Cult Conversations: Interview with Robin Means Coleman (Pt.II)

/You also state that the horror genre has at times been “marred by its ‘B-Movie,’ low budget and/ or exploitation reputation.” Are you arguing that it is this reputation that has marred the genre by way of critical disparagement; or that B-Movie, low budget, exploitation cinema is disreputable or lacking in quality?

I want to emphasize the word “reputation” in your question and, earlier, I talked about horror’s B-movie “stereotype.” My point is that I do not want people to think that horror is fixed in some low quality purgatory. Certainly, there are horror films that are dreadful, or are a mixed bag in terms of quality of script and production. More, once the direct-to-video age hit, the format afforded an influx of movies that would never be ready for big screen primetime. I get that. However, the genre does seem to be excommunicated in ways that other genres are completely taken down. Honestly, we live in a world where Adam Sandler’s Billy Madison (1995), Will Ferrell’s Bewitched (2005), and just about anything with Marlon Wayans in it is not tanking the entire comedy genre.

Look, what I believe is that we are retroactively repudiating an entire genre when we did not always believe horror was wholesale objectionable. Are we really prepared to write off Universal Pictures’ horror films—The Mummy (1932), The Phantom of the Opera (1925), Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933)… of course not. So perhaps, just perhaps, a snobbery around horror is more recent. Maybe it was the 1970s splatter and 1980s torture films that we are thinking of when we reject horror. This is a snobbery that is marked by who is making the movie and what kind of stories are being told. That is why knowing a more complete history of the genre is so important.

In your book on Horror Noire you state, “there are a great many horror films that contribute to the conversation of Blackness,” while at the same time, Steven Torriano Berry explains in his foreword that, like Hollywood fare in general terms, Black characters were often the first to die—if they were included at all. Can you explain the way in which the horror genre has historically contributed to “the conversation of Blackness”?

