Cult Conversations: Interview with Steve Jones (Part II)

/Can you expand on your point that “we also don’t really need political reality represented via horror right now”? Don’t you think that cinema could, and should, critique the current political landscape?

I was being facetious, implying that our current political reality is horrific enough without the need to exaggerate it via horror’s lens. Filmmakers can certainly critique the current political landscape (and here I'm talking about capital-P Politics). That said, there has to be a purpose. Typically, horror filmmakers don’t make films as forms of activism, but instead opt for critique, satire, and consciousness-raising from a broadly leftist political perspective. Those forms are much more pertinent at moments when there is a lack of such discourse. Horror can articulate and illuminate a minority viewpoint, for instance, or make strange that which has become commonplace. Making an anti-Brexit movie in the current climate seems ineffective insofar as that view is the leftist status quo. To illustrate – and my thanks to Victoria McCollum for pointing this out on Twitter – Nick Pinkerton’s review for The First Purge in (Sight and Sound) puts it this way: "The First Purge has things to say about contemporary America, but who doesn't? And who cares, if it only has another pathetic yowl to add to the din?".

What ‘hidden gems’ have you discovered on DTV or streaming services? And what indie horror films would you recommend to readers?

I was really impressed with Malady (2015), Circle (2015), and Coherence (2013), all of which are underpinned by smart ideas and make great use of limited locations. Eat (2014) and Excision (2012) have been criminally overlooked. Shudder released Dearest Sister (2016), which I'd been dying to see (I contributed to its Indiegogo campaign). This isn’t horror, but I buy anything that Third Window Films release. They have a fantastic eye for quirky drama.

One difficulty I have here is that I wouldn’t necessarily recommend some films. I found both Landmine Goes Click (2015) and Be My Cat: A Film for Anne (2015) effective, but I suspect that many readers would find them unappealing or even objectionable because they are (intentionally) uncomfortable to sit through. The same goes for Unearthed Films’ releases. They are highly reliable in their niche and I regularly buy from them, but I wouldn’t generally recommend a film like Flowers (2015) per se.

You mention the term ‘micro-budget,’ a concept that has been gaining traction in recent years, much of which is attributed to the phenomenal success of Blumhouse Production. Is there a difference between low-budget and micro-budget, do you think? Or is micro-budget a signifier of a different economic model? Press discourse seems to emphasize that Blumhouse are doing something ‘new,’ with producers, such as Platinum Dune’s Brad Fuller, making claims about Blum’s ‘five-million dollar model’ as relatively recent. With horror generally being ‘cheap’ to make, as you suggested earlier, what marks out micro-budget horror from other low-budget examples from the genre. After all, eighties ‘slasher’ franchises, such as Halloween, A Nightmare on Elm Street, and Friday the 13th, were all low-budget films in comparison to the blockbuster tradition.

As you suggest, these distinctions are not well established and the lines are blurry. To give ballpark figures (and I'm pulling these out of the air), I'd consider anything between say $3-$10m low budget, anything under about $3m to be ultra-low budget, and anything $500k and below to be microbudget. Those are just rough brackets, but it gives you a sense of the kinds of films I'm referring to. The term ‘micro-budget’ has gained traction as so many more features can be made for so little thanks to affordable digital cameras and pretty decent low-cost editing software. Many of micro-budget horror features are funded by crowdfunding campaigns, typically made on budgets of $10k-$25k. Some are even lower than that: Amateur Porn Star Killer was reputedly made for $45 according to its director. Films like that tend to be passion projects (otherwise they wouldn’t get made), and I find that dedication infectious.

It is interesting that you equate micro-budget with $500K and below. The current popularity of Blumhouse films, and discourses surrounding Jason Blum’s economic model, unequivocally put the micro-budget finances in the £5million range. As you said, these commercial distinctions are blurry. Perhaps micro-budget is in a higher range than low budget, more akin to mid-budget? Or do you see the term as more of a discursive marketing instrument than a legitimate descriptor? How do you think scholars might address these economic concepts in more cohesive ways?

