Cult Conversations: Interview with Shelley McMurdo (Part I)

/This week’s interview is with Shellie McMurdo, a PhD candidate at the University of Roehampton. Shellie is researching the found footage sub-genre through the lens of cultural trauma for her PhD thesis. In the following interview, Shellie and I discuss found footage horror cinema, and the promotional/ paratextual ballyhoo that surround these films as a way to enhance them as “real.” I strongly believe that Shellie is an upcoming ‘scholar-to-watch,’ and hugely enjoyed reading her many insights into found footage cinema—and more! I have certainly learned a great deal during our various exchanges; Shellie’s energy and passion for the subject is inspirational. She has also agreed to contribute a chapter on the Blair Witch film series for Horror Franchise Cinema, an anthology which I am co-editing with Dr. Mark McKenna for Routledge. The interview is published in two-parts.

— William Proctor

What is about the found footage horror genre that drew you to the topic? And how are you approaching it in terms of cultural trauma?

When I was studying Cult Film and Television at Brunel University, I started contemplating the idea of going on to do a PhD. I had a few false starts, where I went through a series of different topics as ideas for my PhD research. I thought at one point I was going to research torture horror, was very into rape revenge narratives for a while, and then I set my mind on examining the Slenderman phenomenon, which was back then in its infancy. In the end, I decided to study what I love, which is found footage horror.

I vividly remember watching The Blair Witch Project when I was around 15 years old, and being convinced it was real. I was unshakable in my certainty that I had just seen the last moments of three documentarians, and that their footage had somehow been found in the Burkittsville Woods and made into a film. You have to remember this was a good while before social media, and really, the internet back then was not the same internet we have now. I went on the Internet Movie Database, looked up the film, and saw that the cast members were listed as “missing – presumed dead” – My belief was solidified, they had been murdered and I had seen the footage of it! At school, the film was a hot topic of conversation, it wasn’t just me: we all believed it was real!

Of course, that belief was relatively short lived, but that film, and my belief in its veracity, really stayed with me, as it was so unlike anything else I had seen at that point. I had been heavily invested in horror films since my older brother had forced me to watch The Evil Dead when I was seven, but there was something about The Blair Witch Project that made it scarier to me than the other horror films I had watched. I think it was the narrative’s alignment to the real world, the idea that it was all real.

So, The Blair Witch Project definitely played a part in bringing me to this topic, and it sparked a passion for the found footage horror format. In the period between The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity – which it could be argued is the film that really brought found footage horror to a wider audience – in 2007, I would diligently seek out found footage horror films to watch, films like The Last Horror Movie, August Underground, and the superb Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon. I think it’s fair to say though, that in that period between 1999 and 2007, found footage horror was still relatively uncommon in the cinema. It was only after the success of Paranormal Activity that found footage horror production boomed, and it started to seem like every other film was in that style.

It was at that point that I started to feel quite protective of the found footage horror format. While it was true that there was a lot of absolute dross coming out in the wake of Paranormal Activity – the found footage “look” being cheap and easy to reproduce – there were some absolutely stunning films coming out too, like The Bay and The Sacrament among a whole host of others. These films would often get buried under the sheer volume of found footage horror being released, or dismissed as “just another found footage horror”.

There is definitely a desire that has driven my research in that I almost wanted to be a champion of found footage horror, and of new horror more widely. There are so many articles in journalism and within scholarly accounts which compare new horror to older “classic” horror and find new horror wanting, and that’s always bothered me. I see the horror genre’s canonisation process as a never ending cycle, so perhaps in twenty years time, we will look back at found footage horror, or say, torture porn, and see them as classic subgenres. But perhaps not!

Primarily, what has kept me engaged with looking at found footage horror is a mix of my own experience with the format throughout my formative years, and how the subgenre continues to fascinate me by constantly reinventing itself. You have the shaky handheld camera of The Blair Witch Project evolving into Go Pro found footage horror with the “A Ride in the Park” segment in V/H/S/2, social media horror in Unfriended, and the Snapchat based SickHouse. It is a format that not only is able to evolve but needs to constantly evolve because it presents itself as part of our reality, so it needs to stay up to date with the audience in their current cultural moment. That adaptability is definitely one of the strengths of the subgenre. Another aspect that has contributed to its staying power is just how broad the variety of stories are that the format can lend itself to, which is great for me, as it has essentially allowed me to have so many different strands in my research!

