Comics, Childhood and Memory—An Autobiography (Part 2 of 3) by Melanie Gibson

/Comics, Childhood and Memory: An Autobiography (Part 2 of 3)

Mel Gibson

I next turn to the most popular of the titles for pre-teens in the late 1950s and on, Bunty, which I experienced entirely as a ‘pass-along reader’. The following images all come from that periodical. I chose to use a single edition here to show different styles of illustration, the use of color and the mixture of new and reprinted material.

Unlike School Friend and Girl, the key difference was that in Bunty the publisher aimed to create comics that they hoped would appeal to working class readers, so developing new markets by further differentiating the audience by class as well as age. Again, as with Girl, the actual audience read across class lines. Familiar tropes and narratives were given new twists in Bunty, most notably, perhaps, in schoolgirl stories. This was the case in ‘The Four Marys’, where one of the ‘Marys’ was a working-class scholarship pupil. This was the narrative most often mentioned by respondents in my 2015 book on memories of comics, and had an impact on several generations of readers. It was reported as about community, unity and friendship, and as enabling girls to overcome obstacles, a narrative of productive and positive inclusion, as is implied by aspects of the story in Figure 4.

However, this approach could be double-edged given that this narrative, like many others, focused on the problems of being a working-class outsider. The stories tended to be concerned with the struggle of such outsiders to deal with the snobbery of, and bullying by, both staff and other pupils. So, on the one hand, one might become one of a very close-knit group of friends, but on the other, one might be victimized because of a perceived difference from the school ‘norm’. As someone who had been severely bullied in school by a teacher before the age of eleven, such stories were far too close to my actual experience to be pleasant reading, again resulting in rejection, especially as I was unconvinced that I would eventually win out as the heroines in the comics did.

These particular genre stories, then, can be interpreted in very different ways. The example below, which appeared in the early 1970s, is a reprint of a much earlier story, as the style of art suggests, along with the uniforms and the dress of the teachers. Here the focus is inter-school sports rivalry and about the consequences of being a ‘show-off’, in this case about a school having superior sports facilities. There is, all the same, a sub-narrative about who is included on the team, with snobbery playing a major part in tensions within the school.

‘The Four Marys’ (Bunty, DC Thomson, 832, Dec. 22 1973, pp. 16-17)

The next two images, also from Bunty, are included to illustrate the domestic and everyday life aspects of the title. The first is the title page featuring the ‘Bunty’ picture story which was an often humorous and affectionate account of the titular Bunty’s life. The anthropomorphized dog in the top corner, whilst a surreal addition, is based on Bunty’s dog, which appears in a more normal form in other stories. Many of these comics had a title which was a girls’ name and the contents and cover were, in effect, a summation of a form of girlhood and of the inferred age and gender suitable interests of the potential reader. As with the Twinkle narrative above there are captions, but no speech balloons, so Figure 5 also shows how British comics for girls maintained a range of modes of address.

Bunty front cover (Bunty, DC Thomson, 832, Dec. 22 1973, p. 1)

The last page of the same edition, featured what was also described in interview (2015) as one of the best remembered aspects of the title across the whole period of the publication of the title, the cut out doll. These pages were often seasonally themed, as is the case here, given that the reader is asked to choose an outfit for a Christmas party. Note also that despite the very different styles of drawing the girls on the front and back cover are both meant to be Bunty, emphasizing the overall identity of the periodical. To actually play with the dolls, in an era before photocopying or scanning were commonplace, meant that the reader had to destroy the ending of the final story, forcing a choice of what was more important to them as individuals. The title was, then, interactive to an extent and this activity serves to point out the agency of the reader.

Bunty Cut out doll (Bunty, DC Thomson, 832, Dec. 22 1973, p. 32)

There were, as mentioned above a number of narratives that featured girls with powers of one kind or another. One of the most popular was Valda (Figure 7) who featured in Mandy from the late 1960s into the 1980s. Many of the narratives focus on adventures, which makes the character increasingly distinct from the domestic and the victim heroine in the comics. Others feature her skills and prowess in a number of sports, including ice skating, tennis and diving. However, she also fights evil and rescues those in difficulty, the latter as shown in Figure 7. She takes her power in part from the crystal depicted around her neck in the main panel, but also has to bathe regularly in the flames of the ‘fire of life’, ensuring the continuation of her skills and youthful appearance, despite being over 200 years old. As a child, what particularly impressed me about this particular story, in one of the few girls’ annuals that I owned, was the abrupt way in which the narrative was introduced. To simply dismiss the concerns and questions of adult males in favor of following one’s own agenda sounded wonderful. Here, then, is another point of contact between girls’ comics and my preferred superhero comics, in what can be recognized as a non-costumed female hero with powers who is assertive and independent. Here the directive aspects, or the focus on suffering, that appeared in other narratives is absent, offering space for celebration, rather than modification, of the self.

