Cult Conversations: Interview with Julia Round (Part I)

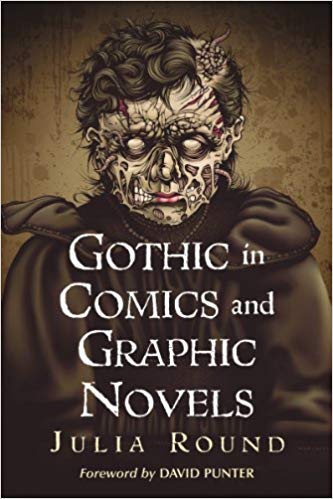

/I have had the honour and pleasure of working alongside Julia Round since I secured my first full-time post at Bournemouth University. Not only have a learned a great deal from Julia over the past four years but I have also been continually impressed by her keen insights and rigorous scholarship—her monograph Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels (2014) is an exceptional work and I highly recommend it. In this interview, Julia and I discuss the Gothic, and the way in which comic books, especially in the UK, have engaged with the tenets and tropes of the phenomenon. I still have a lot to learn from Julia and consider myself a passionate student of her work, going back to when I was an undergraduate and PhD candidate at the University of Sunderland. Throughout our discussion, I was certainly surprised to learn about a relationship between the Gothic and comic books—Julia’s research uncovers the Gothic in “unusual places.” I hope readers find Julia’s insights as erudite and revealing as I have.

—William Proctor

In your monograph, Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels (2014), you begin by saying that: “At first glance it might seem that contemporary comics and the Gothic tradition are completely unconnected.” In what ways, then, do you think that the comic medium has included material infused with Gothic tendencies and characteristics? Was there anything in particular that instigated such a viewpoint?

One of the more obvious examples of Gothic themes in comics is, of course, the American horror comics of the 1940s and 1950s. They were absolutely dominant for a short period of time, circulating over 60 million copies per month. Even non-comics-readers have probably heard of EC’s Tales from the Crypt – and there were many other imitators, all releasing anthology comics full of suspense and gore, alongside the equally shocking crime comics. Like the earliest Gothic texts, these comics went against the grain of social acceptability: they were sensationalist and transgressive. The problem was that they were sold on newsstands and to children, prompting widespread moral panic and a Senate investigation that forced the American industry to commit to a Code of self-censorship in 1954. In many ways this has shaped the comics medium in Britain and America today as it led to the dominance of the superhero genre and the rise of the underground.

But for me, comics’ Gothic tendencies go far beyond horror motifs. There are historical parallels to be drawn, as comics have often been considered sensationalist, lowbrow and subversive – much like Gothic texts. Gothic themes also underpin many genres of comics – not just the obvious examples of horror comics. The superhero is a model of fragmented identity, as the alter ego and super-identity literalise the ‘Other within’ and are only held together through processes of exclusion. Superheroes’ physicality also relies on a monstrous and mutable body. Today the genre has developed away from its action-driven origins, moving towards introspection and confessional narratives. Meanwhile, underground genres such as autobiographix frequently hone in on trauma (Spiegelman’s Maus, Una’s Becoming Unbecoming) or illness (David B’s Epileptic), or explore the place of the individual within society (Sowa and Savoia’s Marzi, Satrapi’s Persepolis) and thus touch upon Gothic themes of isolation and alienation.

The cultures that surround Gothic and comics also share similarities. They both carry a weight of cultural assumptions and stereotypes, for example Goths are seen as depressed, morbid and pretentious, while comics are the domain of geeky fanboys and fangirls. We might consider Goth as an identity performance using surface appearance and fetishized commodities: incorporating both creativity (DIY skill, imagination and daring) and purchase power (access and ability to afford high-end items, materials or particular brands). Comics cosplay performs similar tensions, as it asserts individuality (homemade costumes, the accompanying pose and performance, adaptations and subversions such as re-gendering) whilst still adopting an industry-controlled image. Both Goth and comics subcultures present outwardly as a collaborative group, while remaining split internally in defence of particular titles or types of knowledge. They’re based around images and properties that are strictly licensed, but cosplay and fanfiction thrive, and both groups exist in a fetishized relationship with their own media and artefacts.