The issue may stem from a broader reluctance to engage with very cheaply made films. The press certainly might consider $5m a miniscule budget, but press critics almost exclusively focus on theatrical releases. A film made for $25k might screen at specialist festivals, but it is unlikely to make it into the multiplex. Academia fosters similar biases towards larger-scale releases. It is challenging writing about films with such small budgets because, without the broader marketing that larger budgets allow, such films remain relatively obscure. Demonstrating the significance of such films to peer reviewers is hard when they haven’t previously heard of a film or think that discussion of such films would not appeal to a broader readership. Consequently, it is difficult to publish on such films, and so they remain undocumented in the academy, and so the discourse regarding budgets remains unchallenged, and so it goes.

It seems vitally important to me to distinguish between a film made for less than $500k and a film made for $5m. Lumping them together as “microbudget” does disservice to how different the production, marketing and distribution processes are. One term I haven’t yet mentioned is “no budget” film. I dislike the term because I’m pedantic (i.e. no budget = $0), so I try to avoid it. I'm sure some would use the term “no budget” to refer to the very minimal budgets I'm taking about.

It would be really useful to have a set of economic standards that filmmakers, academics and critics could refer to so as to clarify the differences. Such stipulations might exist, but I haven’t yet encountered a universally accepted set of economic brackets (I’ve just seen the kinds of “plucked from the air” generalisations I offer here).

What do you think of the state of cult and horror studies in the current moment? Is it led mostly by white men, or is there a general mixture of racial and gender diversity? Which scholars do you think readers should seek out?

The area is certainly growing. Doctoral students and early career researchers are helping to develop the field in interesting directions. That said, I spend most of my time reading outside of cult and horror studies by proxy of my gravitation towards ideas as the starting point. As a reasonably young subject area, horror studies still does not have a long history of theoretical approaches to draw on. Much of horror studies is also oriented around specific texts/examples. That seems to be the standard way we work in this area. However, that tendency either limits the author’s ability to make broader points about the ideas, or means the broader applicability is somewhat “hidden”. In comparison, philosophy articles put the ideas up-front, so my attention is drawn towards work in that discipline. I'm reluctant to recommend specific scholars because I'm likely to be nepotistic. My general recommendation is to stray way outside the field. Pick up a book on theoretical fluid mechanics or something and bring those ideas back to the table. I'd much rather read something leftfield than another Deleuzian or Freudian analysis.

So much is being published that I'd find it difficult to make any meaningful estimates about diversity. My feeling is that the field is fairly even in terms of gender, although my view may be skewed by the subject matter I engage with. Purely anecdotally (e.g. by thinking about conference attendance), I'd say that the field isn’t very diverse in racial terms. On that, a shout out to www.graveyardshiftsisters.com who are promoting horror-related scholarship by and about Black women. The site has some fantastic resources and is well worth checking out.

How would you respond to Alice Haylett Bryan’s argument about horror (quoted in The Guardian)?

“Certain subgenres of horror are undoubtedly getting more extreme, but this is the case across culture as a whole, with computer games and television programmes such as The Walking Dead. We are now living in an age where real acts of violence, and indeed death, have been screened on Facebook and YouTube. Could it not be argued that this desensitizes viewers on a more fundamental and concerning level?”

I concur that if we have a particular goal such as collectively aiming to make the world a safer place, then there are better things to direct our attention towards than subsets of horror fiction. There are plenty of real-world harms and injustices that one could prioritise instead.

I disagree with the generalisation that some subgenres of horror are becoming ‘more extreme’. I have written at length about the ways ‘extreme’ is employed so I won’t rehash the argument at length here. To give you an overview of my position (and this is not meant as a direct criticism of Bryan’s statement): ‘extreme’ is typically used as if its meanings are absolute and self-evident. In practice, it is a contingent term, by which I mean that it refers to context-dependent judgements (rather than absolute standards). The adjective ‘extreme’ is commonly employed as if it describes the object being referred to (in this instance, horror films), while offering little (if any) descriptive content. The quotation above carries various sets of values that need unpacking before I could comment with any specificity on Bryan’s position, but the quotation certainly seems to make an implicit correlation between differing kinds of extremities in visual media and “worsening” (possibly cultural decline, certainly some harm to viewers in the form of desensitization). I would guess that Bryan’s comments may have been led by a specific question about desensitisation – it certainly looks that way from the article – so I suspect that these value-based correlations might be coming from the interviewer. My broader concern is that this kind of obscured value-positing is common in the discourse of “extremity”, particularly in the press.