‘Valda’ (Mandy Annual, DC Thomson, 1976, p.2)

What the examples above indicate is that there was generally a quite self-contained world, or model, of girlhood (with various age and class inflections) in each of these titles. This was, on the part of some publishers, purposive in maintaining a space between younger girls and popular culture. Popular culture was seen as potentially corrupting, especially for girls, in the mid twentieth century. That comics could be seen as part of that culture was contained by publishers through incorporating content that could be read by adult gatekeepers such as parents as protecting girls from its worst excesses. Comics were consequently not generally part of the synergy around other forms of popular culture and so became lower profile, increasingly detached from the more consumerist model of girlhood offered in magazines.

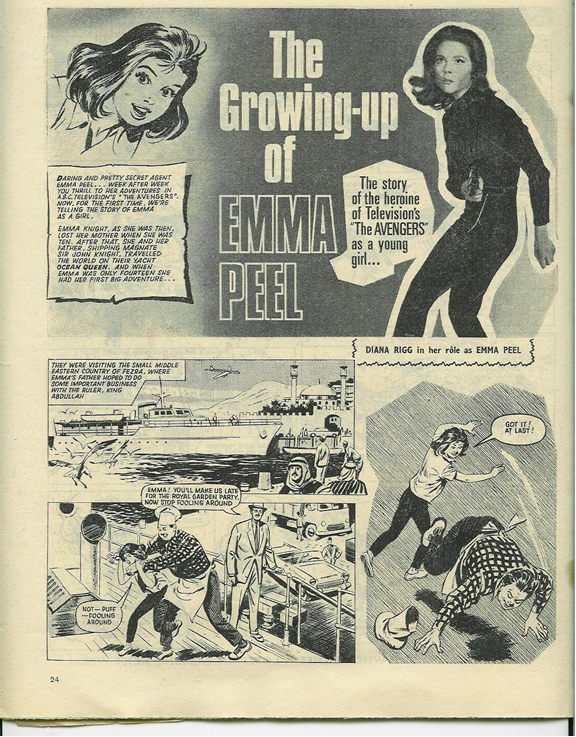

However, this protectionist stance was not consistently followed. The mage below offers an example of a very different approach, given that another way of reading the self-contained worlds of many girls’ comics is not as protection of the girl reader, but as a failure to capitalize on the marketing of other cultural products. The chosen example illustrates the practice of closely shadowing popular television programs from the mid-1960s on. There were comics like Lady Penelope (City, 1966-1969), which in addition to its obvious commitment to Thunderbirds also featured strips on The Monkees and Bewitched (Gifford, 1975, p.95). However, this example is from June, a comic that included strips based on television, but was not dominated by them. ‘The Growing up of Emma Peel’ offers an extension to the series, in what might now be called a prequel. The unfortunate cook that features on the page is later explained to be Emma’s trainer in a number of forms of combat and his role is rather like that of Alfred in Batman. The dialogue serves to suggest that Emma’s father does not take her seriously, but her exclamation ‘Got it! At last!’ is used to show the reader that, far from being a dilettante, she is determined and committed. Here too there is an underlying positioning of the girl as to be shaped, in this case indicating the need for self-discipline in achieving aims. The adult Emma is shown in the photograph that leads into the story, and the assumption is that the reader will be aware of the series, but the emphasis is on what is needed to achieve both her glamorousness and her capacity for action.

‘The Growing up of Emma Peel’ (June, Fleetway, Jan. 29 1966, p. 24)

Dr Mel Gibson is an Associate Professor at Northumbria University, UK, specializing in teaching and research relating to comics, graphic novels, picturebooks and fiction for children. She has published widely in these areas, including the monograph (2015) Remembered Reading, on British women's memories of their girlhood comics reading. Her most recent work focuses on girlhoods, agency and contemporary comics. Mel has also run training and promotional events about comics, manga and graphic novels for schools and other organizations since 1993 when she contributed to Graphic Account, a publication that focused on developing graphic novels collections for 16-25 year olds, which was published by the Youth Libraries Group in the UK.

The ‘Remembering UK Comics’ series is edited by Dr William Proctor and Dr Julia Round.