Finally, I think comics narratives exploit Gothic in their storytelling structure and formalist qualities, and this is the main subject of my first book. Fans and scholars use Gothic language to talk about comics (‘bleeds’, ‘slabbing’, Charles Hatfield’s ‘tensions’ and Scott McCloud’s concepts of ‘closure’ and ‘blood in the gutters’). Formalist comics critics like Thierry Groensteen, Charles Hatfield, Scott McCloud and Benoît Peeters often draw attention to three shared points: the space of the page, the role of the reader, and the interplay between word and image. My own work synthesises and builds on these critics and uses Gothic critical theory to revalue their ideas. I use three key Gothic concepts (haunting, the crypt, and excess) to analyse the comics page. So I argue that the page is haunted by similarities with previous panels or layouts; that it uses multiple and excessive perspectives as our viewpoint jumps about (in and out of the story, from narration to dialogue – and words may address us directly while visuals immerse us); and that it exploits the hidden and the unseen (in the gutter or ‘crypt’ between panels). I suggest that if we use this holistic approach to evaluate comics, we will find that every page employs one or more of these three tropes to enhance its message, and the way that it is used will give insight into the story.

So for me, comics can be considered Gothic in historical, thematic, cultural, structural and formalist terms, and Gothic characteristics can be found in the most unlikely of places (one of my articles analyses the uncanny perspectives and destabilised narrative used in the Care Bears comics!). As for what started it – well I guess I’m drawn to the contradictions I see in Gothic literature and culture, and to the deconstruction of how stories work. The tensions and paradoxes between surface and depth have always appealed to me.

When did your journey into comics begin? Would you consider yourself a fan first and foremost? Or was it academic study that sparked your interest in the medium?

That’s a hard question to answer – like a lot of scholars who are passionate about their subject, I’m not sure I can separate the two entirely. I read comics as a kid, but not obsessively. I don’t have an encyclopaedic knowledge of DC and Marvel. My comics fandom really started around 1990 when I became a teenager, and predictably enough with DC’s Vertigo titles. Hellblazer, Preacher and of course Sandman were the first ones I remember reading, thanks to my brother. They grabbed my attention and challenged my expectations of what I thought could be done with narrative and storytelling. They were also irreverent, parodic, and self-aware, and I loved that.

My academic study did play a big part in honing my interest in comics though. When I began to encounter critical theory in earnest during my undergraduate degree (BA English Literature, Cardiff University), I became interested in genre theory and semiotics. In particular there were three units I studied that would shape my future research – Children’s Literature (taught by Peter Hunt), Romantic Literature, and Literature of the 1890s. The Vertigo comics told stories that I thought really pushed the boundaries of genre, and exploited the Romantic notion of the author, using structure and semiotics to create reflexive meaning. They enhanced my interest in dark Romanticism, decadent literature and formalist theory, and (after I completed an MA in Creative Writing at Cardiff University, awarded 2001) I decided that comics’ treatment of genre and narratology was what I wanted to explore in my PhD (awarded by Bristol University, 2006). This ended up being a project called ‘From Comic Book to Graphic Novel: Writing, Reading, Semiotics’. My supervisor was landmark Gothic theorist David Punter, which doubtless shaped my thesis as I explored the applicability and use of different genre models in contemporary comics, such as myth, the Fantastic, and Gothic.