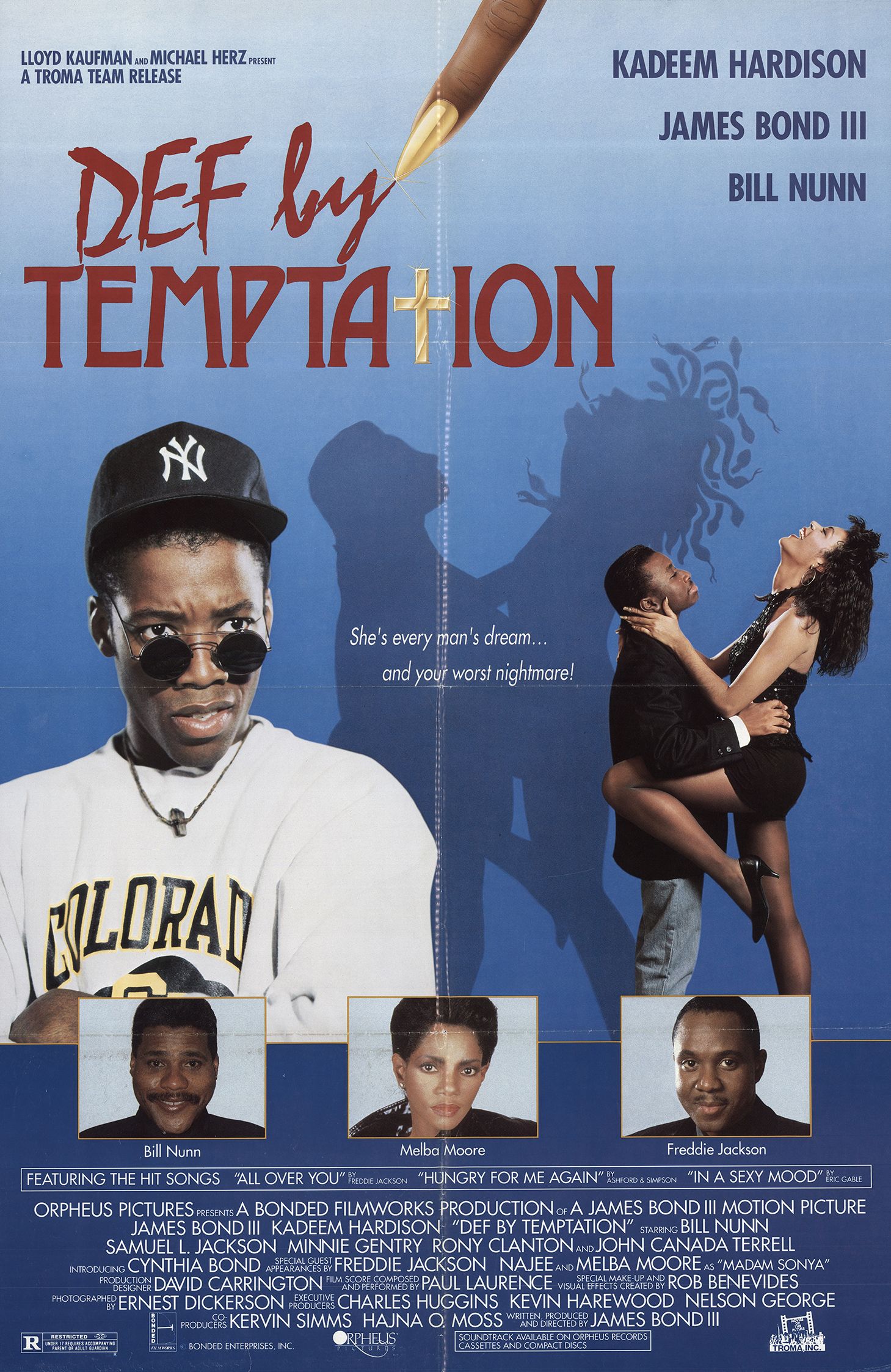

In the book, my particular interest is in horror films that focus on Blackness—Black horror films like Def by Temptation or The Blood of Jesus. And, I talk about horror films that have Black people in it, but whose focus is not especially on Black lives and histories, films like Angel Heart or The Serpent and the Rainbow. I write that these two approaches offer up “an extraordinary opportunity for an examination into how race, racial identities, and race relationships are constructed and depicted.” More, I assert, “certainly horror has always been attentive to social problems in rather provocative ways.” (p. 8). On the whole, I argue that horror is the ideal genre for digging into narratives of American social politics, identity formation, understandings of race, and ideology-making. The book is Du Boisian in that it is informed by his interest in the “strange meaning of being Black” in America.

One way to think about the “strange meaning of being Black” is to understand that Black characters do not always die first in horror movies, and why they don’t. In ‘Blacks in horror films’ (not to be confused with ‘Black horror films’), Black people often serve a particular purpose. They are brought in to reinforce stereotypes of menace, monstrosity, uninhibited violence, and abject deviance. So, if, say, a White anti/hero shows up and vanquishes the Big Black Boogeyman, then what does that say about Blackness and Whiteness? Now, when a real monster hits the scene—an alien, a mutated animal, a zombie—how do we feel about the odds of Whiteness and its superiority? That—setting up Blackness as fearsome, but then destroyed—is truly the strange meaning of being Black in horror films.