This is an inelegant overview, but I have written about it in Porn Studies journal should any readers want a more detailed (and articulate) rendition of my position.

As you touched on earlier, horror cinema has often been disparaged and delegitimized in film culture. Have there been any shifts towards appreciation and legitimation in recent years? Or is horror cinema still viewed mainly in pejorative terms, in either the academy or in entertainment discourses?

Generally speaking, I’d say that horror is still broadly disparaged. There have been many positive shifts, including a notable increase in scholarship on horror (which has been growing since the late 1980s), and the formation of Horror Studies journal (which signifies that the discipline has generated sufficient critical mass to warrant a dedicated print publication). Nevertheless, horror is still seems to be an easy target for journalists. Get Out’s success at the Academy Awards feels like it was in spite of its alignment with horror (as was the case for Misery or The Silence of the Lambs in the early 90s). By proxy of its status as popular culture, horror doesn’t have the gravitas of drama or art film. That kind of distinction holds firm.

What are you working on for your next project and for the future?

I have several chapters in the pipeline, but my main ongoing project is a monograph on contemporary revenge films, which I’ve been working on for about four years now. My main stumbling block is that revenge has been conceptualised in so many ways that the scholarship (mainly from philosophy, anthropology and psychology) is a mess. To make matters worse, so many films have ‘revenge’ in the title, the tagline, or in the dialogue, and yet there is no hint of revenge (as motive or act) in the film itself. Consequently, I’ve seen well over 800 films for the project, and only around 250 of those are relevant. Frankly, if I'd have known what I was getting myself into, I'd have never started. I need to buckle down on it (and stop myself getting distracted) so that I can finish drafting. I have a pile of ideas for projects beyond that, but at this rate I’ll be retired or dead before I get to any of them.

And finally, what five films would you recommend that you feel represents ‘the best’ that horror/ cult cinema can offer and why?

I need to narrow this down, so I'm going purely for horror here (no-one wants to hear me extolling the virtues of Cool as Ice or Dirty Dancing 2: Havana Nights …again).

A Nightmare on Elm Street (Wes Craven, 1984)

I'll admit that it is flawed, but I love this movie so dearly. It was my gateway into “real” horror when I was a about 9 or 10, and I was instantly hooked. I have seen it at least once a year since then, and it offers something new to me every time I watch it. The film has such a strong core. The narrative is well-paced, punctuating a reasonably slow unravelling of the mystery with startling moments of horror. Some of the effects look a little hokey now, but others – especially those involving the revolving room – are remarkable. The story’s core good-evil dynamic is powerful. Freddy is a well-developed villain even though he is barely present. Nancy is one of my favourite characters in film; smart and courageous, but vulnerable enough to be relatable (i.e. she isn’t superhuman). The premise – the interplay of dreaming/internal/metaphysical and waking/external/physical – is philosophically interesting. The film’s moral dilemmas concerning the parent’s vigilantism and Freddy’s attack on the Elm Street children is richer than is typically acknowledged. Elm Street is my go-to example to illustrate how smart popular gory horror can be.

The Loved Ones (Sean Byrne, 2009)

I had to feature some “torture porn” somewhere on this list, and this film gets nowhere near as much love as it deserves. The Loved Ones is a tight compound or intricately balanced elements that feel like they could explode at any moment. Tonally, it is a strange mixture of romance, teen angst, perversity, dark humour, and hideous violence. I have no idea how Byrne manages to make the film feel like a cohesive whole, but it works. Aesthetically, the gruesome bloodshed is met with beautiful cinematography. The film’s pink/blue colour scheme is luscious, and that complementarity echoes the film’s marriage of differing thematic tones. The Loved Ones’ secret weapon, however, is Robin McLeavy, who plays the film’s antagonist. Her performance is incredible. She walks a tightrope between sweet and rabidly psychotic, but she somehow never fully tips into or abandons either mode. Consequently, it is never wholly clear what Lola is capable of and what she will do next. A great example of contemporary visceral horror.