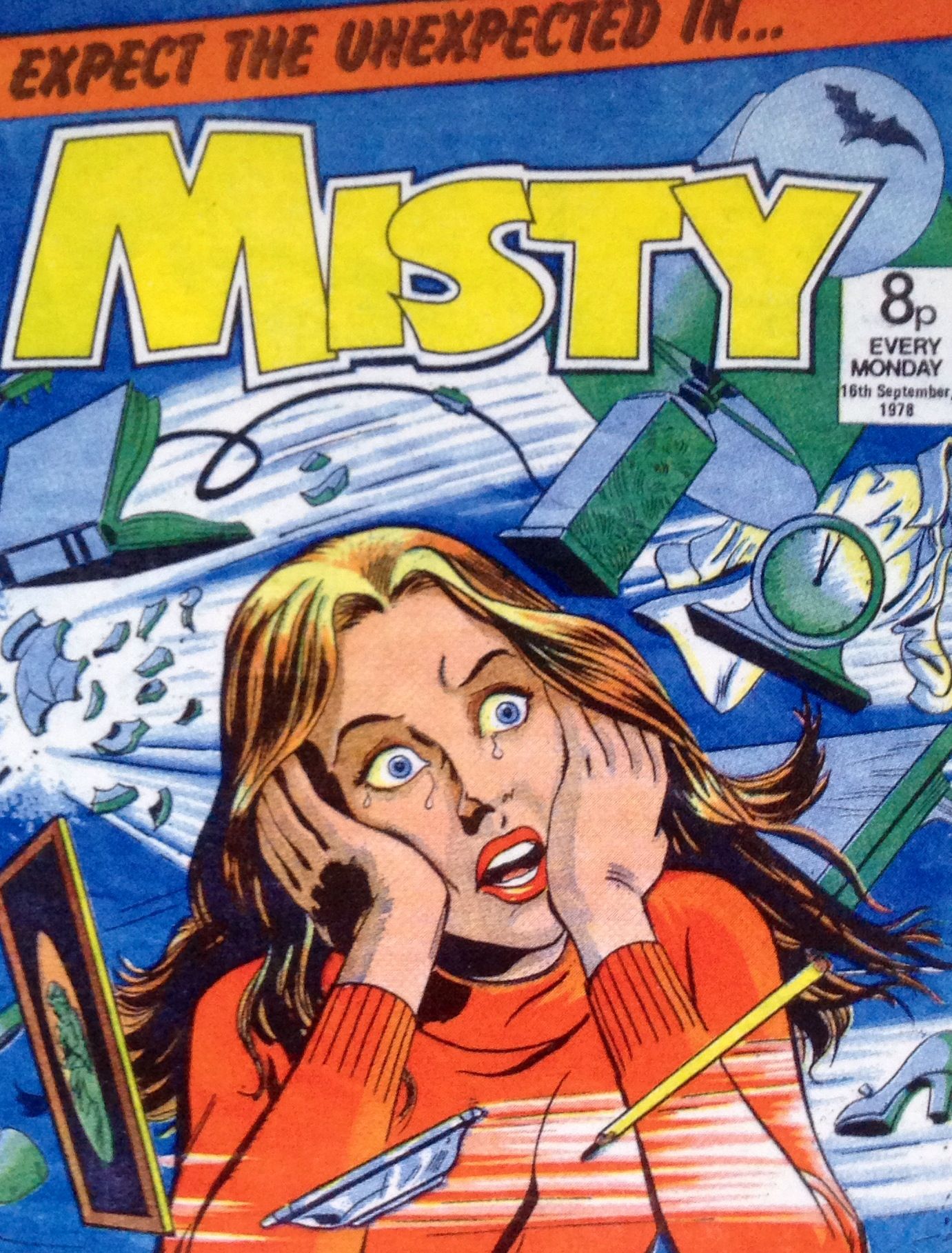

My study of children’s literature (which I also now teach at Bournemouth University) and my childhood memories of comics also combined to spark my most recent project. It’s a critical analysis of children’s horror comics, in particular two British girls’ comics: Spellbound (DC Thomson, 1976-78) and Misty (IPC, 1978-80). I’m fascinated by the presence of Gothic and horror in literature for children and young adults, which other critics such as Catherine Spooner, Chloe Buckley and Joseph Crawford are doing wonderful work on. My Misty project not only brought together my scholarly interests in sensationalist, Gothic and children’s literature (and comics!) but was also a very personal quest, as it partially grew out of a hunt for a half-remembered story that had haunted me for 33 years!

Gothic doesn’t seem to be easily categorized. Can we think of “Gothic” as a distinct generic category? In your view, how might Gothic be best described?