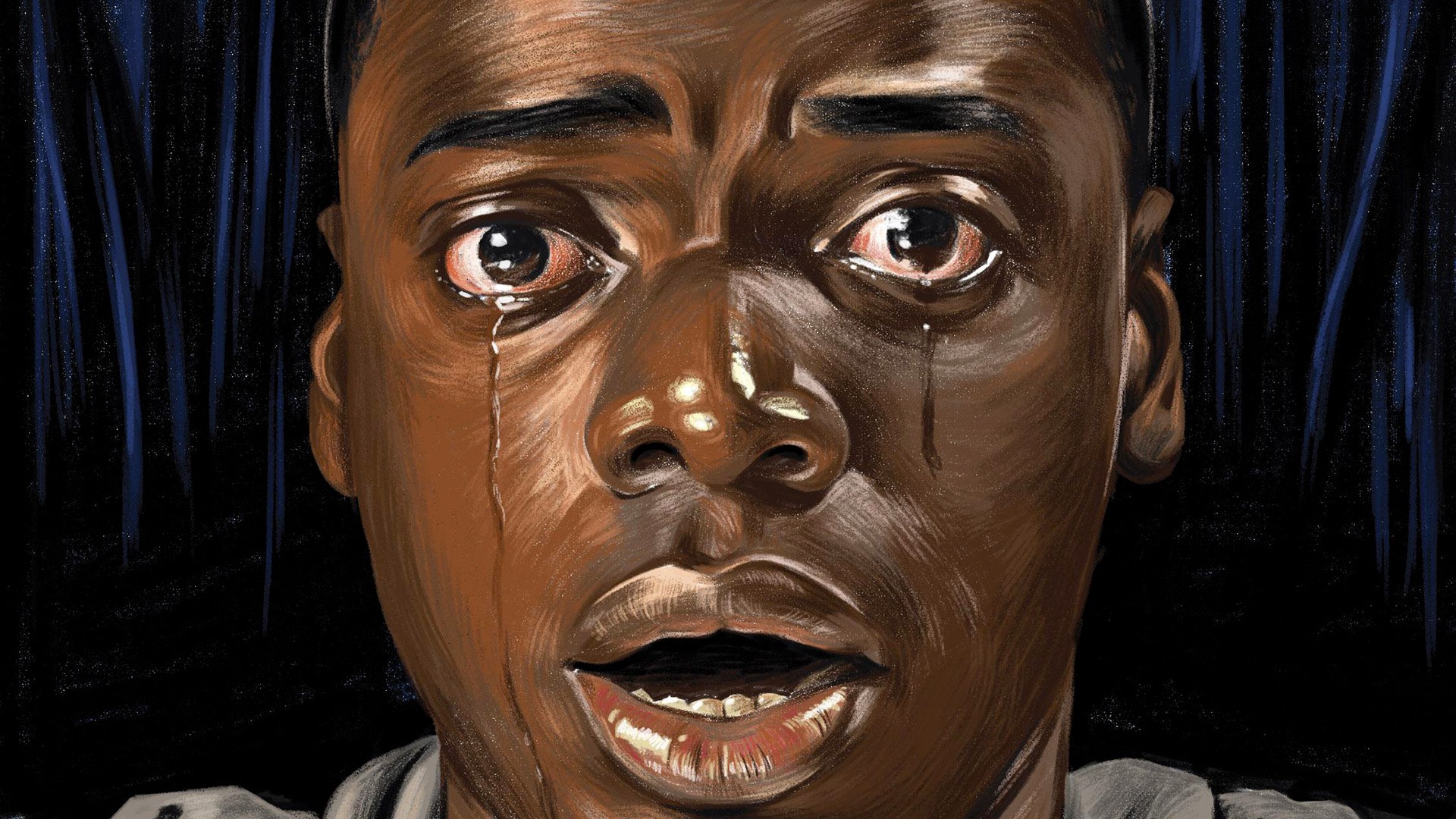

The phenomenal critical and commercial success of Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) seems to represent a significant shift in the politics of Hollywood cinema, a film that operates as “a searing, satirical critique of systemic racism,” as Ricardo Lopez of Variety put it. At the same time, however, “systemic racism” clearly remains an enormous issue in the United States—and elsewhere, of course—with the Black Lives Matter movement being an example of Civil Rights activism in the 21st Century. What do you think about the way in which films, such as Get Out, are critically celebrated and championed by entertainment critics (and audiences), while systemic racism seems to be growing in the real, non-fictional world. What do you think about the relationship between Get Out and the way that the radical right has swiftly grown into a political powerhouse? Do you think that the success of Get Out works ideologically to persuade audiences that systemic racism in the 21st century is not as serious as press discourses would have us believe? Or do you think the film promotes a more progressive, positive message?

