When the majority of instances of rape go unreported, when less than 2-10% of rape reports are false , when legal definitions and policies surrounding sexual violence are perpetually flawed, the least it seems victims and survivors are asking for is to be believed.

Lizzette Martinez, Survivor

In mapping and continuing these important discussions, it is important to acknowledge the connection between R. Kelly fandom and aspects of public memory resulting in: a) society-wide failure to acknowledge the cyclical form of violence continuing to occur- from R. Kelly as a victim of child sexual abuse to an accused serial abuser himself, b) the ability of fans to excuse R. Kelly’s widely-known history of abuse against young Black girls in particular, as he has only recently been formally charged, and c) the audacity of fans to resist believing survivors, to victim blame and slut shame, and turn the other way rather than address the ways in which systemic racism erases Black women who are victims and survivors of sexual violence. When a celebrity, already oppressed in his own right, is implicated, it serves no one to dehumanize anyone. Quite the contrary, the solution is to be found in conversations about accountability, including our own role as fans in perpetuating societal harm. In times like these we must finally recognize fandom, selective public memory, and celebrity status were never an excuse.

—————

References

Alexander, M. J. (2005). Pedagogies of crossing: Meditations on feminism, sexual politics, memory, and the sacred. Duke University Press.

Castells, M. (2007). Communication, power and counter-power in the network society. International journal of communication, 1(1), 29.

Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. L. Rev., 43, 1241.

Hancock, A. M. (2016). Intersectionality: An intellectual history. Oxford University Press.

Houdek, M., & Phillips, K. R. (2017). Public memory.

Marshall, P. D. (2014). Celebrity and power: Fame in contemporary culture. U of Minnesota Press.

Sontag, S. (1964). Notes on camp. Camp: Queer aesthetics and the performing subject: A reader, 53-65.

Van Dijck, J. (2004). Mediated memories: personal cultural memory as object of cultural analysis. Continuum, 18(2), 261-277.

__________

Caitlin Joy Dobson is a Ph.D. student at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Her current research focuses on intersectional feminism, gender and sexuality studies, and power-based sexual violence. She is specifically interested in the issue of multiple perpetrator rape on a global scale, through a comparative, transnational, decolonial, intersectional lens. Through an interdisciplinary lens Caitlin’s work focuses on issues of sexual violence which concern synergistic opportunities between communication, cultural studies, media studies, sociology, forensic psychology, global health, masculinity studies, and international human rights law and policy. Grounded in a wide range of international experience, a background in public diplomacy, a decade of professional experience working in travel, as well as the human rights nonprofit world, currently Caitlin works, volunteers, and conducts ethnographic research throughout multiple organizations, whose layers of expertise address domestic violence and sexual violence. Her current and future research call for a mixed methods approach, from participant observation and depth interviewing to survey, network analysis, and archival research. Her work has been shared through the International Communication Association conference, the International Intersectionality conference, and soon the National Women’s Studies Association conference. She is active in the creation of multiple collaborative endeavors on campus, working to connect the shared interests of peers, colleagues, students, faculty, staff, and community partners. The breadth of Caitlin’s intellectual interests includes critical theories of race and culture, media representation as it relates to rape culture, bridging divides between feminist theory and queer theory, critical whiteness studies as it pertains to popular feminism, white feminism, generational feminist divides, tokenism, cultural appropriation, and most importantly, theories of power. Please feel free to connect with Caitlin at cdobson@usc.edu or on Twitter @caitjoydobson.