I think Gothic is hard to categorise because it is so wide-ranging. It takes on different forms at different times and in different media. Even if we just focus on Gothic literature, how can we find a definition that reconciles texts ranging from The Castle of Otranto (Walpole, 1764) to Twilight (Meyers, 2008)? They are miles apart in historical, philosophical, formal, generic and cultural terms. Gothic motifs have changed as the genre developed – Fred Botting identifies a turn from external to internal, and contemporary Gothic incorporates suburbia alongside the haunted castle. Its archetypes have also shifted – vampires are now sympathetic (Nina Auerbach), and zombies have moved from living slaves to cannibalistic corpses, and back again to an infected human. Critical approaches to Gothic are equally diverse, and many critics argue that Gothic is more than a genre, and may be better understood as a mode of writing or ur-form (David Punter), a poetic tradition (Anne Williams), a rhetoric (Robert Mighall), a discursive site (Robert Miles), or a habitus (Timothy Jones). Gothic is also full of contradictions – mobilising fear and attraction simultaneously and inviting us to read its texts as both shockingly transgressive (taboo acts and events) and rigidly conservative (as these acts are punished and order restored).

Gothic remains notoriously hard to define in all these models, and somewhat tautological. Critics like Baldick and Mighall have pointed out that most definitions really tell us more about what Gothic does than what it actually is. Critics such as Catherine Spooner, and Chloe Buckley also draw attention to overlooked Gothics that are celebratory or playful and which rely more on aesthetics than thematics. So Gothic becomes multiple and mutable, ranging from parody to pain, and can appear as affect, aesthetic, or practice. It’s hard to identify it without just listing common motifs, and the most successful definitions are those that are wide enough to work across different eras and media. Punter and Jerrold E. Hogle both offer definitions that involve archaic settings/spaces, supernatural or uncanny effects, haunting and secrets. Fear is of course a key element, although subjective, and so many critics focus on its textual presence rather than speculating about reader response, and try to identify the various forms that fear can take – most famously writer Ann Radcliffe separates it into terror (the unseen and speculative) and horror (the dramatic and repulsive).

For me, Gothic is a mode of creation (both literary and cultural) that draws on fear and is both disturbing and appealing. It is an affective and structural paradox: simultaneously giving us too much information (the supernatural, the unreal) and too little (the hidden, unseen, unknown). It is built on confrontations between opposing ideas, and contains an inner conflict characterised by ambivalence and uncertainty. It inverts, distorts, and obscures. It’s transgressive and seductive. Its common tropes (which are both aesthetic and affective) include temporal or spatial haunting, a reliance on hidden meaning (the crypt), and a sense of excess beyond control – and these are the three key components of my critical approach to comics. Within Gothic I recognize the distinctions that Radcliffe draws between terror (the threatening, obscured and unknown) and horror (the shocking, grotesque and obscene). Alongside these terms I also recognize horror as a cinematic and literary genre that privileges this second type of fear: a genre that shocks, disturbs, and confronts (see next question).

Is there a critical and conceptual distinction between the Gothic tradition and horror? Do you see these two functioning as a binary or do they possess a more closely knit relationship? Do you think that cultural distinctions have operated historically to canonize Gothic media as “high art,” while disparaging horror as cheap pop cultural ephemera?

I think there is a distinction between Gothic and horror. Radcliffe’s famous divide between terror/horror has been explored by numerous later critics and creators, from Devendra Varma (1957) to Stephen King (1981). In general there is agreement that (Gothic) terror is psychological and insidious while horror is violent and confrontational (see for example Gina Wisker; Dale Townshend), although the categories sometimes cross and blur.

The relationship and hierarchy between the two has been defined in numerous ways, and scholars’ positions seem to vary according to the medium and historical perspective that they use. In general I agree with critics like Gina Wisker, who argues that horror is ‘A branch of Gothic writing’ (p8), but by contrast, Xavier Aldana Reyes defines Gothic literature as ‘the beginnings of a wider crystallization of horror fiction’ (p15).