Get Out is far from the first horror film to address civil rights, race, and racism. To say that is to turn a blind eye to the 1970s-- an entire decade of Black movie-making that spoke directly to White supremacy, exploitation, classism, and discrimination. To say that is to erase the art of Bill Gunn, Melvin Van Peebles, Ivan Dixon, Ossie Davis, D’Urville Martin, Gordan Parks…

MARIO VAN PEEBLES

But, I understand how people today could think that only Get Out could have something to say about the issues that Black Lives Matters works to intervene on, or that systemic racism seems to be “growing.” These issues are 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st century issues, and Black popular culture has always had something to say about them. When Jordan Peele says that his primary inspiration for Get Out—a film about liberal racism-- is Rosemary’s Baby, I suspect Gordan Parks, Jr. is rolling over in his grave. Parks’ stories of Black genocide weren’t really any more fantastic than that which Get Out is premised on. More, if you know anything about film, you know that these stories about racism have been taken up for years in an attempt to talk back at an ever persistent systemic racism. Get Out stands on the shoulders of Sugar Hill, Three the Hard Way, and JD’s Revenge, whether it wants to admit it or not. But failing to acknowledge this history leaves people to think that Get Out is the most powerful anti-racism voice when, in fact, Black filmmakers have been shouting for more than a century (think: Oscar Micheaux). It is only now that the mainstream is really paying attention our voices.

Don’t get me wrong. Get Out is a brilliant film, and one of my favorites. But, I wonder what the trade-off is to, in some measure, erase Blackness for audiences to attend to Blackness. Take Peele’s movie Us (2019). Peele has been insistent that the movie is not about race. What?! There is no film ever made that is not about race. Rosemary’s Baby is about White people. The Exorcist is about White people. Silence of the Lambs is about White people. Christine is about a White kid and his evil car. Poltergeist is about a White family in their haunted White suburban enclave. Us is about a Black family. It sees Blackness, as revealed by the use of Luniz’s I Got 5 on It as the soundtrack to a lesson on keeping a beat and catching rhythm.

So, Us, like Get Out is likely going to work progressively. Our road there will be a bit more direct with a Peele offering a clearer message about the ideological work his films do.

Writing for the BBC, Nicolas Barber asks if “horror is the most disrespected genre.” Do you agree that this is the case?

I hate to be contrary but, honestly, I am growing weary of this line of inquiry around horror. It comes up so often. Every single popular article starts with this narrative of horror-as-stigma. Every interview I participate in—except when interviewed for horror magazines, interestingly enough--starts here. Questions about ‘how did you become a horror fan?’ really seem to be asking, ‘just how did you get into this screwy genre? What the heck went wrong in your childhood?’ Good grief.

Maybe at this point, horror is a disrespected genre because we have not figured out how to write about it with more regard and in less pedantic ‘define the genre and account for its low budget and exploitation’ ways. Horror does not need mainstream approval, and in some ways benefits without it. Mainstream horror gives us dreck like The Mummy (2017) starring Tom Cruise. Outside of so-called “elevated” horror you get smart, interesting scares like It Follows (2014).

Get Out has been viewed as one of the films that are spearheading a “new Golden Age of Horror,” and that the genre is undergoing a “renaissance,” or “resurgence.” What do you think about these claims? Are we currently experiencing a ‘New Golden Age of Horror’? Is contemporary horror cinema underpinned by a radical shift in recent years?

So, are we in the middle of a horror renaissance? Has Get Out (2017), A Quiet Place (2018), and The Babadook (2014) marked a new golden age? This point from the BBC article what merits our attention, as it is right:

But, Anne Billson, a novelist and critic, summed up those fans’ feelings in a tweet: “Whenever a horror movie makes a splash... there is invariably an article calling it ‘smart’ or ‘elevated’ or ‘art house’ horror. They hate horror SO MUCH they have to frame its hits as something else.”

So sure, these horror films give us a reprieve from the Saw, Hostel, Human Centipede torture porn and grossness of the horror world. They are less gory, smarter, and more palatable. They also have better budgets, celebrity power, and distribution behind them. They succeed because care has been taken to invest in their success. Their mainstream popularity sets them apart. If that is the definition of “renaissance” then yes, we are in one. But, I watched over 3000 horror films to write Horror Noire, films that became cult classics, films that spawned sequel after sequel, and films that captured the pulse of social movements. While, I argue in the book, that the horror films’ foci shifted from decade to decade, they were always here.