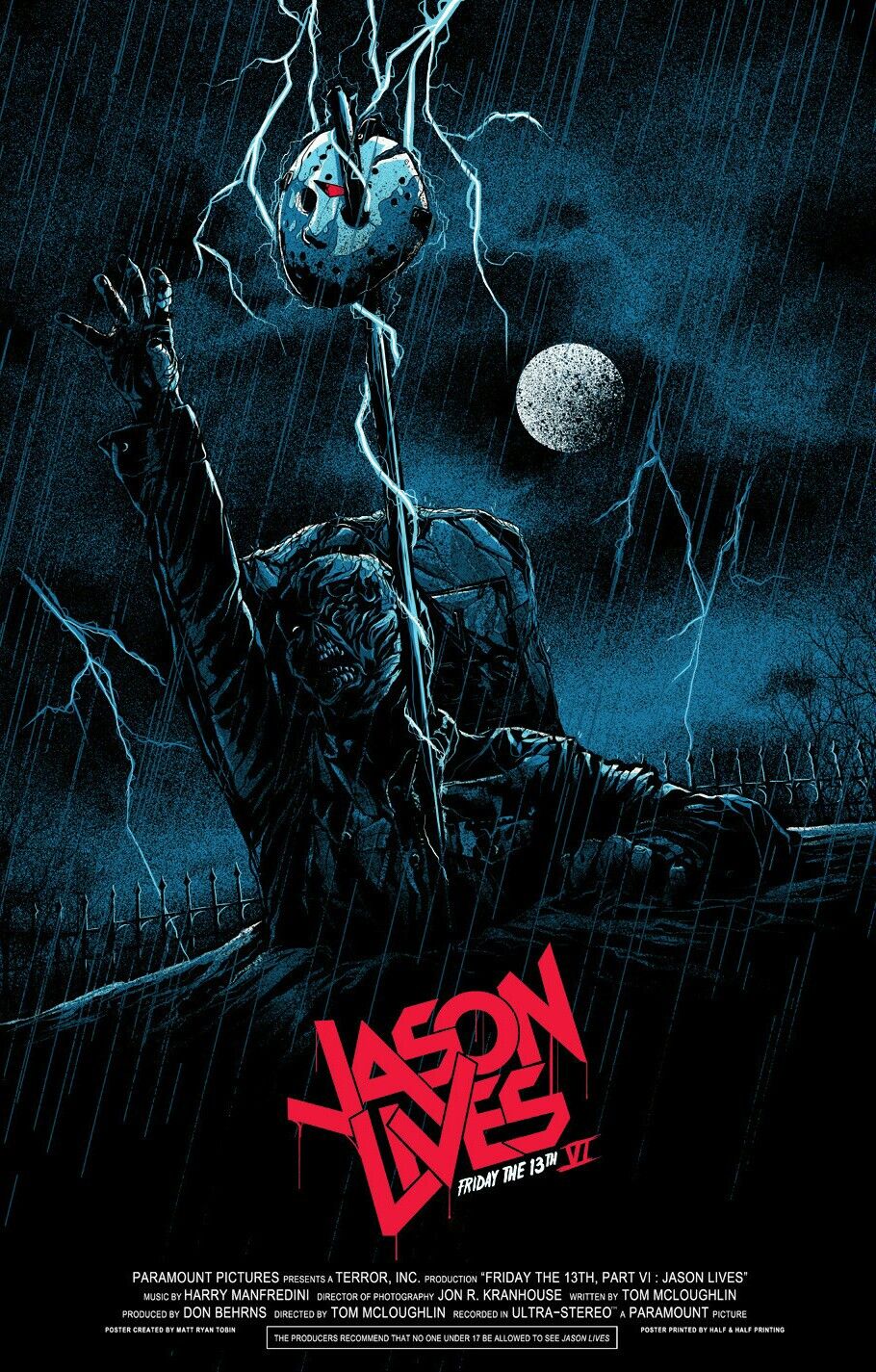

Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives (Tom McLoughlin, 1986)