I also think medium has also played a part in validating and distinguishing the two. So within Gothic I follow the distinctions Radcliffe draws between horror and terror, but alongside these terms I also recognize horror as a cinematic and literary genre that privileges this second type of fear. When it comes to horror I certainly think there has been a value judgement made of the type you suggest – but alongside this I would stress that only one particular type of Gothic has been canonised (the serious, weighty, literary and often historical). If we take a more inclusive view of Gothic that includes fashions, parodies, cute Gothic and so on, many these forms have been equally sidelined and denigrated as ‘low’ pop culture, just like horror (see for example Catherine Spooner’s Post Millennial Gothic and Joseph Crawford’s The Twilight of the Gothic). So within Gothic itself there is a tension and a disparagement of certain types – particularly relating to the tastes of particular audiences such as young girls.

What authors and artists do you think have successfully adopted the Gothic aesthetic in their works? Are they historically contingent or is it more widespread that we might commonly think?

I want to pick that question apart a little first as I think a Gothic aesthetic is different from a Gothic thematic. Critics such as Stephen Farber (1972) and Spooner (2017) (writing nearly 50 years apart and across different media) have defined the Gothic aesthetic as based around elements such as exaggerated shadows/chiaroscuro; distorted proportions; skewed angles; asymmetry; baroque or intricate ornamentation; and motifs of age or decay. These can be used in combination with pleasurable or playful tales – for example the work of Tim Burton – which Spooner argues draws on aesthetic over affect, and which she defines as the ‘whimsical macabre’.

These aesthetic Gothics are often denigrated and viewed as lightweight, and there is a danger that when we analyse them we resort to simply listing motifs. I think Gothic has a complicated relationship between surface and depth; where aesthetic motifs can be linked with affective themes, but can also be decoupled. Purely aesthetic Gothics are often denigrated, like the works of Burton, which have been criticised as lightweight and superficial. Fred Botting puts forward a wider argument that this sort of ‘candygothic’ is a commercialised representation of the genre, with its bite removed. But Gothic has always been populist, and if we trace a path back through the Romance, sensationalist and Decadent genres (as critics such as Crawford have done) we can see that Gothic is in fact very widespread, varied, and popular in all its different forms.

Q Your work examines what we might describe as “unusual places” that Gothic can be found. Your most recent work examines the British “girl’s horror comic” Misty, which was published in the late-1970s until its cancellation in 1980. However, Misty may be somewhat alien to readers outside the field and British geography. Can you explain what it is about Misty that you find worthy of academic enquiry?

I like the conception of my work as looking for Gothic in unusual places! And that’s a great question, because if there’s one thing I like it’s talking about Misty! It’s a girls’ mystery comic that was published in the UK by IPC/Fleetway from 1978 to 1980. It ran for 101 weekly issues and it’s fondly remembered today by a generation of readers who were, quite frankly, scarred for life! It was an anthology comic that combined serials and single stories, and it definitely didn’t pull any punches. The serials were generally tales of personal growth where a heroine is thrown into the middle of a mystery, for example by receiving a magic item, or strange powers. (I’d argue that they act as clear metaphors for adolescence, as unwanted powers or transformations must be overcome before the heroine can be happy with her new identity or place.) But the single stories were even better – horrible cautionary tales in which bad heroines were punished in a number of very imaginative ways! They might be trapped permanently in magical items such as crystal balls, snow globes, music boxes, or weather houses; aged prematurely; ousted from their bodies; or transformed into something monstrous! They can also die in a number of horrible ways. The outcomes are often poetic justice (maybe looking back to EC Comics) – for example Cathy cons an old lady out of a moodstone ring which then sucks all the colour out of her life (‘Moodstone’, #1); a gossip columnist is crushed to death by the books of names and notes she has kept on her acquaintances (‘Sticks and Stones’, #16); clothes-thief Ann is turned into a fashion dummy (‘When the Lights go Out!’, #18); cruel siblings Vivien and Steve trap a mouse in a maze until it dies of exhaustion but are in turn locked in a maze by sentient apes (‘The Pet Shop’, #24); Sally awakens a real ghost while teasing her scared cousin (‘The Last Laugh’, #29); and so on. The Misty stories did not pull their punches and, while horrifying, there is also something blackly humorous about this sort of poetic justice that chimes with Horner and Zlosnik’s research into Gothic comedy.