I’m approaching found footage horror from a cultural trauma perspective for a few reasons. My background, having studied History as my major at undergraduate level, gave me a keen awareness of the historical context different films were emerging from, and that has been a constant element in my work so far. I started looking at early German cinema for my BA in relation to the Weimar Republic, then in my MA I was relating the Hillbilly horror of American cinema in the 1970s to the Hoody Horrors emerging from Britain in the late 2000s. In a way, the research that I’m currently doing, is an amalgam of all the cultural trauma research I’ve done in my academic career up until this point.

A trauma studies perspective fits found footage horror particularly well, because to an even greater extent than other horror subgenres, found footage horror is so hyper aware of its audience, its formal aesthetics, and its context. Occasionally this means that found footage films tend to date themselves very quickly, because they are always involved in this reflexive awareness of the technology that is around at the time of their production. But on the flipside, because of this constant dialogue with its cultural context that found footage horror has, it works so well as a commentary on what cultural anxieties were present at the time.

One of the things that I admire most about the horror genre more widely is how it evolves and adapts, and it has always been an early adopter of new media forms, much more so than other genres. The cultural trauma position made sense to me because of how much the films that I’m looking at are a product of the time in which they were made. The intention of my current research is to examine found footage horror in reference to cultural events that have changed Western society. So, for example, the expansion of the internet and emergence of social media, 9/11, and reality television – each one of these things have given us a new or different version of the “real”, or what we perceive the “real” to be or look like. As each of these events have happened, there have been accompanying new cultural fears that have come with them. For example with social media, there was panic over cyberbullying and easier identity theft, with 9/11 you have this long lasting, low level of constant threat and fear of attack, and with reality television you start to get into what is real, what is mediated, and almost a performative version of reality.

The chapter that I am currently writing is looking at the relationship between documentary and found footage horror. If we take Cannibal Holocaust as the starting point of the genre, we can see that the documentary format is something the subgenre consistently returns to. What is interesting is that now you have documentary films – the example I’m using being Cropsey – that are real documentaries, about real events, but which are using the visual lexicon of found footage horror to tell their stories. The first time I watched that documentary, I had to look it up on the internet to check to see whether it was real or a found footage film, and that’s really interesting, especially in the era of “fake news” and mistrust of the media.

Moving on to the research I’m carrying out at the moment, the films that are the basis of my current chapter are The Sacrament and The Poughkeepsie Tapes, which are very different from each other while both functioning as fake found footage horror documentaries. With The Sacrament, the narrative is a reimagining of the Jonestown Massacre of 1978, but set in the modern day. It works to both address the trauma of Jonestown, an event that has only been memorialised publically in the last few years (despite being the largest loss of American life in history until the events of 9/11 in 2001), while resonating with current anxieties around religious extremism. And then The Poughkeepsie Tapes, which I spoke about in my most recent conference paper at the CATH post graduate conference at De Montfort University in June. The Poughkeepsie Tapes is a bit of a standout film in relation to the other films I’m looking at, in that its troubled release schedule has given it a unique quality the others don’t have. Basically, the film was originally scheduled for release in 2007/2008, and for some unknown reason it was pulled from the release schedule by MGM. Then, a few years later in 2014, it was released on a video on demand service, before it was quickly pulled from there after only a week. It wasn’t until late 2017, when Scream Factory gave it a DVD/BluRay release, that the film was available to a wider audience. So in the decade between the film’s original intended release date and its actual release, all kinds of myths and legends built up around it, with it being said that the footage in the film was real, and that it was somehow “too brutal” for even hardened horror audiences. Clips from the film would occasionally surface on compilation videos on Youtube, often under titles like “The scariest REAL footage”, and it remained a topic of conversation on horror forums and social media. This ephemerality of the film has just added to its mystique and the myths around it.