They will always be here.

And finally, what are your five favourite horror films, and why?

This is one of my favorite questions!

Get Out (2017)

This is a horror film that is not as fantastical as one might imagine. When Chris meets Rose’s family for the first time, especially her father, Dean, the film perfectly captures the toxicity of White-savior liberalism. What I love most about the film is how it lays bare suburban horrors while revealing the love, beauty, and strong community of the urban.

Dog Soldiers (2002)

So, this is not a Black horror film, but I could watch this movie-turned-cult classic all day, every day. It is about a squad of British soldiers who find themselves in trapped in the highlands of Scotland battling werewolves. This movie is about 100 minutes, and it accomplishes so much with back story, character development, tension, and humor. The cast is amazing: Sean Pertwee (Gotham, 2014-), Kevin McKidd (Trainspotting, 1996), and Darren Morfitt (Doctor Who, 2010). It first premiered on the Sci Fi channel, and I was not impressed. I did not know then that they had edited the life out of the film, stomping it into the ground until it was a dry, unimaginative mess. Later, I saw the original cut on DVD, and I was stunned. Neil Marshall had written and directed a masterpiece, a real imaginative take on the werewolf genre. The movie won a few film awards, and fans have been anxiously waiting for years for a promised follow-up movie (that might never materialize).

Def by Temptation (1990)

If you are studying Black horror, this is a must-see film. Its writer, director, and producer is Black—James Bond III. The all-star cast is Black—Samuel L. Jackson, Kadeem Hardison, Bill Nunn, and Bond. There are cameos by jazz saxophonist Najee and singer/actress Melba Moore. Even Ernest Dickerson the famed (Dexter, Day of the Dead, The Wire, Malcolm X) cinematographer and director is doing his cinematography magic. And, the story is squarely centered on Black life (north versus south) and Black religious (sin and salvation). What I think is really cool is that one of the heros in the film is Bible-toting “Grandma.” These days teen stars are cast in films, and I love that an elderly Black woman is a scene stealer.

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

I came for the glimpses of Pittsburgh and the zombies. I saw a brilliant, gorgeous, commanding, heroic Black man in Ben. Ben completely shattered representations of docility that had been previously assigned to Black men. This movie also shook me. I think Night marked the beginning of the end of my childhood— Ben is such a perfectly complex and human representation who is also an innocent. To have a Black man win, and then have that snatched away through a lynching. My God! It tears at my soul even today.

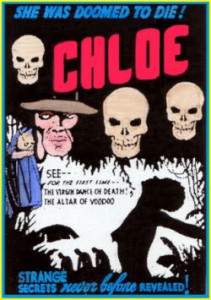

Chloe, Love is Calling You (1934)

I like this film so much that I have written about it. The film focuses on a Black character, Mandy, who gives this racist, White family hell for lynching her husband, Sam. It’s a 1934 film, and we are supposed to read Mandy as irredeemably evil. Mandy, even cross-dresses as Baron Samedi a loa of Haitian Vodou. And still she lives! She’s a totally unexpected Final Girl.

Professor Robin R. Means Coleman is Vice President and Associate Provost for Diversity and a Professor in the Department of Communication at Texas A&M University. A nationally prominent and award-winning professor of communication and African American studies, Prof. Coleman’s scholarship focuses on media studies and the cultural politics of Blackness. She is the author of Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present (2011, Routledge) and African-American Viewers and the Black Situation Comedy: Situating Racial Humor (2000, Routledge). Prof. Coleman is co-author of Intercultural Communication for Everyday Life (2014, Wiley-Blackwell), the editor of Say It Loud! African American Audiences, Media, and Identity (2002, Routledge), and co-editor of Fight the Power! The Spike Lee Reader (2008, Peter Lang). She is also the author of a number of other academic and popular publications. Her research and commentary has been featured in a variety of international and national media outlets. Prof. Coleman’s current research focuses on the NAACP’s participation in media activism.