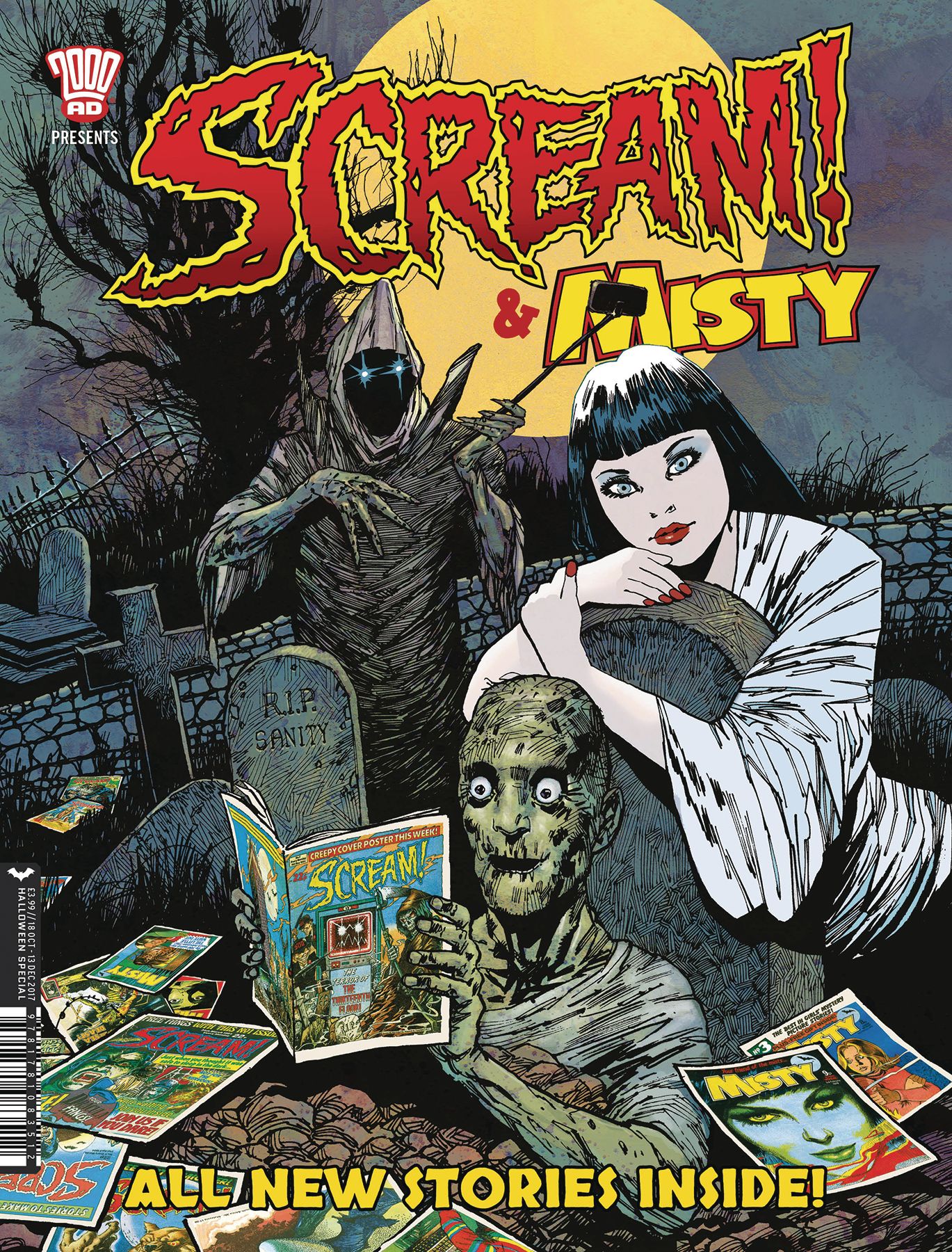

Misty is currently enjoying a series of reprints by Rebellion publishing. I think it has stood the test of time due to some great storytelling and fantastic artwork. It grew out of 2000AD creator Pat Mills’ idea for a girls’ horror comic inspired by the psychological horror of the day (such as Stephen King’s Carrie and Frank De Felitta’s Audrey Rose). It also owes a lot to DC Thomson’s Spellbound – a competitor title that ended shortly before Misty launched. But the comic that Misty became was much more than just horror rewrites. Its first editor Wilf Prigmore introduced the character of Misty herself, its fictional host and editor, who is beautifully drawn by Shirley Bellwood and acts as a sort of spirit guide to its readers. Its main editor Malcolm Shaw was a wonderful writer who shaped Misty around his own literary interests in science fiction and myth. The art came from a number of British and European artists who were absurdly talented – many of the Spanish artists who worked on Misty were also drawing for American horror titles such as Creepy and Eerie (Warren Publishing) at the same time, and they did not pull their punches. While most girls’ comics of the time had an average story episode length of 3 pages, Mills used his 2000AD approach on Misty and instead set the story length at 4 pages, allowing for plenty of dramatic visuals, large opening panels and splash pages. Its art editor Jack Cunningham took his cue from 2000AD’s Doug Church and marked up some of the scripts that went to artists to make each page as dramatic and exciting as possible – there are lots of large opening panels, borderless images and so on. I led a small research project that combined qualitative and quantitative analysis of layout and used the findings to reflect on current formalist comics theory – the findings were very illuminating!

I believe that pretty much everything is worthy of academic enquiry in some way, so I don’t want to make the case for Misty as an exceptional text – in many ways it is simply representative of the wider norms of the British comics industry at the time. So although it is a great example of Gothic storytelling structure and themes, I think Misty can also tell us a lot about the motivations and limitations of the British comics industry (see below), the aesthetics of comics storytelling, and (at a wider level) the intersections of genre and gender. My in-depth page analysis of Misty found that the vast majority of the pages were transgressive in some way, and I used these findings to reflect on established comics theory from scholars such as Thierry Groensteen and Neil Cohn. It led me to rethink many ideas about page layouts. The project also looks closely at how Gothic archetypes, tropes and themes are being reworked for a younger readership. As I mentioned above, the tastes of young female audiences have often been mocked and marginalised, and so there is a significant gap in scholarly material around these texts and their distribution that is only just starting to be addressed. Analysing the types of narratives that are offered to these readers tells us a lot about the cultural construction of gender and about the way in which genres like Gothic have been conceptualised and curated, excluding the tastes of particular demographics and privileging a narrow view of the genre.