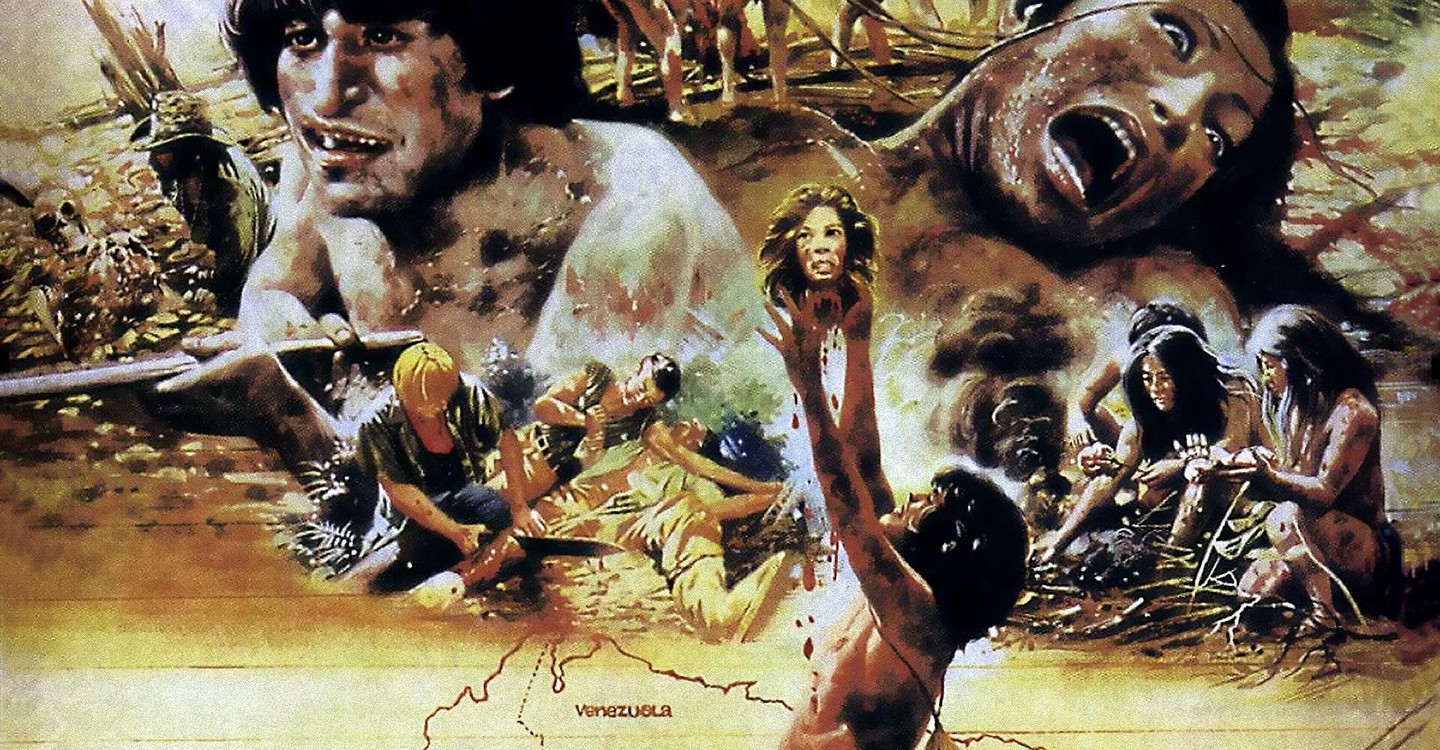

The recounting of your lived experience with The Blair Witch Project is fascinating and I believe that this kind of response is what the filmmakers had in mind in promotional terms. There is usually a lot of ‘ballyhoo’ attached to at least some films in the found footage genre. We might describe this as a method of signalling authenticity through paratexts—of reality rather than the codes and conventions of realism. I am reminded of Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust— often cited as the first found footage film as you point out—and the way in which the discourse surrounding the film during the so-called Video Nasties moral campaign in the early 1980s became part and parcel of marketing the film as ‘illicit,’ ‘lurid,’ and ‘dangerous’ (the 2011 Shameless blu-ray proudly announces that the film remains ‘the most controversial film ever made, with Eli Roth emphatically declaring that ‘it is one of the most brutal, relentless, violent, realistic films ever made.’) Deodato was arrested on obscenity charges with the belief that he had made a legitimate ‘snuff’ film. Complicating matters further, the actors had signed a contract not to appear in other media for a year in order to construct Cannibal Holocaust as a legitimate documentary, and Deodato even had to produce the actors to show that they were indeed alive, before the court case was dropped. In your research, have you come across other examples of such ballyhoo and promotional gimmickry in relation to found footage films? You have mentioned The Blair Witch Project.