It may not be serious or thematically rich, but Jason Lives is the definition of entertainment. From the ludicrous opening sequence right though to Alice Cooper’s end credit theme, the film is a riot. Horror and comedy are difficult to balance. It is easy to do when going for over-the-top gross splatter a la Peter Jackson’s Braindead (which is also excellent), but Jason Lives manages to be genuinely funny while also being as scary as any other Friday the 13th film. It is also a great sequel; it builds on the established story, but Mcloughlin also recognises exactly what the series needs after Part IV’s promise of a “Final Chapter” and the stalled attempt to relaunch the series with Part V. The fact that the 80s fashion and music are now so dated only makes it more enjoyable, so it has aged well. More than anything, Jason Lives illustrates that horror can be fun. If I encounter anyone who doesn’t understand that aspect of the genre, I point them here.

August Underground’s Mordum: The Maggot Cut (Fred Vogel, Cristie Whiles, Michael Todd Schneider, Jerami Cruise, and Killjoy, 2003)

Given the themes arising out oi the interview, I feel obliged to represent “extreme” microbudget horror here. August Underground’s Mordum is a well-known example, but it is also indicative of this kind of horror. The content is gratuitously offensive. Much of the run-time is occupied by the antagonists screaming at each other, so it is arduous to sit though even when the antagonists are not killing or abusing their victims. I prefer Michael Todd Schneider’s version of the film as it has more in the way of plot than Vogel’s edit. The love triangle between the antagonists and the group’s decline are fleshed out in greater depth in the Maggot cut compared with the Toetag edit. The plot anchors the film, although it still feels raw and the action seems out of control. That frenzied feeling is facilitated by Whiles’ performance, which is indescribable. Mordum is equal parts found footage horror and unpretentious performance art. At times, it is redolent of Kurt Kren’s Viennese Actionist films. At others, it is closer to atrocity footage. It feels like the gates of hell have opened and someone was there to capture it on film.

Safe (Todd Haynes, 1995)

Horror doesn’t have to be loud and bloody, and it doesn’t have to feature ghosts and monsters in order to be terrifying. This is one of the most common misconceptions I encounter when talking to claim not to like horror movies. There are many horror films that deal in existential dread – Zulawski’s Possession and Bergman’s Persona are prominent examples – but few are as quiet at Safe. Haynes portrait of a character’s decline into self-delusion is wonderfully subtle. The film crawls along, so the atmosphere is muted. This restrained approach allows Julianne Moore to deliver a nuanced turn as Carol, the film’s hypochondriac protagonist. Carol crumbles under the invisible pressures of what we’d now term white middle-class privilege. Nothing happens to Carol, and that oppressive nothingness leads her to self-destruct. The film’s underlying logic is that her comfortable state leads her to feel like she does not matter, even to herself. Carol’s decline is symptomatic of her attempt to find meaning, and Moore ensures that the character remains relatable. Simultaneously, Carol’s hypochondria and a backdrop of pollution/impending environmental disaster provide sceptical distance from her. The film’s tone remains neutral, so the viewer has space to remain critical of Carol’s affluence. Safe illustrates how intelligent and understated horror can be.

Steve Jones is Head of Media in the department of Social Sciences at Northumbria University, England, as well as Adjunct Research Professor in Law and Legal Studies at Carleton University, Ottawa. His research principally focuses on sex, violence, ethics and selfhood within horror and pornography. He is the author of Torture Porn: Popular Horror after Saw (2013) and the co-editor of Zombies and Sexuality. His work has been published in Feminist Media Studies, Sexuality & Culture, Sexualities, and Film-Philosophy. He is also on the editorial board of Porn Studies. For more information, please visit www.drstevejones.co.uk