So although it began as an attempt to track down a half-remembered story and explore my ideas about Gothic in comics from a new angle, my Misty project has grown far beyond that. I’ve done a ton of primary research (creator interviews, archival visits, analysis of scripts and publishers’ documents) alongside theoretical investigation of girls’ periodical publishing, fairy tale, children’s Gothic, Female Gothic, and British comics. I’ve produced a database of all the Misty stories, which includes all known writer and artist credits, story summaries, and their publication details, at www.juliaround.com/misty. It's a significant piece of work because the stories in British comics were not credited, and so I am indebted to experts such as David Roach and comics community forum discussions for much of the information I’ve gathered. I hope my database will enable further research and be a useful tool to help fans and scholars find those stories that they half remember or that are relevant to their work. I’ve also published some of the interviews I have done on the same website, and last year I published an open access article that explores the idea of Gothic for Girls by comparing Spellbound and Misty. My full critical book Gothic for Girls: Misty and British Comics is due to be published by UP Mississippi in Summer 2019. It’s easily been the most rewarding work I’ve done to date and I’m very excited about it!

Julia Round is a Principal Lecturer in the Faculty of Media and Communication at Bournemouth University, UK. She is one of the editors of Studies in Comics journal (Intellect Books) and a co-organiser of the annual International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference (IGNCC). Her first book was Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels (McFarland, 2014), followed by the edited collection Real Lives, Celebrity Stories (Bloomsbury, 2014). In 2015 she received the Inge Award for Comics Scholarship for her research, which focuses on Gothic, comics, and children’s literature. She has recently completed two AHRC-funded studies examining how digital transformations affect young people's reading. Her new book Misty and Gothic for Girls in British Comics (forthcoming from UP Mississippi, 2019) examines the presence of Gothic themes and aesthetics in children’s comics, and is accompanied by a searchable database of all the stories (with summaries, previously unknown creator credits, and origins), available at her website www.juliaround.com.