You are absolutely right, paratexts play such a huge part in a large amount of found footage horror films, whether this is an attempt to try to build some hype for a film, to encourage viewers to engage pre- and post- viewing, or a genuine attempt at trying to pass the film off as being real.

Cloverfield for example, had two websites, which were set up long before the film was released, in addition to Myspace profiles for the main characters. One of the websites www.1.18.08.com gave the user clues as to what the Cloverfield monster’s origins were, whereas the second website www.whencloverfieldhit.com encouraged users to upload their own videos addressing where they were when the attack in the film happened. To me, the second website is the most interesting because of the level of interaction and ‘call to play’ - to borrow Craig Hight’s term – it is encouraging. But the Cloverfield websites definitely fall into the category of trying to get viewers involved, rather than encouraging them to believe the film is real, which - given the content of the film - would be a bit of a stretch!

Another good example is The Upper Footage, which drummed up interest by using Youtube to release several clips long before the film’s release. The most notorious of these was uploaded in 2010, entitled NYC Socialite Overdose, which showed people at a party with pixelated faces supposedly snorting cocaine. Youtube subsequently removed the video – I think it may have been re-uploaded since - but confusion arose from several media outlets as to the veracity of the footage, and gossip websites began to speculate over the identity of celebrities that may have been involved. Eventually the director, Justin Cole, released a statement in 2013 on Dreadcentral.com where he denied the footage was real. Most interestingly, Cole made a caveat in that interview that he was admitting the fictitious status of the footage with ‘much hesitation’, which to me implies that he genuinely wanted to pass it off as being real but perhaps was moved to debunk the footage because of the gossip sites and possible backlash. We won’t ever know for sure if he would have made a sustained attempt at passing the film off as real but perhaps The Upper Footage comes close to replicating the confusion both Cannibal Holocaust and The Blair Witch Project caused, although causing less serious issues than Cannibal Holocaust did for Deodato!

What makes The Poughkeepsie Tapes so intriguing to me, is the confusion that has grown around the film’s truth status. What is even more intriguing is how this confusion is really kind of an accident due to the film not being released for a decade. A great deal of the online articles on the film also have this fixation on the idea that the film was banned, which it never was. There’s a recurrent argument in these articles that the reason behind the “banning” of the film is that it featured either real footage or footage so realistic and brutal that it was just ‘too much’ for cinema goers. This is key to The Poughkeepie Tapes appeal, that it is somehow a limit experience for the viewer, and these kind of statements are definitely replicated in online responses to the film on social media, some of which urge potential viewers not to watch the film because it is so upsetting/brutal/life changing, and then you get the extreme end of that where audience members are perpetuating the idea that the footage in the film is real. I must note though that it is unclear if they truly believe that or are playing into the idea of that possibility. The hype around The Poughkeepsie Tapes is reminiscent of how Cannibal Holocaust is positioned as this ‘illicit’ or potentially dangerous film.

It is however a remarkably brutal film and definitely stands out for that reason within found footage horror more generally. The eponymous tapes in the film also have that look that we have become familiar with through beheading videos, or through gore websites such as Rotten.com, a kind of “snuff authenticity”, and the film being released when it was, after the emergence of online real death videos - such as 3 Guys, 1 Hammer and 1 Lunatic, 1 Icepick – allows us to draw that parallel, although we have to remember that those two particular videos weren’t around during the film’s production.

Shellie McMundro is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Roehampton, where she is examining found footage horror cinema and its connection to cultural trauma. She has presented her work, on found footage horror and additionally on new media horror, period drama, and horror gaming, at a variety of conferences. Shellie has a forthcoming article in the European Journal of American Culture, which ties together research on American Horror Story, The True Crime fandom and school shooters. Her research interests are extreme horror, new media, trauma theory, online fandoms, and transmedial texts.